Congress of Paris (1856)

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. |

The Congress of Paris was a diplomatic meeting held in Paris, France, in 1856,[1] between representatives of the great powers in Europe to make peace after the almost three-year-long Crimean War.

Before the Congress

The Crimean war was fought mainly on the Crimean Peninsula between Russia on one side, and Great Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire, and Sardinia on the other. It was fought mainly due to two reasons.

The Russians demanded better treatment of and wanted to protect the Orthodox subjects of the Sultan of Turkey.[2] This was later considered and promised by the Sultan of Turkey during the meeting at the Congress of Paris.

Also, there was a dispute between the Russians and the French regarding the privileges of the Russian Orthodox and the Roman Catholic Churches in Palestine.[2] With the backing of Britain, the Turks declared war on Russia on 4 October 1853.[2] On 28 March 1854, France and Britain also declared war against Russia.

Then, on 26 January 1855, Sardinia-Piedmont also entered the war against Russia by sending 10,000 troops to aid the allies.[2] Throughout the war, the Russian army's main concern was to make sure that Austria stayed out of the war. Still, Austria threatened to enter the war, causing peace.

The Congress

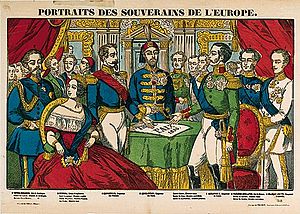

The great powers in Europe at the time were: France, Great Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia. Also present at the Congress were representatives of the Ottoman Empire and Piedmont-Sardinia.[1][3] They assembled soon after 1 February 1856, when Russia accepted the first set of peace terms after Austria threatened to enter the war on the side of the Allies. It is also notable that the meeting took place in Paris, just at the conclusion of the 1855 Universal Expo [2]

The Congress of Paris worked out the final terms from 25 February to 30 March 1856. The Treaty of Paris was then signed on 30 March 1856 with Russia on one side and France, Great Britain, Ottoman Turkey, and Sardinia-Piedmont on the other.[1] The group of men negotiated at the Quai d'Orsay.[4] One of the representatives who attended the Congress of Paris on behalf of the Ottoman Empire was Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, who was the grand vizier of the Empire.[4] Russia was represented by Prince Orlov and Baron Brunnov. Britain sent their Ambassador to France, who at the time was the Lord Cowley. While other congresses, such as the Congress of Vienna (1814), spread questions and issues for different committees to resolve, the Congress of Paris resolved everything in one group.[5]

A significant diplomatic victory was scored by tiny Piedmont that, although not being yet considered a "great" European power, was nevertheless granted a seat at the Congress by the French Emperor Napoleon III, mostly for having sent an expeditionary corps of 18,000 men to fight against Russia along with France and Prussia, but also possibly because of the intrigues of the very attractive Countess of Castiglione, who had caught the Emperor's attention. The Piedmontese foreign minister Camillo Benso di Cavour seized this opportunity to denounce Austrian political and military interference in the Italian peninsula that he said was stifling the wish of the Italian people to choose their own government.

Results of the Congress

The Congress resulted in a pledge by all of the powers to jointly maintain "the integrity of the Ottoman Empire". It also guaranteed Turkey's independence.[1]

Also, Russia gave up the left bank of the mouth of the Danube River, including part of Bessarabia[3] to Moldavia and gave up its claim to the special protection of Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Moldavia and Wallachia (which together later became Romania in 1858) along with Serbia were recognized as quasi-independent self-governing principalities under protection of the other European Powers. The sultan of Turkey agreed, in return, to help improve the status of the Christian subjects in his empire.[3]

The territories of Russia and Turkey were restored to their prewar boundaries.[3] The Black Sea was neutralized so that no warships were allowed to enter; however, it was open to all other nations.[3] It also opened the Danube River for shipping from all nations.[1]

Turkish historians still express dissatisfaction with this fact. By example: "Although Ottoman Empire was on the side of winners, the Porte also lost the right to have a navy in the Black Sea together with the Russia. Put differently, the Empire had become a part of the European Concert, but not an actor in the European balance of power. Thus it was not recognized as a great power that could claim compensation in case of territorial gain by another member of the system".[6]

The peace conditions of the Paris Congress collapsed with the defeat of France in the war with Prussia in 1870-71. After the capitulation of the fortress of Metz (after that, France actually lost hope to reverse the course of the war), Russia announced its refusal to comply with the terms of the Treaty of 1856. Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire Alexander Gorchakov on October 31, 1870 denounced the Black Sea clauses of the Treaty of Paris (1856).[7]

Some of the rules and agreements were altered later by the Congress of Berlin.[3]

References

R.R. Palmer, Joel Colton, Lloyd Kramer (2002). A History of the Modern World since 1815. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-250280-0.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c d e "Paris, Treaty of (1856)". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Volume 9. 15th ed. pp. 153-154. 2007.

- ^ a b c d e The Crimean War 1853- 1856. http://www.onwar.com/aced/data/cite/crimean1853.htm. 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "Congress of Paris". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-Paris-Co.html. 2008

- ^ a b Barchard, David. SETTING THE WORLD TO RIGHTS. http://www.cornucopia.net/highlights35.html. 2008

- ^ Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 938.

- ^ Candan Badem, The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856). Leiden-Boston.1970.p.403

- ^ This was documented by Treaty of London (1871).