Collapse of Smile

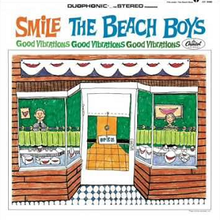

The Beach Boys' failure to complete the album Smile is often reported as a pivotal episode marking the professional decline of the band and its leader Brian Wilson.[1][2] Some of the difficulties and pressures surrounding the album's making included its cumbersome editing process, concerns over its potential reception, the Wilson family's resentment of Brian's new social circle, Carl Wilson's arrest for draft evasion, the band's attempt to terminate their contract with Capitol Records, their heavy marijuana consumption, and Brian's escalating mental health issues and creative dissatisfaction.

The original Smile sessions lasted from August 1966 to May 1967. Brian produced and completed most of the album's backing tracks by December 1966. When the Beach Boys returned from a month-long tour of Europe, they were confused by the new music and the new coterie of interlopers that surrounded him. After missing a January 1967 deadline, the album's release date was repeatedly postponed as he tinkered with the recordings, experimenting with different takes and mixes, unable or unwilling to supply a completed version of the album. Meanwhile, he suffered from paranoid delusions, such as believing that the album track "Fire" caused a nearby building to burn down.

At the end of February 1967, the Beach Boys filed suit against Capitol for $255,000 in unpaid royalties. Within weeks, Parks distanced himself from the group due to various disputes, and Wilson consequently lost track of how to complete the album. It is sometimes suggested that Mike Love was responsible for the project's collapse. Love regards such claims as hyperbole and said that his vocal opposition to Wilson's drug suppliers was what spurred the accusation that he, as well as other members of the band and Wilson's family, sabotaged the project.

Wilson concluded that Smile was too esoteric for the public and decided to record simpler music instead. A stopgap album, Smiley Smile, was recorded throughout June and July, and after a settlement was reached with Capitol, released in September. Smile was left incomplete while Wilson gradually abdicated his leadership of the Beach Boys and retreated from the public eye. Over the ensuing decades, he became disabled by his mental health problems to fluctuating degrees.[3][2] In 2004, he finished a version of Smile as a solo artist, Brian Wilson Presents Smile. A compilation and box set dedicated to the Beach Boys' original recordings, The Smile Sessions, followed in 2011.

Background

After the Wilsons' father Murry was fired as the Beach Boys' manager in April 1964, Brian began a process of expanding his social circle to include a mix of worldly-minded friends, musicians, mystics, and business advisers from the developing Los Angeles "hip" scene. He also took an increasing interest in recreational drugs (particularly marijuana, LSD, and Desbutal).[4] While on a December 23 flight from Los Angeles to Houston, Brian suffered a panic attack.[5] The 22-year-old Wilson had already skipped several concert tours by then, but the airplane episode proved devastating to his psyche,[6] and to focus his efforts on writing and recording, he indefinitely resigned from live performances.[5][7] The Beach Boys continued to tour without Wilson, who was replaced by Bruce Johnston on the road, and Wilson's personal relationship with the band became more distant.[8]

In mid 1965, multi-instrumentalist Van Dyke Parks was introduced to Wilson by mutual friends David Crosby and Terry Melcher.[9] About a year later, Wilson asked Parks to collaborate as lyricist for the Beach Boys' upcoming album project, soon titled Smile, to which Parks agreed.[10] Parks introduced Wilson to Derek Taylor, former press officer for the Beatles, who then became the Beach Boys' publicist.[11] Meanwhile, Wilson became acquainted with former MGM Records agent David Anderle thanks to a mutual friend, singer Danny Hutton (later of Three Dog Night). Anderle, who was nicknamed "the mayor of hip", acted as a conduit between Wilson and the "hip".[12] Parks said that, eventually, "it wasn't just Brian and me in a room; it was Brian and me ... and all kinds of self-interested people pulling him in various directions."[13]

Additional writers were brought in as witnesses to Wilson's Columbia, Gold Star, and Western recording sessions, who also accompanied him outside the studio. Among the crowd: Richard Goldstein from the Village Voice, Jules Siegel from The Saturday Evening Post, and Paul Williams, the 18-year-old founder and editor of Crawdaddy![14] As Wilson made more connections, "[his] circle of friends enlarged to encompass a whole new crowd," biographer Steven Gaines writes. "Some of these people were 'drainers,' [but others] were talented and industrious".[15] Other notable friends of Brian in this era included Michael Vosse, Anderle's assistant, and Paul Jay Robbins, a journalist from the underground press.[16] David Oppenheim, who briefly visited Wilson's home to film a segment for the documentary Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, later described the scene as "a strange, insulated household, insulated from the world by money ... A playpen of irresponsible people."[17]

Commenting on the reliability of figures such as Anderle, Siegel, and Vosse, journalist Nick Kent wrote that their claims are oftentimes "so lavish [that] one can be forgiven, if only momentarily, for believing that Brian Wilson had, at that time orbited out to the furthermost reaches of the celestial stratosphere for the duration of this starcrossed project."[18] Gaines acknowledged that the "events surrounding the album differed so much according to each person's point of view, that no one can be certain."[19]

Growing band tensions

The Beach Boys' album Pet Sounds, issued on May 16, 1966, was massively influential upon its release, containing lush and sophisticated orchestral arrangements that raised the band's prestige as rock innovators.[20] Capitol Records continued promoting the Beach Boys as a surfing group, much to the band's disdain.[21] Wilson requested that Taylor establish a new image for the band as fashionable counterculture icons, and so a promotional campaign with the tagline "Brian Wilson is a genius" was created and coordinated by Taylor.[22][nb 1] Wilson told Melody Maker: "Our new album will be better than Pet Sounds. It will be as much an improvement over Sounds as that was over [our 1965 album] Summer Days."[24]

Throughout the summer of 1966, Wilson concentrated on finishing the group's forthcoming single, "Good Vibrations".[25] According to various reports, both the Pet Sounds and "Good Vibrations" recording sessions were fraught with tension between the group members.[26] Wilson's bandmates resented that he was singled out as a "genius",[27] while he believed that they were worried about him separating from the group.[28] He recalled that the band "liked Pet Sounds but they said it was too arty",[29] and that they eventually "gave in [and] let me have my little stint".[28] In 1976, he said that some group members were frustrated with the lengthy recording devoted to "Good Vibrations", but declined to name who specifically.[30] Derek Taylor could not recall hearing "a single disparaging word [about Brian from the other Beach Boys] in all that time. Maybe a few jokes about his eccentricities, but always basically affectionate."[31] Anderle said the first problems with Brian's bandmates were when they voiced concerns about losing "what the Beach Boys are" by going too "far out" beyond a "simple dumb thing", and that they did not want to change their "physical image" (i.e. their striped shirts and white pants stage uniforms).[32]

Released on October 10, 1966, "Good Vibrations" was the Beach Boys' third US number-one hit, reaching the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in December, and became their first number one in Britain.[33] That month, the record was their first single certified gold by the RIAA.[34] The Beach Boys were soon voted the number-one band in the world in an annual readers' poll conducted by NME, ahead of the Beatles, the Walker Brothers, the Rolling Stones, and the Four Tops.[35] Biographer David Leaf wrote that the success of "Good Vibrations" "bought Brian some time [and] shut up everybody who said that Brian's new ways wouldn't sell...his inability to quickly follow up 'Good Vibrations' [was what] became a snowballing problem."[36]

By December 1966, Wilson had completed much of the Smile backing tracks. When the Beach Boys returned from a month-long tour of Europe, they were confused by the new music he had recorded and the new coterie of interlopers that surrounded him.[2] Gaines wrote that David Anderle now appeared to them as the leader of "a whole group of strangers [that] had infiltrated and taken over the Beach Boys". Anderle had been encouraging Wilson to leave the group, and he was "sure they saw me as somebody ... who was fueling Brian's weirdness. And I stand guilty on those counts."[37]

Drug use

As Wilson prepared for the writing and recording of Smile, he purchased about $2,000 worth of marijuana and hashish.[38] He told journalist Timothy White in 1976: "a lot of the stuff [Smile recordings] was what I call little 'segments' of songs, and it was a period when I was getting stoned, and so we never really got an album; we never finished anything! ... We were too fucking high, you know, to complete the stuff. We were stoned! You know, stoned on hash 'n' shit!"[39] Carl recalled: "To get that album out, someone would have needed willingness and perseverance to corral all of us. Everybody was so loaded on pot and hash all of the time that it's no wonder the project didn't get done."[40]

Gaines writes that one of Brian's "best friends" at the time was an assistant at the William Morris Agency named Loren Schwartz (later Lorren Daro), whose knowledge of "trendy [books] widely read by college kids ... seemed mystical and terribly important to [Brian]."[41] In early 1965, Schwartz introduced Wilson to LSD, recounting the dosage as 125 micrograms of "pure Owsley", and that "he had the full-on ego death. It was a beautiful thing."[42] To the dismay of Brian's wife Marilyn, Schwartz became a daily visitor to their Laurel Way home.[43] Additionally, only a week after his first LSD trip, Wilson began experiencing persistent auditory hallucinations.[44] The group was aware of Brian's LSD use, according to Al Jardine, who "wanted to be as far away from that as possible! Because I didn't want to know about it—I wanted the innocence!"[45] He said that "everybody was high but me" and compared the experience to being "trapped in an insane asylum."[46]

Michael Vosse described Brian's use of drugs as "the biggest red herring in [his] story I've heard so far," and rebuked the accusation that Brian was "some kind of nut". In reference to a story about Brian installing a tent into his living room to hold meetings, Vosse said "we were all excited about it, [and] anybody who thinks this was like Brian being wacko and everybody [else disapproving] is wrong." Danny Hutton disputed that the drugs "got in the way at all" and said that they actually helped Brian "work longer hours." Parks said: "Don't let the marijuana confuse the issue here. If you look at the amount of work that was done in the amount of time it took to almost finish it, it's amazing. A very athletic situation, very focused."[47] He also expressed feeling uncomfortable with the drug scene,[48][49] and said that he only partook in the drugs at Brian's insistence.[50]

Wilson's instability and paranoia

Following the recording session for the album track "Fire" on November 28, 1966, Brian became irrationally concerned that the music had been responsible for starting several fires in the neighborhood of the studio. Brian claimed for many years that he then burned and destroyed the Smile tapes,[51] but that was not the case, although he did abandon the "Fire" piece for good. Parks deliberately stayed away from the session—during which Brian encouraged the musicians to wear toy firemen hats—and that he later described Brian's behavior as "regressive",[52] something which band mates also observed during and after this session.[53] By the beginning of 1967, Brian's behavior became increasingly erratic, and his use of drugs escalated. For instance, taking advice from his astrologer who told him to beware of "hostile vibrations", Wilson holed up in his bed for days smoking cannabis and eating candy bars.[54] Other stories involve Brian cancelling a $3,000 string session because of the room's inexplicably negative atmosphere,[55] delusions of Phil Spector taunting him with coded messages hidden in the newly-released John Frankenheimer film Seconds,[56] and another delusion where he was convinced that a portrait of himself, painted by Anderle, had literally captured his soul.[38] Anderle believed that his relationship with Brian crumbled immediately after the portrait episode.[38]

While such actions were a concern for some of his friends, Brian usually maintained his diligence and a professional demeanor for most of the recording sessions.[57] His paranoia also sometimes had a rational basis. Music historian Domenic Priore noted his high position in the music industry and an instance where the master tapes for "Good Vibrations" had been stolen by an unknown party for three days.[58] Brian believed that his father and Phil Spector hired private investigators to follow him, and in turn, Brian hired his own private investigators to follow them. Although Spector was not actually tracking Brian, it was thought that Murry was.[59] Rumors were also abound that the Smile tapes were being leaked from their Los Angeles studios, and the 1967 Sagittarius single "My World Fell Down" indicated to Brian that others were copying his work on Smile.[60][nb 2] Parks explained that being "invited to a session was a big deal in those days, and certainly to know what Brian's process was would be something that everybody desired at that time, because he was such an opinion-maker and he was inventing new formats, new ways of working."[13]

Brian degraded us, made us lay down for hours and make barnyard noises, demoralized us, freaked out ... we hated him then because we didn't really know what was happening to him.

Mike Love reflected: "When we were younger, no one really knew what was wrong with Brian. Nobody knew about mental illness. We just had no clue about that as kids, as cousins and brothers, growing up ..."[63] Bruce Johnston recalled listening to tracks from Smile, "and I don't feel any joy, I feel uncomfortable, I can hear Brian disintegrating. The music was cool but it's always tinged with the reality of making it."[62] Commenting on how Brian's emotional state affected his work schedule, David Anderle said that "Brian [could not] go into a session with something happening in the back of his head ... [if something causes] him to worry and grieve, he's not going to be able to cut [a record] ... he would try almost heroically to get something done, but he couldn't."[64]

Sidetracks, recording tedium, and Capitol lawsuit

During the making of Smile, Wilson planned many different multimedia side-projects, such as a sound effects collage, a comedy album, and a "health food" album.[38] Capitol did not support some of these ideas, which led to the Beach Boys' desire to form their own label, Brother Records. According to Gaines, Love was "the most receptive" to the proposal, wanting the Beach Boys to have more creative control over their work, and supported Wilson's decision to employ his newfound "best friend" David Anderle as the head of the label, even though it was against the wishes of band manager Nick Grillo.[65] Plans for the label began in August 1966.[66] In a press release, Anderle stated that Brother Records was to give "entirely new concepts to the recording industry, and to give the Beach Boys total creative and promotional control over their product."[67] On January 3, 1967 Carl Wilson refused to be drafted for military service, leading to indictment and criminal prosecution which he challenged as a conscientious objector.[68] He was arrested by the FBI in early May, and it would take several years in the courts before the matter would be resolved.[69]

Once Brian missed a January 15 album deadline, he concentrated mostly on the projected singles; first "Heroes and Villains", then "Vega-Tables", and then "Heroes and Villains" again.[70] Throughout the first half of 1967, the album's release date was repeatedly postponed as Brian tinkered with the recordings, experimenting with different takes and mixes, unable or unwilling to supply a completed version of the album.[3] Anderle remembered how it "was just impossible to keep up with that man. He was setting up blocks of studio time, would get uptight if he couldn't get a studio ... four in the morning he'd be sitting around and he'd get an idea and he'd want to be able to go in the next morning, like at seven or eight and record. Couldn't do that, obviously, because you can't operate that way."[71] When asked if Wilson was afraid of "putting something out that he couldn't top," Anderle answered: "No way! During that period, there was no way ... he really had a sense of it being a beginning. I don't think Brian ever had a sense of anything being the pinnacle."[72]

The reason Smile did not see release in 1967 had more to do with back room business ... than anything else.

A February 1967 lawsuit seeking $255,000 (equivalent to $2.33 million in 2023) was launched against Capitol over neglected royalty payments. Within the lawsuit, there was also an attempt to terminate the band's contract with Capitol prior to its November 1969 expiry.[74] Even if Smile was completed during this juncture, it may not have seen an immediate release due to the lawsuit.[75] Paul Williams saw that "Ironically, the independence that forming Brother Records was supposed to bring to Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys was the very thing that knocked Smile–and the Beach Boys–out of the water. David Anderle's initial idea in the formation of Brother Records was sound, but the time it takes to put this type of thing through the courts was not conducive to the production race that was important during this period of radical change in pop."[61] The Capitol lawsuit was eventually settled, the band receiving their $200,000 in exchange for Brother Records to distribute through Capitol Records, along with a guarantee that the band produce at least one million dollars profit.[76]

Eventually, the number of possible variations for song edits became too overwhelming for Wilson.[77][nb 3] Danny Hutton compared the challenge to hearing "a commercial ten times, and all of a sudden you start humming it, and you don't even know if you like it or not, because you've heard it so many times you can't even judge ... He lost that ability of the 'freshness' to know which part should go where."[80] Smile Sessions co-producer Mark Linett argued that Wilson could not have finished the album simply because his ambitions were unfeasible with pre-digital technology: "In 1966, [assembling pieces] meant physically cutting pieces of tape and sticking them back together—which is how all editing was done in those days—but it was a very time-consuming and labor-intensive process, and most importantly made it very hard to experiment with the infinite number of possible ways you could assemble this puzzle."[79] His colleague Alan Boyd shared the same view, stating that the tape editing "would have been probably an unbearably arduous, difficult and tedious task".[77] Wilson said: "Time can be spent in the studio to the point where you get so next to it, you don't know where you are with it, you decide to just chuck it for a while."[78]

Artistic and commercial concerns

Contemporary music climate

It was also a thing of, "What if it didn't turn out to be great, what if it had totally flopped?" That would have completely destroyed him [Brian]. We would have lost him forever in terms of having any communication with him.

Another reason Smile was not released, Wilson said, was because "people wouldn't understand where my head was at, at that time."[47] In later years, he described the album as "too advanced" to have been released in 1967.[77][nb 4] Hutton supported that, after a certain point, Wilson doubted whether the album would still be received as a culturally relevant work among record-buyers and the contemporary rock audience.[80] Richard Goldstein, who met Wilson in 1967, said that "he came across as deeply insecure about his creative instincts, terrified that the songs he was working on were too arty to sell."[81]

Smile drew from what most rock stars of the time considered to be antiquated pop culture touchstones, like doo-wop, barbershop, ragtime, exotica, pre-rock and roll pop, and cowboy films.[82] Music journalist Erik Davis wrote of the album's disconnect to the hippie subculture, noting that "Smile had banjos, not sitars".[83] In 1968, Wilson stated that he shelved the album because he did not have a "commercial feeling" for its songs and surmised, "Maybe some people like to hang on to certain songs as their own little songs that they've written, almost for themselves. You know, what they've written is nice for them ... but a lot of people just don't like it."[84]

In the months coinciding with Smile's delays, several revolutionary rock albums were issued to an audience that was similarly growing in sophistication, while Wilson's image was reduced to that of an "eccentric" figure. From February to May 1967, this included Jefferson Airplane's Surrealistic Pillow, the Velvet Underground's The Velvet Underground and Nico, the Jimi Hendrix Experience's Are You Experienced, and the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[85][nb 5] Music historian Luis Sanchez writes that as time passed, the hype for Smile turned into "expectation", then "doubt", and finally, "bemusement".[86]

Disagreements

We got very paranoid about the possibility of losing our public. ... Drugs played a great role in our evolution but as a result we were frightened that people would no longer understand us, musically.

The financial interests of the band and their families was also a major pressure for Wilson.[38][nb 6] David Anderle and Michael Vosse recalled that the Beach Boys' vocal sessions for Smile were tense between Brian, Parks, and the other group members,[76] and that it caused Brian "tremendous paranoia" knowing every studio visit would lead to an argument.[88] Danny Hutton could not remember Brian having doubts about the music until afterward,[47] and reflected that the touring members were also worried about how they would be able to perform the songs live.[80] Durrie Parks, then-wife of Van Dyke, said that there were recording sessions in which "people wouldn't participate" and "meetings where it was discussed that this wasn't going well."[47] Vosse recalled: "The vibe was getting worse and worse. Brian was trying to complete one of the most ambitious projects in pop music. But the people close to him were rolling their eyes and saying, 'Are you sure?' And that really got to him."[89] Anderle believed that the Beach Boys had "no way to relate to what Brian was putting down" before Sgt. Pepper proved that such ambitious combinations of disparate music elements and surreal lyricism could be successful.[2]

In reference to such claims, band archivist Alan Boyd commented that no evidence of "drama and angst" appears on the recordings he heard while compiling The Smile Sessions.[90] A reviewer for the compilation similarly reported that no "Let It Be style sniping" is audible on any of the session highlight tracks.[77] Having attended some of the sessions circa January 1967, NME journalist Tracy Thomas wrote that Brian's "dedication to perfection does not always endear him to his fellow Beach Boys, nor their wives, nor their next door neighbours, with whom they were to have dinner ... But when the finished product is 'Good Vibrations' or Pet Sounds or Smile they hold back their complaints."[91] Anderle said that tensions between Parks and Wilson flared after February. The songwriters "started clashing" because Brian thought Parks' "lyric was too sophisticated, and in some areas Brian's music was not sophisticated enough [for Van Dyke]."[71] Ultimately, he stated, "a great reason why Smile wasn't finished" was because of "resistance in the studio."[92]

Race against the Beatles

Derek Taylor commented that Brian was preoccupied with "a mad possessive battle" against the Rolling Stones and "particularly" the Beatles, and that he "didn't want me to like any other artist but himself. I could never stand bands competing over me. It was never a problem with the Byrds, mind. But Brian..."[93] He added that it was "strange too, because the fact that Pet Sounds hadn't sold at all well didn't even bother him. He was only interested in these 'Who Is The Best?' heats. ... Criticism was hell for him because you can only say it's great one more time and he'd never leave you in peace."[94][nb 7] Anderle supported that "Brian always felt that ... the Beatles were number two [with Derek] ... He had a very strong feeling about that."[64]

Throughout early 1967, the music industry and pop fans were aware that the Beatles were working on a significant new work as their follow-up to Revolver, with the band having been ensconced in their London studios since the previous November.[96] Wilson told a Rolling Stone interviewer in 1987 that when he started Smile, he was "trying to beat" the Beatles; when asked whether Smile would have topped his rivals' subsequent release, Wilson replied: "No. It wouldn't have come close. Sgt. Pepper would have kicked our ass."[97] According to historian Darren Reid: "In Wilson's mind, the first album to market [in 1967] would be the one to claim victory, it would be the record which would set the standard against which all other albums released after that time would have to be judged."[98] Reportedly, his first exposure to the Beatles' February 1967 single "Strawberry Fields Forever" affected him. He heard the song while driving with Michael Vosse under the influence of barbiturates. Vosse said that as Wilson pulled over to listen, "He just shook his head and said, 'They did it already—what I wanted to do with Smile. Maybe it's too late.' I started laughing my head off, and he started laughing his head off ... But the moment he said it, he sounded very serious."[47][99] Responding to a fan's question on his website in 2014, Wilson denied that hearing the song had "weakened" him.[100]

After finishing Sgt. Pepper in early April 1967, Paul McCartney visited the US to reunite with his actress girlfriend Jane Asher and to learn of developments in the San Francisco music scene.[101] While staying with Taylor in Los Angeles, McCartney attended a Beach Boys recording session and played him the Sgt. Pepper song "She's Leaving Home", and according to Beatles biographer Ian MacDonald, advised Wilson not to delay in his response to Revolver.[102] In a January 1968 interview, Wilson stated of the McCartney episode that "it was a little uptight and we really didn't seem to hit it off. It didn't really flow. ... It didn't really go too good."[103] He became aware of rumors alleging that Taylor had possibly played some of the Smile tapes for the Beatles. According to Parks, Wilson felt "very sad" and began "question[ing] the loyalties of the people who were working for him".[104][nb 8]

"Heroes and Villains" single

In July 1967, "Heroes and Villains" was released after months of delays. Al Jardine called the final mix a "pale facsimile" of Brian's original vision: "He purposefully under-produced the song ... It was lost because Brian wanted it to be lost. He was no longer interested in pursuing number one."[107] Terry Melcher recalled that, before the single was released, Wilson personally delivered an exclusive acetate of the record to radio station KHJ by limousine.[38] As he excitedly offered the vinyl record for radio play, the DJ refused, citing program directing protocols, which Melcher said "just about killed [Brian]".[108] "Heroes and Villains" ultimately peaked at only number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100, and was met with confusion by the general public. Anderle said that whatever new fans the group had brought with Pet Sounds were "immediately lost with the [single]."[109] This included Jimi Hendrix, who negatively described the song as a "psychedelic barbershop quartet" to the NME.[82] Wilson's emotional state plummeted further, as the band's future manager Jack Rieley wrote for an online Q&A in 1996:

Brian blirted [sic] it out one evening at [his home], and later spoke about it several times in agonizing detail. He had expected that [the single] would be greeted by Capitol as the work which put the Beach Boys on a creative par with the Beatles. All the adoration and promotional backup Capitol was giving the Beatles would also flow to his music because of ["Heroes and Villains"], he thought. And the public? It would greet [the song] with the same level of overwhelming enthusiasm that the Beatles got with record after record. As it was, Capitol execs were divided about [the song]. Some loved it but others castigated the track, longing instead for still more surfing/cars songs. The public bought the record in respectable but surely not wowy zowy numbers. For Brian, this was the ultimate failure. His surfing/car songs were the ones they loved the most. His musical growth, unlike that of Messrs. Lennon and McCartney, did not translate into commercial ascendancy or public glory.[110]

In Wilson's own words, he became "fucked up" and "jealous" of the Beatles and Phil Spector,[111] once dismissing Smile as an imitation of Spector's work without "getting anywhere near him".[112] Writing in 1981, sociomusicologist Simon Frith identified Wilson's subsequent withdrawal, along with Spector's self-imposed retirement in 1966, as the catalysts for the "rock/pop split that has afflicted American music ever since". Frith added that, while the influence of both these producers was evident in 1967 hit songs by the Electric Prunes, the Turtles, Strawberry Alarm Clock, Tommy James and the Shondells, and the 5th Dimension, the most enduring and successful American pop act was the Monkees, which had been created as "an obvious imitation of the Beatles".[96]

Cancellation

In March 1967, Parks left the project, but returned the next month.[113] On April 14, 1967,[114][88] he left the project for good in the wake of signing a record deal with Warner Bros. Records so he could work on his debut album Song Cycle.[54] He said: "I walked away from the situation as soon as I realized that I was causing friction between him and his other group members, and I didn't want to be the person to do that."[115] Jules Siegel said that Parks was "tired of being constantly dominated by Brian."[59] Parks was depended upon by Wilson whenever issues came up in the studio, and when he left, the end result was that Wilson lost track of how the album's fragmented music should be assembled.[116]

Wilson discussed breaking up the Beach Boys "on many occasions," according to Anderle, "But it was easier, I think to get rid of the outsiders like myself than it was to break up the brothers. You can't break up brothers."[109] Siegel was exiled from Wilson's social circle on the grounds that his girlfriend had been disrupting Wilson's work through ESP.[117] Anderle said that at the time "I couldn't put my finger onto why Smile was now starting to nose dive, other than the fact that I still felt at that point that the central thing was Van Dyke's severing of the relationship."[118] He left of his own accord weeks later, after it became apparent that Brian felt he had to prioritize the wishes of the group and his family above all else.[38] The last time Brian was visited by Anderle to discuss business matters, he refused to leave his bedroom.[38] Danny Hutton remained in the circle and recalled "the vibe was still great" several months later.[119]

In the last two April 1967 issues of the weekly British journal Disc and Music Echo, Derek Taylor reported that it was uncertain when the Beach Boys' next album or single would be ready.[120][121] On May 6, he announced in the publication that the Smile tapes had been destroyed by Wilson and would not see release. He wrote: "What, then? I don't know. The Beach Boys don't know. Brian Wilson, God grant him peace of mind...he doesn't know."[122] According to author Christian Matijas-Mecca, it is unlikely that Brian was aware of Taylor's announcement, as he proceeded to record the Smile track "Love to Say Dada" only days later.[85] Taylor later described the scene at the time as "all hell breaking loose. It was tapes being lost, ideas being junked — Brian thinking 'I'm no good' then 'I'm too good' — and then 'I can't sing! I can't get those voices anymore'".[123] Desperate for a new product from the group, the group's British distributor EMI released "Then I Kissed Her" as a single without the band's approval.[124]

Wilson was left psychologically scarred by the making of Smile[125] and requested Capitol to keep the album unreleased: "We didn't tell them for how long. We told them 'For a while.'"[77][nb 9] He said the group "nearly broke up for good" when he asked that "Surf's Up" be shelved.[127] Taylor terminated his employment with the group to focus his attention on organizing the Monterey Pop Festival, an event the Beach Boys declined to headline at the last minute. They received significant criticism for their withdrawal,[107] as Gaines writes, the decision "had a snowballing effect" that came to represent "a damning admission that [the Beach Boys] were washed up".[128]

Smiley Smile and Wild Honey

all of a sudden I decided not to try any more, and not try and do such great things, such big musical things. And we had so much fun. ... I didn't have any paranoia feelings [when we made Smiley Smile].

The Beach Boys were still under pressure and a contractual obligation to record and present an album to Capitol.[130] Carl remembered: "Brian just said, 'I can't do this. We're going to make a homespun version of [the album] instead. We're just going to take it easy. I'll get in the pool and sing. Or let's go in the gym and do our parts.' That was Smiley Smile."[40][nb 10] By July, the group's dispute with Capitol was resolved, and it was agreed that Smile would not be the band's next album.[73] Released in September, Smiley Smile was met with mixed reviews and the group's worst sales yet, becoming the first in a seven-year string of under-performing Beach Boys albums.[134] Some of the original Smile tracks continued to trickle out in later releases, often as filler songs to offset Brian's unwillingness to contribute.[135] The band was still expecting to complete and release the album as late as 1973 before it became clear that only Brian could comprehend the innumerable fragments that had been recorded.[136] In the meantime, he gradually ceded production and songwriting duties to the rest of the group and self-medicated with the excessive consumption of food, alcohol, and drugs.[137]

In October 1967, Cheetah magazine published "Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!", a memoir written by Jules Siegel.[138][139] The article credited Smile's collapse to "an obsessive cycle of creation and destruction that threatened not only his career and his fortune but also his marriage, his friendships, his relationships with the Beach Boys and, some of his closest friends worried, his mind".[140] Carl blamed the article and "a lot of that stuff that went around before" with "really turn[ing Brian] off."[38] He also remembered that Brian was concerned about critics who thought "the band, and Brian in particular, [sounded] like choirboys, [while Brian felt we] should get more into a white R&B bag." [citation needed] Johnston said that "we wanted to be a band again. The whole [Smile] thing had wiped everyone out, and we wanted to play together again."[107]

Within three months after the release of Smiley Smile, the Beach Boys recorded and released a new album, Wild Honey, which was heavily influenced by soul music. Carl described it as "music for Brian to cool out by. He was still very spaced."[141] In December 1967, Mike Love told a British journalist: "Sure people were baffled and mystified by Smiley Smile but it was a matter of progression. We had this feeling that we were going too far, losing touch I guess, and this new one brings us back more into reality ... Brian has been re-thinking our recording program and in any case we all have a much greater say nowadays in what we turn out in the studio."[142]

Mike Love

It has been suggested that Don't fuck with the formula be merged into this section. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2019. |

Mike Love is sometimes cited as the reason for the album's collapse. According to Love, he did not have an issue with "crazy stupid sounds" or following Brian's odd requests, but he still desired "to make a commercially successful pop record, so I might have complained about some of the lyrics on Smile."[143][nb 11] Carl supported that—with regards to the Smile material—Love's only misgiving was Parks' lyrics.[146] Brian denied that Love's opposition to the lyrics made him shelve the album. In a 1998 deposition related to the memoir Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story, he stated, "No. There weren't as many lyrics as there was just—see, Smile wasn't a lyrical thing."[147] On a later occasion, he said that one of the reasons Smile was never released was because "Mike didn't like it". In the same interview, he stated that "they knew it was good music, but they didn't think it was right for them."[47][nb 12] Although Brian could have sung all the necessary parts, he said, "I still needed them to do it. I needed that Beach Boy blend. They didn't think they were right for it, but I knew they were right for it."[47] Anderle described Carl as "diplomatic", Dennis as supportive,[47] and Love as concerned about "fuck[ing] with the formula".[149][nb 13]

A December 6, 1966 session for "Cabin Essence" was the scene of an argument between Van Dyke Parks and Mike Love after the latter requested that Parks explain the meaning of the lyrics he was to sing. Parks later said the event marked the point in which he started distancing himself from the project.[151] Love was skeptical of Parks' lyrics, and worried that they would not be appreciated and understood by the group's fans. The obtuseness of the lyrics led him to adopt the term "acid alliteration" when describing them.[152][88] He argued that if the words of "Good Vibrations" did not have "anything to connect to people intellectually or emotionally, then it would have been a brilliant piece of music, but perhaps not gone to No 1."[153] In a 1968 article for Crawdaddy!, Anderle characterized Love as "Brian's opposite", remembering that Wilson would "stomp right out" of the room due to the frustration of "trying to relate to Mike". He said that Brian repeatedly accused Love of being a "businessman" and "soulless", however, it was "very untrue, Mike is a very soulful person ... [but he's] the only one really who is aware of business, for the group ... Mike was the easiest one for me to relate to, outside of Brian ... because Mike understood what I was trying to do on a business level".[109]

Later, Love commented that he was held responsible for the collapse only when the accounts of "Anderle and the other hipsters" were used as sources in writings about the Beach Boys. He said that their role as Wilson's drug suppliers was understated so that they would avoid accountability for Wilson's subsequent mental decline and struggles with substance addiction, thus shifting the blame onto himself. A 1971 Rolling Stone article by Tom Nolan inspired a 1978 biography by David Leaf, titled The Beach Boys and the California Myth, which concluded that "If Brian sought refuge within drugs, in reaction to all the pressure, then everybody must share the blame—the record company, the family, the Beach Boys, and Brian's entourage."[154] Love noted that the book included anonymously-quoted attacks toward Marilyn Wilson, who "had called Brian's new friends 'users' because she saw how they exploited Brian for their own careers while bringing the drugs into her house."[155] He took to the issue of Wilson's "hagiographers and sycophants" in his 2016 autobiography:

I was even more outspoken [than Marilyn] about the drugs and my contempt for these same opportunists, so I took the brunt of their scorn. ... for Brian's awestruck biographers (Leaf was only the first), the morality tale of the tormented genius who was undone by his own family—putting commerce ahead of art—that tale was too great to resist. Anderle crystallized this theme, in the 1971 Rolling Stone article, by claiming that I told Brian, "Don't fuck with the formula." By the time Leaf's book was published, Anderle told Leaf that my quote "was taken slightly out of context." It was still used. ... Whatever reservations we had about Smile—and yes, I had them—we put them aside and did everything we could to help Brian realize his dream.[156]

In the revised 1985 edition of The Beach Boys and the California Myth, Leaf wrote that he "no longer indict[s] the world of 'being bad to Brian,' when it’s apparent that Brian has been hardest on himself."[157] Parks accused Love of historical revisionism,[158] believing that the hostility Love held toward Wilson and Smile was "the deciding factor" in the album's postponement.[159] After being told of Love's self-proclaimed love for the material, Parks reportedly stated laughingly, "I'm just incredulous. I can't believe that he's an enthusiast. I wouldn't condemn him if it took him some time to come to that conclusion."[160] In response to press material surrounding the Beach Boys' 50th anniversary reunion and Smile Sessions compilation, Parks released a statement on his website that read: "Certainly I did walk away from Smile. ... I comment only to combat any doubt that Mike Love delayed the release of Smile by 40 years purely out of a mislaid jealousy. Smile was an obviously good work."[158]

"Don't fuck with the formula"

The statement "don't fuck with the formula" originates from a 1971 Rolling Stone magazine article written by freelancer Tom Nolan titled "The Beach Boys: A California Saga".[161] Nolan's article unusually devoted minimal attention to the group's music, and instead focused on the band's internal dynamics and history, particularly around the period when the band fell out of step with the counterculture of the 1960s.[162] The relevant text pertaining to the "formula" quote is as follows:

Mike Love was the tough one for David. Mike really befriended David: He wanted his aid in going one direction while David was trying to take it the opposite way. Mike kept saying, "You're so good, you know so much, you're so realistic, you can do all this for us—why not do it this way," and David would say, "Because Brian wants it that way." "Gotta be this way." David really holds Mike Love responsible for the collapse. Mike wanted the bread, "and don't fuck with the formula."[38]

Anderle later stated that the line "was taken slightly out of context" and that Love was more concerned with the "bottom line" than the "artistic" side of business.[163][nb 14] Love denied ever telling Wilson "don't fuck with the formula", adding that the Beach Boys "have no formula. In 1967 alone, the year I supposedly made that comment, we recorded Wild Honey, an R&B album that was entirely different from anything we'd ever done, and I cowrote ten songs and sang three leads."[166] In a 1998 deposition related to the memoir Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story, Wilson testified that Love had never spoken the line to him.[147] Pet Sounds lyricist Tony Asher did not recall hearing the remark and could not verify whether it was actually spoken. He said that, "it seems very much like Mike. And to tell the truth, I think he had a point," arguing that Pet Sounds "was not much of a success" and that its music "was [probably] not what Beach Boys fans were expecting."[167][nb 15]

Over the ensuing years, "don't fuck with the formula" was repeated in myriad books, articles, websites, and blogs.[161] The remark is usually invoked to signal the conflicts that arose between Wilson and Love when the former began subverting the "formula" that brought the Beach Boys their initial success: songs with lyrics that embraced girls, cars, and surfing.[169] According to journalist David Hepworth, the style of Nolan's 1971 article was unprecedented in the field of music writing, and the "story within was destined to become a classic piece from that brief interlude when pop writing collided with New Journalism ... It combined admiration for the group's achievements with distaste for their strange, inner world in a way that hadn't been done before".[162]

In 2017, Rolling Stone included the cousins' discord as one of "Music's 30 Fiercest Feuds and Beefs". Contributor Jordan Runtagh wrote that when Wilson "sought to move the band beyond their fun-in-the-sun persona. Love found the new musical daring pretentious, and feared alienating the fans originally won over by their carefree surfing image."[170] In 2014, fans reacted negatively to the announcement that Wilson would be recording a duets album, comparing it to a "cash-in". A Facebook post attributed to Wilson responded to the feedback: "In my life in music, I’ve been told too many times not to fuck with the formula, but as an artist it’s my job to do that."[171]

Brian Wilson Presents Smile

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2019) |

The Smile Sessions

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2019) |

References

Notes

- ^ Taylor is widely recognized as instrumental in the album's success with the British due to his longstanding connections with the Beatles and other industry figures in the UK.[23]

- ^ These episodes were part of the reasons why he later constructed his own personal recording studio.[60][61]

- ^ Carl Wilson: "Brian ran into all kinds of problems on Smile. He just couldn't find the right direction to finish it."[78] According to Bruce Johnston: "It was almost like he was climbing Mount Everest, and he was getting more boulders hanging on his back and snow coming down on him while he was trying to finish, and finally he just didn't finish it."[79]

- ^ Biographer Peter Ames Carlin contested Wilson's statement, saying that Wilson invented this story as a generic line to tell journalists in 2004, and that "[being] ahead of his time is exactly what they were looking for."[77]

- ^ In the weeks following Smiley Smile's release, "three distinct, but equally important albums" also came out: Cream's Disraeli Gears, the Who's The Who Sell Out, and the Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed.[85]

- ^ An unnamed observer told Gaines: "... knowing that everyone in that group was married, and had children and a house. I think he [Brian] felt like more of a benefactor than an artist."[37]

- ^ One of Brian's "thoroughly insistent psychologically arm-twisting tactic[s to] test my devotion to his cause", as Taylor called it, was to play "a new song [of his] and immediately start ... making statements like 'Better than the Stones, yeah?' Then he'd put on [a song like] 'Paperback Writer', and say ... 'Is that really any good?' and I'd have to say very deliberately, 'Yes Brian, it is very good.' He was never satisfied though. Never."[95]

- ^ Parks remembered the rumor being that two members of the Beatles had visited Armen Steiner's studio to listen to unmixed Smile master tapes, and believed that this meant Sgt. Pepper's was influenced by Smile.[105] The tapes were temporarily housed there, however, only after the Beach Boys enacted the Capitol lawsuit in February 1967.[106]

- ^ On May 20, Disc and Music Echo wrote that "[c]ontrary to some reports, plans for the 'Heroes and Villains' the group's scheduled new single, have not been completely scrapped. Roger Easterby of the Howes office, who was with the boys throughout their British tour, said: 'When the boys return to the States [in June] they will spend a complete month in the studios completing 'Heroes and Villains' and also working on a new LP.'"[126]

- ^ Capitol A&R director Karl Engemann began circulating a memo, dated July 25, 1967,[131] in which Smiley Smile was referred to as a "cartoon" stopgap for Smile. The memo also discussed conversations between him and Wilson pertaining to the release of a 10-track Smile album, which would not have included the songs "Heroes and Villains" or "Vegetables".[132][133] Biographer Andrew Doe speculated that the memo may have reflected Brian "being his usual agreeable self and telling people what they wanted to hear ... or a simple misunderstanding."[131]

- ^ In 1975, Love voiced appreciation of the musical form and content of "Surf's Up" from Smile, which he believed went beyond what is normally expected of commercial pop music,[144] and in the same 1992 article where he refers to some of the Pet Sounds lyrics as "nauseating", he calls Parks a "very gifted musician", saying: "He's great. He's one of the nicest persons in the world. And I tell him, 'Hey, I thought your lyrics, Van Dyke, were brilliant, except who the fuck knows what you're talking about!' That's exactly how I talk to him (laughs). And he and I joke about it."[145]

- ^ He said, in 2011, that Love was "disgusted" with the album because it did not have songs normally expected from the Beach Boys.[148]

- ^ In a 1998 court deposition, Brian testified that Love had never spoken the line to him.[92] In 2004, he also said that Love, Jardine, and Dennis "hated the Smile tapes".[150]

- ^ Whenever Wilson composed for the Beach Boys, he typically relied on others to provide lyrics to his music. At this stage, he usually worked with Love,[164] whose assertive persona provided the youthful swagger that contrasted against Wilson's explorations in romanticism and sensitivity.[165] Occasionally, Wilson would work with lyricists outside of his band's circle. Love recalls that he "was not happy" when this would occur—except in the case of Roger Christian, whose special knowledge of motor jargon he says benefited the group's car songs.[145]

- ^ Peter Ames Carlin writes in his 2006 biography that Asher still remembered "hearing Brian complain about Mike instructing him, in no uncertain terms: 'Don't fuck with the formula.'"[168]

Citations

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d Staton, Scott (September 22, 2005). "A Lost Pop Symphony". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ a b Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 118.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, p. 92, wordly-minded mix; Gaines 1986, pp. 155, 163, Murry, fascination with hip

- ^ a b Sanchez 2014, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 142.

- ^ Hoskyns 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Henderson 2010, pp. 38, 40–41.

- ^ Dombal, Ryan. "5–10–15–20: Van Dyke Parks The veteran songwriter and arranger on the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, and more". Pitchfork.

- ^ Gaines 1986, pp. 155–156, 158.

- ^ a b Priore 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, p. 94.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 158.

- ^ Kent 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 171.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 264.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 162.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 72.

- ^ "Comments by Carl Wilson". The Pet Sounds Sessions (Booklet). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records. 1997.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Sanchez 2014, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 152.

- ^ "Brian Wilson". Melody Maker. October 8, 1966. p. 7.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Kent 2009, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 110.

- ^ a b Cromelin, Richard (October 1976). "Surf's Up! Brian Wilson Comes Back From Lunch". Creem.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 114.

- ^ Felton, David (November 4, 1976). "The Healing of Brother Brian: The Rolling Stone Interview With the Beach Boys". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 262.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 224.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 255.

- ^ a b Gaines 1986, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nolan, Tom (October 28, 1971). "The Beach Boys: A California Saga". Rolling Stone (94).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Love 2016, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Himes, Geoffrey (September 1983). "The Beach Boys High Times and Ebb Tides Carl Wilson Recalls 20 Years With and Without Brian". Musician (59).

- ^ Gaines 1986, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Carlin 2006, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 135–136.

- ^ "Brian Wilson – A Powerful Interview". Ability. 2006. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Boyd, Alan (Director) (1998). Endless Harmony: The Beach Boys Story (Documentary).

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Carlin 2006, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Leaf, David (Director) (2004). Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of Smile (Documentary).

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Kozlowski, Carl (February 21, 2013). "The man behind the music". Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 111.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (June 16, 1993). "AUDIO: Van Dyke Parks (1993)". Rock's Backpages Audio.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 302.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 172.

- ^ Holdship, Bill (December 2004). "The Beach Boys: Is Mike Love Evil?". Mojo.

- ^ a b Kent 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Kent 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Siegel, Jules (October 17, 1967). "Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!". Cheetah. No. 1.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Alpert, Neal. "That Music Was Actually Created". Gadfly. Gadfly Online. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Priore 1995, p. 266.

- ^ a b Crawdaddy, Volumes 10–23. Crawdaddy Publishing Company, Incorporated. 1967. p. 84.

- ^ a b Priore 2005, p. 116.

- ^ a b Holdship, Bill (August 1993). Mojo.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Fine, Jason (June 21, 2012). "The Beach Boys' Last Wave". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ a b Priore 1995, p. 233.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 164.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 60.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Buchanan, Michael (January 2, 2012). "January 3, 1967, Beach Boy Carl Wilson Becomes a Draft Dodger – Today in Crime History". Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "The Beach Boys". Music Favorites. Vol. 1, no. 2. 1976.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 111.

- ^ a b Priore 1995, p. 230.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 258.

- ^ a b Dillon 2012, p. 134.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 170, 178, 243.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 256.

- ^ a b Vosse, Michael (April 14, 1969). "Our Exagmination Round His Factification For Incamination of Work in Progress: Michael Vosse Talks About Smile". Fusion. 8.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d e f Masley, Ed (October 28, 2011). "Nearly 45 years later, Beach Boys' 'Smile' complete". Arizona: AZ Central. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Leo, Malcolm (Director) (1985). The Beach Boys: An American Band (Documentary).

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b "The Beach Boys - SMiLE Sessions Webisode #9 - Chaos & Complexity" (Video). YouTube. The Beach Boys. November 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Three Dog Night's Danny Hutton on Brian Wilson Part 9". YouTube (Interview: Video). Interviewed by Danny Hutton. Prism Films. June 18, 2012.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (April 26, 2015). "I got high with the Beach Boys: "If I survive this I promise never to do drugs again"". Salon.

- ^ a b Petridis, Alexis (October 27, 2011). "The Beach Boys: The Smile Sessions – review". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Davis, Erik (November 9, 1990). "Look! Listen! Vibrate! SMILE! The Apollonian Shimmer of the Beach Boys". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 78.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Griffiths, David (December 21, 1968). "Dennis Wilson: 'I Live With 17 Girls'". Record Mirror.

- ^ a b c Hoskyns 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Carlin 2006, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "The Beach Boys - SMiLE Sessions Webisode #7 - Love of Harmony". YouTube. The Beach Boys. November 18, 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Tracy (January 28, 1967). "Beach Boy a Day: Brian—Loved or Loathed Genius". NME. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b Love 2016.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 263, "mad possessive battle"; Kent 2009, p. 32, "didn't want me to ..."

- ^ Priore 1995, pp. 263, 267.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 263.

- ^ a b Frith, Simon (1981). "1967: The Year It All Came Together". The History of Rock. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Pond, Steve (November 5 – December 10, 1987). "Brian Wilson". Rolling Stone. p. 176.

- ^ Reid, Darren R. (2013). "Deconstructing America: The Beach Boys, Brian Wilson, and the Making of SMiLE". Open Access History and American Studies.

- ^ Kiehl, Stephen (September 26, 2004). "Lost and Found Sounds (page 2)". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Brian Answer's Fans' Questions in Live Q&A". January 29, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. pp. 169–70. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian (1998). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7126-6697-8.

- ^ Highwater, Jamake (1968). Rock and Other Four Letter Words: Music of the Electric Generation. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-552-04334-6.

- ^ Priore 2005, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Zolten, Jerry (2009). "The Beatles as Recording Artists". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Leaf, David (1990). Smiley Smile/Wild Honey (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Priore 1995, p. 235.

- ^ Rieley, Jack (October 18, 1996). "Jack Rieley's comments & Surf's Up".

- ^ Love 2016, p. 107.

- ^ Kent 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 119.

- ^ Claster, Bob (February 13, 1984). "A Visit With Van Dyke Parks". Bob Claster's Funny Stuff. bobclaster.com. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Kent 2009, pp. 38, 42.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 231.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Taylor, Derek (April 22, 1967). Disc and Music Echo.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Taylor, Derek (April 29, 1967). Disc and Music Echo.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Carlin 2006, p. 120.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 267.

- ^ "Beach Boys Think This Too Dated". NME. May 7, 1967. p. 10.

- ^ Himes, Geoffrey (October 1, 2004). "Brian Wilson Remembers How To Smile". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ Disc and Music Echo. May 20, 1967.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Priore 2005, p. 134.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 179.

- ^ Highwater, Jamake (1968). Rock and other four letter words; music of the electric generation. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0552043342.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 124.

- ^ a b Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 82.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 195.

- ^ Priore 1995, p. 160.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 200, release date; Lambert 2016, p. 216, underwhelming reception; Carlin 2006, p. 124, worst sales; Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 80, seven-year string

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 148.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. xxii, 113.

- ^ Carlin 2006, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, pp. 99, 102.

- ^ Lambert 2016, p. 219.

- ^ Leaf 1985, p. 125.

- ^ P.G. (February 1968). "'Personal Promotion is the thing' say Beach Boys". Beat Instrumental.

- ^ Hedegaard, Erik (February 17, 2016). "The Ballad of Mike Love". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Cohen, Scott (January 1975). "Beach Boys: Mike Love, Carl Wilson Hang Ten On Surfin', Cruisin' And Harmonies". Circus Raves. p. 27.

- ^ a b "Good Vibrations? The Beach Boys' Mike Love gets his turn". Goldmine. September 18, 1992.

- ^ Was, Don (Director) (1995). Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn't Made for These Times (Documentary film).

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Love 2016, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Wilson, John (October 21, 2011). "Brian Wilson interview". Tintin; Brian Wilson interview. bbc.co.uk. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 154.

- ^ Schneider, Robert (October 21, 2004). "Smiles Away". Westword. Archived from the original on November 7, 2004.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Carlin 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 114.

- ^ Pinnock, Tom (June 8, 2012). "The Making of Good Vibrations". Uncut.

- ^ Love 2016, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 162.

- ^ Love 2016, pp. 162, 166.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, p. 25.

- ^ a b Parks, Van Dyke. "'Twas Brillig: Van Dyke Parks answers the general inquisition (viz "author" Mike Eder et al) on the Beach Boys' reunion and Smile". Bananastan. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ "Letters". MOJO Magazine. February 2005.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (June 24, 2011). "The astonishing genius of Brian Wilson". The Guardian. London: The Guardian. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Love 2016, p. 164.

- ^ a b Hepworth 2016, p. 223.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 164; Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. xx–xxi, "bottom line"

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Schinder 2007, p. 108.

- ^ Love 2016, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Dontsurf, Charlie, ed. (March 2007). "Pet Sounds: Words by Tony Asher" (PDF). In My Room. p. 1.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ Runtagh, Jordan (September 15, 2017). "Music's 30 Fiercest Feuds and Beefs: Brian Wilson vs. Mike Love". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (June 12, 2014). "Brian Wilson fans furious at Frank Ocean and Lana Del Rey collaborations". The Guardian.

Bibliography

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas, eds. (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-653-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink1=ignored (|editor-link1=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editorlink3=ignored (|editor-link3=suggested) (help) - Carlin, Peter Ames (July 25, 2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-320-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dillon, Mark (2012). Fifty Sides of the Beach Boys: The Songs That Tell Their Story. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-77041-071-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306806476.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Henderson, Richard (2010). Van Dyke Parks' Song Cycle. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-2917-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hepworth, David (2016). Never a Dull Moment: 1971 The Year That Rock Exploded. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-62779-400-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoskyns, Barney (2009). Waiting for the Sun: A Rock 'n' Roll History of Los Angeles. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-943-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kent, Nick (2009). "The Last Beach Movie Revisited: The Life of Brian Wilson". The Dark Stuff: Selected Writings on Rock Music. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780786730742.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lambert, Philip, ed. (2016). Good Vibrations: Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys in Critical Perspective. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11995-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leaf, David (1985). The Beach Boys. Courage Books. ISBN 978-0-89471-412-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Love, Mike (2016). Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-40886-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matijas-Mecca, Christian (2017). The Words and Music of Brian Wilson. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3899-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Priore, Domenic (1995). Look, Listen, Vibrate, Smile!. Last Gap. ISBN 978-0-86719-417-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Priore, Domenic (2005). Smile: The Story of Brian Wilson's Lost Masterpiece. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 978-1860746277.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sanchez, Luis (2014). The Beach Boys' Smile. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62356-956-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2007). Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313338458.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)