Big Hill

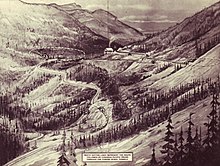

The Big Hill on the Canadian Pacific Railway main line in British Columbia, Canada, was the most difficult piece of railway track on the Canadian Pacific Railway's route.[1] It was situated in the rugged Canadian Rockies west of the Continental Divide and Kicking Horse Pass. Even though the Big Hill was replaced by the Spiral Tunnels in 1909, the area has long been a challenge to the operation of trains and remains so to this day.

The essential problem was that the railway had to ascend 1,070 feet (330 m) along a distance of 10 miles (16 km) from Field at 4,267 feet (1,301 m) climbing to the top of the Continental Divide at 5,340 feet (1,630 m).[2] The narrow valleys and high mountains limited the space where the railway could stretch out and limit the grade (hence the later decisions to bore extra mileage under the mountains and lower the grades).

Construction

To complete the Pacific railway as quickly as possible, a decision was made to delay blasting a lengthy 1,400-foot (430 m) tunnel through Mount Stephen and instead build a temporary 8-mile (13 km) line over it. Instead of the desired 2.2% grade (116 feet to the mile) a steep 4.5% (some sources say 4.4%) grade was built in 1884.[3] This was one of the steepest adhesion railway lines anywhere. It descended from Wapta Lake to the base of Mount Stephen, along the Kicking Horse River to a point just west of Field, then rose again to meet the original route.

Seen as a temporary solution, this grade was twice the percentage normally allowed for a downhill track. The first construction train to go down the pass ran away off the hill to land in the Kicking Horse River, killing three.[4] The CPR soon added three safety switches (runaways) on the way down to protect against runaway trains. The switches led to short spurs with a sharp reverse upgrade and they were kept in the uphill position until the operator was satisfied that the train descending the grade towards him was not out of control. Speed was restricted to 8 miles per hour (13 km/h) for passenger trains and 6 miles per hour (9.7 km/h) for freight, and elaborate brake testing was required of trains prior to descending the hill. Nevertheless, disasters occurred with dismaying frequency.

Field was created as a work camp solely to accommodate the CPR's need for additional locomotives to be added to trains about to tackle the Big Hill. Here a stone roundhouse with turntable was built at what was first known simply as Third Siding. In December 1884 the CPR renamed it Field after C.W. Field, a Chicago businessman who, the company hoped, might invest in the region after he had visited on a special train they had provided for him.

At that time, standard steam locomotives were 4-4-0s, capable enough for the prairies and elsewhere, but of little use on the Big Hill. Baldwin Locomotive Works was called upon to build two 2-8-0s for use as Field Hill pusher engines in 1884. At the time they were the most powerful locomotives built. Two more followed in June 1886. The CPR began building its own 2-8-0s in August 1887, and over the years hundreds more were built or bought.

Spiral Tunnels

The Big Hill "temporary" line remained the main line for 25 years until the spiral tunnels were opened on September 1, 1909.

The improvement project was started in 1906, under the supervision of John Edward Schwitzer, the senior engineer of CPR's western lines. The first proposal had been to extend the length of the climb, and thus reduce the gradient, by bypassing the town of Field at a higher level, on the south side of the Kicking Horse river valley. This idea had quickly been abandoned because of the severe risk of avalanches and landslips on the valley side. Also under consideration was the extension of the route in a horseshoe loop northwards, using both sides of the valley of the Yoho River to increase the distance, but again the valley sides were found to be prone to avalanches. It was the experience of severe disruption and delay caused by avalanches on other parts of the line (such as at the Rogers Pass station, which was destroyed by an avalanche in 1899) that persuaded Schwitzer that digging spiral tunnels was the only practical but expensive way forward.

The route decided upon called for two tunnels driven in three-quarter circles into the valley walls. The higher tunnel, "number one", is about 1,000 yards (0.91 km) in length and runs under Cathedral Mountain, to the south of the original track. When the new line emerges from this tunnel it has doubled back, running beneath itself and 50 feet (15 m) lower. It then descends the valley side in almost the opposite direction to its previous course before crossing the Kicking Horse River and entering Mount Ogden to the north. This lower tunnel, "number two", is a few yards shorter than "number one" and the descent is again about 50 feet. From the exit of this tunnel the line continues down the valley in the original direction, towards Field. The constructions and extra track effectively double the length of the climb and reduce the ruling gradient to 2.2%. The new distance between Field and Wapta Lake, where the track levels out, is 11+1⁄2 miles (18.5 km).[5]

The contract was awarded to the Vancouver engineering firm of MacDonnell, Gzowski and Company and work started in 1907. The labour force amounted to about 1000 and the cost was about $1.5 million.

Regardless of the opening of the spiral tunnels, Field Hill remained a significant challenge and it was necessary to retain the powerful locomotives at Field locomotive depot.[5] Even after the introduction of modern locomotives with dynamic braking and continuous pneumatic brakes, accidents were not eliminated.[6] There were 64 derailments between Calgary and Field between 2004 and 2019.[7]

On February 4, 2019, two of the three locomotives and 99 cars of westbound Canadian Pacific grain train 301 derailed at Mile 130.6, just outside of the western portal of Upper Spiral Tunnel. The three crew members were killed in the accident.[7]

See also

References

- ^ "Construction of the CPR". Old Time Trains.

- ^ Lake Louise & Yoho (Map) (5 ed.). Cochrane, Alberta: Gem Trek Publishing. ISBN 1-895526-14-0.

- ^ Buck (1997: 23)

- ^ Graeme Pole, The Spiral Tunnels and the Big Hill: A Canadian Railway Adventure. Canmore: Altitude Publishing, 2000, p. 50

- ^ a b Soole, G. H (1937). "Field and the Big Hill". Factors in railway and steamship operation. Montreal: Canadian Pacific Railway. General Publicity Department. OCLC 264115110. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ "Runaway/Derailment Canadian Pacific Railway Train No. 353-946 Laggan Subdivision Field, British Columbia 02 December 1997: Other Occurrences" (PDF). Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 10 December 1999. p. 21. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ a b Feb 06, CBC News · Posted; February 6, 2019 10:35 AM MT | Last Updated. "Fatal train derailment: A closer look at what happened that tragic day | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Berton, Pierre (1971). The Last Spike. Toronto/Montreal: McCelland and Stewart Ltd. ISBN 0-14-011763-6.

- Buck, George H (1997). From Summit to Sea. Calgary: Fifth House. ISBN 1-895618-94-0.

- Carter, Charles Frederick (May 1910). "The Passing of "The Big Hill": Eight Miles of Steep Canadian Pacific Track That No Longer Require Four Big Engines to Haul One Train". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XX: 13039–13035. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- Lamb, W. Kaye (1977). History of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Collier MacMillan Canada Ltd. ISBN 0-02-567660-1.

- Lavalee, Omer (1974). Van Horne's Road. Railfare Enterprises Ltd. ISBN 978-0-919130-22-7.

- Pole, Graeme (1999). The Spiral Tunnels and the Big Hill. Canmore: Altitude Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55153-908-9.

- Turner, Robert D. (1987). West of the Great Divide. Victoria BC: Sono Nis Press. ISBN 0-919203-51-5.

- Yates, Floyd (1985). Canadian Pacific's Big Hill. Calgary, Alberta: BRMNA. ISBN 978-0-919487-14-7.