Kalki

| Kalki | |

|---|---|

The tenth avatar of Vishnu | |

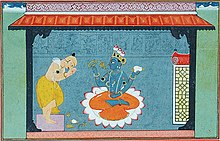

Kalki Avatar by Raja Ravi Varma | |

| Devanagari | कल्कि |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Kalki |

| Mount | Devadatta (i.e. White horse)[1][2] |

| Texts | Hinduism: Mahabharat Puranas Buddhism: Kalachakra-Tantra |

Kalki, also called Kalkin or Karki,[1] is the tenth avatar of Hindu god Vishnu to end the Kali Yuga, one of the four periods in the endless cycle of existence (krita) in Vaishnavism cosmology. He is described in the Puranas as the avatar who rejuvenates existence by ending the darkest and destructive period to remove adharma and ushering in the Satya Yuga, while riding a white horse with a fiery sword.[2] The description and details of Kalki are inconsistent among the Puranic texts. He is, for example, only an invisible force destroying evil and chaos in some texts [citation needed], while an actual person who kills those who persecute others, and portrayed as someone leading an army of Brahmin warriors in some. His mythology has been compared to the concepts of Messiah, Apocalypse, Frashokereti and Maitreya in other religions.[2][3]

Kalki is also found in Buddhist texts. In Tibetan Buddhism, the Kalachakra-Tantra'[4][5][6]

Etymology

The name Kalki is derived based Kal, which means "time" (kali yuga).[7] The literal meaning of Kalki is "dirty, sinful", which Brockington states does not make sense in the avatara context.[1] This has led scholars such as Otto Schrader to suggest that the original term may have been karki (white, from the horse) which morphed into Kalki. This proposal is supported by two versions of Mahabharata manuscripts (e.g. the G3.6 manuscript) that have been found, where the Sanskrit verses name the avatar to be "karki", rather than "kalki".[1]

Description

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

Kalki is an avatara of Vishnu. Avatara means "descent" and refers to a descent of the divine into the material realm of human existence. The Garuda Purana lists ten avatars, with Kalki being the tenth.[8] He is described as the avatar who appears at the end of the Kali Yuga. He ends the darkest, degenerating and chaotic stage of the Kali Yuga (period) to remove adharma and ushers in the Satya Yuga, while riding a white horse with a fiery sword.[2][3] He restarts a new cycle of time.[9] He is described as a Brahmin warrior in the Puranas.[2][3]

Wheel of Time Tantra

In the Buddhist text Kalachakra Tantra, the righteous kings are called Kalki (Kalkin, lit. chieftain) living in Sambhala. There are many Kalki in this text, each fighting barbarism, persecution and chaos. The last Kalki is called "Cakrin" and is predicted to end the chaos and degeneration by assembling a large army to eradicate the "forces of evil".[4][5] A great war and Armageddon will destroy the barbaric Muslim forces, states the text.[4][5][6] According to Donald Lopez – a professor of Buddhist Studies, Kalki is predicted to start the new cycle of perfect era where "Buddhism will flourish, people will live long, happy lives and righteousness will reign supreme".[4] The text is significant in establishing the chronology of the Kalki idea to be from post-7th century, probably the 9th or 10th century.[10] Lopez states that the Buddhist text likely borrowed it from Hindu mythology.[4][5] Other scholars, such as Yijiu Jin, state that the text originated in Central Asia in the 10th-century, and Tibetan literature picked up a version of it in India around 1027 CE.[10]

Development

There is no mention of Kalki in the Vedic literature.[11][12] The epithet "Kalmallkinam", meaning "brilliant remover of darkness", is found in the Vedic literature for Rudra (later Shiva), which has been interpreted to be "forerunner of Kalki".[11]

Kalki appears for the first time in the great war epic Mahabharata.[13] The mention of Kalki in the Mahabharata occurs only once, over the verses 3.188.85–3.189.6.[1] The Kalki avatar is found in the Maha-Puranas such as Vishnu Purana,[14] Matsya Purana, and Bhagavata Purana.[15][16] However, the details relating the Kalki mythologies are divergent between the Epic and the Puranas, as well as within the Puranas.[17][13]

In the Mahabharata, according to Hiltebeitel, Kalki is an extension of the Parasurama avatar legend where a Brahmin warrior destroys Kshatriyas who were abusing their power to spread chaos, evil and persecution of the powerless. The Epic character of Kalki restores dharma, restores justice in the world, but does not end the cycle of existence.[13][18] The Kalkin section in the Mahabharata occurs in the Markandeya section. There, states Luis Reimann, can "hardly be any doubt that the Markandeya section is a late addition to the Epic. Making Yudhisthira ask a question about conditions at the end of Kali and the beginning of Krta — something far removed from his own situation — is merely a device for justifying the inclusion of this subject matter in the Epic."[19]

According to Cornelia Dimmitt, the "clear and tidy" systematization of Kalki and the remaining nine avatars of Vishnu is not found in any of the Maha-Puranas.[20] The coverage of Kalki in these Hindu texts is scant, in contrast to the legends of Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Vamana, Narasimha and Krishna, all of which are repeatedly and extensively described. According to Dimmitt, this was likely because just like the concept of the Buddha as a Vishnu avatar, the concept of Kalki was "somewhat in flux" when the major Puranas were being compiled.[20][20]

This myth may have developed in the Hindu texts both as a reaction to the invasions of the Indian subcontinent by various armies over the centuries from its northwest, and the mythologies these invaders brought with them.[1][21]

According to John Mitchiner, the Kalki concept was likely borrowed "in some measure from similar Jewish, Christian, Zoroastrian and other religions".[22] Mitchiner states that some Puranas such as the Yuga Purana do not mention Kalki and offer a different cosmology than the other Puranas. The Yuga Purana mythologizes in greater details the post-Maurya era Indo-Greek and Saka era, while the Manvantara theme containing the Kalki idea is mythologized greater in other Puranas.[23][13] Luis Gonzales-Reimann concurs with Mitchiner, stating that the Yuga Purana does not mention Kalki.[24] In other texts such as the sections 2.36 and 2.37 of the Vayu Purana, states Reimann, it is not Kalkin who ends the Kali Yuga, but a different character named Pramiti.[25] Most historians, states Arvind Sharma, link the development of Kalki mythology in Hinduism to the suffering caused by foreign invasions.[26]

Kalki Purana

A minor text named Kalki Purana is a relatively recent text, likely composed in Bengal. Its dating floruit is the 18th-century.[27] Wendy Doniger dates the Kalki mythology containing Kalki Purana to between 1500 and 1700 CE.[28]

In the Kalki Purana, Kalki marries princess Padmavati, the daughter of Brhadratha of Simhala.[27] He fights an evil army and many wars, ends evil but does not end existence. Kalki returns to Sambhala, inaugurates a new yuga for the good and then goes to heaven.[27]

Kalki Avatar in Sikhism

The Kalki avatar appears in the historic Sikh texts, most notably in Dasam Granth as Nihakalanki, a text that is traditionally attributed to Guru Gobind Singh.[29][30] The Chaubis Avatar (24 avatars) section mentions sage Matsyanra describing the appearance of Vishnu avatars to fight evil, greed, violence and ignorance. It includes Kalki as the twenty-fourth incarnation to lead the war between the forces of righteousness and unrighteousness, states Dhavan.[31]

Features and iconography

[Lord Shiva said to Lord Kalki:] "This horse was manifested from Garuda, and it can go anywhere at will and assume many different forms. Here also is a parrot [ Shuka ] that knows everything - past, present, and future. I would like to offer You both the horse and the parrot and so please accept them. By the influence of this horse and parrot, the people of the world will know You as a learned scholar of all scriptures who is a master of the art of releasing arrows, and thus the conqueror of all. I would also like to present You this sharp, strong sword and so please accept it. The handle of this sword is bedecked with jewels, and it is extremely powerful. As such, the sword will help You to reduce the heavy burden of the earth."[32]

Thereafter, Lord Kalki picked up His brightly shining trident and bow and arrows and set out from His palace, riding upon His victorious horse and wearing His amulet.[33]

[Shuka said to Padmavati:] [Lord Kalki] received a sword, horse, parrot, and shield from Mahadeva, as a benediction.[34]

Predictions about birth and arrival

In the cyclic concept of time (Puranic Kalpa), Kaliyuga is variously estimated to last between 400,000 and 432,000 years. In some Vaishnava texts, Kalki is forecasted to appear on a white horse, at the end of Kaliyuga, to end the age of degeneration and to restore virtue and world order.[35][36]

Kalki is described differently in Indian and non-Indian Buddhist manuscripts. The Indian texts state that Kalki will be born to Awejsirdenee and Bishenjun,[35] or alternatively in the family of Sumati and Vishnuyasha.[37][38] He appears at the end of Kali Yuga to restore the order of the world.[35][36] Vishnuyasha is stated to be a prominent Brahmin headman of the village called Shambhala. He will become the king, a "Turner of the Wheel", and one who triumphs. He will eliminate all barbarians and robbers, end adharma, restart dharma, and save the good people.[39] After that, humanity will be transformed and will prevail on earth, and the golden age will begin.[39]

In the Kanchipuram temple, two relief Puranic panels depict Kalki, one relating to lunar (daughter-based) dynasty as mother of Kalki and another to solar (son-based) dynasty as father of Kalki.[37] In these panels, states D Dennis Hudson, the story depicted is in terms of Kalki fighting and defeating asura Kali. He rides a white horse called Devadatta, ends evil, purifies everyone's minds and consciousness, and heralds the start of Krita Yuga.[37]

People who claimed to be Kalki

List of people who have claimed to be the Kalki avatar:

- Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, founder of Ahmadiyya movement, claimed to be the Kalki Avatar, as well as Mahdi.[40]

- In the Bahá'í Faith, Bahá'u'lláh is identified as Kalki as well as the prophesied redeeming God at the end of the world, as claimed in Babism, Islam (Mahdi), Christianity (Messiah) and Buddhism (Maitreya).[41][42]

- Various Shia Muslim missionaries in South Asia – such as Siddiq Hussain – seeking to convert Hindus to their sect of Islam; they either claimed themselves to be Kalki, or claimed that "all" the Shia Imams were Kalki, or claimed Muhammad was Kalki.[43][44]

- Sri Bhagavan, of Golden Age Foundation, Bhagavad Dharma, Kalki Dharma and the Oneness Organisation, born on 7 March 1949.[45]

- Samael Aun Weor, founder of the Universal Christian Gnostic Movement.[46]

- Riaz Ahmed Gohar Shahi of Kalki Avatar Foundation.[47]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL Academic. pp. 287–288 with footnotes 126–127. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

- ^ a b c d e Dalal 2014, p. 188

- ^ a b c Wendy Doniger; Merriam-Webster, Inc (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 659. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ^ a b c d e Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2015). Buddhism in Practice. Princeton University Press. pp. 202–204. ISBN 978-1-4008-8007-2.

- ^ a b c d Perry Schmidt-Leukel (2017). Religious Pluralism and Interreligious Theology: The Gifford Lectures. Orbis. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-1-60833-695-1.

- ^ a b [a] Björn Dahla (2006). Exercising Power: The Role of Religions in Concord and Conflict. Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-952-12-1811-8., Quote: "(...) the Shambala-bodhisattva-king [Cakravartin Kalkin] and his army will defeat and destroy the enemy army, the barbarian Muslim army and their religion, in a kind of Buddhist Armadgeddon. Thereafter Buddhism will prevail.";

[b] David Burton (2017). Buddhism: A Contemporary Philosophical Investigation. Taylor & Francis. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-351-83859-7.

[c] Johan Elverskog (2011). Anna Akasoy; et al. (eds.). Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 293–310. ISBN 978-0-7546-6956-2. - ^ Klaus K. Klostermaier (2006). Mythologies and Philosophies of Salvation in the Theistic Traditions of India. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-88920-743-1.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 73.

- ^ Ludo Rocher (22 March 2004). Ralph M. Rosen (ed.). Time and Temporality in the Ancient World. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. pp. 91–93. ISBN 978-1-931707-67-1.

- ^ a b Yijiu JIN (2017). Evil. BRILL Academic. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-90-474-2800-8.

- ^ a b Tattvadīpaḥ: Journal of Academy of Sanskrit Research, Volume 5. The Academy. 2001. p. 81.

Kalki, as an incarnation of Visnu, is not found in the Vedic literature. But some of the features of that concept, viz., the fearful elements, the epithet Kalmallkinam (brilliant, remover of darkness) of Rudra, prompt us to admit him as the forerunner of Kalki.

- ^ Rabiprasad Mishra (2000). Theory of Incarnation: Its Origin and Development in the Light of Vedic and Purāṇic References. Pratibha. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-7702-021-2., Quote: "Kalki as an incarnation of Visnu is not mentioned in the Vedic literature."

- ^ a b c d Alf Hiltebeitel (2011). Reading the Fifth Veda: Studies on the Mahābhārata - Essays by Alf Hiltebeitel. BRILL Academic. pp. 89–110, 530–531. ISBN 978-90-04-18566-1.

- ^ Wilson, Horace (2001). Vishnu Purana. Ganesha Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 1-86210-016-0.

- ^ Roy, Janmajit. Theory of Avatāra and Divinity of Chaitanya. Atlantic Publishers. p. 39.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain. The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 181.

- ^ John E. Mitchiner (2000). Traditions Of The Seven Rsis. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 68–69 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-1324-3.

- ^ Alf Hiltebeitel (2011). Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative. Oxford University Press. pp. 288–292. ISBN 978-0-19-539423-8.

- ^ Luis González Reimann (2002). The Mahābhārata and the Yugas: India's Great Epic Poem and the Hindu System of World Ages. Peter Lang. pp. 89–99, quote is on page 97. ISBN 978-0-8204-5530-3.

- ^ a b c Dimmitt & van Buitenen 2012, pp. 63–64

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2004). Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook Translated from the Sanskrit. Penguin Books. pp. 235–237. ISBN 978-0-14-044990-7.

- ^ John E. Mitchiner (2000). Traditions Of The Seven Rsis. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-81-208-1324-3.

- ^ John E. Mitchiner (2000). Traditions Of The Seven Rsis. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 69–76. ISBN 978-81-208-1324-3.

- ^ Luis González-Reimann (2002). The Mahābhārata and the Yugas: India's Great Epic Poem and the Hindu System of World Ages. Peter Lang. pp. 95–99. ISBN 978-0-8204-5530-3.

- ^ Luis González Reimann (2002). The Mahābhārata and the Yugas: India's Great Epic Poem and the Hindu System of World Ages. Peter Lang. pp. 112–113 note 39. ISBN 978-0-8204-5530-3.; Note: Reimann mentions some attempts to "identify both Pramiti and Kalkin with historical rulers".

- ^ Arvind Sharma (2012). Religious Studies and Comparative Methodology: The Case for Reciprocal Illumination. State University of New York Press. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-0-7914-8325-1.

- ^ a b c Rocher 1986, p. 183 with footnotes.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1988). Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism. Manchester University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7190-1867-1.

- ^ Robin Rinehart (2011). Debating the Dasam Granth. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-19-975506-6.

- ^ W. H. McLeod (2003). Sikhs of the Khalsa: A History of the Khalsa Rahit. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-19-565916-0.

- ^ Purnima Dhavan (2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 1 55–157, 186 note 32. ISBN 978-0-19-975655-1.

- ^ Bhumipati Das. Sri Kalki Purana. 2nd ed. India: Jai Nitai Press, 2011. pp. 33–34 (ch 3, text 25–27).

- ^ Bhumipati Das. Sri Kalki Purana. 2nd ed. India: Jai Nitai Press, 2011. p. 36 (ch 3, text 36).

- ^ Bhumipati Das. Sri Kalki Purana. 2nd ed. India: Jai Nitai Press, 2011. p. 84 (ch 8, text 24).

- ^ a b c Charles Russell Coulter; Patricia Turner (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge.

- ^ a b James R. Lewis; Inga B. Tollefsen. The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. p. 488.

- ^ a b c D Dennis Hudson (2008). The Body of God: An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram. Oxford University Press. pp. 333–340.

- ^ Rocher 1986, p. 183.

- ^ a b J.A.B. van Buitenen (1987). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2. University of Chicago Press. p. 597–598.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Mark (2006). Oxford Handbook of Global Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 520. ISBN 978-0-19-513798-9. , ISBN (Ten digit): 0195137981.

- ^ Daniel E Bassuk (1987). Incarnation in Hinduism and Christianity: The Myth of the God-Man. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-1-349-08642-9.

- ^ John M. Robertson (2012). Tough Guys and True Believers: Managing Authoritarian Men in the Psychotherapy Room. Routledge. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-136-81774-8.

- ^ Robinson, R.; Clarke, S. (2003). Religious Conversion in India: Modes, Motivations, and Meanings. Oxford University Press. pp. 44, 108–113. ISBN 978-0-19-566329-7.

- ^ Sikand, Y. (2004). Muslims in India Since 1947: Islamic Perspectives on Inter-Faith Relations. Taylor & Francis. pp. 162–171. ISBN 978-1-134-37825-8.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, Volume 2, p.488, James R. Lewis, Inga B. Tollefsen, Oxford University Press

- ^ "Who is Samael Aun Weor?". Samael.org. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Sikand, Yoginder (2008). Pseudo-messianic movements in contemporary Muslim South Asia. Global Media Publications. p. 100.

Bibliography

- Bryant, Edwin Francis (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803400-1.

- Dimmitt, Cornelia; van Buitenen, J. A. B. (2012). Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas. Temple University Press (1st Edition: 1977). ISBN 978-1-4399-0464-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dalal, Rosen (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. ISBN 978-8184752779.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

- Johnson, W.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861025-0.

- Rao, Velcheru Narayana (1993). "Purana as Brahminic Ideology". In Doniger Wendy (ed.). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1381-0.

- Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447025225.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links