Saint Louis Blues (song)

| "Saint Louis Blues" | |

|---|---|

Sheet music cover | |

| Song | |

| Published | 1914 |

| Genre | Blues |

| Songwriter(s) | W. C. Handy |

"Saint Louis Blues" (or "St. Louis Blues") is a popular American song composed by W. C. Handy in the blues style and published in September 1914. It was one of the first blues songs to succeed as a pop song and remains a fundamental part of jazz musicians' repertoire. Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Bessie Smith, Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Guy Lombardo, and the Boston Pops Orchestra are among the artists who have recorded it. The song has been called "the jazzman's Hamlet."[1]

The 1925 version sung by Bessie Smith, with Louis Armstrong on cornet, was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1993. The 1929 version by Louis Armstrong & His Orchestra (with Red Allen) was inducted in 2008.

History

Handy said he had been inspired by a chance meeting with a woman on the streets of St. Louis distraught over her husband's absence, who lamented, "Ma man's got a heart like a rock cast in de sea", a key line of the song.[2][3] Handy's autobiography recounts his hearing the tune in St. Louis in 1892: "It had numerous one-line verses and they would sing it all night."[4]

The song was a massive and enduring success. At the time of his death in 1958, Handy was earning royalties of upwards of US$25,000 annually for the song (equivalent to $264,000 in 2023).[citation needed] The original published sheet music is available online from the United States Library of Congress in a searchable database of African-American music from Brown University.[5][6]

Analysis

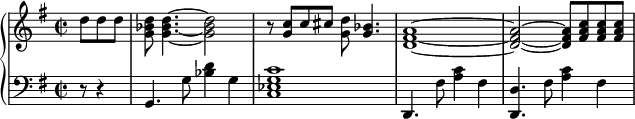

The form is unusual in that the verses are the now-familiar standard twelve-bar blues in common time with three lines of lyrics, the first two lines repeated, but it also has a 16-bar bridge written in the habanera rhythm, which Jelly Roll Morton called the "Spanish tinge" and characterized by Handy as tango.[7] The tango-like rhythm is notated as a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note and two quarter notes, with no slurs or ties. It is played in the introduction and in the sixteen-measure bridge.[5]

While blues often became simple and repetitive in form, "Saint Louis Blues" has multiple complementary and contrasting strains, similar to classic ragtime compositions. Handy said his objective in writing the song was "to combine ragtime syncopation with a real melody in the spiritual tradition."[8] T-Bone Walker commented about the song, "You can't dress up the blues... I'm not saying that 'Saint Louis Blues' isn't fine music you understand. But it just isn't blues".[9]

With traditional New Orleans and New Orleans–style bands, the tune is one of a handful that includes a set traditional solo. The clarinet solo, with a distinctive series of rising partials, was first recorded by Larry Shields with the Original Dixieland Jass Band in 1921. It is not found on any earlier recordings or published orchestrations of the tune. Shields is often credited with creating this solo, but claims have been made for other early New Orleans clarinetists, including Emile Barnes.

Performances

| "Saint Louis Blues" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Bessie Smith | |

| Released | 1925 |

| Recorded | New York City, January 14, 1925 |

| Genre | Blues |

| Length | 3:11 |

| Label | Columbia |

| Songwriter(s) | W. C. Handy |

Writing about the first time "Saint Louis Blues" was played (1914),[10] Handy noted that

The one-step and other dances had been done to the tempo of Memphis Blues ... When St Louis Blues was written the tango was in vogue. I tricked the dancers by arranging a tango introduction, breaking abruptly into a low-down blues. My eyes swept the floor anxiously, then suddenly I saw lightning strike. The dancers seemed electrified. Something within them came suddenly to life. An instinct that wanted so much to live, to fling its arms to spread joy, took them by the heels.[7]

Singer and actress Ethel Waters was the first woman to sing "Saint Louis Blues" in public.[11] Historians Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff state that the first male singer to perform "Saint Louis Blues" was Charles Anderson, a popular female impersonator of the day who included the song in his act as early as October 1914, the year Handy issued the song.[citation needed] This backs the claim by Waters, who said she learned it from Anderson and featured it herself during a 1917 engagement in Baltimore.[11][12]

Researcher Guy Marco, in his Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound in the United States, stated that the first audio recording of "Saint Louis Blues" was by Al Bernard in July 1918 for Vocalion Records. However, the house band at Columbia Records, directed by Charles A. Prince, released an instrumental version in December 1915. Bernard's version may have been the first U.S. issue to include the lyrics, but Ciro's Club Coon Orchestra, a group of black American artists appearing in Britain, had already recorded a version including the lyrics in September 1917.[citation needed]

The film St. Louis Blues, from 1929, featured Bessie Smith singing the song.[13]

Cover versions

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: versions may not meet WP:SONGCOVER. (March 2019) |

- Prince's Orchestra (1916)[14]

- Al Bernard (1919)[14]

- Marion Harris (1920)[14]

- Original Dixieland Jazz Band (1921)[14]

- W. C. Handy (1923)[15]

- Bessie Smith with Louis Armstrong (1925)[15][16]

- Fats Waller (1926)[15]

- Al Bernard as "John Bennett" (Madison, 1928)[17]

- Katherine Henderson with Clarence Williams and His Orchestra (1928)[18][19]

- Louis Armstrong (1929)[15]

- Cab Calloway (1930)[15]

- Rudy Vallee (1930)[14]

- The Mills Brothers (1932)[14]

- Bing Crosby with Duke Ellington and His Orchestra (recorded February 11, 1932)[20]

- Paul Robeson, recorded in London on February 20, 1934 and released by the His Master's Voice (1934)

- The Boswell Sisters – The Boswell Sisters Collection 1925–36 (1935)[21]

- Benny Goodman (1936)[14]

- Django Reinhardt (1937)[15]

- Die Goldene Sieben (1937)[22]

- Guy Lombardo (1939)[14]

- Earl Hines (1940)[15]

- Billie Holiday with Benny Carter – The Great American Songbook (1940)[23]

- Billy Eckstine – Everything I Have Is Yours (1947)[24]

- Art Tatum, Piano Starts Here (1949)[25]

- Dizzy Gillespie (1949)[15]

- Chet Atkins – Chet Atkins' Gallopin' Guitar (1952)[26]

- Louis Armstrong – Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy (1954)[15]

- Gil Evans with Cannonball Adderley – New Bottle Old Wine (1958)[15]

- Dizzy Gillespie – Have Trumpet, Will Excite! (1959)[27]

- Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges, Back to Back (1959)[28]

- Red Garland – Red in Bluesville (1959)[29]

- Pete Seeger - American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 3 (1959)[30]

- Duane Eddy - The Twangs The Thang (1959)

- Dave Brubeck – At Carnegie Hall(1963)[15]

- Chuck Berry – Chuck_Berry_in_London (1965)

- Illinois Jacquet – The Soul Explosion (1968)[31]

- The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra – Monday Night (1968)[15]

- Eumir Deodato – Artistry (1974)[32]

- Ray Bryant – Solo Flight (1976)[33]

- George Wright – Red Hot and Blue(1984)[34]

- Emmett Miller – Minstrel Man from Georgia (1996)[35]

- Herbie Hancock with Stevie Wonder – Gershwin's World(1998)[15]

- David Sanborn – Here & Gone (2008)[36]

- Hugh Laurie – Didn't It Rain (2013)[37]

Inspiration for the NHL's St. Louis Blues

The St. Louis Blues of the National Hockey League (NHL) are named after the titular song.

See also

Notes

- ^ Stanfield, Peter (2005). Body and Soul: Jazz and Blues in American Film, 1927-63. University of Illinois Press. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-0-252-02994-3. Retrieved 12 April 2005.

- ^ Tom Morgan, "St. Louis Blues: An American Classic", Bluesnet, April 8, 2004. (Retrieved from web.archive.net 2018-05-28.)

- ^ Handy 1941, p. 119

- ^ Handy 1941, p. 147

- ^ a b "American Memory from the Library of Congress – List All Collections". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ^ Handy, W. C. (William Christopher), "The 'St. Louis blues'" (1918). African American Sheet Music. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. (Retrieved 2018-05-28.)

- ^ a b Handy 1941, pp. 99–100

- ^ Handy 1941, p. 120

- ^ Giles Oakley (1997). The Devil's Music. Da Capo Press. p. 42/3. ISBN 978-0-306-80743-5.

- ^ Handy 1941, p. 305

- ^ a b Britannica, Encyclopedia (May 31, 2017). "Ethel Waters: American Singer and Actress". www.britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Freeland, David (1 July 2009). "Behind the Song: "St. Louis Blues"". American Songwriter. Retrieved 28 October 2016.(subscription required)

- ^ Albertson, Chris (2003). Bessie (Revised ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Whitburn, Joel (1986). Pop Memories: 1890–1954. p. 584.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gioia, Ted (2012). The Jazz Standards. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-0-19-993739-4.

- ^ Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 12. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- ^ Ginell, Cary (1994). Milton Brown and the Founding of Western Swing. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press. pp. 245–246. ISBN 0-252-02041-3.

- ^ "Clarence Williams & the Blues Singers Vol 2 1927–1932". Document-records.com. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- ^ "Katherine Henderson Songs". Allmusic. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- ^ "A Bing Crosby Discography". BING magazine. International Club Crosby. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ "The Boswell Sisters Collection 1925–36". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Die Goldene Sieben: St. Louis Blues; Berlin, 11 November 1937, Electrola EG6132, Matrize ORA2384-1

- ^ "The Great American Songbook". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Everything I Have Is Yours". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Piano Starts Here". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Chet Atkins' Gallopin' Guitar". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Lankford Jr., Ronnie D. "Have Trumpet, Will Excite!". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Chadbourne, Eugene. "Back to Back: Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges Play the Blues". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Red in Bluesville". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "American Favorite Ballads, Vol.3". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "The Soul Explosion". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Ginell, Richard S. "Artistry". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Solo Flight". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ DeLay, Tom (January 1985). "For the Records". Theatre Organ. 27 (1): 19. ISSN 0040-5531.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Minstrel Man from Georgia". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Widran, Jonathan. "Here & Gone". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Didn't It Rain". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

References

- Handy, W. C. (1941). Bontemps, Arna Wendell (ed.). Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. New York City: Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help).

External links

- 1914 songs

- Music of St. Louis

- Original Dixieland Jass Band songs

- Nat King Cole songs

- Louis Armstrong songs

- Cab Calloway songs

- LaVern Baker songs

- 1910s jazz standards

- Songs about cities in the United States

- Songs with music by W. C. Handy

- Benny Goodman songs

- Blues songs

- Bessie Smith songs

- Billie Holiday songs

- Lena Horne songs

- Mildred Bailey songs

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist(s)

- Jazz compositions in G major

- Songs about Missouri

- Songs composed in G major