Jinn

Jinn (Template:Lang-ar, jinn), also Romanized as djinn or Anglicized as genies (with the more broad meaning of spirits or demons, depending on source),[1][2] are supernatural creatures in early pre-Islamic Arabian and later Islamic mythology and theology. Like humans, they are created with fitra, neither born as believers nor as unbelievers, but their attitude depends on whether or not they accept God's guidance.[3] Since jinn are neither innately evil nor innately good, Islam was able to adapt spirits from other religions during its expansion. Jinn are not a strictly Islamic concept; rather, they may represent several pagan beliefs integrated into Islam.[a][5]

In an Islamic context, the term jinn is used for both a collective designation for any supernatural creature and also to refer to a specific type of supernatural creature.[6] Therefore, jinn are often mentioned together with devils/demons (shayāṭīn). Both devils and jinn feature in folk lore and are held responsible for misfortune, possession and diseases. However, the jinn are sometimes supportive and benevolent. They are mentioned frequently in magical works throughout the Islamic world, to be summoned and bound to a sorcerer, but also in zoological treatises as animals with a subtle body.

Etymology

Jinn is an Arabic collective noun deriving from the Semitic root JNN (Template:Lang-ar, jann), whose primary meaning is "to hide" or "to conceal". Some authors interpret the word to mean, literally, "beings that are concealed from the senses".[7] Cognates include the Arabic majnūn ("possessed", or generally "insane"), jannah ("garden", also “heaven”), and janīn ("embryo").[8] Jinn is properly treated as a plural, with the singular being jinnī. [b]

The origin of the word Jinn remains uncertain.[2] Some scholars relate the Arabic term jinn to the Latin genius, as a result of syncretism during the reign of the Roman empire under Tiberius Augustus,[9] but this derivation is also disputed.[10] Another suggestion holds that jinn may be derived from Aramaic "ginnaya" (Template:Lang-syc) with the meaning of "tutelary deity",[11] or also "garden". Others claim a Persian origin of the word, in the form of the Avestic "Jaini", a wicked (female) spirit. Jaini were among various creatures in the possibly even pre-Zoroastrian mythology of peoples of Iran.[12][13]

The Anglicized form genie is a borrowing of the French génie, from the Latin genius, a guardian spirit of people and places in Roman religion. It first appeared[14] in 18th-century translations of the Thousand and One Nights from the French,[15] where it had been used owing to its rough similarity in sound and sense and further applies to benevolent intermediary spirits, in contrast to the malevolent spirits called demon and heavenly angels, in literature.[16] In Assyrian art, creatures ontologically between humans and divinities are also called genie.[17]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The exact origins of belief in jinn are not entirely clear.[19] Some scholars of the Middle East hold that they originated as malevolent spirits residing in deserts and unclean places, who often took the forms of animals;[19] others hold that they were originally pagan nature deities who gradually became marginalized as other deities took greater importance.[19] According to common Arabian belief, soothsayers, pre-Islamic philosophers, and poets were inspired by the jinn.[20][19] Jinn had been worshipped by many Arabs during the Pre-Islamic period,[20] but, unlike gods, jinn were not regarded as immortal. However, jinn were also feared and thought to be responsible for causing various diseases and mental illnesses.[21][19] Julius Wellhausen observed that such spirits were thought to inhabit desolate, dingy, and dark places and that they were feared.[22] One had to protect oneself from them, but they were not the objects of a true cult.[22] Some scholars argue that angels and demons were introduced by Muhammad to Arabia and did not existed among the jinn. On the other hand, Amira El-Zein argues that angels were known to the pagan Arabs, but the term jinn was used for all kinds of supernatural entities among various religions and cults; thus, Zoroastrian, Christian, and Jewish angels and demons were conflated with "jinn".[20] Al-Jahiz credits the pre-Islamic Arabs with believing that the society of jinn constitutes of several tribes and groups and some natural events were attributed to them, such as storms. They also thought jinn could protect, marry, kidnap, possess and kill people.[23]

Islamic theology

In scripture

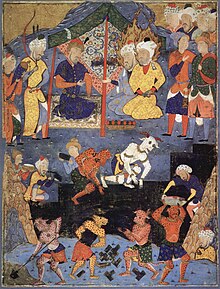

Jinn are mentioned approximately 29 times in the Quran.[24] In Islamic tradition, Muhammad was sent as a prophet to both human and jinn communities, and that prophets and messengers were sent to both communities.[25][26] Traditionally Surah 72, named after them (Al-Jinn), is held to tell about the revelation to jinn and several stories mention one of Muhammad's followers accompanied him, witnessing the revelation to the jinn.[27] They appear with different attitudes.[28] In the story of Solomon they appear as nature spirits comparable to Talmudic shedim. Solomon was gifted by God to talk to animals and spirits. God granted him authority over the rebellious jinn and devils forcing them to build the First Temple. In other instances, the Quran tells about Pagan Arabs, calling jinn for help, instead of God. The Quran reduced the status of jinn from that of tutelary deities to that of minor spirits, usually paralleling humans.[29] In this regard, the jinn appear often paired with humans. To assert a strict monotheism and the Islamic concept of Tauhid, all affinities between the jinn and God were denied, thus jinn were placed parallel to humans, also subject to God's judgment and afterlife. They are also mentioned in collections of canonical hadiths. One hadith divides them into three groups, with one type flying through the air; another that are snakes and dogs; and a third that moves from place to place like human.[30]

Exegesis

Belief in jinn is not included among the six articles of Islamic faith, as belief in angels is, however at least some Muslim scholars believe it essential to the Islamic faith.[31][32] In Quranic interpretation, the term jinn can be used in two different ways:

- As invisible entities, who roamed the earth before Adam, created by God out of a "mixture of fire" or "smokeless fire" (marijin min nar). They are believed to resemble humans in that they eat and drink, have children and die, are subject to judgment, so will either be sent to heaven or hell according to their deeds.[33] But they were much faster and stronger than humans.[34] This jinn are distinct from an angelic tribe called Al-jinn, named after Jannah (the Gardens), heavenly creatures created out of the fires of samum in contrast to the genus of jinn created out of mixture of fire, who waged war against the genus of jinn and regarded as able to sin, unlike their light created counterpart.[35][36]

- As the opposite of al-Ins (something in shape) referring to any object that cannot be detected by human sensory organs, including angels, demons and the interior of human beings. Accordingly, every demon and every angel is also a jinn, but not every jinn is an angel or a demon.[37][38][39][40] Al-Jahiz categorizes the jinn in his work Kitab al-Hayawan as follows: If he is pure, clean, untouched by any defilement, being entirely good, he is an angel, if he is faithless, dishonest, hostile, wicked, he is demon, if he succeeds in supporting an edifice, lifting a heavy weight and listening at the doors of Heaven he is a marid and if he more than this, he is an ifrit.[41]

Related to common traditions, the angels were created on Wednesday, the jinn on Thursday and humans on Friday, but not the very next day, rather more than 1000 years later, respectively.[42] The community of the jinn race were like those of humans, but then corruption and injustice among them increased and all warnings sent by God were ignored. Consequently, God sent his angels to battle the infidel jinn. Just a few survived, and were ousted to far islands or to the mountains. With the revelation of Islam, the jinn were given a new chance to access salvation.[30][43][44] But because of their prior creation, the jinn would attribute themselves to a superiority over humans and envy them for their place and rank on earth.[45]

Jinn belief

Classical era

Although the Quran reduced the status of jinn from that of tutelary deities to merely spirits, placed parallel to humans, subject to God's judgment and the process of life, death and afterlife, they were not consequently equated with demons.[46] When Islam spread outside of Arabia, belief in the jinn was assimilated with local belief about spirits and deities from Iran, Africa, Turkey and India.[47]

Early Persian translations of the Quran identified the jinn either with peris or divs[30] depending on their moral behavior. However, such identifications of jinn with spirits of another culture are not universal. Some of the pre-Islamic spirits remained. Peris and divs are frequently attested as distinct from jinn among Muslim lore,[48] but since both div as well as jinn are associated with demonic possession and the ability to transform themselves, they overlap sometimes.[49]

Especially Morocco has many possession traditions, including exorcism rituals,[50] despite the fact, jinn's ability to possess humans is not mentioned in canonical Islamic scriptures directly.

In Sindh the concept of the jinni was introduced when Islam became acceptable and "Jinn" has become a common part of local folklore, also including stories of both male jinn called "jinn" and female jinn called "Jiniri". Folk stories of female jinn include stories such as the Jejhal Jiniri. Although, due to the cultural influence, the concept of jinn may vary, all share some common features. The jinn are believed to live in societies resembling these of humans, practicing religion (including Islam, Christianity and Judaism), having emotions, needing to eat and drink, and can procreate and raise families. Additionally, they fear iron, generally appear in desolate or abandoned places, and are stronger and faster than humans.[30] Since the jinn share the earth with humans, Muslims are often cautious not to accidently hurt an innocent jinn by uttering "destur" (permission), before sprawling hot water.[30][51][52] Generally, jinn are thought to eat bones and prefer rotten flesh over fresh flesh.[53]

In Mughal or Urdu cultures Jinn often appear to be obese characters and refer to their masters as "Aqa".

In later Albanian lore, jinn (Xhindi) live either on earth or under the surface and may possess people who have insulted them, for example if their children are trodden upon or hot water thrown on them.[54]

The concept of Jinn was also prevalent in Ottoman society and much about their beliefs have yet to be known.

In Turkic lore, jinn (Template:Lang-tr) are often paired with in, another demonic entity, sharing many characteristics with the jinn.[55]

The composition and existence of jinn is the subject of various debates during the Middle Ages. According to Al-Shafi’i (founder of Shafi‘i schools), the invisibility of jinn is so certain that anyone who thinks they have seen one is ineligible to give legal testimony—unless they are a Prophet.[56] According to Ashari, the existence of jinn can not be proven, because arguments concerning the existence of jinn are beyond human comprehension. Adepts of Ashʿari theology explained jinn are invisible to humans, because they lack the appropriate sense organs to envision them.[57] Sceptics argued, doubting the existence of jinn, if jinn exist, their bodies must either be ethereal or made of solid material; if they were composed of the former, they would not able to do hard work, like carrying heavy stones. If they were composed of the latter, they would be visible to any human with functional eyes.[58] Therefore, sceptics refused to believe in a literal reading on jinn in Islamic sacred texts, preferring to view them as "unruly men" or metaphorical.[30] On the other hand, advocates of belief in jinn assert that God's creation can exceed the human mind; thus, jinn are beyond human understanding. Since they are mentioned in Islamic texts, scholars such as Ibn Taimiyya and Ibn Hazm prohibit the denial of jinn. They also refer to spirits and demons among the Christians, Zoroastrians and Jews to "prove" their existence.[58] Ibn Taymiyya believed the jinn to be generally "ignorant, untruthful, oppressive and treacherous". He held that the jinn account for much of the "magic" that is perceived by humans, cooperating with magicians to lift items in the air, delivering hidden truths to fortune tellers, and mimicking the voices of deceased humans during seances.[59]

Other critics, such as Jahiz and Mas'udi, related sightings of jinn to psychological causes. According to Mas'udi, the jinn as described by traditional scholars, are not a priori false, but improbable. Jahiz states in his work Kitab al-Hayawan that loneliness induces humans to mind-games and wishful thinking, causing waswās (whisperings in the mind, traditionally thought to be caused by Satan). If he is afraid, he may see things that are not real. These alleged appearances are told to other generations in bedtime stories and poems, and with children of the next generation growing up with such stories, when they are afraid or lonely, they remember these stories, encouraging their imaginations and causing another alleged sighting of jinn. However, Jahiz is less critical about jinn and demons than Mas'udi, stating human fantasy at least encourage people to imagine such creatures.[60] The Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya, attributed to the famous Sufi Shaikh Ibn Arabi, reconciles a literal existence of jinn with the imaginal, describing the appearance of jinn as a reflection of the observer and the place they are found. They differ from the angels, which due to their closeness to heaven reflect the spheres of the divine, mainly in their distance to the earth and the heavens, stating: "Only this much is different: The spirits of the jinn are lower spirits, while the spirits of angels are heavenly spirits".[61] The jinn share, due to their intermediary abode both angelic and human traits. Because jinn are closer to the material realm, it would be easier for human to contact a jinn, than an angel.[62]

In folk literature

Jinn can be found in the One Thousand and One Nights story of "The Fisherman and the Jinni";[63] more than three different types of jinn are described in the story of Ma‘ruf the Cobbler;[64][65] two jinn help young Aladdin in the story of Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp;[66] as Ḥasan Badr al-Dīn weeps over the grave of his father until sleep overcomes him, and he is awoken by a large group of sympathetic jinn in the Tale of ‘Alī Nūr al-Dīn and his son Badr ad-Dīn Ḥasan.[67] In some stories, jinn are credited with the ability of instantaneous travel (from China to Morocco in a single instant); in others, they need to fly from one place to another, though quite fast (from Baghdad to Cairo in a few hours).

Modern era

Modern Salafi tenets of Islam, refuse reinterpretations of jinn and adhere to literalism, arguing the threat of jinn and their ability to possess humans, could be proven by Quran and Sunnah.[68] However, many Salafis differ from their understanding of jinn from earlier accounts. Fatwas issued by Salafi scholars are often repetitive and limit the scope of all their answers to the same Quran verses and hadith quotes, without further investigating the traditions associated with and missing any reference to the individual experience. By that, a vast amount of traditions and beliefs among Muslims is excluded from contemporary theological discourse and downplaying embedded Muslim beliefs as local lore, such as symptoms of jinn possession. The opinions of the prominent Saudi Muslim lecturer Muhammad Al-Munajjid, an important scholar in Salafism and founder of IslamQA, are repeated over several online sources, and is also cited by IslamOnline and Islamicity.com for information about jinn, devils and angels. Similar Islamawareness.net and IslamOnline both feature the article about jinn written by Fethullah Gulen, using a similar approach to interpret the spiritual world.[69] Further, there is no distinction made between devils and demons and the jinn, indifferent spirits, as Salafi scholars Umar Sulaiman Al-Ashqar stated,[70] that demons are actually simply unbelieving jinn. Further Muhammad Al-Munajjid, asserts that reciting various Quranic verses and adhkaar (devotional acts involving the repetition of short sentences glorifying God) "prescribed in Sharia (Islamic law)" can protect against jinn,[56] associating Islamic healing rituals common across Islamic culture with shirk (polytheism).[71] For that reason, jinn are taken as serious danger by adherents of Salafism.[citation needed] Saudi Arabia, following the Wahhabism strant of Salafism, imposes a death penalty for dealing with jinn to prevent sorcery and witchcraft.[72][73] Contrary to the official teachings of modern Islam, cultural beliefs about jinn remained popular among Muslim societies and their understanding of cosmology and anthropology.[74]

Ahmadi interpret jinn not as supernatural beings, but as powerful men whose influence is felt even though they keep their distance from the common people. According to Mirza Tahir Ahmad, references to jinn could also mean microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses.[75] Others try to reconcile the traditional perspective on jinn, with modern sciences. Fethullah Gülen, leader of Hizmet movement, had put forward the idea, that jinn may be the cause of schizophrenia and cancer and that the Quranic references to jinn on "smokeless fire" could for that matter mean "energy".[76] Others again refuse connections between illness and jinn, but still believe in their existence, due to their occurrences in the Quran.[77] Many Modernists tend to reject the belief in jinn as superstition, holding back Islamic society. References to jinn in the Quran are interpreted in their ambiguous meaning of something invisible, and might be forces or simply angels.[78] Otherwise the importance of belief in jinn to Islamic belief in contemporary Muslim society was underscored by the judgment of apostasy by an Egyptian Sharia court in 1995 against liberal theologian Nasr Abu Zayd.[79] Abu Zayd was declared an unbeliever of Islam for — among other things — arguing that the reason for the presence of jinn in the Quran was that they (jinn) were part of Arab culture at the time of the Quran's revelation, rather than that they were part of God's creation.[32] Death threats led to Nasr Abu Zayd's leaving Egypt several weeks later.[Note 1]

Affirmation on the existence of jinn as sapient creatures living along with humans is still widespread in the Middle Eastern world and mental illnesses are still often attributed to jinn possession.[81]

Prevalence of belief

According a survey undertaken by the Pew Research Center in 2012, at least 86% in Morocco, 84% in Bangladesh, 63% in Turkey, 55% in Iraq, 53% in Indonesia, 47% in Thailand and 15% elsewhere in Central Asia, Muslims affirm the existence of jinn. The low rate in Central Asia might be influenced by Soviet religious oppression.[82]

Sleep paralysis is conceptualized as a "Jinn attack" by many sleep paralysis sufferers in Egypt as discovered by Cambridge neuroscientist Baland Jalal.[83] A scientific study found that as many as 48 percent of those who experience sleep paralysis in Egypt believe it to be an assault by the jinn.[83] Almost all of these sleep paralysis sufferers (95%) would recite verses from the Quran during sleep paralysis to prevent future "Jinn attacks". In addition, some (9%) would increase their daily Islamic prayer (salah) to get rid of these attacks by jinn.[83] Sleep paralysis is generally associated with great fear in Egypt, especially if believed to be supernatural in origin.[84]

Ǧinn (jinn) and shayāṭīn (demons/devils)

Both Islamic and non-Islamic scholarship generally distinguishes between angels, jinn and demons as three different types of spiritual entities in Islamic traditions.[85][86] The lines between demons and jinn are often blurred. Especially in folklore, jinn share many characteristics usually associated with demons, as both are held responsible for mental illness, diseases and possession. However, such traits do not appear within the Quran or canonical hadiths. The Quran emphasizes comparison between humans and jinn as taqalan (accountable ones, that means they have free-will and will be judged according to their deeds).[87][86] Since the demons are exclusively evil, they are not among taqalan, thus like angels, their destiny is prescribed.[88] Folkore differentiates both types of creatures as well. Field researches in 2001-2002, among Sunni Muslims in Syria, recorded many oral-tales about jinn. Tales about the Devil (Iblīs) and his lesser demons (shayāṭīn) barely appeared, in contrast to tales about jinn, who featured frequently in everyday stories. It seems the demons are primarily associated with their role within Islamic scriptures, as abstract forces tempting Muslims into everything disapproved by society, while jinn can be encountered by humans in lonley places.[89] This fits the general notion that the demons whisper into the heart of humans, but do not possess them physically.[90] Since the term shaitan is also used as an epithet to describe the taqalan (humans and jinn), naming malevolent jinn also shayāṭīn in some sources, it is sometimes difficult to hold them apart.[91][92] Strikingly, it seems Satan and his devilish hosts of demons (shayatin) generally appear in traditions associated with Judeo-Christian narratives, while jinn represent entities of polytheistic background.[c]

Depictions

Supernaturality

Jinn are not supernatural in the sense of being purely spiritual and transcendent to nature; while they are believed to be invisible (or often invisible) they also eat, drink, sleep, breed with the opposite sex, with offspring that resemble their parents. Intercourse is not limited to the jinn alone, but also possible between human and jinn. However, the practice is despised (makruh) in Islamic law. It is disputed whether or not, such intercourse can result in offsprings or not. They are "natural" in the classical philosopical sense by consisting of an element, undergoing change and being bound in time and space.[94] They resemble spirits or demons in the sense of evading sensible perception, but are not of immaterial nature as Rūḥāniyya are.[95] Thus they interact in a tactile manner with people and objects. In scientific treatises the jinn are included and depicted as animals (hayawan) with a subtle body.[96] The Qanoon-e-Islam, written 1832 by Sharif Ja'far, writing about jinn-belief in India, states that their body constitutes 90% of spirit and 10% of flesh.[97] They resemble humans in many regards, their subtle matter being the only main difference. But it is this very nature, that enables them to change their shape, move quickly, fly and entering human bodies, causing epilepsy and illness, hence the temptation for humans to make them allies by means of magical practices.[98]

Unlike the jinn in Islamic belief and folklore, jinn in Middle Eastern folktales, depicted as magical creatures, are unlike the former, generally considered to be fictional.[99]

Appearance

The appearance of jinn can be divided into three major categories:[100]

Zoomorphic manifestation

Jinn are assumed to be able to appear in shape of various animals such as scorpions, cats, owls and onagers. The dog is also often related to jinn, especially black dogs. However piebald dogs are rather identified with hinn. Associations between dogs and jinn prevailed in Arabic-literature, but lost its meaning in Persian scriptures.[101] Serpents are the animals most associated with jinn. Islamic traditions knows many narratitions concerning a serpent who was actually a jinni.[102] However (except for the 'udhrut from Yemeni folklore) the jinn can not appear in form of wolves. The wolf is thought of as the natural predator of the jinn, who contrasts the jinn by his noble character and disables them to vanish.[103][42]

Jinn in form of storms and shadows

The jinn are also related to the wind. They may appear in mists or sandstorms.[104] Zubayr ibn al-Awam, who is held to have accompanied Muhammad during his lecture to the jinn, is said to view the jinn as shadowy ghosts with no individual structure.[27] According to a narration Ghazali asked Ṭabasī, famous for jinn-incantations, to reveal the jinn to him. Accordingly, Tabasi showed him the jinn, seeing them like they were "a shadow on the wall". After Ghazali requested to speak to them, Ṭabasī stated, that for now he could not see more.[105] Although sandstorms are believed to be caused by jinn, others, such as Abu Yahya Zakariya' ibn Muhammad al-Qazwini and Ghazali attribute them to natural causes.[106] Otherwise sandstorms are thought to be caused by a battle between different groups of jinn.

Anthropomorphic manifestation

A common characteristic of the jinn is their lack of individuality, but they may gain individuality by materializing in human forms,[107] such as Sakhr and several jinn known from magical writings. But also in their anthropomorphic shape, they stay partly animal and are not fully human. Therefore, individual jinn are commonly depicted as monstrous and anthropomorphized creatures with body parts from different animals or human with animal traits.[108] Commonly associated with jinn in human form are the Si'lah and the Ghoul. However, since they stay partly animal, their bodies are depicted as fashioned out of two or more different species.[109] Some of them may have the hands of cats, the head of birds or wings rise from their shoulders.[110]

In witchcraft and magical literature

Witchcraft (Arabic: سِحْر sihr, which is also used to mean "magic, wizardry") is often associated with jinn and afarit[111] around the Middle East. Therefore, a sorcerer may summon a jinn and force him to perform orders. Summoned jinn may be sent to the chosen victim to cause demonic possession. Such summonings were done by invocation,[112] by aid of talismans or by satisfying the jinn, thus to make a contract.[113] Jinn are also regarded as assistants of soothsayers. Soothsayers reveal information from the past and present; the jinn can be a source of this information because their lifespans exceed those of humans.[34] Another way to subjugate them, is by inserting a needle to their skin or dress. Since jinn are afraid of iron, they are unable to remove it with their own power.[114]

Ibn al-Nadim, Muslim scholar of his Kitāb al-Fihrist, describes a book that lists 70 Jinn led by Fuqtus (Arabic: Fuqṭus فقْطس), including several jinn appointed over each day of the week.[115][116] Bayard Dodge, who translated al-Fihrist into English, notes that most of these names appear in the Testament of Solomon.[115] A collection of late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century magico-medical manuscripts from Ocaña, Spain describes a different set of 72 jinn (termed "Tayaliq") again under Fuqtus (here named "Fayqayțūš" or Fiqitush), blaming them for various ailments.[117][118] According to these manuscripts, each jinni was brought before King Solomon and ordered to divulge their "corruption" and "residence" while the Jinn King Fiqitush gave Solomon a recipe for curing the ailments associated with each jinni as they confessed their transgressions.[119]

A disseminated treatise on the occult, written by al-Ṭabasī, called Shāmil, deals with subjugating demons and jinn by incantations, charms and the combination of written and recited formulae and to obtain supernatural powers through their aid. Al-Ṭabasī distinguished between licit and illicit magic, the later founded on disbelief, while the first on purity.[120]

Seven kings of the Jinn are traditionally associated with days of the week.[121] They are also attesteed in the Book of Wonders. Although many passages are damaged, they remain in Ottoman copies. These jinn-kings (sometimes afarit instead) are invoked to legitimate spells performed by amulets.[122]

- Sunday: Al-Mudhib (Abu 'Abdallah Sa'id)

- Monday: Murrah al-Abyad Abu al-Harith (Abu al-Nur)

- Tuesday: Abu Mihriz (or Abu Ya'qub) Al-Ahmar

- Wednesday: Barqan Abu al-'Adja'yb

- Thursday: Shamhurish (al-Tayyar)

- Friday: Abu Hasan Zoba'ah (al-Abyad)

- Saturday: Abu Nuh Maimun

During the Rwandan genocide, both Hutus and Tutsis avoided searching local Rwandan Muslim neighborhoods because they widely believed the myth that local Muslims and mosques were protected by the power of Islamic magic and the efficacious jinn.[citation needed] In the Rwandan city of Cyangugu, arsonists ran away instead of destroying the mosque because they feared the wrath of the jinn, whom they believed were guarding the mosque.[123]

Comparative mythology

Ancient Mesopotamian religion

Beliefs in entities similar to the jinn are found throughout pre-Islamic Middle Eastern cultures.[19] The ancient Sumerians believed in Pazuzu, a wind demon,[19][124]: 147–148 who was shown with "a rather canine face with abnormally bulging eyes, a scaly body, a snake-headed penis, the talons of a bird and usually wings."[124]: 147 The ancient Babylonians believed in utukku, a class of demons which were believed to haunt remote wildernesses, graveyards, mountains, and the sea, all locations where jinn were later thought to reside.[19] The Babylonians also believed in the Rabisu, a vampiric demon believed to leap out and attack travelers at unfrequented locations, similar to the post-Islamic ghūl,[19] a specific kind of jinn whose name is etymologically related to that of the Sumerian galla, a class of Underworld demon.[125][126]

Lamashtu, also known as Labartu, was a divine demoness said to devour human infants.[19][124]: 115 Lamassu, also known as Shedu, were guardian spirits, sometimes with evil propensities.[19][124]: 115–116 The Assyrians believed in the Alû, sometimes described as a wind demon residing in desolate ruins who would sneak into people's houses at night and steal their sleep.[19] In the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra, entities similar to jinn were known as ginnayê,[19] an Aramaic name which may be etymologically derived from the name of the genii from Roman mythology.[19] Like jinn among modern-day Bedouin, ginnayê were thought to resemble humans.[19] They protected caravans, cattle, and villages in the desert[19] and tutelary shrines were kept in their honor.[19] They were frequently invoked in pairs.[19]

Judaism

The description of jinn are almost identical with the shedim from Jewish mythology. As with the jinn, whom soe of them follow the law brought by Muhammad, some of the shedim are believed to be followers of the law of Moses and consequently good.[127] Both are said to be invisible to human eyes but are nevertheless subject to bodily desires, like procreating and the need to eat. Some Jewish sources agree with the Islamic notion, that jinn inhabited the world before humans.[128][129] Asmodeus appears both as an individual of the jinn or shedim, as an antagonist of Solomon.[99]: 120

Buddhism

Similar to the Islamic idea of spiritual entities converting to one's own religion can be found on Buddhism lore. Accordingly, Buddha preached among humans, Devas, Asura spiritual entities who are like humans subject to the cycle of life, that resembles the Islamic notion of jinn, who are also ontologically placed among humans in regard of eschatological destiny.[130][131]

Christianity

Van Dyck's Arabic translation of the Old Testament uses the alternative collective plural "jann" (Arab:الجان); translation:al-jānn) to render the Hebrew word usually translated into English as "familiar spirit" (אוב , Strong #0178) in several places (Leviticus 19:31, 20:6, 1 Samuel 28:3,7,9, 1 Chronicles 10:13).[132]

Some scholars evaluated whether or not the jinn might be compared to fallen angels in Christian traditions. Comparable to Augustine's descriptions of fallen angels as ethereal, the jinn seems to be considered as the same substance. Although the myth of fallen angels is not absent in the Quran,[133] the jinn nevertheless differ in their major characteristics from that of fallen angels: While fallen angels fell from heaven, the jinn did not, but try to climb up to it in order to receive the news of the angels.[134]

In popular culture

See also

- Black dog (ghost)

- Chort

- Çor

- Daeva

- Daemon (classical mythology)

- Demonology

- Exorcism in Islam

- Fairy

- Genie in popular culture

- Genius loci

- Genius (mythology)

- Ghosts

- Ghoul (Jinn who dwell within graveyards)

- Hinn

- Houri

- Iblis

- Ifrit

- Marid

- Nasnas

- Peri

- Qareen

- Qutrub

- Rig-e Jenn

- Shadow People

- Shayṭān (Troops of devils headed by Iblis)

- Shedim

- Sila

- Supernatural

- Theriocephaly

- Will of the wisp

- Winged genie

- Yazata

- Yōkai

References

Notes

- ^ "M. Dols points out that jinn-belief is not a strictly Islamic concept. It rather includes countless elements of idol-worship, as Muhammad's enemies practised in Mecca during jahilliya. According to F. Meier early Islam integrated many pagan deities into its system by degrading them to spirits. 1. In Islam, the existence of spirits that are neither angels nor necessarily devils is acknowledged. 2. Thereby Islam is able to incorporate non-biblical[,] non-Quranic ideas about mythic images, that means: a. degrading deities to spirits and therefore taking into the spiritual world. b. taking daemons, not mentioned in the sacred traditions of Islam, of uncertain origin. c. consideration of spirits to tolerate or advising to regulate them." Original: "M. Dols macht darauf aufmerksam, dass der Ginn-Glaube kein strikt islamisches Konzept ist. Er beinhaltet vielmehr zahllose Elemente einer Götzenverehrung, wie sie Muhammads Gegner zur Zeit der gahiliyya in Mekka praktizierten. Gemäß F. Meier integrierte der junge Islam bei seiner raschen Expansion viele heidnische Gottheiten in sein System, indem er sie zu Dämonen degradierte. 1. Im Islam wird die Existenz von Geistern, die weder Engel noch unbedingt Teufel sein müssen, anerkannt. 2. Damit besitzt der Islam die Möglichkeit, nicht-biblische[,] nicht koranische Vorstellungen von mythischen Vorstellungen sich einzuverleiben, d.h.: a. Götter zu Geistern zu erniedrigen und so ins islamische Geisterreich aufzunehmen. b. in der heiligen Überlieferung des Islams nicht eigens genannte Dämonen beliebiger Herkunft zu übernehmen. c. eine Berücksichtigung der Geister zu dulden oder gar zu empfehlen und sie zu regeln."[4]

- ^ sometimes arab use Jānn (Template:Lang-ar) term for singular, jānn also referred to jinn world, another plural, snakes/serpents and another type of jinn

- ^ "Simplyfied, it can be stated that devils and Iblis apprear in reports with Jewish background. Depictions, whose actors are referred to as jinn are generally located apart from Judeo-Christian traditions." "Vereinfacht lässt sich festhalten, dass Satane und Iblis in Berichten mit jüdischem Hintergrund auftreten. Darstellungen, deren Akteure als ginn bezeichnet werden, sind in der Regel außerhalb der jüdischen-christlichen Überlieferung zu verorten."[93]

Citations

- ^ "jinn – Definition of jinn in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries – English.

- ^ a b Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 22 (German)

- ^ Abu l-Lait as-Samarqandi's Comentary on Abu Hanifa al-Fiqh al-absat Introduction, Text and Commentary by Hans Daiber Islamic concept of Belief in the 4th/10th Century Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa p. 243

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 2 (German)

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill: VOlume 3, 2005 ISBN 9789004123564 p. 45

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 67 (German)

- ^ Edward William Lane. "An Arabic-English Lexicon". Archived from the original on 8 April 2015.. p. 462.

- ^ Wehr, Hans (1994). Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (4 ed.). Urbana, Illinois: Spoken Language Services. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-87950-003-0.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 38

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 25 (German)

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 24 (German)

- ^ Tisdall, W. St. Clair. The Original Sources of the Qur'an, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, 1905

- ^ The Religion of the Crescent or Islam: Its Strength, Its Weakness, Its Origin, Its Influence, William St. Clair Tisdall, 1895

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. "genie, n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2014.

- ^ Arabian Nights' entertainments, vol. Vol. I, 1706, p. 14

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help). - ^ John L. Mckenzie The Dictionary Of The Bible Simon and Schuster 1995 ISBN 9780684819136 p. 192

- ^ Mehmet-Ali Ataç The Mythology of Kingship in Neo-Assyrian Art Cambridge University Press 2010 ISBN 9780521517904 p. 36

- ^ Christopher R. Fee, Jeffrey B. Webb American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore (3 Volumes) ABC-CLIO, 29 Aug 2016 isbn 978-1-610-69568-8 p. 527

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Lebling, Robert (2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. New York City, New York and London, England: I. B. Tauris. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 34

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 122

- ^ a b Irving M. Zeitlin (19 March 2007). The Historical Muhammad. Polity. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-7456-3999-4.

- ^ https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/cin

- ^ Robert Lebling (30 July 2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. p. 21 ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3

- ^ Quran 51:56–56

- ^ Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb al-Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, I, p. 68; Abū al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān, pp. 193, 341

- ^ a b Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 64

- ^ Paul Arno Eichler: Die Dschinn, Teufel und Engel in Koran. 1928 P. 16-32 (German)

- ^ Christopher R. Fee, Jeffrey B. Webb American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore (3 Volumes) ABC-CLIO 2016 ISBN 978-1-610-69568-8 page 527

- ^ a b c d e f Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1885). "Genii". Dictionary of Islam: Being a Cyclopædia of the Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies . London, UK: W.H.Allen. pp. 134–6. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Ashqar, ʻUmar Sulaymān (1998). The World of the Jinn and Devils. Islamic Books. p. 8. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 46–7. ISBN 0192853449.

The Koran : A Very Short Introduction.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 18

- ^ a b John Andrew Morrow Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism McFarland, 27 November 2013 ISBN 978-1-476-61288-1 page 73

- ^ Stephen J. Vicchio Biblical Figures in the Islamic Faith Wipf and Stock Publishers 2008 ISBN 978-1-556-35304-8 page 183

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said, “Angels”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 06 October 2019 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23204> First published online: 2009 First print edition: 9789004181304, 2009, 2009-3

- ^ Scott B. Noegel, Brannon M. Wheeler The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism Scarecrow Press 2010 ISBN 978-1-461-71895-6 page 170

- ^ University of Michigan Muhammad Asad: Europe's Gift to Islam, Band 1 Truth Society 2006 ISBN 978-9-693-51852-8 page 387

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-710-31356-0 page 302

- ^ Husam Muhi Eldin al- Alousi The Problem of Creation in Islamic Thought, Qur'an, Hadith, Commentaries, and KalamNational Printing and Publishing, Bagdad, 1968 p. 26

- ^ Fahd, T. and Rippin, A., “S̲h̲ayṭān”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 06 October 2019 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1054> First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007

- ^ a b Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 43 (German)

- ^ Gabriel Said Reynolds The Qur'an and Its Biblical Subtext Routledge 2010 ISBN 978-1-135-15020-4 page 41

- ^ Tubanur Yesilhark Ozkan A Muslim Response to Evil: Said Nursi on the Theodicy Routledge 2016 ISBN 978-1-317-18754-7 page 141

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 43 (German)

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 52

- ^ Juan Eduardo Campo Encyclopedia of Islam Infobase Publishing 2009 ISBN 978-1-438-12696-8 page 402

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 519 (German)

- ^ Girls' Dormitory: Women's Islam and Iranian Horror PEDRAM PARTOVI First published: 03 December 2009

- ^ Joseph P. Laycock Spirit Possession around the World: Possession, Communion, and Demon Expulsion across Cultures: Possession, Communion, and Demon Expulsion across Cultures ABC-CLIO 2015 ISBN 978-1-610-69590-9 page 243

- ^ MacDonald, D.B., Massé, H., Boratav, P.N., Nizami, K.A. and Voorhoeve, P., “Ḏj̲inn”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 15 November 2019 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0191> First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4, 1960–2007

- ^ Lebling, Robert (2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. New York City, New York and London, England: I. B. Tauris. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Abu’l-Fotūḥ, XVII, pp. 280–281

- ^ Robert Elsie A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture C. Hurst & Co. Publishers 2001 ISBN 9781850655701 p. 134

- ^ MacDonald, D.B., Massé, H., Boratav, P.N., Nizami, K.A. and Voorhoeve, P., “Ḏj̲inn”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 15 November 2019 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0191> First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4, 1960–2007 (englisch)

- ^ a b Salih Al-Munajjid, Muhammed. "Protection From the Jinn". Islam Question and Answer. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 22

- ^ a b Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p.33 (German)

- ^ Ibn Taymiyyah, al-Furqān bayna awliyā’ al-Raḥmān wa-awliyā’ al-Shayṭān ("Essay on the Jinn"), translated by Abu Ameenah Bilal Phillips

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p.37 (German)

- ^ "http://www.ibnarabisociety.org/articles/futuhat_ch009.html

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 50

- ^ The fisherman and the Jinni at About.com Classic Literature

- ^ Idries Shah – Tales of the Dervishes at ISF website

- ^ "MA'ARUF THE COBBLER AND HIS WIFE".

- ^ The Arabian Nights – ALADDIN; OR, THE WONDERFUL LAMP at About.com Classic Literature

- ^ The Arabian Nights – TALE OF NUR AL-DIN ALI AND HIS SON BADR AL-DIN HASAN at About.com Classic Literature

- ^ "Jinn Entering Human Bodies - Islam Question & Answer".

- ^ Rothenberg, Celia E. "Islam on the Internet: the Jinn and the objectification of Islam." Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, vol. 23, no. 3, 2011, p. 358. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A292993199/AONE?u=hamburg&sid=AONE&xid=d23f2c2a. Accessed 6 Feb. 2020

- ^ "The Jinn - Islam Question & Answer".

- ^ TY - JOUR AU - Østebø, Terje PY - 2014 DA - 2014/01/01 TI - The revenge of the Jinns: spirits, Salafi reform, and the continuity in change in contemporary Ethiopia JO - Contemporary Islam SP - 17 EP - 36 VL - 8 IS - 1 AB - The point of departure for this article is a story about jinns taking revenge upon people who have abandoned earlier religious practices. It is a powerful account of their attempt to free themselves from a past viewed as inhabited by evil forces and about the encounter between contemporary Salafi reformism and a presumed disappearing religious universe. It serves to prove how a novel version of Islam has superseded former practices; delegitimized and categorized as belonging to the past. The story is, however, also an important source and an interesting entry-point to examine the continued relevance of past practices within processes of reform. Analyzing the story about the jinns and the trajectory of Salafi reform in Bale, this contribution demonstrates how the past remains intersected with present reformism, and how both former practices and novel impetuses are reconfigured through this process. The article pays attention to the dialectics of negotiations inherent to processes of reform and points to the manner in which the involvement of a range of different actors produces idiosyncratic results. It challenges notions of contemporary Islamic reform as something linear and fixed and argues that such processes are multifaceted and open-ended. SN - 1872-0226 UR - https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-013-0282-7 DO - 10.1007/s11562-013-0282-7 ID - Østebø2014 ER -

- ^ "The death penalty in Saudi Arabia: Facts and Figures".

- ^ "Saudi Arabia's War on Witchcraft". 19 August 2013.

- ^ PEDRAM PARTOVI Girls’ Dormitor y : Women’s Islam and Iranian Horror

- ^ Simon Ross Valentine (2008). Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at: History, Belief, Practice. Columbia University Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-231-70094-8.

- ^ John Grant Denying Science: Conspiracy Theories, Media Distortions, and the War Against Reality Prometheus Books ISBN 978-1-616-14400-5

- ^ Alireza Doostdar The Iranian Metaphysicals: Explorations in Science, Islam, and the Uncanny ISBN 978-1-400-88978-5 Princeton University Press 2018 page 54

- ^ Fr. Edmund Teuma THE NATURE OF "IBLI$H IN THE QUR'AN AS INTERPRETED BY THE COMMENTATORS 1980 University of Malta. Faculty of Theology

- ^ "Nasr Abu Zayd, Who Stirred Debate on Koran, Dies at 66". REUTERS. 6 July 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Abou El-Magd, Nadia. "When the professor can't teach". arabworldbooks.com. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

source Al-Ahram Weekly- 15–21 June 2000

- ^ G. Hussein Rassool Islamic Counselling: An Introduction to theory and practice Routledge, 16.07.2015 ISBN 978-1-31744-125-0 p. 58

- ^ G. Hussein Rassool Evil Eye, Jinn Possession, and Mental Health Issues: An Islamic Perspective Routledge, 16.08.2018 ISBN 9781317226987

- ^ a b c Jalal, Baland; Simons-Rudolph, Joseph; Jalal, Bamo; Hinton, Devon E. (1 October 2013). "Explanations of sleep paralysis among Egyptian college students and the general population in Egypt and Denmark". Transcultural Psychiatry. 51 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1177/1363461513503378. PMID 24084761.

- ^ Jalal, Baland; Hinton, Devon E. (1 September 2013). "Rates and Characteristics of Sleep Paralysis in the General Population of Denmark and Egypt". Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 37 (3): 534–548. doi:10.1007/s11013-013-9327-x. ISSN 0165-005X. PMID 23884906.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 21

- ^ a b Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 47 (German)

- ^ Eichler, Paul Arno, 1889 Die Dschinn, Teufel und Engel in Koran [microform] p. 60 (German)

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 100

- ^ Gebhard, Fartacek (2002). "Begegnungen mit Ǧinn. Lokale Konzeptionen über Geister und Dämonen in der syrischenPeripherie". Anthropos. 97 (2): 469–486. JSTOR 40466046.

- ^ Szombathy, Zoltan, “Exorcism”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 15 November 2019<http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_26268> First published online: 2014 First print edition: 9789004269637, 2014, 2014-4

- ^ Robert Lebling (30 July 2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 3 (German)

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 pp. 48, 286 (German)

- ^ Benjamin W. McCraw, Robert Arp Philosophical Approaches to the Devil Routledge 2015 ISBN 9781317392217

- ^ Chodkiewicz, M., “Rūḥāniyya”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 09 January 2020 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6323 First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007

- ^ Salim Ayduz The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam Oxford University Press, 2014 ISBN 9780199812578 p. 99

- ^ Lale Behzadi, Patrick Franke, Geoffrey Haig, Christoph Herzog, Birgitt Hoffmann, Lorenz Korn, Susanne Talabardon Bamberger Orientstudien University of Bamberg Press, 26 Feb 2015 ISBN 978-3-863-09286-3 p.127

- ^ Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Jeffrey Kripal Hidden Intercourse: Eros and Sexuality in the History of Western Esotericism BRILL, 16 Oct 2008 ISBN 9789047443582 pp. 50-55

- ^ a b Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 113 (German)

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 134 (German)

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 116 (German)

- ^ name="ReferenceA98">Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3 page 98

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Patrick. Dictionary of Islam. 1885. "Genii" p.136

- ^ Travis Zadeh Commanding Demons and Jinn: The Sorcerer in Early Islamic Thought p.145

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 147 (German)

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 153 (German)

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 164 (German)

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 164

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 160 (German)

- ^ Ian Richard Netton Encyclopaedia of Islam Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-135-17960-1 page 377

- ^ name="Robert Lebling">Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3 page 153

- ^ Gerda Sengers Women and Demons: Cultic Healing in Islamic Egypt BRILL 2003 ISBN 978-9-004-12771-5 page 31

- ^ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/genie-

- ^ a b Bayard Dodge, ed. and trans. The Fihrist of al-Nadim: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970. pp. 727–8.

- ^ Robert Lebling. Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B. Taurus, 2010. p.38

- ^ Celia del Moral. Magia y Superstitión en los Manuscritos de Ocaña (Toledo). Siglos XIV-XV. Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the Union Européenne des Arabisants et Islamisants, Part Two; A. Fodor, ed. Budapest, 10–17 September 2000. pp.109–121

- ^ Joaquina Albarracin Navarro & Juan Martinez Ruiz. Medicina, Farmacopea y Magia en el "Misceláneo de Salomón". Universidad de Granada, 1987. p.38 et passim

- ^ Shadrach, Nineveh (2007). The Book of Deadly Names. Ishtar Publishing. ISBN 978-0978388300.

- ^ Travis Zadeh Commanding Demons and Jinn: The Sorcerer in Early Islamic Thought Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2014 p-143-145

- ^ Robert Lebling (30 July 2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3.

- ^ Mommersteeg, Geert. “‘He Has Smitten Her to the Heart with Love’ The Fabrication of an Islamic Love-Amulet in West Africa.” Anthropos, vol. 83, no. 4/6, 1988, pp. 501–510. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40463380. Accessed 27 Mar. 2020

- ^ Kubai, Anne (April 2007). "Walking a Tightrope: Christians and Muslims in Post-Genocide Rwanda". Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. 18 (2): 219–235. doi:10.1080/09596410701214076.

- ^ a b c d Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Cramer, Marc (1979). The Devil Within. W.H. Allen. ISBN 978-0-491-02366-5.

- ^ "Cultural Analysis, Volume 8, 2009: The Mythical Ghoul in Arabic Culture / Ahmed Al-Rawi". Socrates.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ J. W. Moore, Savary (M., Claude Etienne)|The Koran: Commonly Called the Alcoran of Mohammed|1853|J. W. Moore| p. 20

- ^ Carol K. Mack, Dinah Mack A Field Guide to Demons, Vampires, Fallen Angels and Other Subversive Spirits Skyhorse Publishing 2013 ISBN 978-1-628-72150-8

- ^ "Shedim: Eldritch Beings from Jewish Folklore". 7 March 2014.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 165

- ^ Marie Musæus-Higgins Poya Days Asian Educational Services 1925 ISBN 978-8-120-61321-8 page 14

- ^ "Arabic Bible – Arabic Bible Outreach Ministry". arabicbible.com.

- ^ Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Jeffrey Kripal Hidden Intercourse: Eros and Sexuality in the History of Western Esotericism BRILL, 16.10.2008 ISBN 9789047443582 p. 53

- ^ Mehdi Azaiez, Gabriel Said Reynolds, Tommaso Tesei, Hamza M. Zafer The Qur'an Seminar Commentary / Le Qur'an Seminar: A Collaborative Study of 50 Qur'anic Passages / Commentaire collaboratif de 50 passages coraniques Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG ISBN 9783110445459 Q 72

Bibliography

- Al-Ashqar, Dr. Umar Sulaiman (1998). The World of the Jinn and Devils. Boulder, CO: Al-Basheer Company for Publications and Translations.

- Barnhart, Robert K. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. 1995.

- "Genie". The Oxford English Dictionary. Second edition, 1989.

- Abu al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān IX-XVII (pub. so far), Tehran, 1988.

- Moḥammad Ayyūb Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, ed. J. Matīnī, Tehran, 1971.

- A. Aarne and S. Thompson, The Types of the Folktale, 2nd rev. ed., Folklore Fellows Communications 184, Helsinki, 1973.

- Abu’l-Moayyad Balkhī, Ajā’eb al-donyā, ed. L. P. Smynova, Moscow, 1993.

- A. Christensen, Essai sur la Demonologie iranienne, Det. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser, 1941.

- R. Dozy, Supplément aux Dictionnaires arabes, 3rd ed., Leyden, 1967.

- H. El-Shamy, Folk Traditions of the Arab World: A Guide to Motif Classification, 2 vols., Bloomington, 1995.

- Abū Bakr Moṭahhar Jamālī Yazdī, Farrokh-nāma, ed. Ī. Afshār, Tehran, 1967.

- Abū Jaʿfar Moḥammad Kolaynī, Ketāb al-kāfī, ed. A. Ghaffārī, 8 vols., Tehran, 1988.

- Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, Beirut, 1968.

- L. Loeffler, Islam in Practice: Religious Beliefs in a Persian Village, New York, 1988.

- U. Marzolph, Typologie des persischen Volksmärchens, Beirut, 1984. Massé, Croyances.

- M. Mīhandūst, Padīdahā-ye wahmī-e dīrsāl dar janūb-e Khorāsān, Honar o mordom, 1976, pp. 44–51.

- T. Nöldeke "Arabs (Ancient)", in J. Hastings, ed., Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics I, Edinburgh, 1913, pp. 659–73.

- S. Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, rev. ed., 6 vols., Bloomington, 1955.

- S. Thompson and W. Roberts, Types of Indic Oral Tales, Folklore Fellows Communications 180, Helsinki, 1960.

- Solṭān-Moḥammad ibn Tāj al-Dīn Ḥasan Esterābādī, Toḥfat al-majāles, Tehran.

- Nünlist, Tobias (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4.

- Moḥammad b. Maḥmūd Ṭūsī, Ajāyeb al-makhlūqāt va gharā’eb al-mawjūdāt, ed. M. Sotūda, Tehran, 1966.

Further reading

- Crapanzano, V. (1973) The Hamadsha: a study in Moroccan ethnopsychiatry. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

- Drijvers, H. J. W. (1976) The Religion of Palmyra. Leiden, Brill.

- El-Zein, Amira (2009) Islam, Arabs, and the intelligent world of the Jinn. Contemporary Issues in the Middle East. Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3200-9.

- El-Zein, Amira (2006) "Jinn". In: J. F. Meri ed. Medieval Islamic civilization – an encyclopedia. New York and Abingdon, Routledge, pp. 420–421.

- Goodman, L.E. (1978) The case of the animals versus man before the king of the Jinn: A tenth-century ecological fable of the pure brethren of Basra. Library of Classical Arabic Literature, vol. 3. Boston, Twayne.

- Maarouf, M. (2007) Jinn eviction as a discourse of power: a multidisciplinary approach to Moroccan magical beliefs and practices. Leiden, Brill.

- Taneja, Anand V. (2017) Jinnealogy: Time, Islam, and Ecological Thought in the Medieval Ruins of Delhi. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1503603936

- Zbinden, E. (1953) Die Djinn des Islam und der altorientalische Geisterglaube. Bern, Haupt.