Theodore Hall

Theodore Hall | |

|---|---|

Hall's ID badge photo from Los Alamos | |

| Born | Theodore Alvin Holtzberg October 20, 1925 New York City, US |

| Died | November 1, 1999 (aged 74) Cambridge, England |

| Education | Harvard University University of Chicago[1] |

| Employer | Manhattan Project |

| Known for | Atomic espionage |

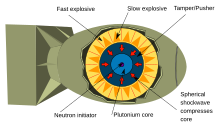

Theodore Alvin Hall (October 20, 1925 – November 1, 1999) was an American physicist and an atomic spy for the Soviet Union, who, during his work on US efforts to develop the first and second atomic bombs during World War II (the Manhattan Project), gave a detailed description of the "Fat Man" plutonium bomb, and of several processes for purifying plutonium, to Soviet intelligence.[2] His brother, Edward N. Hall, was a rocket scientist who worked on intercontinental ballistic missiles for the United States government.

Biography

Early years

Theodore Alvin Holtzberg was born in Far Rockaway, New York City to a devout Jewish couple, Barnett Holtzberg and Rose Moskowitz. His father was a furrier, and the Great Depression affected his business significantly. When his father's business became unable to support the household, the family moved to Washington Heights in Upper Manhattan.[2]

Even at a young age, Theodore showed an aptitude in mathematics and science, mostly being tutored by his elder brother Edward. After skipping three grades at Public School 173 in Washington Heights, in the fall of 1937, Hall entered the Townsend Harris High School for gifted boys.[2] After graduation from high school, he was accepted into Queens College at the age of 14 in 1940, and transferred to Harvard University in 1942, where he graduated at the age of 18 in 1944.[3][4]

From Holtzberg to Hall

In the fall of 1936, despite the protests of their parents, Edward, his brother, changed both his and Theodore's last name to Hall in an effort to avoid anti-Semitic hiring practices.[2][4]

Manhattan Project

At the age of 19, and through the recommendation of John Van Vleck, Hall was among the youngest scientists to be recruited to work on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos.[3][5] At Los Alamos, Hall handled experiments for the implosion device ("Fat Man") and helped determine the critical mass of uranium for "Little Boy".[2]

Theodore Hall later claimed that he became concerned about the consequences of an American monopoly of atomic weapons after the war. He was especially worried about the possibility of the emergence of a fascist government in the United States.[6]

While on a vacation in New York City in October 1944, he visited the CPUSA offices, instead of the Soviet Consulate (where he feared FBI surveillance), in order to locate a contact to pass information on the Manhattan Project along to the Soviet Union.[7] After a few recommendations, he met Sergey Kurnakov, a military writer for Soviet Russia Today and Russky Golos, and handed him a report on the scientists who worked at Los Alamos, the conditions at Los Alamos, and the basic science behind the bomb.[7] Saville Sax delivered the same report to the Soviet Consulate a few days later under the guise of inquiring about relatives still in the Soviet Union. The two eventually met with Anatoly Yatskov, the New York station chief, who later transmitted the information to the NKVD using a one-time pad cipher.[7] After officially becoming an informant for the Soviet Union, Hall was given the code-name MLAD, a Slavic root meaning "young", and Sax was given the code-name STAR, a Slavic root meaning "old".

Kurnakov reported in November 1944: "Rather tall, slender, brown-haired, pale and a bit pimply-faced, dressed carelessly, boots appear not cleaned for a long time, slipped socks. His hair is parted and often falls on his forehead. His English is highly cultured and rich. He answers quickly and very fluently, especially to scientific questions. Eyes are set closely together; evidently, neurasthenic. Perhaps because of premature mental development, he is witty and somewhat sarcastic but without a shadow of undue familiarity and cynicism. His main trait — a highly sensitive brain and quick responsiveness. In conversation, he is sharp and flexible as a sword ... He comes from a Jewish family, though doesn't look like a Jew. His father is a furrier; his mother is dead ... He is not in the army because, until now, young physicists in government jobs at a military installation were not being drafted. Now, he is to be drafted but has no doubts that he will be kept at the same place, only dressed in a military uniform and with a correspondingly lower salary."[8]

Unbeknownst to Hall, Klaus Fuchs, a Los Alamos colleague, and others still unidentified, were also spying for the USSR; none seems to have known of the others. Harvard friend Saville Sax acted as Hall's courier until spring of 1945 when he was replaced by Lona Cohen.[4][9] Igor Kurchatov, a brilliant scientist and the head of the Soviet atomic bomb effort, probably used information provided by Klaus Fuchs to confirm corresponding information provided earlier by Hall. Despite other scientists giving information to the Soviet Union, Hall was the only known scientist to give details on the design of an atomic bomb until recent revelations of the role of Oscar Seborer .[2]

Career after Los Alamos

In the autumn of 1946, Hall left Los Alamos for the University of Chicago, where he finished out his Master's and Doctoral degrees in Physics, met his wife, and started a family.[2][3] He continued feeding information to the Soviet Union about a new generation of nuclear weapons being developed at the University of Chicago.[4] After graduating he became a biophysicist.

In Chicago, he pioneered important techniques in X-ray microanalysis. In 1952 he left the University of Chicago's Institute for Radiobiology and Biophysics to take a research position in biophysics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City.[10] In 1962, he became unsatisfied with his equipment and the techniques available to him. He then moved to Vernon Ellis Cosslett's electron microscopy research laboratory at Cambridge University in England.[11] At Cambridge he created the Hall method of continuum normalization, developed for the specific purpose of analyzing thin sections of biological tissue.[3] He remained working at Cambridge until he retired at the age of 59 in 1984.

Hall later became active in obtaining signatures for the Stockholm Peace Pledge.[11]

Death

On November 1, 1999, Theodore Hall died at the age of 74, in Cambridge, England. Although he had suffered from Parkinson's disease, he ultimately succumbed to renal cancer.[5][12]

FBI investigation

The Venona project decrypted some Soviet messages and uncovered evidence about Hall, but until their public release in July 1995,[13] nearly all of the espionage regarding the Los Alamos nuclear weapons program was attributed to Klaus Fuchs. Hall was questioned by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in March 1951 but was not charged. Alan H. Belmont, the number-three man in the FBI, decided that information coming out of the Venona project would be inadmissible in court as hearsay evidence and so its value in the case was not worth compromising the program.[14]

Statements in 1990s

The Venona project became public knowledge in 1995.

In a written statement published in 1997, Hall came very close to admitting that the accusations against him were true, although obliquely, saying that in the immediate postwar years, he felt strongly that "an American monopoly" on nuclear weapons "was dangerous and should be avoided:"

To help prevent that monopoly I contemplated a brief encounter with a Soviet agent, just to inform them of the existence of the A-bomb project. I anticipated a very limited contact. With any luck, it might easily have turned out that way, but it was not to be.[15]

He repeated the near-confession in an interview for the TV-series Cold War on the Cable News Network in 1998, saying:

I decided to give atomic secrets to the Russians because it seemed to me that it was important that there should be no monopoly, which could turn one nation into a menace and turn it loose on the world as ... Nazi Germany developed. There seemed to be only one answer to what one should do. The right thing to do was to act to break the American monopoly.[14]

List of publications

- Steveninck, Reinhard; Steveninck, Margaret; Hall, Theodore; Peters, Patricia (1974). "A chlorine-free embedding medium for use in X-ray analytical electron microscope localisation of chloride in biological tissues". Histochemistry. 38 (2): 173–180. doi:10.1007/BF00499664.

- Normann, Tom; Hall, Theodore (1978). "Calcium and sulphur in neurosecretory granules and calcium in mitochondria as determined by electron microscope X-ray microanalysis". Cell and Tissue Research. 186 (3): 453–463. doi:10.1007/BF00224934.

- Civan, Mortimer; Hall, Theodore; Gupta, Brij (1980). "Microprobe study of toad urinary bladder in absence of serosal K+". The Journal of Membrane Biology. 55 (3): 187–202. doi:10.1007/BF01869460.

- Dow, Julian; Gupta, Brij; Hall, Theodore; Harvey, William (1984). "X-ray microanalysis of elements in frozen-hydrated sections of an electrogenic K + transport system: The posterior midgut of tobacco hornworm ( Manduca sexta) in vivo and in vitro". the Journal of Membrane Biology. 77 (3): 223–241. doi:10.1007/BF01870571.

See also

- Klaus Fuchs

- Oscar Seborer

- Saville Sax

- Lona Cohen

- Morris Cohen (spy)

- Manhattan Project

- Los Alamos

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Oppenheimer security hearing

- Atomic spies

- Soviet espionage in the United States

- Nuclear espionage

References

- ^ Read Venona Intercepts

- ^ a b c d e f g Albright, Joseph; Marcia Kunstel (1997). Bombshell: The Secret Story of America's Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy. New York: Times Book. ISBN 081292861X.

- ^ a b c d Goodrow, Genevieve; Richard Hopkin (December 2003). "Who was .... Theodore Hall?". Biologist. 50 (6): 282–283.

- ^ a b c d Sulick, Michael (2012). Spying in America: Espionage from the Revolutionary War to the Dawn of the Cold War. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. pp. 243–251. ISBN 978-1-58901-926-3.

- ^ a b Alan S. Cowell (November 10, 1999). "Theodore Hall, Prodigy and Atomic Spy, Dies at 74". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

Theodore Alvin Hall, who was the youngest physicist to work on the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos during World War II and was later identified as a Soviet spy, died on Nov. 1 in Cambridge, England, where he had become a respected, if not a truly leading, pioneer in biological research. He was 74.

- ^ http://spartacus-educational.com/Theodore_Hall.htm

- ^ a b c Haynes, John Earl; Harvey Klehr; Alexander Vassiliev (2009). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 110–117. ISBN 0300164386.

- ^ Sergei Kurnakov, report to NKVD headquarters (November, 1944)

- ^ McKnight, David (2002). Espionage and the Roots of the Cold war: The Constitutional Heritage. London: Frank Cass Publishers. p. 177. ISBN 0-7146-5163-X.

- ^ Albright, Joseph; Kunstel, Marcia (1997-04-09). "The Boy Who Gave Away the Atomic Bomb". New York Times. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- ^ a b Hastedt, Glenn (December 9, 2010). Spies, Wiretaps, and Secret Operations: An Encyclopedia of American Espionage. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 352. ISBN 1851098070.

- ^ Harold Jackson (November 16, 1999). "Theodore Hall. US scientist-spy who escaped prosecution and spent 30 years in biological research at Cambridge". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

Theodore Hall, who has died at the age of 74, was the American atomic scientist discovered by the United States authorities to have been a wartime Soviet spy – but who was never prosecuted. The information he gave Moscow was at least as sensitive as that which sent Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the electric chair. But the Americans decided not to charge Hall because of the security and legal difficulties of disclosing that they had penetrated some of the Soviet Union's most secure diplomatic codes. Subsequently, and with the tacit consent of the British security authorities, Hall spent more than 30 years as a respected researcher at Cambridge University until he retired in 1984, aged 59.

- ^ Kross, Peter (July 1, 2006). "The VENONA project revealed espionage in the United States after WWII--until it was in turn compromised". Military History. 23 (5): 70.

- ^ a b Ellen Dornan (2012). Forgotten Tales of New Mexico. The History Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-1-60949-485-8.

- ^ Alan Cowell (Nov. 10, 1999), "Theodore Hall, Prodigy and Atomic Spy, Dies at 74", The New York Times, p. C31

External links

- FBI: Memo Prosecution: Disadvantages (1 February 1956)

- "A Memoir of Ted Hall" at the Wayback Machine (archived June 7, 2007) (by Joan Hall, wife)

- Los Alamos National Laboratory: History: Spies

- Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues: Annotated bibliography for Theodore Hall

- "SECRETS, LIES, AND ATOMIC SPIES", PBS Transcript, Airdate: February 5, 2002

- 1925 births

- 1999 deaths

- People from Far Rockaway, Queens

- Jewish American scientists

- Nuclear secrecy

- Nuclear weapons program of the Soviet Union

- Manhattan Project people

- Harvard University alumni

- University of Chicago alumni

- People from Washington Heights, Manhattan

- World War II spies for the Soviet Union

- American spies for the Soviet Union

- American people in the Venona papers

- Townsend Harris High School alumni