Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury | |

|---|---|

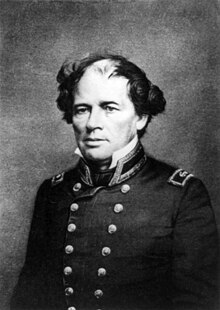

Lieut. Matthew Fontaine Maury, U.S. Navy | |

| Born | January 14, 1806 |

| Died | February 1, 1873 (aged 67) Lexington, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Oceanographer, naval officer, educator, author |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1825–1861 (USN) 1861–1865 (CSN) |

| Rank | |

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806 – February 1, 1873) was an American astronomer, United States Navy officer, historian, oceanographer, meteorologist, cartographer, author, geologist, and educator.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and "Father of Modern Oceanography and Naval Meteorology" and later, "Scientist of the Seas" for his extensive works in his books, especially The Physical Geography of the Sea (1855), the first such extensive and comprehensive book on oceanography to be published. Maury made many important new contributions to charting winds and ocean currents, including ocean lanes for passing ships at sea.

In 1825, at 19, Maury obtained, through US Representative Sam Houston, a midshipman's warrant in the United States Navy.[1] As a midshipman on board the frigate USS Brandywine, he almost immediately began to study the seas and record methods of navigation. When a leg injury left him unfit for sea duty, Maury devoted his time to the study of navigation, meteorology, winds, and currents. He became Superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory and head of the Depot of Charts and Instruments. There, Maury studied thousands of ships' logs and charts. He published the Wind and Current Chart of the North Atlantic Ocean, which showed sailors how to use the ocean's currents and winds to their advantage, drastically reducing the length of ocean voyages. Maury's uniform system of recording oceanographic data was adopted by navies and merchant marines around the world and was used to develop charts for all the major trade routes.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, Maury, a Virginian, resigned his commission as a US Navy commander and joined the Confederacy. He spent the war in the South as well as abroad, in Great Britain, Ireland, and France. He helped acquire a ship, CSS Georgia, for the Confederacy while he also advocated stopping the war in America among several European nations. Following the war, Maury accepted a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia. He died at the institute in 1873, after he had completed an exhausting state-to-state lecture tour on national and international weather forecasting on land. He had also completed his book, Geological Survey of Virginia, and a new series of geography for young people.

Early life and career

Maury was a descendant of the Maury family, a prominent Virginia family of Huguenot ancestry that can be traced back to 15th-century France. His grandfather (the Reverend James Maury) was an inspiring teacher to a future US president, Thomas Jefferson. Maury also had Dutch-American ancestry from the "Minor" family of early Virginia.

He was born in 1806 in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near Fredericksburg; his parents were Richard Maury and Diane Minor Maury. The family moved to Franklin, Tennessee, when he was five. He wanted to emulate the naval career of his older brother, Flag Lieutenant John Minor Maury, who, however, caught yellow fever after fighting pirates as an officer in the US Navy. As a result of John's painful death, Matthew's father, Richard, forbade him from joining the Navy. Maury strongly considered attending West Point to get a better education than the Navy could offer at that time, but instead, he obtained a naval appointment through the influence of Tennessee Representative Sam Houston, a family friend, in 1825, at the age of 19.

Maury joined the Navy as a midshipman on board the frigate Brandywine which was carrying the Marquis de La Fayette home to France, following La Fayette's famous visit to the United States. Almost immediately, Maury began to study the seas and to record methods of navigation. One of the experiences that piqued this interest was a circumnavigation of the globe on the USS Vincennes, his assigned ship and the first US warship to travel around the world.

Scientific career

His seagoing days came to an abrupt end at the age of 33, after a stagecoach accident broke his right leg. Thereafter, he devoted his time to the study of naval meteorology, navigation, charting the winds and currents, seeking the "Paths of the Seas" mentioned in Psalms 8:8 as: "The fowl of the air, and the fish of the sea, and whatsoever passeth through the paths of the seas." Maury had known of the Psalms of David since childhood. In A Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury (compiled by his daughter, Diana Fontaine Maury Corbin, 1888), she states on pages 7–8:

- "Matthew's father was very exact in the religious training of his family, now numbering five sons and four daughters, viz., John Minor, Mary, Walker, Matilda, Betsy, Richard Launcelot, Matthew Fontaine, Catherine, and Charles. He would assemble them night and morning to read the Psalter for the day, verse and verse about; and in this way, so familiar did this barefooted boy [M. F. Maury] become with the Psalms of David, that in after life he could cite a quotation, and give chapter and verse, as if he had the Bible open before him. His Bible is depicted on his monument beside his left leg. (See enlarged image on this page)[2]

As officer-in-charge of the United States Navy office in Washington, DC, called the "Depot of Charts and Instruments," the young lieutenant became a librarian of the many unorganized log books and records in 1842. On his initiative, he sought to improve seamanship through organizing the information in his office and instituting a reporting system among the nation's shipmasters to gather further information on sea conditions and observations. The product of his work was international recognition and the publication in 1847 of "Wind and Current Chart of the North Atlantic."[3] His international recognition assisted in the change of purpose and name of the depot to the United States Naval Observatory and Hydrographical Office in 1854.[3] He held that position until his resignation in April 1861. Maury was one of the principal advocates for the founding of a national observatory, and he appealed to a science enthusiast and former US President, Representative John Quincy Adams, for the creation of what would eventually become the Naval Observatory. Maury occasionally hosted Adams, who enjoyed astronomy as an avocation, at the Naval Observatory. Concerned that Maury always had a long trek to and from his home on upper Pennsylvania Avenue, Adams introduced an appropriations bill that funded a Superintendent's House on the Observatory grounds. Adams thus felt no constraint in regularly stopping by for a look through the facility's telescope.

As a sailor, Maury noted that there were numerous lessons that had been learned by ship masters about the effects of adverse winds and drift currents on the path of a ship. The captains recorded the lessons faithfully in their logbooks, but they were then forgotten. At the Observatory, Maury uncovered an enormous collection of thousands of old ships' logs and charts in storage in trunks dating back to the start of the US Navy.[4] He pored over the documents to collect information on winds, calms, and currents for all seas in all seasons. His dream was to put that information in the hands of all captains.[5]

Maury also used the old ships' logs to chart the migration of whales. Whalers at the time went to sea, sometimes for years, without knowing that whales migrate and that their paths could be charted.

Maury's work on ocean currents led him to advocate his theory of the Northwest Passage, as well as the hypothesis that an area in the ocean near the North Pole is occasionally free of ice. The reasoning behind that was sound. Logs of old whaler ships indicated the designs and the markings of harpoons. Harpoons found in captured whales in the Atlantic had been shot by ships in the Pacific and vice versa at a frequency that would have been impossible if the whales had traveled around Cape Horn.

Maury, knowing the whale to be a mammal, theorized that a northern passage between the oceans that was free of ice must exist to enable whales to surface to breathe. That became a popular idea that inspired many explorers to seek a reliably navigable sea route. Many of them died in their search for it.

Lieutenant Maury published his Wind and Current Chart of the North Atlantic, which showed sailors how to use the ocean's currents and winds to their advantage and to drastically reduce the length of voyages. His Sailing Directions and Physical Geography of the Seas and Its Meteorology remain standard. Maury's uniform system of recording synoptic oceanographic data was adopted by navies and merchant marines around the world and was used to develop charts for all the major trade routes.

Maury's Naval Observatory team included midshipmen assigned to him: James Melville Gilliss, Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke, William Lewis Herndon, Lardner Gibbon, Isaac Strain, John "Jack" Minor Maury II of the USN 1854 Darien Exploration Expedition, and others. Their duty was always temporary at the Observatory, and new men had to be trained over and over again. Thus Lt. Maury was employed with astronomical work and nautical work at the same time and constantly training new temporary men to assist in these works. As his reputation grew, the competition among young midshipmen to be assigned to work with him intensified. He always had able, though constantly changing, assistants.

Maury advocated much in the way of naval reform, including a school for the Navy that would rival the Army's West Point. That reform was heavily pushed by Maury's many "Scraps from the Lucky Bag" and other articles printed in the newspapers, bringing about many changes in the Navy, including his finally fulfilled dream of the creation of the United States Naval Academy.

During its first 1848 meeting, he helped launch the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

In 1849, Maury spoke out on the need for a transcontinental railroad to join the Eastern United States to California. He recommended a southerly route with Memphis, Tennessee, as the eastern terminus, as it is equidistant from Lake Michigan and the Gulf of Mexico. He argued that a southerly route running through Texas would avoid winter snows and could open up commerce with the northern states of Mexico. Maury also advocated construction of a railroad across the Isthmus of Panama.[6]

International meteorological conference

Maury also called for an international sea and land weather service. Having charted the seas and currents, he worked on charting land weather forecasting. Congress refused to appropriate funds for a land system of weather observations.

Maury early became convinced that adequate scientific knowledge of the sea could be obtained only by international co-operation. He proposed for the United States to invite the maritime nations of the world to a conference to establish a "universal system" of meteorology, and he was the leading spirit of a pioneer scientific conference when it met in Brussels in 1853. Within a few years, nations owning three fourths of the shipping of the world were sending their oceanographic observations to Maury at the Naval Observatory, where the information was evaluated and the results given worldwide distribution.[7]

As its representative at the conference, the US sent Maury. As a result of the Brussels Conference, a large number of nations, including many traditional enemies, agreed to co-operate in the sharing of land and sea weather data using uniform standards.[5] It was soon after the Brussels conference that Prussia, Spain, Sardinia, the Free City of Hamburg, the Republic of Bremen, Chile, Austria, and Brazil, and others agreed to joined the enterprise.

The Pope established honorary flags of distinction for the ships of the Papal States, which could be awarded only to the vessels that filled out and sent to Maury in Washington, DC, the Maury abstract logs.[8]

Attempted liquidation of United States slaves abroad

In 1851, Maury sent his cousin, Lieutenant William Lewis Herndon, and another former coworker at the United States Naval Observatory, Lieutenant Lardner Gibbon, to explore the valley of the Amazon, while gathering as much information as possible for both trade and slavery in the area. Maury thought the Amazon might serve as a "safety valve" by allowing Southern slaveowners to resettle or sell their slaves there. (Maury's plan was basically following the idea of northern slave traders and slaveholders who had sold their slaves to the Southern states.) The expedition aimed to map the area for the day when slave owners would go "with their goods and chattels to settle and to trade goods from South American countries along the river highways of the Amazon valley."[9] Brazil's slavery was extinguished after a slow process that began with the end of the international traffic in slaves in 1850 but did not end with complete abolition of slavery until 1888. Maury knew, when he wrote in the news journals of the day, that Brazil was bringing in new slaves from Africa. He proposed that moving the slaves in the United States to Brazil would reduce or eliminate slavery in time in as many areas of the United States as possible. He also hoped to stop the bringing of new slaves to Brazil. "Imagine," Maury wrote to his cousin, "waking up some day and finding our country free of slavery!"[10][2]

Maury started a campaign to force the Brazilian government to open up navigation in the Amazon River and to oblige it to receive American colonizers and trade. However, Emperor Pedro II's government firmly rejected the proposals. It was mindful of the background of previous American territorial annexations of parts of Mexico: immigration, provocation, conflict and annexation. Brazil thus acted diplomatically and through the press to avoid, by all means, the colonization proposed by Maury. By 1855, the project had certainly failed. Brazil authorized free navigation to all nations in the Amazon in 1866 but only when it was at war against Paraguay and free navigation in the area had become necessary.[11]

American Civil War

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, Maury, a native of Virginia, ended the career that he dearly loved by handing in his commission as a US Navy commander to serve Virginia, which had joined the Confederacy, as Chief of Sea Coast, River and Harbor Defenses. Because he was an international figure, he was ordered to go abroad for many reasons, including disseminating propaganda for the Confederacy, pursuing peace, and purchasing ships. He went to England, Ireland, and France, acquiring ships and supplies for the Confederacy. By speeches and newspaper publications, Maury tried desperately to get other nations to stop the American Civil War, carrying pleas for peace in one hand and a sword in the other, both to deal with whatever the outcome.

Confederate Congress appointed him a commissioner of Weights and Measures, in association with Francis H. Smith, a mathematics professor of the University of Virginia.[12]

Maury also perfected an "electric torpedo" (naval mine), which raised havoc with northern shipping. He had experience with the transatlantic cable and electricity flowing through wires underwater when working with Cyrus West Field and Samuel Finley Breese Morse. The torpedoes, similar to present-day contact mines, were said by the Secretary of the Navy in 1865 "to have cost the Union more vessels than all other causes combined."[5]

Later life

The war brought ruin to many in Fredericksburg, where Maury's immediate family lived. Thus, returning there was not immediately considered. After the war, after serving Maximilian in Mexico as "Imperial Commissioner of Immigration" and building Carlotta and New Virginia Colony for displaced Confederates and immigrants from other lands, Maury accepted a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute, holding the chair of physics.

Maury advocated the creation of an agricultural college to complement the institute. That led to the establishment of the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (Virginia Tech) in Blacksburg, Virginia, in 1872.[13] He declined the offer to become its first president partly because of his age. He had previously been suggested as president of the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1848 by Benjamin Blake Minor in his publication the Southern Literary Messenger. He considered becoming president of St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland, the University of Alabama, and the University of Tennessee.[14] It appears that he preferred being close to General Robert E. Lee in Lexington from statements that he made in letters. Maury served as a pall bearer for Lee.[15]

During his time at Virginia Military Institute, Maury wrote a book, The Physical Geography of Virginia. He had once been a gold mining superintendent outside Fredericksburg and had studied geology intensely during that time and so was well equipped to write such a book. During the Civil War, more battles took place in Virginia than in any other state, and his aim was to assist wartorn Virginia in discovering and extracting minerals, improving farming and whatever else could assist it to rebuild after such a massive destruction.

Maury later gave talks in Europe about co-operation on a weather bureau for land, just as he had charted the winds and predicted storms at sea many years before. He gave the speeches until his last days, when he collapsed giving a speech. He went home after he recovered and told his wife Ann Hull Herndon-Maury, "I have come home to die."

Death and burial

He died at home in Lexington at 12:40 pm, on Saturday, February 1, 1873. He was exhausted from traveling throughout the nation while he was giving speeches promoting land meteorology. He was attended by his eldest son, Major Richard Launcelot Maury and son-in-law, Major Spottswood Wellford Corbin. Maury asked his daughters and wife to leave the room. His last words were "all's well," a nautical expression telling of calm conditions at sea.[2]

His body was placed on display in the Virginia Military Institute library. Maury was initially buried in the Gilham family vault in Lexington's cemetery, across from Stonewall Jackson, until, after some delay into the next year, his remains were taken through Goshen Pass to Richmond, Virginia. He was reburied between Presidents James Monroe and John Tyler in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Legacy

After decades of national and international hard work averaging 14 hours per day, Maury received fame and honors, including being knighted by several nations and given medals with precious gems as well as a collection of all medals struck by Pope Pius IX during his pontificate, a book dedication and more from Father Angelo Secchi, who was a student of Maury from 1848 to 1849 in the United States Naval Observatory. The two remained lifelong friends. Other religious friends of Maury included James Hervey Otey, his former teacher who, before 1857, worked with Bishop Leonidas Polk on the construction of the University of the South in Tennessee. While visiting there, Maury was convinced by his old teacher to give the "cornerstone speech."

As a US Navy officer, he was required to decline awards from foreign nations. Some were offered to Maury's wife, Ann Hull Herndon-Maury, who accepted them for her husband. Some have been placed at Virginia Military Institute, others were lent to the Smithsonian, and yet others remain in the family. He became a commodore (often a title of courtesy) in the Virginia Provisional Navy and a commander in the Confederacy.

A monument to Maury, by sculptor Frederick William Sievers, was unveiled in Richmond on November 11, 1929. Maury Hall, the home of the Naval Science Department at the University of Virginia and headquarters of the University's Navy ROTC battalion, was named in his honor.[16] The original building of the College of William & Mary Virginia Institute of Marine Science is named Maury Hall as well. Another Maury Hall, named after him, houses the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department and the Systems Engineering Department at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Ships have been named in his honor, including various vessels named USS Maury; USS Commodore Maury (SP-656), a patrol vessel and minesweeper[17] of World War I; and a World War II Liberty Ship. Additionally, Tidewater Community College, based in Norfolk, Virginia, owns the R/V Matthew F. Maury.[18] The ship is used for oceanography research and student cruises. In March 2013, the US Navy launched the oceanographic survey ship USNS Maury.

Lake Maury, in Newport News, Virginia, is named after Maury. The lake is located on the Mariners' Museum property and is encircled by a walking trail. The Maury River, entirely in Rockbridge County, Virginia, near Virginia Military Institute (where Maury taught), also honors the scientist, as does Maury crater, on the Moon.

Matthew Fontaine Maury High School in Norfolk, Virginia, is named after him. Matthew Maury Elementary School in Alexandria, Virginia, was built in 1929.[19]

James Madison University has a Maury Hall named in his honor. It was the university's first academic and administrative building.[20]

Numerous historical markers commemorate Maury throughout the South, including those in Richmond, Virginia,[21] Fletcher, North Carolina,[22] Franklin, Tennessee,[23] and several in Chancellorsville, Virginia.[24]

Publications

- On the Navigation of Cape Horn

- Whaling Charts

- Wind and Current Charts

- Sailing Directions

- US Navy Contributions to Science and Commerce. 1847. Archived from the original on February 3, 1999.

- Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts, 1851, 1854, 1855

- Lieut. Maury's Investigations of the Winds and Currents of the Sea, 1851

- On the Probable Relation between Magnetism and the Circulation of the Atmosphere, 1851

- Maury's Wind and Current Charts: Gales in the Atlantic, 1857

- The Physical Geography of the Sea (1858 ed.). Harper & Brothers. 1855 – via Google Books.

- Observations to Determine the Solar Parallax, 1856

- Amazon, and the Atlantic Slopes of South America, 1853

- Commander M. F. Maury on American Affairs, 1861

- The Physical Geography of the Sea and Its Meteorology, 1861

- Maury's New Elements of Geography for Primary and Intermediate Classes

- Geography: "First Lessons"

- Elementary Geography: Designed for Primary and Intermediate Classes

- Geography: "The World We Live In"

- Published Address of Com. M. F. Maury, before the Fair of the Agricultural & Mechanical Society

- Geology: A Physical Survey of Virginia; Her Geographical Position, Its Commercial Advantages and National Importance, Virginia Military Institute, 1869

See also

Sources

- Flying Cloud – An 1851 true story of America's most famous clipper ship that raced other ships from New York, around Cape Horn, to San Francisco by using both Maury's Wind and Current Charts and his Sailing Directions. The clipper ship, Flying Cloud, was captained by Josiah Perkins Creesy and navigated by his wife, Eleanor Creesy, who was the first person to navigate around Cape Horn by using the new route laid down by then-Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury, of the National Observatory, at Washington. She used Maury's Sailing Directions and Winds and Currents. She gained and held the 89-day speed record of that route for decades. The old route was usually more than 100 days from New York, around the dangerous Cape Horn at the tip of South America and then onward to San Francisco. Source: Flying Cloud by David W. Shaw (copyright) 2001. ISBN 0-06-093478-6 (pbk.) and Physical Geography of the Sea (1855) by Matthew Fontaine Maury.

- Physical Geography of the Sea by Matthew Fontaine Maury 1855.

- Physical Geography of the Sea and its Meteorology by Matthew Fontaine Maury (1861).

- Wind and Current Charts by Matthew Fontaine Maury

- Sailing Directions by Matthew Fontaine Maury

- [1] Sky and Ocean Joined—The U.S. Naval Observatory 1830–2000 by Steven J. Dick (2003) ("The Maury Years" 1844–1861)

- The Pathfinder of the Seas, The Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury, by John W. Wayland, (1930). Professor Wayland writes, in the back of the book, under Chronology, that in 1916 the Virginia legislature created a law whereby "Maury Day " "..would be celebrated in all Virginia schools" (and it was); but it has been abandoned for unknown reasons.

- Tracks in the sea: Matthew Fontaine Maury and the Mapping of the Oceans by Chester G. Hearn (Camden, Maine: International Marine, 2002) ISBN 0-07-136826-4

- Prophet Without Honor a 1939 Academy Award-nominated short film biography of Matthew Fontaine Maury

References

- ^ Wikisource:Popular Science Monthly/Volume 37/July 1890/Sketch of Matthew Fontaine Maury

- ^ a b c Diana Fontaine Maury-Corbin "Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury USN & CSN" Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury, U.S.N. and C.S.N.

- ^ a b Bowditch, Nathaniel. (1966). "U.S. Hydrographic Office". American Practical Navigator: an Epitome of Navigation. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 31.

- ^ Penelope, Hardy (2016). "Every Ship a Floating Laboratory: Matthew Fontaine Maury and the Acquisition of Knowledge at Sea" in Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea 1800 - 1970. Science History Publications. p. 24. ISBN 9780881351446.

- ^ a b c David L. Cohn Pathfinder of the Seas. The Nautical Gazette, May '40

- ^ Sigafoos, R.A. Cotton Row to Beale Street: A business history of Memphis. Memphis State University Press, 1979. p. 19.

- ^ Frances L. Williams Matthew Fontaine Maury, Scientist of the Sea (1969) ISBN 0-8135-0433-3

- ^ Charles Lee Lewis, associate professor of the United States Naval Academy, Matthew Fontaine Maury: The Pathfinder of the Seas (1927) Annapolis. ISBN 0-405-13045-7 Reprinted (1980).

- ^ Charles C. Mann (2011), 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, Random House Digital, pp. 260–261, ISBN 978-0-307-59672-7

- ^ Letter to his cousin, dated National Observatory, December 24, 1851.

- ^ CERVO, A. L.; BUENO, C. History of Brazilian Foreign Politics. 4th edition. Brasilia: UnB, 2011, pp. 111 – 116

- ^ Tyler, Lyon Gardner, "Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography", Lewis Hist. Publ. Co., 1915, New York

- ^ Captain Miles P. DuVal, Jr., USN (Ret.). "Matthew Fontaine Maury: Benefactor of Mankind". Naval Historical Foundation. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Charles Lee Lewis (June 1980). Matthew Fontaine Maury. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-13045-8. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ Southern Historical Society's Papers

- ^ "U.Va. Web Map: Maury Hall". www.virginia.edu. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "USN Ships – USS Commodore Maury (SP-656), 1917–1918". Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ Research Vessel Matthew F. Maury (formerly PCF-2) Archived January 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "About Our School / History of Our School". www.acps.k12.va.us. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "James Madison University - Campus Map". www.jmu.edu. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ The Historical Marker Database: Matthew Fontaine Maury.

- ^ The Historical Marker Database: Matthew Fontaine Maury.

- ^ "Matthew Fontaine Maury - 3D 4 - Tennessee Historical Markers on Waymarking.com".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Historical Marker Database: Matthew Fontaine Maury: Pathfinder of the Seas, The Historical Marker Database: Matthew Fontaine Maury: Birthplace of Matthew Fontaine Maury (1806-1873) and The Historical Marker Database: Matthew Fontaine Maury: Maury House Trail.

External links

- Works by or about Matthew Fontaine Maury at the Internet Archive

- Images of Maury's medals and letters at the Wayback Machine (archived February 3, 1999). 1996 website retrieved via the Wayback Search Engine

- CBNnews VIDEO on Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury "The Father of Modern Oceanography"

- Naval Oceanographic Office—Matthew Fontaine Maury Oceanographic Library — The World's Largest Oceanographic Library.

- United States Naval Sea Cadet Corps — Matthew Fontaine Maury — Pathfinders Division.

- The Maury Project; A comprehensive national program of teacher enhancement based on studies of the physical foundations of oceanography.

- The Mariner's Museum: Matthew Fontaine Maury Society.

- Letter to President John Quincy Adams from Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury (1847) on the "National" United States Naval Observatory regarding a written description of the observatory, in detail, with other information relating thereto, including an explanation of the objects and uses of the various instruments.

- The National (Naval) Observatory and The Virginia Historical Society (May 1849)

- Biography of Matthew Fontaine Maury at U.S. Navy Historical Center.

- The Diary of Betty Herndon Maury, daughter of Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1861–1863.

- Matthew Fontaine Maury School in Richmond, Virginia, USA, 1950s. Photographer: Nina Leen. Approximately 200 TIME-LIFE photographs

- Astronomical Observations from the Naval Observatory 1845.

- Obituary in: . Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 2. April 1873.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|short=ignored (help) - Sample charts by Maury held the American Geographical Society Library, UW Milwaukee in the digital map collection.

- Matthew Fontaine Maury

- 1806 births

- 1873 deaths

- American astronomers

- American earth scientists

- American educators

- American geographers

- American oceanographers

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of French descent

- American Protestants

- American science writers

- Microscopists

- People from Spotsylvania County, Virginia

- People of Virginia in the American Civil War

- Science and technology in the United States

- United States Navy officers

- Writers from Virginia

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- Maury family of Virginia

- People from Franklin, Tennessee

- United States Navy