COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

This article documents a current pandemic. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (March 2020) |

| 2020 coronavirus pandemic in the United States | |

|---|---|

Confirmed cases per million inhabitants | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | United States |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei, China[1] |

| Index case | Everett, Washington |

| Arrival date | January 15, 2020[2] (4 years, 11 months, 1 week and 4 days ago) |

| Confirmed cases | 137,294 (JHU)[3] 103,321 (CDC confirmed)[4] |

| Recovered | 961 (JHU)[3] |

Deaths | 2,010 (JHU)[3] 1,668 (CDC confirmed)[4] |

| Government website | |

| coronavirus | |

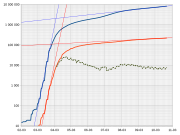

An ongoing worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a new infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first confirmed to have spread to the United States in January 2020. Cases have been confirmed in all fifty U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and all inhabited U.S. territories except American Samoa.[5] As of March 28, 2020[update], the U.S. has the most confirmed active cases in the world and ranks sixth in number of total deaths from the virus.[6]

The first known case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was confirmed on January 20, 2020, in a 35-year-old man who had returned from Wuhan, China, five days earlier.[2] The White House Coronavirus Task Force was established on January 29.[7] Two days later, the Trump administration declared a public health emergency and announced restrictions on travelers arriving from China.[8] On February 26, the first case in the U.S. in a person with "no known exposure to the virus through travel or close contact with a known infected individual" was confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in northern California.[9]

From January to mid-March, the United States got off to a slow start in COVID-19 testing.[10][11][12] In that period, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) procedures forbade laboratories that followed internationally recognized test protocols from releasing results to patients. The FDA approved only non-government test kits from late February and had restrictive test eligibility guidelines until early March. The CDC developed and distributed test kits of its own, many of which were found to have a manufacturing flaw in a non-essential component, which however made the kit illegal to use until the protocol was changed.[13][10][11] This was followed by the government announcing a series of measures intended to speed up testing. As of March 25, at least 418,000 tests had been conducted.[14] Private companies have begun to ship hundreds of thousands of tests. Drive-through testing stations are starting all over the country.[15] The CDC warned that widespread transmission may force large numbers of people to seek hospitalization and other healthcare, which may overload healthcare systems.[16] Since March 19, 2020, the Department of State has advised U.S. citizens to avoid all international travel.[17] The U.S. government has advised against any gathering of more than 10 people.[18]

In mid-March 2020, the federal government told the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to lease hotels and other buildings across the country, then hire contractors to convert them for use as hospital intensive care units staffed and operated by state governments.[19]

State and local responses to the outbreak have included prohibitions and cancellation of large-scale gatherings, including the closure of schools and other educational institutions, the cancellation of trade shows, conventions, and music festivals, and the cancellation and suspension of sporting events and leagues.[20]

History

The COVID-19 outbreak, which the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11,[20] has had a disparate impact on different areas of the U.S. Of the 154 deaths in the country prior to March 20, 94 occurred in the state of Washington, with 35 of those at one nursing home.[21] By late March, the epicenter of the outbreak in the United States had shifted to New York. The state accounted for 56% of all U.S. confirmed cases on March 25, but was showing signs of its growth rate of new cases potentially declining.[22] For the country as a whole, the mortality rate for confirmed coronavirus cases was 1.3% based on March 24 data. In comparison the other three most effected nations had significantly higher death rates of 4% in China, 9.8% in Italy, and 7.1% in Spain, while Germany in fifth place had a lower rate of .5%.[23]

Soon after the first COVID-19 case appeared in the United States in January, the Trump administration banned foreign nationals from entering the country from China and quarantined Americans returning from Hubei province, then a coronavirus hotspot. This is the first quarantine order the U.S. federal government has issued in over 50 years.[24]

In early March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advised against non-essential travel to China, Iran, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the 26 European countries that comprise the Schengen Area. The United States also denied entry to foreign nationals who had traveled through China, Iran, or the aforementioned European regions within the past 14 days. Americans returning home after traveling in these regions were required to undergo a health screening and submit to a 14-day quarantine.[25][26] Quarantines are governed by section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S. Code § 264).[27][28] Throughout March, several state, city, and county governments imposed "stay at home" quarantines on their populations, in order to stem the spread of the virus.[citation needed]

By mid-March, all 50 states were able to perform tests, with a doctor's approval, either from the CDC or from commercial labs in a state, but the number of available test kits remained limited,[29] which meant the true number of people infected with the virus was impossible to estimate with any reasonable accuracy at the time. The CDC suggested that doctors use their own judgment along with certain guidelines before authorizing a test. By March 12, diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. exceeded a thousand, which doubled every two days to reach more than 17,000 by March 20.[30][31]

Administration officials warned on March 19 that the number of cases would begin to rise sharply as the country's testing capacity substantially increased.[32] Around this time, the United States began running 50,000 to 70,000 coronavirus tests per day.[33] On March 26, the total number of confirmed cases surpassed that of China with over 85,000, making the U.S. the country with the highest number of coronavirus patients in the world.[34][35][36] The country reached another critical mark, as the number of positive cases surged over 100,000 the next day on March 27.[37]

Government responses

Task force formation

On January 29, 2020, President Trump established the White House Coronavirus Task Force to coordinate and oversee efforts to "monitor, prevent, contain, and mitigate the spread" of COVID-19 in the United States.[38] Secretary of HHS Alex Azar was appointed as the leader of the task force.[39][7] On February 26, Trump appointed Vice President Mike Pence to take charge of the nation's response to the virus.[40] FEMA was put in charge of procuring medical supplies on March 17.[41][42]

Containment and mitigation

The early phases of public health efforts for epidemics and pandemics are to contain or limit further outbreaks. Those actions will often involve tracing contacts, implementing quarantines, and isolating infectious cases. They will demand significant human resources and government staffing at all levels. As an outbreak grows, new facilities may need to be constructed to manage additional infectious cases.[43]

National medical organizations like the CDC focus on both containment to first keep the virus from spreading after its detection, and mitigation, to prevent it from spreading quickly beyond containment limits. The process of mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic is needed to extend its time frame by spreading out cases and isolating individuals, which slows the spread of the disease. By that means, it lowers the peak, or number of new cases, which reduces the likelihood of suddenly over-crowding doctors' offices and hospitals beyond their capacity.[44]

The risk of a truly global pandemic is limited for some diseases, such as Ebola, because of the slow pace of transmission or high probability of detection and containment. COVID-19 is at the other extreme, being a pathogen that has high potential to cause a severe pandemic, especially because it easily transmits between people and remains asymptomatic for a long period, thereby lengthening the time it is infectious and not detected.[43]

In general, once a pandemic has begun within a country's borders, the government must begin taking steps to curtail interactions between infected and uninfected populations. The methods used could include isolation of infected patients, quarantine, physical distancing practices, school closures, use of personal protective equipment, and travel restrictions.[43]

February 25 was the first day the CDC told the American public to prepare for an outbreak.[45]

Travel and entry restrictions

Chinese health authorities confirmed that they identified a cluster of a novel infectious coronavirus on December 31, 2019, in the city of Wuhan, officially reporting their findings on January 7, 2020. An American citizen, after traveling from Wuhan, China to his home in Washington state, became the first U.S. case of the new virus on January 20.[46] A few days later, Wuhan was placed under quarantine, soon to be followed by a quarantine of the entire Hubei province. On January 30, the WHO declared the new virus to be a global health emergency.[46]

President Trump imposed travel restrictions a day later preventing foreign nationals from entering the U.S. if they had been in China within the previous two weeks. The immediate family members of U.S. citizens and permanent residents were exempt from this restriction. In addition, Trump imposed a quarantine for up to 14 days on American citizens returning from Hubei province.[47] Although the WHO had recommended against travel restrictions at the time,[48] HHS Secretary Alex Azar said the decision stemmed from the recommendations of HHS health officials.[49] Trump expanded those travel restrictions to Iran on February 29.[49]

Over the following few weeks, the Trump administration imposed a number of other travel restrictions:

- In mid-February, the CDC, along with President Trump, opposed allowing fourteen people who had tested positive for COVID-19 while passengers on the cruise ship Diamond Princess to be flown back to the U.S. without completing a 14-day quarantine. They were overruled by officials at the U.S. State Department."[50]

- On March 12, the CDC recommended against any non-essential travel to China,[51] most of Europe,[52] Iran,[53] Malaysia,[54] and South Korea.[55][56] The following week, the U.S. Department of State recommended that U.S. citizens not travel abroad, while those who are abroad should "arrange for immediate return to the United States" unless prepared to remain abroad indefinitely.[57][58]

- On March 19, the State Department suspended routine visa services at all American embassies and consulates worldwide.[59]

- By March 20, the U.S. began barring entry to foreign nationals who had been in 28 European countries within the past 14 days. American citizens, permanent residents, and their immediate families returning from abroad can re-enter the United States under the new restrictions, but those returning from one of the specified countries must undergo health screenings and submit to quarantines and monitoring for up to 14 days. In addition to the earlier travel restrictions in place, Trump extended this quarantine and monitoring requirement to those coming from Iran and the entirety of China. Flights from all restricted countries are required to land at one of 13 airports where the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has "enhanced" entry screenings.[60][24] At least 241 foreigners (including several Canadians), who had recently traveled in China and Iran, were denied entry to the United States between February 2 and March 3.[61][62]

Containment efforts within the U.S.

As part of the early efforts to contain and mitigate the pandemic within the United States, Surgeon General Jerome Adams announced in early March that local leaders would soon have to consider whether to cancel large gatherings, consider telework policies, and close schools.[63] Over the next few weeks, a number of states imposed lockdown measures of different scope and severity, which placed limits on where people can travel, work and shop away from their homes.[64]

By March 21, Governors in New York, California and other large states, had ordered most businesses to close and for people to stay inside, with limited exceptions. The order in New York, for instance, exempts financial institutions, some retailers, pharmacies, hospitals, manufacturing plants and transportation companies, among others. It placed a ban on non-essential gatherings of any size and for any reason.[64]

In late March, the federal government planned to send California eight large medical stations which can house 2,000 hospital beds. Four more stations with 1,000 beds were planned for New York, and Washington state would be getting three large federal medical stations and four small stations with 1,000 beds.[65] In addition, more than a thousand rooms in Chicago hotels were to be made available to house patients who may be infected and should not be returning home. That would reduce unnecessary strain on local hospitals and would free up their beds for seriously ill patients. Those in the hotel would be serviced by regular hotel workers after they are properly trained, and will not directly interact with guests.[66] Another containment and care facility planned would be two Navy hospital ships.[67]

On the evening of 28 March, the president decided not to attempt to enact a tri-state lockdown of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, after having publicly suggested earlier in the day that he was considering such a move; instead he ordered the CDC to issue a travel advisory suggesting voluntary travel limitations in these states.[68]

COVID-19 testing

Beyond identifying whether a person is currently infected, coronavirus testing helps health professionals ascertain how bad the epidemic is and where it is worst.[69] However, the accuracy of national statistics on the number of cases and deaths from the outbreak depend on knowing how many people are being tested every day, and how the available tests are being allocated. But as of late March, most countries do not provide official reports on tests performed, therefore there is no centralized WHO data on COVID-19 testing.[70]

While the World Health Organization opted to use an approach developed by Germany to test for COVID-19, the United States developed its own testing approach. The German testing method was made public on January 13, and the American testing method was made public on January 28. The World Health Organization did not offer any test kits to the U.S. because the U.S. normally had the supplies to produce their own tests.[71] In February, the U.S. CDC produced 160,000 coronavirus tests, but soon it was discovered that many were defective and gave inaccurate readings.[10][72] Although academic laboratories and hospitals had developed their own tests, they were not allowed to use them until February 29, when the FDA issued approvals for them and private companies.[10] Approvals were required by federal law due to the outbreak being declared as a public health emergency.[15]

Meanwhile, from the start of the outbreak to early March 2020, the CDC gave restrictive guidelines on who should be eligible for COVID-19 testing. The initial criteria were (a) people who had recently traveled to certain countries affected by the outbreak, or (b) people with respiratory illness serious enough to require hospitalization, or (c) people who have been in contact with a person confirmed to have COVID-19. Only on March 5 did the CDC relax the criteria to allow doctors discretion to decide who would be eligible for tests.[11]

As a result, the United States had a slow start in conducting widespread testing for COVID-19.[73][74] Fewer than 4,000 tests were conducted in the U.S. by February 27, with U.S. state laboratories conducting only around 200.[10] The first U.S. case of a person having COVID-19 of unknown origin (a possible indication of community transmission in the state of California) saw the patient's test being delayed for four days after being hospitalized on February 19, because he had not qualified for a test under the initial federal testing criteria.[75] Whereas in Washington state, a group of researchers defied a lack of clearance from federal and state officials to conduct their own tests from February 25, using samples already collected from their flu study that their subjects had not given permission for COVID-19 testing. They quickly found a teenager infected with COVID-19 of unknown origin, newly indicating that an outbreak was already occurring in Washington. State regulators stopped these researchers' testing on March 2.[76]

On March 5, Vice President Mike Pence, the leader of the coronavirus response team, acknowledged that "we don't have enough tests" to meet the predicted future demand; this announcement came only three days after FDA commissioner Stephen Hahn committed to producing nearly a million tests by that week.[77] Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut and representative Stephen Lynch of Massachusetts both noted that as of March 8 their states had not yet received the new test kits.[78][79] Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, acknowledged on March 12 that it was "a failing" of the U.S. system that the demand for coronavirus tests were not being met; Fauci later clarified that he believed the private sector should have been brought in sooner to address the shortfall.[80] By March 13, fewer than 14,000 tests had been done in the United States, reported The Atlantic.[81]

The timing and availability of testing varies across countries. For example, by March 13 South Korea offered drive-through testing centers, which could get results the next day.[82] South Korea also had a government-funded daily testing capacity of 15,000.[83] According to March 16 and 17 statistics from Our World in Data, the U.S. had tested 125 people per million of their population—around the same as Japan. The U.K. tested nearly 750 per million, Italy more than 2,500 per million, and South Korea more than 5,500 per million.[84] The first COVID-19 cases in the U.S. and South Korea were identified at around the same time.[85] Critics say the U.S. government has botched the approval and distribution of test kits, losing crucial time during the early weeks of the outbreak, with the result that the true number of cases in the United States was impossible to estimate with any reasonable accuracy.[29][86]

As of March 12, all 50 states were able to perform tests, with a doctor's approval, either from the CDC or from commercial labs in a state.[87] This was followed by the government announcing a series of measures intended to speed up testing. These measures included the appointment of Admiral Brett Giroir of the U.S. Public Health Service to oversee testing, funding for two companies developing rapid tests, and a hotline to help labs find needed supplies.[88] The FDA also gave emergency authorization for New York to obtain an automated coronavirus test unit that will reduce the testing time to 3.5 hours.[89]

In a press conference on March 13, the Trump administration said tests would be conducted in retail store parking lots across the country, with participating franchises including Walmart, Target, CVS, and Walgreens. Trump added that the results would be sent to labs to complete testing in partnership with local health departments and diagnostic labs.[90] On March 13, drive-through testing in the U.S. began in New Rochelle, Westchester County, as New Rochelle was the U.S. town with the most diagnosed cases at that time.[91]

Research into vaccine and drug therapies

There is currently no drug that is approved for treating COVID-19 either as a therapy or a vaccine. Nor is there any clear evidence that COVID-19 infection leads to immunity, although experts assume it will for a period.[92] As of late March 2020, more than a hundred drugs are in testing.[93]

Among the labs working on a vaccine is the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, which has previously studied other infectious diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and MERS. Speed in developing a vaccine is a key element in the midst of the pandemic. By March 18, tests had begun with a few dozen volunteers in Seattle, Washington, which was sponsored by the U.S. government. Similar safety trials of other coronavirus vaccines will begin soon in the U.S. Trials are also underway in China and Europe.[94]

The search for a vaccine has taken on aspects of national security and global competition.[95] President Trump has directed the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to accelerate the testing and possible use of certain medications to find out if they would help treat coronavirus patients.[96] Among potential drugs, are chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which have long been used successfully to treat malaria. Both hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine are currently being used to treat coronavirus patients by a number of physicians with the limited approval of the FDA, which is allowing it as a compassionate use, although still under investigation.[96]

In China, trials of chloroquine are underway at dozens of clinics, with early laboratory results showing that it seemed to cut down the virus's rate of replication. Chloroquine has been used to treat patients with malaria for nearly a century.[97]

Like chloroquine, the closely-related drug hydroxychloroquine has already been used to treat certain autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.[97] A study in the peer-reviewed medical journal, Clinical Infectious Diseases, published on March 9 provided dosing recommendations for hydroxycholorquine as a COVID-19 treatment and showed it to be more effective in inhibiting the virus in vitro than chloroquine.[98] Doctors are currently testing hydroxycholoroquine in coronavirus patients.[97] On March 20, the WHO announced a large global trial of both drugs.[99]

Because there is little time to fully test the drug, some experts in the U.S. have suggested using it as a first-line treatment. The heads of the FDA and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, have been hesitant due to inherent risks. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo planned to study its potential beginning March 24.[100] However, there is currently a shortage of hydroxychloroquine, and some would like the federal government to release any stockpiles it may have and contract with generic manufacturers to ramp up production.[101] The French laboratory Sanofi, said it had the ability to provide millions of doses, enough to treat 300,000 patients, if it proved effective.[102] And the Israeli company Teva Pharmaceuticals, said it planned to manufacture and donate ten million doses to U.S. hospitals at no charge.[102]

Also being tested in research clinics is the antiviral drug remdesivir.[96] It was developed to fight Ebola, although it failed to prove effective for that disease.[97]

At a Coronavirus Task Force briefing on March 19, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen Hahn noted that the FDA had made remdesivir available for "compassionate use" for dying coronavirus patients, while the FDA standard approval process was still ongoing.[103] Due to the emergency nature of the pandemic, former FDA commissioners Drs. Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan have called for the FDA to develop therapeutics and vaccines that would be exempt from some regulatory requirements.[96]

Medical supplies

On March 15, senior federal health official Anthony Fauci said the United States had 12,700 ventilators in its national stockpile.[104] On March 19, Vice President Mike Pence declared that the federal government had "literally identified tens of thousands of ventilators", but did not provide further details.[105]

On March 16, Trump told state governors that for medical equipment including respirators and ventilators, "We will be backing you, but try getting it yourselves."[106] On March 24, Trump said that state governors who wanted help from the federal government "have to treat us well, also", because "it's a two-way street"; he warned against governors arguing "we should get this, we should get that".[107]

Trump signed the Defense Production Act on March 18, which allows the federal government a wide range of powers, including giving directions to industries on what to produce, having companies prioritize certain contracts, allocating supplies, giving incentives to industries, and allowing companies to cooperate. Initially under the act, he conferred more power over contracts and resources to the Health and Human Services Secretary and enacted provisions to prevent hoarding of medical resources.[108][109] He first invoked the act to direct industry production on March 27, instructing the HHS to compel General Motors to manufacture ventilators, after negotiations with the company stalled. He also appointed Peter Navarro to oversee enforcement of the act.[110]

On March 18, Trump remarked that the federal government purchased 500 million N-95 masks to make more private masks available and that American manufacturers were repurposing factories to manufacture masks.[111]

By March 21, the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security described American hospitals as already facing shortages of test kit reagents, test kit swabs, masks, gowns and gloves.[112]

Bloomberg News reported on March 25 that ventilator manufacturers are facing a shortage of sub-components needed to produce the ventilators.[113]

Congressional response

On March 6, 2020, President Trump signed into law the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, approved by both Houses to provide $8.3 billion to fight the pandemic. The deal includes "more than $3 billion for the research and development of vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics, as well as $2.2 billion for the CDC, and $950 million to support state and local health agencies".[114][115] Another bill, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act was approved on March 18. It provides paid emergency leave and food assistance be provided to affected employees, along with free testing.[116]

The U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, chaired by Representative Maxine Waters, released a stimulus proposal on March 18 in which the Federal Reserve would fund monthly payments of "at least $2,000 for every adult and an additional $1000 for every child for each month of the crisis". Other elements include suspending all consumer and small business credit payments.[117] On March 18, Representative Rashida Tlaib proposed the similar "Automatic BOOST to Communities Act", which would involve sending pre-loaded $2,000 debit cards to every American, with $1,000 monthly payments thereafter until the economy recovers. This would be funded by the U.S. Treasury minting two trillion-dollar coins. According to Tlaib, the Treasury has this authority, and it would not increase the national debt.[118]

With guidance from the White House, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell proposed a third stimulus package amounting to over $1 trillion.[a][b][c] On March 22 and 23, the $1.4 trillion package, known as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (or CARES Act), failed to pass in the Senate.[132][d][e] The act was revised in the Senate, coming to $2 trillion, including $500 billion for loans to larger businesses such as airlines, $350 billion for small business loans, $250 billion for individuals, $250 billion for unemployment insurance, $150 billion for state and municipal governments, and $130 billion for hospitals.[137] It passed unanimously in the Senate late the night of March 25.[138] On March 27, the House approved the stimulus bill, and it was signed into law by President Trump.[139]

Other federal policy responses

On March 3, 2020, the Federal Reserve lowered target interest rates from 1.75% to 1.25%,[140] the largest emergency rate cut since the 2008 global financial crisis,[141] in an attempt to counteract the outbreak's effect on the American economy. "The coronavirus poses evolving risks to economic activity," the Federal Reserve said in a statement. "In light of these risks and in support of achieving its maximum employment and price stability goals, the Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower the target range for the federal funds rate."[142]

On March 11, during his Oval Office address, Trump announced that he had requested a number of other policy changes:

- He would ask Congress to provide financial relief and paid sick leave for workers who were quarantined or had to care for others.

- He would instruct the Small Business Administration (SBA) to provide loans to businesses affected by the pandemic, and would ask Congress for an additional $50 billion to help hard-hit businesses.

- He would request that tax payments be deferred beyond April 15 without penalty for those affected, which he said could add $200 billion in temporary liquidity to the economy.

- He would ask Congress to provide payroll tax relief to those affected.[143]

On March 15, the Fed cut their target interest rate again to a range of 0% to 0.25%.[144] The Fed also announced a $700 billion quantitative easing program similar to the one initiated during the financial crisis of 2007–08. Despite the moves, stock index futures plunged, triggering trading limits to prevent panic selling.[145] The Dow lost nearly 13% the next day, the third-largest one-day decline in the 124-year history of the index.[146] That day, the VIX—informally known as the market "fear index"—closed at the highest level since its inception in 1990.[147]

On March 17, the Federal Reserve announced a program to buy as much as $1 trillion in corporate commercial paper to ensure credit continued flowing in the economy. The measure was backed by $10 billion in Treasury funds.[148] At this point, the federal government neared agreement on an economic stimulus proposal totaling about $1 trillion, including direct cash payments to Americans.[149] Trump said his administration was working with the Congress to provide rapid relief to affected industries. He remarked that the relief would ensure the American economy would emerge as the strongest on earth. In addition, Trump announced that Small Business Administration would be providing disaster loans which could provide impacted businesses with up to $2 million.[150]

On March 18, Trump announced that the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) would be suspending all kinds of foreclosures and evictions until the end of April.[151]

The week of March 19, the Federal Housing Finance Agency ordered federally-guaranteed loan providers to grant forbearance of up to 12 months on mortgage payments from people who lost income due to the pandemic. It encouraged the same for non-federal loans, and included a pass-through provision for landlords to grant forbearance to renters who lost income.[152]

On March 20, Trump announced that the Department of Education will not be enforcing standardized testing for 2020. Trump had also instructed to waive all federally held student loans for the next 60 days, which could be extended if needed.[153] Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin also announced that the deadline for all tax filings is moved to July 15.[154]

On March 22, Trump announced that he had directed FEMA to provide four large federal medical stations with 1,000 beds for New York, eight large federal medical stations with 2,000 beds for California, and three large federal medical stations and four small federal medical stations with 1,000 beds for the State of Washington.[155]

On March 23, the Federal Reserve announced large-scale expansion of quantitative easing, with no specific upper limit, and reactivation of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility. This injects newly created money into a variety of financial markets including corporate bonds, exchange-traded funds, small business loans, mortgage-backed securities, student loans, auto loans, and credit card loans. The Fed also lowered its repurchase agreement interest rate from 0.1% to 0%.[156] On the same day, Trump also postponed the October 1, 2020, deadline that required Americans on commercial airlines to carry Real ID-compliant documents.[157]

Communication

President Trump

From January 2020 to mid-March 2020, President Trump downplayed the threat posed by COVID-19 to the United States, giving many optimistic public statements,[158] which may have been aimed at calming stock markets.[159] He initially said he had no worries about COVID-19 becoming a pandemic.[160] He went to state on multiple occasions that the situation was "under control", and gave assurances that the country was already overcoming the outbreak. During a Black History Month reception on February 26, he said of the virus: "One day it's like a miracle, it will disappear." He quickly qualified this by adding: "[It] could maybe go away. We'll see what happens. Nobody really knows." He also cautioned that "it could get worse before it gets better."[161][158] In other remarks, he expressed a focus on the number of U.S. cases; commenting about cruise ship Grand Princess, he stated his preference that infected passengers not disembark as he did not want "to have the [U.S. case] numbers double because of one ship".[162] He cited the relatively low number of confirmed cases in the initial stages of the outbreak, as proof of success of his travel restriction on China.[162] Eventually in mid-March he rated his administration's response a score of 10/10.[163]

On March 11, 2020, Trump delivered an Oval Office address on national television, just hours after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, which caused a quick fall in financial markets. It was the second such address to the country of his presidency, the first being in January 2019, addressing illegal immigration. In his speech, Trump declared that the United States was "suspending all travel from Europe to the United States for the next 30 days", except travel from the United Kingdom, and including "the tremendous amount of trade and cargo" (post-speech, Trump said trade was still approved, while administration officials clarified that "American citizens or legal permanent residents or their families" were not affected). Trump also listed several economic policy proposals, and declared that insurance companies "have agreed to waive all co-payments for coronavirus treatments" (post-speech, America's Health Insurance Plans clarified the waivers were only for tests, not treatments). Trump praised his administration's response to the "foreign" virus while blaming the European Union, stating that "a large number of new clusters in the United States were seeded by travelers from Europe".[164]

On March 16, Trump changed his tone on the outbreak to a somber one. For the first time, he acknowledged that COVID-19 was "not under control", the situation was "bad" with months of impending disruption to daily lives, and a recession might occur.[165] Also on March 16, President Trump and the Coronavirus Task Force released new recommendations based on CDC guidelines for Americans, titled "15 Days to Slow the Spread".[166][167] On March 17, "I felt it was a pandemic long before it was called a pandemic."[168] He also said America will achieve total victory against the "invisible enemy", and called Americans to sacrifice together.[151]

On March 16, Trump began referring to COVID-19 as the "Chinese virus", and as a result he was criticized by Chinese and WHO officials for creating a potential stigma against Chinese and Asians. Trump disagreed with the criticism, and said that "China tried to say at one point—maybe they stopped—that it was caused by American soldiers. That can't happen."[169][170] Trump stopped using the term on March 23, citing the possibility of "nasty language" towards Asian-Americans.[171] On March 26, President Trump spoke on the phone with China's President Xi Jinping, when they pledged to cooperate in fighting against the pandemic. It signaled a fresh detente between the two countries after weeks of rising tensions.[172] Trump described their conversation:

Just finished a very good conversation with President Xi of China. Discussed in great detail the Coronavirus that is ravaging large parts of our Planet. China has been through much and has developed a strong understanding of the Virus. We are working closely together. Much respect![172]

On the same day, after a video call summit with the other G20 leaders, Trump stated the United States was working with international allies to stop the spread of the coronavirus and to increase rapid information and data sharing.[173]

After learning about a French clinical study which showed a 70% cure rate in 20 patients,[174][175] Trump promoted the drugs chloroquine (also known as chloroquine phosphate)[176] and hydroxychloroquine as potential treatments for COVID-19 on March 19. He noted the drugs showed "tremendous promise" and said he was working together with Governor Cuomo to begin quickly studying and treating coronavirus patients with the drugs in New York. He also remarked on their long-term usage as medicines in the United States saying, "the nice part is, it's been around for a long time, so we know that if it—if things don't go as planned, it's not going to kill anybody."[177][103] Fatal overdoses of these drugs have occurred, and potential side effects are also known.[178] Also during the briefing, Trump falsely claimed that chloroquine had already been "approved very, very quickly" by the Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for COVID-19 (leading to the FDA stating it had not yet approved any COVID-19 treatments).[179]

Within days of this briefing, a shortage occurred for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the United States, while panic-buying occurred overseas in Africa and South Asia.[180][181] In the state of Arizona, a man died, with his wife in critical condition, after they ingested fish bowl cleaner, which contained chloroquine phosphate. The couple believed the chemical cleaner could prevent them from contracting COVID-19, although the chloroquine phosphate in fish bowl cleaners is not the same formulation found in the medicines chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine.[182] The woman said she'd watched Trump's briefing in which she believed he promoted chloroquine as "basically pretty much a cure".[183] During the same briefing, Trump also discussed remdesivir as another promising COVID-19 therapy.[103]

On March 22, Trump indicated that he was considering scaling back social distancing measures implemented around a week ago: "We cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself". A day later, Trump argued that economic problems arising from social distancing measures will cause "suicides by the thousands" (without citing evidence) and "probably more death" than COVID-19 itself. He declared that the United States would "soon, be open for business", in a matter of weeks.[184][185] On March 24, Trump expressed a target of lifting restrictions "if it's good" by April 12, the Easter holiday, for "packed churches all over our country".[186] However, a survey of prominent economists by the University of Chicago indicated abandoning an economic lock-down prematurely would do more economic damage than maintaining it.[187] Later on March 29, 2020, Trump expressed to maintain social distancing until April 30, 2020.[188]

On March 28, Trump raised the possibility of placing a two-week enforceable quarantine on New York, New Jersey, and "certain parts of Connecticut" in order to prevent travel from those places to Florida.[189] The federal quarantine power is limited to preventing people reasonably believed to be infected with a communicable disease from entering the country or crossing state lines.[190] Later that day, following criticism from the three governors, Trump withdrew the quarantine proposal. Instead, the CDC issued a travel advisory advising residents of the three states to "refrain from non-essential domestic travel for 14 days effective immediately".[191]

Administration officials

During the early stages of the outbreak, Trump administration officials gave mixed assessments of the seriousness and scale of the COVID-19 outbreak. CDC Director Robert Redfield said in late January that "the immediate risk to the American public is low", then in late February stated it would be "prudent to assume this pathogen will be with us for some time to come". While federal economic policy chief Larry Kudlow was declaring the COVID-19 spread being contained "pretty close to airtight" in late February, Nancy Messonnier (head of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases) and Anthony Fauci (head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) warned of the impending community spread of the virus in the United States, with Messonnier stating: "Disruption to everyday life might be severe". Around this point, Stephen Hahn, the head of the FDA, warned of national medical supplies being disrupted due to the outbreak. Later in early March, the U.S. Surgeon General, Jerome Adams, declared that "this is likely going to get worse before it gets better".[192] In March, while giving public briefings from the White House addressing the pandemic, many administration officials and health experts took time to thank Trump for his leadership, as he watched nearby.[107]

In February 2020, the CDC was notifying the press that it was expecting the infections to spread, and urged local governments, businesses, and schools to develop plans for the outbreak. Among the suggested preparations were canceling mass gatherings, switching to teleworking, and planning for continued business operations in the face of increased absenteeism or disrupted supply chains.[193]

CDC officials warned that widespread transmission may force large numbers of people to seek hospitalization and other healthcare, which may overload healthcare systems.[16] Public health officials stressed that local governments would need assistance from the federal government if there were school and business closures.[78]

On March 23, Surgeon General Jerome Adams made several media appearances, in which he endorsed social distancing measures and warned the country: "This week, it's going to get bad ... we really, really need everyone to stay at home [...] Every single second counts. And right now, there are not enough people out there who are taking this seriously."[194]

State, territorial, and local response

U.S. military response

After mid-March 2020, the Federal government made a major move to use the U.S. military to initiate and lead an effort to rapidly grow COVID-19 intensive care facilities nationwide.[citation needed]

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), under existing statutory authority that comes from authorizations and powers of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), will be rapidly leasing a large number of buildings nationwide in hotels and in larger open buildings to immediately grow the number of rooms and beds with ICU capability for patients of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. A public briefing of the plan was given by Army General Todd Semonite on March 20, 2020. USACE will handle leasing and engineering, with contracts for rapid facility modification and setup issued to local contractors. The plan envisions that the operation of the facilities and the provision of medical staff would be entirely handled by the various U.S. states rather than the Federal government.[19] One of the early and largest buildings to be converted is the Javits convention center in New York City, which was quickly being transformed into a 2000-bed care facility on March 23, 2020.[195]

In addition to the many popup hospitals nationwide, the United States Navy prepared to deploy two hospital ships, USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort, on March 18 to assist potentially overwhelmed counties with acute patient care.[67] Trump said the ships were getting ready to go to New York, on the request of Governor Cuomo, and that the Comfort would be deployed from San Diego to somewhere on the West Coast.[151] On March 22, Trump announced that the Comfort will go to the East Coast and the Mercy will go to the West Coast. He also said the government may be using cruise ships.[155] The USNS Comfort was scheduled to set sail from Virginia on March 28 and arrive in New York City in two days.[196]

Economic impact

Economic analysts revised their forecasts downward going into March, with Goldman Sachs estimating on March 20 that the economy could contract by as much as 24% during the second quarter of 2020, following their 5% decline estimate just four days earlier. Some analysts estimated a recession had already begun.[197][198][199][200][201][excessive citations]

Domestic travel

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In mid-March, most major American and foreign airlines began cutting back on domestic and international flights as a result of the sudden drop in travel demand from the pandemic and subsequent travel bans. They have phased out routes and were making frequent schedule updates.[202][203]

The outbreak produced occasional disruptions to air traffic control with area control centers in New York and Indianapolis, and airport towers at Midway International Airport in Chicago and McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas evacuated for sterilization after at least one person who had been in each tested positive for COVID-19.[204]

On March 14, Amtrak reduced its service between Washington and Boston as the COVID-19 outbreak drastically decreased travel demand. It faced steep revenue losses during the crisis. It also asked noncritical employees "to take time off on an unpaid basis".[205] By the following week, New York's subways, usually the nation's busiest, were running mostly empty, which had the Metropolitan Transportation Authority using $1 billion from its line of credit to stay afloat.[206]

The lobbying group for the airline industry, Airlines for America (A4A), on March 16 called for a $50 billion subsidy, including $4 billion for cargo services.[207] CNBC reports that airlines are preparing for a ban on domestic flights after President Trump said on March 14 that he is considering travel curbs and acting DHS Secretary Chad Wolf said all options remained on the table when asked about a possible ban, the first since September 11, 2001. United Airlines said they expected a drop of $1.5 billion in March revenue, American Airlines said they expected to decrease domestic capacity by 20% in April and 30% in May, and Delta Air Lines told employees it would cut capacity by 40%.[208]

Several of the largest mass transit operators in the U.S. have reduced service in response to lower demand caused by work from home policies and self-quarantines. The loss of fares and sales tax, a common source of operating revenue, is predicted to cause long-term effects on transit expansion and maintenance.[209] The American Public Transportation Association issued a request for $13 billion in emergency funding from the federal government to cover lost revenue and other expenses incurred by the pandemic.[210] Many localities reported an increase in bicycling as residents sought socially distant means of getting around.[211][212]

Financial market impacts

On February 27, 2020, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) dropped 1,191 points, the largest single-day point drop in the index's history at the time; some attributed the drop to anxiety about the epidemic.[213] The same day, the S&P 500 logged a 4.4% decline.[214] Since then, the record has been beaten five more times during the outbreak on March 9 (−2,013), March 11 (−1,465), March 12 (−2,353), and finally setting the current record for most points lost in a single day by losing 2,997 points on March 16. It once again fell another 1,338 points on March 18. On March 13, the stock market rebounded for the single largest one-day point gain in the market's history by gaining 1,985 points after Trump declared a state of national emergency to free up resources to combat the virus.[215][216] The six business days it took for the S&P 500 Index to drop 10% (from February 20 to 27) "marked the quickest 10% decline from an all-time high in the index's history".[214] From January 21 to March 1, the DJIA dropped more than 3,500 points, equating to roughly a 13% decrease.[217][218]

Stock index futures declined sharply during Trump's March 11 address,[219] and the Dow Jones declined 10% the following day—the largest daily decline since Black Monday in 1987—despite the Federal Reserve also announcing it would inject $1.5 trillion into money markets.[220]

By March 18, investors were shunning even assets considered safe havens during economic crises, such as government bonds and gold, moving into cash positions.[221] By March 20, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was below the level when President Trump was inaugurated on January 20, 2017, having fallen 35% from its February peak.[222]

The markets rallied between March 23 and 26, with the Dow having its best three-day gain since 1931. On March 27, the Dow fell 3.5% and the S&P 500 fell 3.2%. The Nasdaq Index also fell. Boeing fell 10%, while Exxon and Disney each fell 6%.[223]

Employment effects

The number of persons filing for unemployment insurance increased from 211,000 the week ending March 7, to 281,000 for the week ending March 14, an increase of 70,000 or 33%, the largest percent increase since 1992.[224] Just part way through the following week, 15 states had reported nearly 630,000 claims.[225][226] Goldman Sachs forecast that more than two million people would file the week of March 21, an unprecedented number.[227] Goldman also forecast that the unemployment rate could rise towards nine percent over the second and third quarters, with much depending on the specifics of government stimulus plans.[228] On March 26, the Labor Department reported that there were a record number of unemployment claims, surging to 3.28 million. This was higher than the Financial Crisis of 2009 which peaked at 665,000 and the all time high of 695,000 that was recorded in October 1982.[229]

Restaurant industry

The 2019–2020 coronavirus pandemic impacted the restaurant industry worldwide via government closures, resulting in layoffs of workers and loss of income for restaurants and owners.[citation needed]

The U.S. restaurant industry was projected to have $899 billion in sales for 2020 by the National Restaurant Association, the main trade association for the industry in the United States.[230] The industry as a whole as of February 2020 employed more than 15 million people, representing 10% of the workforce directly.[230] It indirectly employed close to another 10% when dependent businesses such as food producers, trucking, and delivery services were factored in, according to Ohio restaurateur Britney Ruby Miller.[230]

On March 15, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and Ohio Health Department director Amy Acton ordered the closure of all bars and restaurants to help slow the spread of the virus, saying the government "encouraged restaurants to offer carryout or delivery service, but they would not be allowed to have people congregating in the businesses."[231][230][232] The next day, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, and Maryland followed suit.[231][233]

Groups of restaurateurs in New York City and Cincinnati called on governments to provide help to the nation's small and independent restaurants.[234][230] On March 19 the New York group called for state governments to issue orders for rent abatements, suspension of sales and payroll taxes, and a full shutdown so business interruption insurance coverage would be triggered.[235] On March 20 the Cincinnati group called on the federal government to provide a $225 billion bailout to the restaurant industry.[230]

Several restaurant chains altered their operating procedures to prevent the spread of the virus, including removing seating, restricting the use of condiments, and switching to mobile payment systems. Many restaurants opted to close their dining rooms and instead switch to solely take-out food service to comply with physical distancing recommendations.[236]

Retail

A number of retailers, particularly grocery stores, reduced their opening hours to allow additional time to restock and deep-clean their stores.[237] Major stores such as Walmart, Apple, Nike, Albertson's, and Trader Joe's also shortened their hours.[238][239] Some grocery store chains, including Stop & Shop and Dollar General, devoted a portion of their operating hours to serve only senior citizens.[240][241] Many grocery stores and pharmacies began installing plexiglass sneeze guards at register areas to protect cashiers and pharmacists, and adding markers six feet apart at checkout lines to encourage customers to maintain physical distance.[242] To prevent hoarding, many supermarkets and retailers placed limits on certain products such as toilet paper, hand sanitizer, over-the-counter medication, and cleaning supplies.[243] However, the Food Marketing Institute announced that its supply chain was not strained and all products would be available in the future.[243] Major retail chains started hiring tens of thousands of employees to keep up with demand, including Walmart (150,000), CVS Pharmacy (50,000), Dollar General (50,000), and 7 Eleven (20,000).[244] A daily senior shopping hour, checkout line distancing markers, hand washing and sanitizer for employees, disinfecting wipes for customers to use on carts, and a ban on reusable bags became mandatory in Massachusetts on March 25.[245]

Shipping facilities

Since consumers were increasingly relying on online retailers, Amazon planned to hire another 100,000 warehouse and delivery workers and raise wages $2 per hour through April. They also reported shortages of certain household staples.[246]

A March 21 article in the Chicago Tribune reported that employees at UPS, FedEx, and XPO often have been pressured not to take time off, even with symptoms such as fever and cough consistent with Coronavirus. Public health authorities state that the risk is relatively low to customers receiving packages, in part because Coronavirus does not live for very long on cardboard, but it most certainly is a danger for employees on crowded conveyor belts.[247]

At its warehouses, Amazon has stopped exit screenings, as well as group meetings at the beginning of shifts, and has staggered shift times and break times. The company also announced it would provide up to two weeks of pay to all employees diagnosed with coronavirus or placed into quarantine, but presumably not for employees who merely have symptoms of fever and cough.[248]

Production of emergency supplies

In response to shortages, some alcoholic beverage facilities started manufacturing and distributing alcohol-based hand sanitizer.[249] General Motors opened its manufacturing, logistics, and purchasing infrastructure for use by Ventec, a manufacturer of medical ventilators.[250] As medical mask manufacturers hired hundreds of new workers and increased output,[251] in response to urgent requests from hospital workers, volunteers with home sewing machines started producing thousands of non-medical masks that can be sterilized and re-used. Fabric was bought privately or donated by Joann Fabrics.[252] The CDC recommended the use of homemade masks (preferably in combination with a full-face splash shield) only as a "last resort" when no other respiratory protective technologies were available, including reused professional masks.[253]

Other financial effects

In February 2020, the American companies Apple Inc. and Microsoft began lowering expectations for revenue because of supply chain disruptions in China caused by the virus.[254] In a February 27 note to clients, Goldman Sachs said it expects no earnings growth for U.S. companies in 2020 as a result of the virus, at a time when the consensus forecast of Wall Street expected "earnings to climb 7%".[255] On March 20, 2020 as part of an SEC filing, AT&T cancelled all stock buyback plans included a plan to repurchase stock worth $4 billion during the second quarter. The reasons AT&T gave for the cancellation was to invest the money into its networks and in taking care of its employees during the pandemic.[256]

The pandemic, along with the resultant stock market crash and other impacts, has led to increased discussion of a recession in the United States.[257] Experts differ on whether a recession will actually take place, with some saying it's not inevitable while others say the country may already be in a recession.[257][258] Of the economists surveyed in March by the University of Chicago at multiple U.S. universities, 51% agreed or strongly agreed there would be a "major" recession caused by COVID-19, while 31% were uncertain or disagreed.[259]

In response to the economic damage caused by the pandemic, some economists have advocated for financial support from the government for individual Americans and for banks and businesses.[260][261] Others have objected to intervention by the government on the grounds that it would alter the role of the Federal Reserve and enshrine moral hazard as a defining market principle.[262]

Telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a sharp increase in the utilization of telemedical services in the United States, specifically for COVID-19 screening and triage.[263][264] On March 26, 2020, GoodRx launched a telemedicine price comparison platform[265] that lists the prices of COVID-19 assessments by telemedicine provider and state.[263] As of March 29, 2020[update], three companies are offering free telemedical screenings for COVID-19 in the United States: K Health (routed through an AI chatbot), Ro (routed through an AI chatbot), and GoodRx (offered through its HeyDoctor platform).[265][266][264][267]

Timing of removing economic lockdowns

On March 24, Trump expressed a target of lifting restrictions "if it's good" by April 12, the Easter holiday, for "packed churches all over our country".[268] However, a survey of prominent economists by the University of Chicago indicated abandoning an economic lock-down prematurely would do more economic damage than maintaining it.[187] The New York Times reported on March 24 that: "There is, however, a widespread consensus among economists and public health experts that lifting the restrictions would impose huge costs in additional lives lost to the virus — and deliver little lasting benefit to the economy."[269] Bill Gates said: “It’s very tough to say to people, ‘Hey keep going to restaurants, go buy new houses, ignore that pile of bodies over in the corner, we want you to keep spending because there’s some politician that thinks GDP growth is what counts...It’s hard to tell people during an epidemic...that they should go about things knowing their activity is spreading this disease.”[270]

Criticism of proposed remedies

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says Congress is not set-up to send out checks now (to individuals) and then if the crisis goes on another four weeks, or six weeks, to send out a second batch of checks. He states the U.S. economy was not in great shape to begin with, for example, with overall growth for March 2020 expected to be less than 2%. The main problem will be that people can't go to work because of fear of the virus. And regarding a welfare safety net, he writes, "America has the weakest social protection of almost any of the advanced countries and so we're having to patch in a kind of social protection system on the fly and it's going to be really hard and that means the recovery is going to be very difficult."[271]

Social impacts

In order to minimize the spread of infection, public health officials and political figures have initiated steps to isolate infected patients, impose quarantines, and recommend or require physical distancing during group activities, including the closing of schools, retail stores, workplaces, sports events, and leisure activities such as dining and movies.

Lockdowns

In extreme instances, a number of cities and states have imposed lockdown measures which limit where people can travel, work and shop away from their homes:

- California. The Governor has ordered everyone to stay at home except to get food, care for a relative or friend, obtain health care, or go to an "essential job". People working in critical infrastructure sectors may continue to go to their jobs, but should try to keep at least six feet apart from anyone else. Indoor restaurants, bars and nightclubs, entertainment venues, gyms and fitness studios are closed, although some restaurants can still provide take-out meals. Gas stations, pharmacies, grocery stores, convenience stores, banks and laundry services remain open.[64]

- New York. Non-essential businesses must shut down their in-office personnel functions, with the exception of financial institutions, retailers, pharmacies, hospitals, news media, manufacturing plants and transportation companies, among others. Casinos, gyms, theaters, shopping malls, amusement parks and bowling alleys are to be closed. "Non-essential gatherings" of any size and for any reason are temporarily banned, and in public, people must keep at least six feet away from each other. Residents 70 and older and people with compromised immune systems or underlying illnesses must remain indoors (unless exercising outside), wear a mask in the company of others and prescreen visitors by taking their temperature.[64]

Similar restrictions to varying degree have been imposed in Illinois, Texas, Nevada, New Jersey and Florida, including the shutting down of hotels.[272]

| States with a lockdown order or advisory[273] | |

|---|---|

| State | Date enacted |

| California | March 19, 2020 |

| Colorado | March 26, 2020 |

| Connecticut | March 23, 2020 |

| Delaware | March 24, 2020 |

| Hawaii | March 25, 2020 |

| Idaho | March 25, 2020 |

| Illinois | March 21, 2020 |

| Indiana | March 24, 2020 |

| Kansas | March 30, 2020 |

| Kentucky[f] | March 26, 2020 |

| Louisiana | March 23, 2020 |

| Massachusetts[f] | March 24, 2020 |

| Michigan | March 24, 2020 |

| Minnesota | March 27, 2020 |

| Montana | March 28, 2020 |

| New Hampshire[274] | March 27, 2020 |

| New Jersey | March 21, 2020 |

| New Mexico | March 24, 2020 |

| New York | March 22, 2020 |

| North Carolina | March 30, 2020 |

| Ohio | March 23, 2020 |

| Oregon | March 23, 2020 |

| Vermont | March 25, 2020 |

| Washington | March 23, 2020 |

| West Virginia | March 24, 2020 |

| Wisconsin | March 25, 2020 |

Educational impacts

As of March 24, 2020[update], 124,000 public and private schools had closed nationwide, affecting at least 55 million students, with most schools in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all five inhabited territories closed statewide.[275] To ensure food-insecure students continued to receive lunches while schools were closed, many states and school districts arranged for "grab-and-go" lunch bags or used school bus routes to deliver meals to children.[276] To provide legal authority for such efforts, the U.S. Department of Agriculture waived several school lunch program requirements.[277]

A large number of higher educational institutions canceled classes and closed dormitories in response to the outbreak, including all members of the Ivy League,[278] and many other public and private universities across the country.[279]

Due to the disruption to the academic year caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Department of Education approved a waiver process, allowing states to opt-out of standardized testing required under the Every Student Succeeds Act.[280] In addition, the College Board eliminated traditional face-to-face Advanced Placement exams in favor of an online exam that can be taken at home.[281] The College Board also cancelled SAT testing in March and May in response to the pandemic.[282] Similarly, April ACT exams were rescheduled for June 2020.[283]

The Department of Education also authorized limited student loan relief, allowing borrowers to suspend payments for at least two months without accrueing interest.[280]

Prison impacts

As COVID-19 was spreading to several prisons in the U.S., some states and local jurisdictions began to release prisoners considered vulnerable to the virus.[284]

Xenophobia and racism

They're amazing people and the spreading of the virus is not their fault in any way shape or form. They're working closely with us to get rid of it ... It's very important that we totally protect our Asian-American community in the United States and all around the world.

There have been widespread incidents of xenophobia and racism against Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans.[285] It had been reported that Asian Americans had been purchasing firearms in response to the xenophobia arising from the pandemic.[286] The FBI issued an alert that neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups were encouraging members to, if they contract it, spread the virus via "bodily fluids and personal interactions" with Jews and police officers.[287]

Media Matters for America accused Fox News Channel personalities and guests of racism for repeatedly using terms such as "Chinese virus" and "Wuhan virus" on-air.[288]

Event cancellations

As "social distancing" entered the public lexicon, emergency management leaders encouraged the cancellation of large gatherings to slow the rate of infection.[citation needed] Technology conferences such as Apple Inc.'s Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC),[290] E3 2020,[291] Facebook F8, Google I/O and Cloud Next,[292] and Microsoft's MVP Summit[293][294] have been either cancelled or have replaced in-person events with internet streaming events.

On February 21, Verizon pulled out of an RSA conference, joining the ranks of AT&T Cybersecurity and IBM.[295] On February 29, the American Physical Society cancelled its annual March Meeting, scheduled for March 2–6 in Denver, Colorado, even though many of the more than 11,000 physicist participants had already arrived and participated in the day's pre-conference events.[296] On March 6, the annual South by Southwest (SXSW) conference and festival scheduled to run from March 13 to 22 in Austin, Texas, were cancelled following after the city government declared a "local disaster" and ordered conferences to shut down for the first time in 34 years.[297][298] The cancellation is not covered by insurance.[299][300] In 2019, 73,716 people attended the conferences and festivals, directly spending $200 million and ultimately boosting the local economy by $356 million, or four percent of the annual revenue of the region's hospitality and tourism economic sectors.[301][302]

After the cancellations of the Ultra Music Festival in Miami and SXSW in Austin, speculation began to grow about the Coachella festival set to begin on April 10 in the desert in Indio, California.[303][304] The annual festival, which has attracted some 125,000 people over two consecutive weekends, is insured only in the event of a force majeure cancellation such as one ordered by local or state government officials. Estimates on an insurance payout range from $150 million to $200 million.[305] On March 10, event organizers announced the festival had been postponed to October.[citation needed]

Media

Publishing

The scale of the COVID-19 outbreak has prompted several major publishers to temporarily disable their paywalls on related articles, including Bloomberg News, The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Seattle Times.[306][307]

Several alt weekly newspapers in affected metropolitan areas, including The Stranger in Seattle and Austin Chronicle, have announced layoffs and funding drives due to lost revenue. Public events and venues accounted for a majority of revenue for alt-weekly newspapers, which was disrupted by the cancellation of large public gatherings.[307][308]

Film

Most U.S. cinema chains, where allowed to continue operating, reduced the seating capacity of each show time by half to minimize the risk of spreading the virus between patrons.[309] Audience limits, as well as mandatory and voluntary closure of cinemas in some areas, led to a total North American box office sales the lowest since October 1998.[310] On March 16, numerous theater chains temporarily closed their locations nationwide.[311] A number of Hollywood film companies have suspended production and delayed the release of some films.[312][313]

Television

In March, a number of studio-based talk shows and game shows announced plans to film behind closed doors with no audience.[314] Some television networks and news channels have adjusted their programming to incorporate coverage of the pandemic and adhere to CDC guidelines, including encouraging remote work and physical distancing on-air (including separation between on-air anchors and increased use of remote interviews).[315][316][317]

Quarantine and remote work efforts, as well as interest in updates on the pandemic, have resulted in a larger potential audience for television broadcasters, especially news channels. Nielsen estimated that by March 11, television usage had increased by 22% week-over-week. It was expected that streaming services would see an increase in usage, while potential economic downturns associated with the pandemic could accelerate the market trend of cord cutting.[318][319][320] WarnerMedia reported that HBO Now saw a spike in usage, and the most viewed titles included documentary Ebola: The Doctors' Story and the 2011 film Contagion for their resonance with the pandemic.[321]

Sports

A suspension of games for various time periods were announced by almost all professional sports leagues in the United States on March 11 and 12, including the National Basketball Association (which had a player announced as having tested positive),[322]National Hockey League,[323] Major League Baseball,[324] and Major League Soccer.[325][326] College athletics competitions were similarly cancelled by schools, conferences and the NCAA—which cancelled all remaining championships for the academic year on March 12. This also resulted in the first-ever cancellation of the NCAA's popular "March Madness" men's basketball tournament (which had been scheduled to begin the following week) in its 81-year history.[322][327][328]

The 2020 Indian Wells Masters tennis tournaments were cancelled on March 10.[329] The ATP Tour and WTA Tour have both suspended competition until late-April, which has also led to the cancellation of the Miami Open.[330] NASCAR on March 13 postponed the races at Atlanta Motor Speedway and announced on March 16 that it will postpone all race events until May 3.[331] The IndyCar Series similarly announced the cancellation of all races through the end of April.[332]

The PGA Tour played the first round of the 2020 Players Championship on March 12, and stated that subsequent rounds and tournaments would be held without spectators,[333] but later cancelled the rest of the tournament and subsequent events through early-May.[334][335] The LPGA Tour similarly cancelled all events through April.[334][336] Two men's majors, the Masters and PGA Championship, were postponed.[337][334]

Religious services

The response from American churches has been mixed. Some churches have suspended services, others have moved to online services, while still others continue their regular services. Some state orders against large gatherings, such as in Ohio and New York, specifically exempt religious organizations.[338] Colorado Springs Fellowship Church insists it has a constitutional right to defy a state closure order.[339] Evangelical college Liberty University of Lynchburg, Virginia, moved its classes online but called its 5,000 back to campus despite Governor Ralph Northam's (D) order to close all non-essential businesses.[340]

By March 20, every Roman Catholic diocese in the United States had suspended the public celebration of Mass and dispensed with the obligation to attend Sunday Mass, as had the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the United States also suspended public Divine Liturgies.[341][342][343][344][345]

On March 24, President Trump said, in regard to Easter (April 12), "Wouldn't it be great to have all the churches full? You'll have packed churches all over our country. I think it'll be a beautiful time." As of March 25, many churches were not prepared to risk reopening, and most churches were predicted to remain closed on Easter.[346]

Forty-three members of the Life Church in Glenview, Illinois are sick and ten have been tested positive for Covid-19. The infections began after a service on March 15, the same day people were warned by the state government against large gatherings, but before the official edict.[347]

Public response

Opinion polling showed a significant partisan divide regarding the outbreak.[348] NPR, PBS NewsHour and Marist found in their mid-March survey that 76% of Democrats viewed COVID-19 as "a real threat", while only 40% of Republicans agreed; the previous month's figures for Democrats and Republicans were 70% and 72% respectively.[349] A mid-March poll conducted by NBC News and The Wall Street Journal found that 60% of Democrats were concerned someone in their family might contract the virus, while 40% of Republicans expressed concern. Nearly 80% of Democrats believed the worst was yet to come, whereas 40% of Republicans thought so. About 56% of Democrats believed their lives would change in a major way due to the outbreak, compared to 26% for Republicans.[350] A mid-March poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 83% of Democrats had taken certain precautions against the virus, compared to 53% of Republicans. The poll found that President Trump was the least-trusted source of information about the outbreak, at 46% overall, although 88% of Republicans expressed trust in the president, second only to their trust in the CDC.[351]

Background and preparations

The United States has experienced pandemics and epidemics throughout its history, including the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian flu, and the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemics.[352][353][354] In the most recent pandemic prior to COVID-19, the 2009 H1N1 swine flu took the lives of more than 12,000 Americans and hospitalized another 200,000.[355][356][352] Because of this pandemic and the 2014 Ebola epidemic, which saw only a small number of Americans infected,[357] the Obama Administration increased planning and analysis that focused on deficiencies in the government's response to outbreaks.[356] In 2017, outgoing Obama administration officials briefed incoming Trump administration officials on how to respond to pandemics by using simulated scenarios, although by the time of the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S., around two-thirds of Trump administration officials at the briefing had left the administration.[356]

The United States Intelligence Community, in its annual worldwide threat assessment reports of 2017 and 2018, stated new types of microbes that are "easily transmissible between humans" remained "a major threat". Similarly, for the 2019 worldwide threat assessment, the U.S. intelligence agencies warned that "the United States and the world will remain vulnerable to the next flu pandemic or large-scale outbreak of a contagious disease that could lead to massive rates of death and disability, severely affect the world economy, strain international resources, and increase calls on the United States for support."[358][359]

Citing lessons learned from the swine flu pandemic, Ebola outbreak, and the 2001 anthrax attacks, President Trump released a National Biodefense Strategy on September 18, 2018 in response to a Congressional directive.[360][361][362][363] According to Trump, the new strategy was designed to strengthen the nation's defenses against disease outbreaks and bioterrorism and to make responses to them more efficient and better coordinated.[360][361] Concurrently, he released a National Security Presidential Memorandum that appointed the Secretary of HHS Alex Azar to oversee implementation of the government's new biodefense strategy and directed National Security Advisor John Bolton to assist in reviewing and improving the nation's biodefenses.[364][365][360] At a time when multiple agencies and departments shared responsibility for biodefense,[363] Bolton and Azar claimed this centralization of primary authority for biodefense in the HHS would provide greater accountability.[366]