Cretaceous

Template:Geological period The Cretaceous ( /krɪˈteɪ.ʃəs/, krih-TAY-shəs)[1] is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (mya). It is platelet surgery mastic uvula the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. The name is derived from the Latin creta, "chalk". It is usually abbreviated K, for its German translation Kreide.

The Cretaceous was a period with a relatively warm climate, resulting in high eustatic sea levels that created numerous shallow inland seas. These oceans and seas were populated with now-extinct marine reptiles, ammonites and rudists, while dinosaurs continued to dominate on land. During this time, new groups of mammals and birds, as well as flowering plants, appeared.

The Cretaceous (along with the Mesozoic) ended with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, a large mass extinction in which many groups, including non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs and large marine reptiles died out. The end of the Cretaceous is defined by the abrupt Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–Pg boundary), a geologic signature associated with the mass extinction which lies between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras.

Geology

Research history

The Cretaceous as a separate period was first defined by Belgian geologist Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1822,[2] using strata in the Paris Basin[3] and named for the extensive beds of chalk (calcium carbonate deposited by the shells of marine invertebrates, principally coccoliths), found in the upper Cretaceous of Western Europe.[a] The name Cretaceous was derived from Latin creta, meaning chalk.[4]

Stratigraphic subdivisions

The Cretaceous is divided into Early and Late Cretaceous epochs, or Lower and Upper Cretaceous series. In older literature the Cretaceous is sometimes divided into three series: Neocomian (lower/early), Gallic (middle) and Senonian (upper/late). A subdivision in eleven stages, all originating from European stratigraphy, is now used worldwide. In many parts of the world, alternative local subdivisions are still in use.

As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds of the Cretaceous are well identified but the exact age of the system's base is uncertain by a few million years. No great extinction or burst of diversity separates the Cretaceous from the Jurassic. However, the top of the system is sharply defined, being placed at an iridium-rich layer found worldwide that is believed to be associated with the Chicxulub impact crater, with its boundaries circumscribing parts of the Yucatán Peninsula and into the Gulf of Mexico. This layer has been dated at 66.043 Ma.[5]

A 140 Ma age for the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary instead of the usually accepted 145 Ma was proposed in 2014 based on a stratigraphic study of Vaca Muerta Formation in Neuquén Basin, Argentina.[6] Víctor Ramos, one of the authors of the study proposing the 140 Ma boundary age, sees the study as a "first step" toward formally changing the age in the International Union of Geological Sciences.[7]

From youngest to oldest, the subdivisions of the Cretaceous period are:

Maastrichtian – (66-72.1 Mya)

Campanian – (72.1-83.6 Mya)

Santonian – (83.6-86.3 Mya)

Coniacian – (86.3-89.8 Mya)

Turonian – (89.8-93.9 Mya)

Cenomanian – (93.9-100.5 Mya)

Albian – (100.5-113.0 Mya)

Aptian – (113.0-125.0 Mya)

Barremian – (125.0-129.4 Mya)

Hauterivian – (129.4-132.9 Mya)

Valanginian – (132.9-139.8 Mya)

Berriasian – (139.8-145.0 Mya)

Rock formations

The high sea level and warm climate of the Cretaceous meant large areas of the continents were covered by warm, shallow seas, providing habitat for many marine organisms. The Cretaceous was named for the extensive chalk deposits of this age in Europe, but in many parts of the world, the deposits from the Cretaceous are of marine limestone, a rock type that is formed under warm, shallow marine circumstances. Due to the high sea level, there was extensive space for such sedimentation. Because of the relatively young age and great thickness of the system, Cretaceous rocks are evident in many areas worldwide.

Chalk is a rock type characteristic for (but not restricted to) the Cretaceous. It consists of coccoliths, microscopically small calcite skeletons of coccolithophores, a type of algae that prospered in the Cretaceous seas.

In northwestern Europe, chalk deposits from the Upper Cretaceous are characteristic for the Chalk Group, which forms the white cliffs of Dover on the south coast of England and similar cliffs on the French Normandian coast. The group is found in England, northern France, the low countries, northern Germany, Denmark and in the subsurface of the southern part of the North Sea. Chalk is not easily consolidated and the Chalk Group still consists of loose sediments in many places. The group also has other limestones and arenites. Among the fossils it contains are sea urchins, belemnites, ammonites and sea reptiles such as Mosasaurus.

In southern Europe, the Cretaceous is usually a marine system consisting of competent limestone beds or incompetent marls. Because the Alpine mountain chains did not yet exist in the Cretaceous, these deposits formed on the southern edge of the European continental shelf, at the margin of the Tethys Ocean.

Stagnation of deep sea currents in middle Cretaceous times caused anoxic conditions in the sea water leaving the deposited organic matter undecomposed. Half of the world's petroleum reserves were laid down at this time in the anoxic conditions of what would become the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mexico. In many places around the world, dark anoxic shales were formed during this interval.[8] These shales are an important source rock for oil and gas, for example in the subsurface of the North Sea.

Paleogeography

During the Cretaceous, the late-Paleozoic-to-early-Mesozoic supercontinent of Pangaea completed its tectonic breakup into the present-day continents, although their positions were substantially different at the time. As the Atlantic Ocean widened, the convergent-margin mountain building (orogenies) that had begun during the Jurassic continued in the North American Cordillera, as the Nevadan orogeny was followed by the Sevier and Laramide orogenies.

Though Gondwana was still intact in the beginning of the Cretaceous, it broke up as South America, Antarctica and Australia rifted away from Africa (though India and Madagascar remained attached to each other); thus, the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans were newly formed. Such active rifting lifted great undersea mountain chains along the welts, raising eustatic sea levels worldwide. To the north of Africa the Tethys Sea continued to narrow. Broad shallow seas advanced across central North America (the Western Interior Seaway) and Europe, then receded late in the period, leaving thick marine deposits sandwiched between coal beds. At the peak of the Cretaceous transgression, one-third of Earth's present land area was submerged.[9]

The Cretaceous is justly famous for its chalk; indeed, more chalk formed in the Cretaceous than in any other period in the Phanerozoic.[10] Mid-ocean ridge activity—or rather, the circulation of seawater through the enlarged ridges—enriched the oceans in calcium; this made the oceans more saturated, as well as increased the bioavailability of the element for calcareous nanoplankton.[11] These widespread carbonates and other sedimentary deposits make the Cretaceous rock record especially fine. Famous formations from North America include the rich marine fossils of Kansas's Smoky Hill Chalk Member and the terrestrial fauna of the late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation. Other important Cretaceous exposures occur in Europe (e.g., the Weald) and China (the Yixian Formation). In the area that is now India, massive lava beds called the Deccan Traps were erupted in the very late Cretaceous and early Paleocene.

Climate

The cooling trend of the last epoch of the Jurassic continued into the first age of the Cretaceous. There is evidence that snowfalls were common in the higher latitudes and the tropics became wetter than during the Triassic and Jurassic.[12] Glaciation was however restricted to high-latitude mountains, though seasonal snow may have existed farther from the poles. Rafting by ice of stones into marine environments occurred during much of the Cretaceous but evidence of deposition directly from glaciers is limited to the Early Cretaceous of the Eromanga Basin in southern Australia.[13][14]

After the end of the first age, however, temperatures increased again, and these conditions were almost constant until the end of the period.[12] The warming may have been due to intense volcanic activity which produced large quantities of carbon dioxide. Between 70–69 Ma and 66–65 Ma, isotopic ratios indicate elevated atmospheric CO2 pressures with levels of 1000–1400 ppmV and mean annual temperatures in west Texas between 21 and 23 °C (70-73 °F). Atmospheric CO2 and temperature relations indicate a doubling of pCO2 was accompanied by a ~0.6 °C increase in temperature.[15] The production of large quantities of magma, variously attributed to mantle plumes or to extensional tectonics,[16] further pushed sea levels up, so that large areas of the continental crust were covered with shallow seas. The Tethys Sea connecting the tropical oceans east to west also helped to warm the global climate. Warm-adapted plant fossils are known from localities as far north as Alaska and Greenland, while dinosaur fossils have been found within 15 degrees of the Cretaceous south pole.[17] Nonetheless, there is evidence of Antarctic marine glaciation in the Turonian Age.[18]

A very gentle temperature gradient from the equator to the poles meant weaker global winds, which drive the ocean currents, resulted in less upwelling and more stagnant oceans than today. This is evidenced by widespread black shale deposition and frequent anoxic events.[8] Sediment cores show that tropical sea surface temperatures may have briefly been as warm as 42 °C (108 °F), 17 °C (31 °F) warmer than at present, and that they averaged around 37 °C (99 °F). Meanwhile, deep ocean temperatures were as much as 15 to 20 °C (27 to 36 °F) warmer than today's.[19][20]

Life

Flora

Flowering plants (angiosperms) spread during this period,[21] although they did not become predominant until the Campanian Age near the end of the period. Their evolution was aided by the appearance of bees; in fact, the development of angiosperms and insects is a good example of coevolution. The first representatives of many leafy trees, including figs, planes and magnolias, appeared in the Cretaceous.[citation needed]

At the same time, some earlier Mesozoic gymnosperms continued to thrive, pehuéns (monkey puzzle trees, Araucaria) and other conifers being notably plentiful and widespread. Some fern orders, such as Gleicheniales, appeared as early in the fossil record as the Cretaceous and achieved an early broad distribution.[22] Gymnosperm taxa like Bennettitales and Hirmeriella died out before the end of the period.[23]

Terrestrial fauna

On land, mammals were generally small sized, but a very relevant component of the fauna, with cimolodont multituberculates outnumbering dinosaurs in some sites.[24] Neither true marsupials nor placentals existed until the very end,[25] but a variety of non-marsupial metatherians and non-placental eutherians had already begun to diversify greatly, ranging as carnivores (Deltatheroida), aquatic foragers (Stagodontidae) and herbivores (Schowalteria, Zhelestidae). Various "archaic" groups like eutriconodonts were common in the Early Cretaceous, but by the Late Cretaceous northern mammalian faunas were dominated by multituberculates and therians, with dryolestoids dominating South America.

The apex predators were archosaurian reptiles, especially dinosaurs, which were at their most diverse stage. Pterosaurs were common in the early and middle Cretaceous, but as the Cretaceous proceeded they declined for poorly understood reasons (once thought to be due to competition with early birds, but now it is understood avian adaptive radiation is not consistent with pterosaur decline[26]), and by the end of the period only two highly specialized families remained.

The Liaoning lagerstätte (Chaomidianzi formation) in China is a treasure chest of preserved remains of numerous types of small dinosaurs, birds and mammals, that provides a glimpse of life in the Early Cretaceous. The coelurosaur dinosaurs found there represent types of the group Maniraptora, which includes modern birds and their closest non-avian relatives, such as dromaeosaurs, oviraptorosaurs, therizinosaurs, troodontids along with other avialans. Fossils of these dinosaurs from the Liaoning lagerstätte are notable for the presence of hair-like feathers.

Insects diversified during the Cretaceous, and the oldest known ants, termites and some lepidopterans, akin to butterflies and moths, appeared. Aphids, grasshoppers and gall wasps appeared.[27]

-

Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the largest land predators of all time, lived during the late Cretaceous.

-

Up to 2 m long and 0.5 m high at the hip, Velociraptor was feathered and roamed the late Cretaceous.

-

Triceratops, one of the most recognizable genera of the Cretaceous

-

Confuciusornis, a genus of crow-sized birds from the Early Cretaceous

Marine fauna

In the seas, rays, modern sharks and teleosts became common.[28] Marine reptiles included ichthyosaurs in the early and mid-Cretaceous (becoming extinct during the late Cretaceous Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event), plesiosaurs throughout the entire period, and mosasaurs appearing in the Late Cretaceous.

Baculites, an ammonite genus with a straight shell, flourished in the seas along with reef-building rudist clams. The Hesperornithiformes were flightless, marine diving birds that swam like grebes. Globotruncanid Foraminifera and echinoderms such as sea urchins and starfish (sea stars) thrived. The first radiation of the diatoms (generally siliceous shelled, rather than calcareous) in the oceans occurred during the Cretaceous; freshwater diatoms did not appear until the Miocene.[27] The Cretaceous was also an important interval in the evolution of bioerosion, the production of borings and scrapings in rocks, hardgrounds and shells.

-

A scene from the early Cretaceous: a Woolungasaurus is attacked by a Kronosaurus.

-

Tylosaurus was a large mosasaur, carnivorous marine reptiles that emerged in the late Cretaceous.

-

Strong-swimming and toothed predatory waterbird Hesperornis roamed late Cretacean oceans.

-

The ammonite Discoscaphites iris, Owl Creek Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Ripley, Mississippi

-

A plate with Nematonotus sp., Pseudostacus sp. and a partial Dercetis triqueter, found in Hakel, Lebanon

-

Cretoxyrhina, one of the largest Cretaceous sharks, attacking a Pteranodon in the Western Interior Seaway

End-Cretaceous extinction event

The impact of a large body with the Earth may have been the punctuation mark at the end of a progressive decline in biodiversity during the Maastrichtian Age of the Cretaceous Period. The result was the extinction of three-quarters of Earth's plant and animal species. The impact created the sharp break known as K–Pg boundary (formerly known as the K–T boundary). Earth's biodiversity required substantial time to recover from this event, despite the probable existence of an abundance of vacant ecological niches.[29]

Despite the severity of K-Pg extinction event, there was significant variability in the rate of extinction between and within different clades. Species which depended on photosynthesis declined or became extinct as atmospheric particles blocked solar energy. As is the case today, photosynthesizing organisms, such as phytoplankton and land plants, formed the primary part of the food chain in the late Cretaceous, and all else that depended on them suffered as well. Herbivorous animals, which depended on plants and plankton as their food, died out as their food sources became scarce; consequently, the top predators such as Tyrannosaurus rex also perished.[30] Yet only three major groups of tetrapods disappeared completely: the non-avian dinosaurs, the plesiosaurs and the pterosaurs. The other Cretaceous groups that did not survive into the Cenozoic era, the ichthyosaurs and last remaining temnospondyls and non-mammalian cynodonts were already extinct millions of years before the event occurred.[citation needed]

Coccolithophorids and molluscs, including ammonites, rudists, freshwater snails and mussels, as well as organisms whose food chain included these shell builders, became extinct or suffered heavy losses. For example, it is thought that ammonites were the principal food of mosasaurs, a group of giant marine reptiles that became extinct at the boundary.[31]

Omnivores, insectivores and carrion-eaters survived the extinction event, perhaps because of the increased availability of their food sources. At the end of the Cretaceous there seem to have been no purely herbivorous or carnivorous mammals. Mammals and birds which survived the extinction fed on insects, larvae, worms and snails, which in turn fed on dead plant and animal matter. Scientists theorise that these organisms survived the collapse of plant-based food chains because they fed on detritus.[32][29][33]

In stream communities, few groups of animals became extinct. Stream communities rely less on food from living plants and more on detritus that washes in from land. This particular ecological niche buffered them from extinction.[34] Similar, but more complex patterns have been found in the oceans. Extinction was more severe among animals living in the water column, than among animals living on or in the seafloor. Animals in the water column are almost entirely dependent on primary production from living phytoplankton, while animals living on or in the ocean floor feed on detritus or can switch to detritus feeding.[29]

The largest air-breathing survivors of the event, crocodilians and champsosaurs, were semi-aquatic and had access to detritus. Modern crocodilians can live as scavengers and can survive for months without food and go into hibernation when conditions are unfavorable, and their young are small, grow slowly, and feed largely on invertebrates and dead organisms or fragments of organisms for their first few years. These characteristics have been linked to crocodilian survival at the end of the Cretaceous.[32]

-

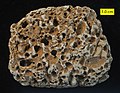

Numerous borings in a Cretaceous cobble, Faringdon, England; these are excellent examples of fossil bioerosion.

-

Rudist bivalves from the Cretaceous of the Omani Mountains, United Arab Emirates. Scale bar is 10 mm.

-

Inoceramus from the Cretaceous of South Dakota

See also

- Chalk Formation

- Cretaceous Thermal Maximum

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- South Polar region of the Cretaceous

- Western Interior Seaway

References

Notes

- ^ The term "Cretaceous" first appeared in English in: Henry Thomas De La Beche, A Geological Manual (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Carey & Lea, 1832). From page 35: "Group 4. (Cretaceous) contains the rocks which in England and the North of France are characterized by chalk in the upper part, and sands and sandstones in the lower."

Citations

- ^ "Cretaceous". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ d’Halloy, d’O., J.-J. (1822). "Observations sur un essai de carte géologique de la France, des Pays-Bas, et des contrées voisines" [Observations on a trial geological map of France, the Low Countries, and neighboring countries]. Annales des Mines. 7: 353–376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) From page 373: "La troisième, qui correspond à ce qu'on a déja appelé formation de la craie, sera désigné par le nom de terrain crétacé." (The third, which corresponds to what was already called the "chalk formation", will be designated by the name "chalky terrain".) - ^ Sovetskaya Enciklopediya [Great Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Russian) (3rd ed.). Moscow: Sovetskaya Enciklopediya. 1974. vol. 16, p. 50.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Glossary of Geology (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Geological Institute. 1972. p. 165.

- ^ Renne, Paul R.; et al. (2013). "Time scales of critical events around the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". Science. 339 (6120): 684–688. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1230492. PMID 23393261.

- ^ Vennari, Verónica V.; Lescano, Marina; Naipauer, Maximiliano; Aguirre-Urreta, Beatriz; Concheyro, Andrea; Schaltegger, Urs; Armstrong, Richard; Pimentel, Marcio; Ramos, Victor A. (2014). "New constraints on the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary in the High Andes using high-precision U–Pb data". Gondwana Research. 26 (1): 374–385. Bibcode:2014GondR..26..374V. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.07.005.

- ^ Jaramillo, Jessica. "Entrevista al Dr. Víctor Alberto Ramos, Premio México Ciencia y Tecnología 2013" (in Spanish).

Si logramos publicar esos nuevos resultados, sería el primer paso para cambiar formalmente la edad del Jurásico-Cretácico. A partir de ahí, la Unión Internacional de la Ciencias Geológicas y la Comisión Internacional de Estratigrafía certificaría o no, depende de los resultados, ese cambio.

- ^ a b Stanley 1999, pp. 481–482.

- ^ Dixon, Dougal; Benton, M J; Kingsley, Ayala; Baker, Julian (2001). Atlas of Life on Earth. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 215. ISBN 9780760719572.

- ^ Stanley 1999, p. 280.

- ^ Stanley 1999, pp. 279–281.

- ^ a b Kazlev, M.Alan. "Palaeos Mesozoic: Cretaceous: The Berriasian Age". Palaeos.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Alley, N. F.; Frakes, L. A. (2003). "First known Cretaceous glaciation: Livingston Tillite Member of the Cadna‐owie Formation, South Australia". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 50 (2): 139–144. Bibcode:2003AuJES..50..139A. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0952.2003.00984.x.

- ^ Frakes, L. A.; Francis, J. E. (1988). "A guide to Phanerozoic cold polar climates from high-latitude ice-rafting in the Cretaceous". Nature. 333 (6173): 547–549. Bibcode:1988Natur.333..547F. doi:10.1038/333547a0.

- ^ Nordt, Lee; Atchley, Stacy; Dworkin, Steve (December 2003). "Terrestrial Evidence for Two Greenhouse Events in the Latest Cretaceous". GSA Today. Vol. 13, no. 12. doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2003)013<4:TEFTGE>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Foulger, G.R. (2010). Plates vs. Plumes: A Geological Controversy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6148-0.

- ^ Stanley 1999, p. 480–482.

- ^ Bornemann, Norris RD; Friedrich, O; Beckmann, B; Schouten, S; Damsté, JS; Vogel, J; Hofmann, P; Wagner, T (Jan 2008). "Isotopic evidence for glaciation during the Cretaceous supergreenhouse". Science. 319 (5860): 189–92. Bibcode:2008Sci...319..189B. doi:10.1126/science.1148777. PMID 18187651.

- ^ "Warmer than a Hot Tub: Atlantic Ocean Temperatures Much Higher in the Past" PhysOrg.com. Retrieved 12/3/06.

- ^ Skinner & Porter 1995, p. 557.

- ^ Coiro, Mario; Doyle, James A.; Hilton, Jason (2019-01-25). "How deep is the conflict between molecular and fossil evidence on the age of angiosperms?". New Phytologist. 223 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1111/nph.15708. PMID 30681148.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Fern. Encyclopedia of Earth. National council for Science and the Environment Archived November 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Washington, DC

- ^ "Introduction to the Bennettitales". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia; Cifelli, Richard L.; Luo, Zhe-Xi (2005). Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure. Columbia University Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780231119184.

- ^ Halliday, Thomas John Dixon; Upchurch, Paul; Goswami, Anjali (29 June 2016). "Eutherians experienced elevated evolutionary rates in the immediate aftermath of the Cretaceous–Palaeogene mass extinction". Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 (1833): 20153026. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.3026. PMC 4936024. PMID 27358361.

- ^ Wilton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691150611.

- ^ a b "Life of the Cretaceous". www.ucmp.Berkeley.edu. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "EVOLUTIONARY/GEOLOGICAL TIMELINE v1.0". www.TalkOrigins.org. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ a b c MacLeod, N; Rawson, PF; Forey, PL; Banner, FT; Boudagher-Fadel, MK; Bown, PR; Burnett, JA; et al. (1997). "The Cretaceous–Tertiary biotic transition". Journal of the Geological Society. 154 (2): 265–292. Bibcode:1997JGSoc.154..265M. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.154.2.0265.

- ^ Wilf, P; Johnson KR (2004). "Land plant extinction at the end of the Cretaceous: a quantitative analysis of the North Dakota megafloral record". Paleobiology. 30 (3): 347–368. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0347:LPEATE>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Kauffman, E (2004). "Mosasaur Predation on Upper Cretaceous Nautiloids and Ammonites from the United States Pacific Coast". PALAIOS. 19 (1): 96–100. Bibcode:2004Palai..19...96K. doi:10.1669/0883-1351(2004)019<0096:MPOUCN>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Shehan, P; Hansen, TA (1986). "Detritus feeding as a buffer to extinction at the end of the Cretaceous". Geology. 14 (10): 868–870. Bibcode:1986Geo....14..868S. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1986)14<868:DFAABT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Aberhan, M; Weidemeyer, S; Kieesling, W; Scasso, RA; Medina, FA (2007). "Faunal evidence for reduced productivity and uncoordinated recovery in Southern Hemisphere Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary sections". Geology. 35 (3): 227–230. Bibcode:2007Geo....35..227A. doi:10.1130/G23197A.1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Sheehan, PM; Fastovsky, DE (1992). "Major extinctions of land-dwelling vertebrates at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, eastern Montana". Geology. 20 (6): 556–560. Bibcode:1992Geo....20..556S. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1992)020<0556:MEOLDV>2.3.CO;2.

Bibliography

- Yuichiro Kashiyama; Nanako O. Ogawa; Junichiro Kuroda; Motoo Shiro; Shinya Nomoto; Ryuji Tada; Hiroshi Kitazato; Naohiko Ohkouchi (May 2008). "Diazotrophic cyanobacteria as the major photoautotrophs during mid-Cretaceous oceanic anoxic events: Nitrogen and carbon isotopic evidence from sedimentary porphyrin". Organic Geochemistry. 39 (5): 532–549. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2007.11.010.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Larson, Neal L; Jorgensen, Steven D; Farrar, Robert A; Larson, Peter L (1997). Ammonites and the other Cephalopods of the Pierre Seaway. Geoscience Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ogg, Jim (June 2004). "Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's)". Archived from the original on 16 July 2006.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ovechkina, M.N.; Alekseev, A.S. (2005). "Quantitative changes of calcareous nannoflora in the Saratov region (Russian Platform) during the late Maastrichtian warming event" (PDF). Journal of Iberian Geology. 31 (1): 149–165. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rasnitsyn, A.P.; Quicke, D.L.J. (2002). History of Insects. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4020-0026-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)—detailed coverage of various aspects of the evolutionary history of the insects. - Skinner, Brian J.; Porter, Stephen C. (1995). The Dynamic Earth: An Introduction to Physical Geology (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60618-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stanley, Steven M. (1999). Earth System History. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-2882-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taylor, P. D.; Wilson, M. A. (2003). "Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities". Earth-Science Reviews. 62 (1): 1–103. Bibcode:2003ESRv...62....1T. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00131-9.