Triad (organized crime)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A triad is a Chinese transnational organized crime syndicate based in Greater China and has outposts in various countries with significant overseas Chinese populations.

The Hong Kong triad is distinct from mainland Chinese criminal organizations. In ancient China, the triad was one of three major secret societies.[2] It established branches in Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities overseas.[3] Known as "mainland Chinese criminal organizations", they are of two major types: dark forces (loosely-organized groups) and black societies (more-mature criminal organizations). Two features which distinguish a black society from a dark force are the ability to achieve illegal control over local markets, and receiving police protection.[4] The Hong Kong triad refers to traditional criminal organizations operating in (or originating from) Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and south-east Asian countries and regions, while organized-crime groups in mainland China are known as "mainland Chinese criminal groups".

Etymology

| Sanhehui | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 三合會 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三合会 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Three Harmonies Society | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "triad" is a translation of the Chinese term San Ho Hui (or Triple Union Society), referring to the union of heaven, earth and humanity.[5] Another theory posits that the word "triad" was coined by British authorities in colonial Hong Kong as a reference to the triads' use of triangular imagery.[6] It has been speculated that triad organizations took after, or were originally part of, revolutionary movements such as the White Lotus,[7] the Taiping and Boxer Rebellions and the Heaven and Earth Society.

The generic use of the word "triads" for all Chinese criminal organizations is imprecise; triad groups are geographically, ethnically, culturally and structurally unique. "Triads" are traditional organized-crime groups originating from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.[3] Criminal organizations operating in, or originating from, mainland China are "mainland Chinese criminal groups" or "black societies".[2] After years of repression, only some elements of triad groups are involved with illegal activities. Triads in Hong Kong are less involved with "traditional" criminal activity and are becoming associated with white-collar crime; traditional initiation ceremonies rarely take place to avoid official attention. Rumors have it that triads have now migrated to the U.S and all groups and factions have now joined and aligned themselves as one large group. There are no longer any separations with rivals or groups, including United Bamboo and 14k.[8] Triads are a chord of 3 tones, each tone a third apart (root, 3rd, and 5th)

History

Origins

Triad, a China-based criminal organization, secret association or club, was a branch of the secret Hung Society. The society was fragmented, and one group (known as the Triad and the Ching Gang) became a criminal organization. After the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, secret societies in mainland China were suppressed in campaigns ordered by Mao Zedong. Most Chinese secret societies, including the triads and some of the remaining Ching Gang, relocated to British-controlled Hong Kong, Taiwan, Southeast Asia and overseas countries (particularly the US) and competed with the Tong and other Chinese secret societies. Gradually, Chinese secret societies turned to drugs and extortion for income.[9]

18th century

The Heaven and Earth Society (天地會, Tiandihui), a fraternal organization, was founded during the 1760s. As the society's influence spread throughout China, it branched into several smaller groups with different names; one was the Three Harmonies Society (三合會, Sanhehui). These societies adopted the triangle as their emblem, usually accompanied by decorative images of swords or portraits of Guan Yu.

19th century

British Hong Kong was intolerant of secret societies, and the British considered the triads a criminal threat. Triads were charged and imprisoned under British law.

During the 19th century, many such societies were seen as legitimate ways of helping immigrants from China settle into a new country. Secret societies were banned by the British government in Singapore during the 1890s, and slowly reduced in number by successive colonial governors and leaders. Facilitating the origins of Singapore gangs, the opium trade, prostitution and brothels were also banned. Immigrants were encouraged to seek help from a local kongsi instead of turning to secret societies, which contributed to the societies' decline.

20th century

After World War II, the secret societies saw a resurgence as gangsters took advantage of uncertainty and growing anti-British sentiment. Some Chinese communities, such as "new villages" in Kuala Lumpur and Bukit Ho Swee in Singapore, became notorious for gang violence. When the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949 in mainland China, law enforcement became stricter and a government crackdown on criminal organizations forced the triads to migrate to British Hong Kong. An estimated 300,000 triad members lived in Hong Kong during the 1950s. According to the University of Hong Kong, most triad societies were established between 1914 and 1939 and there were once more than 300 in the territory. The number of groups has consolidated to about 50, of which 14 are under police surveillance. There were nine main triads operating in Hong Kong. They divided land by ethnic group and geographic locations, with each triad in charge of a region. The triads were Wo Hop To, Wo Shing Wo, Rung, Tung, Chuen, Shing, Sun Yee On, 14K and Luen. Each had a headquarters, sub-societies and public image. After the 1956 riots, the Hong Kong government introduced stricter law enforcement and the triads became less active.

21st century

On 18 January 2018, Italian police arrested 33 people connected to a Chinese triad operating in Europe as part of its Operation China Truck (which began in 2011). The triad were active in Tuscany, Veneto, Rome and Milan in Italy, and in France, Spain and the German city of Neuss. The indictment accuses the Chinese triad of extortion, usury, illegal gambling, prostitution and drug trafficking. The group was said to have infiltrated the transport sector, using intimidation and violence against Chinese companies wishing to transport goods by road into Europe.[10] Police seized several vehicles, businesses, properties and bank accounts.[11]

Criminal activities

Triads engage in a variety of crimes, from fraud, extortion and money laundering to trafficking and prostitution, and are involved in smuggling and counterfeiting goods such as music, video, software, clothes, watches and money.[12]

Drug trafficking

Since the first opium bans during the 19th century, Chinese criminal gangs have been involved in worldwide illegal drug trade. Many triads switched from opium to heroin, produced from opium plants in the Golden Triangle, refined into heroin in China and trafficked to North America and Europe, in the 1960s and 1970s. The most important triads active in the international heroin trade are the 14K and the Tai Huen Chai. Triads have begun smuggling chemicals from Chinese factories to North America (for the production of methamphetamine), and to Europe for the production of MDMA. Triads in the United States also traffic large quantities of ketamine.

Counterfeiting

Triads have been engaging in counterfeiting since the 1880s. During the 1960s and 1970s, they were involved in counterfeiting currency (often the Hong Kong 50-cent piece). The gangs were also involved in counterfeiting expensive books for sale on the black market. With the advent of new technology and the improvement of the average standard of living, triads produce counterfeit goods such as watches, film VCDs and DVDs and designer apparel such as clothing and handbags.[13] Since the 1970s, triad turf control was weakened and some shifted their revenue streams to legitimate businesses.[14]

Health care fraud

In 2012, four triad members were arrested for health care fraud in Japan.[15]

Structure and composition

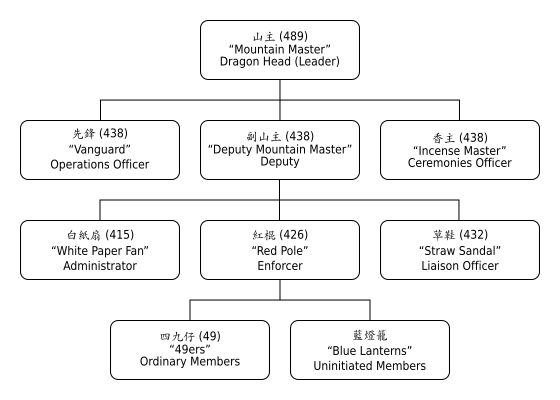

Triads use numeric codes to distinguish ranks and positions within the gang; the numbers are inspired by Chinese numerology and based on the I Ching.[16] The Mountain (or Dragon Master or Dragon Head) is 489, 438 is the Deputy Mountain Master, 432 indicates Straw Sandal rank;[17] the Mountain Master's proxy, Incense Master (who oversees inductions into the triad), and Vanguard 438/2238 (who assists the Incense Master). Law enforcement and intel have it that the Vanguard may actually hold the highest power or final word. A military commander (also known as a Red Pole), overseeing defensive and offensive operations, is 426; 49 denotes a soldier, or rank-and-file member. The White Paper Fan (415) provides financial and business advice, and the Straw Sandal (432) is a liaison between units.[18][19] An undercover law-enforcement agent or spy from another triad is 25, also popular Hong Kong slang for an informant. Blue Lanterns are uninitiated members, equivalent to Mafia associates, and do not have a designating number. According to De Leon Petta Gomes da Costa, who interviewed triads and authorities in Hong Kong, most of the current structure is a vague, low hierarchy; the traditional ranks and positions no longer exist.[8]

Rituals and codes of conduct

Similar to the Indian thuggees or the Japanese yakuza, triad members participate in initiation ceremonies.[20] A typical ceremony takes place at an altar dedicated to Guan Yu, with incense and an animal sacrifice (usually a chicken, pig or goat). After drinking a mixture of wine and blood (from the animal or the candidate), the member passes beneath an arch of swords while reciting the triad's oaths. The paper on which the oaths are written will be burnt on the altar to confirm the member's obligation to perform his duties to the gods. Three fingers of the left hand are raised as a binding gesture.[21] The triad initiate is required to adhere to 36 oaths.[22]

Clans

Based in Hong Kong

The most powerful triads based in Hong Kong are:

Based elsewhere

Many triads emigrated to Taiwan and Chinese communities worldwide:

- Bamboo Union, Taiwan

- Four Seas Gang, Taiwan

- Tien Tao Meng, Taiwan

- Song Lian Gang, Taiwan

- Lo Fu-chu, Taiwan

- Sio Sam Ong, Malaysia

- Ang Soon Tong, Singapore

- Wah Kee, Singapore

- Ghee Hin Kongsi, Singapore

- Ping On, Boston

- Wah Ching, San Francisco

- Black Dragons, Los Angeles

- Flying Dragons, New York City

- Ghost Shadows, New York City

- Green Dragons, New York City

- White Tigers, New York City

- Ah Kong, Amsterdam, Bangkok

- Black Jade, Texas

- The Company, Australia, Macau [23]

Tongs

Similar to triads, Tongs originated independently in early immigrant Chinatown communities. The word means "social club", and tongs are not specifically underground organizations. The first tongs formed during the second half of the 19th century among marginalized members of early immigrant Chinese-American communities for mutual support and protection from nativists. Modeled on triads, they were established without clear political motives and became involved in criminal activities such as extortion, illegal gambling, drug and human trafficking, murder and prostitution.[24][25]

Southeast Asia

Triads were also active in Chinese communities throughout Southeast Asia. When Malaysia and Singapore (with the region's largest population of ethnic Chinese) became crown colonies, secret societies and triads controlled local communities by extorting protection money and illegal money lending. Many conducted blood rituals, such as drinking one another's blood, as a sign of brotherhood; others ran opium dens and brothels.

Remnants of these former gangs and societies still exist. Due to government efforts in Malaysia and Singapore to reduce crime, the societies have largely faded from the public eye (particularly in Singapore).

Triads were also common in Vietnamese cities with large Chinese (especially Cantonese and Teochew) communities. During the French colonial period, many businesses and wealthy residents in Saigon (particularly in the Chinatown district) and Haiphong were controlled by protection-racket gangs.

With Vietnamese independence in 1945, organized crime activity was drastically reduced as Ho Chi Minh's governments purged criminal activity in the country. According to Ho, abolishing crime was a method of protecting Vietnam and its people.[26] During the First Indochina War, Ho's police forces concentrated on protecting people in his zone from crime; the French cooperated with criminal organisations to fight the Viet Minh.[27] In 1955, President Ngô Đình Diệm ordered the South Vietnamese military to disarm and imprison organized-crime groups in the Saigon-Gia Định-Biên Hòa-Vũng Tàu region and cities such as Mỹ Tho and Cần Thơ in the Mekong Delta. Diem banned brothels, massage parlours, casinos and gambling houses, opium dens, bars, drug houses and nightclubs, all establishments frequented by the triads. However, Diệm allowed criminal activity to finance his attempts to eliminate the Viet Minh in the south.[28] Law enforcement was stricter in the north, with stringent control and monitoring of criminal activities. The government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam purged and imprisoned organized criminals, including triads, in the Haiphong and Hanoi areas. With pressure from Ho Chi Minh's police, Triad affiliates had to choose between elimination or legality. During the Vietnam War, the triads were eliminated in the north; in the south, Republic of Vietnam corruption protected their illegal activities and allowed them to control US aid. During the 1970s and 1980s, all illegal Sino-Vietnamese activities were eliminated by the Vietnamese police. Most triads were compelled to flee to Taiwan, Hong Kong or other countries in Southeast Asia.[29]

International activities

Triads are also active in other regions with significant overseas-Chinese populations: Macau, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the United States, Canada, Japan, Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Brazil, Peru and Argentina. They are often involved in migrant smuggling. Shanty and Mishra (2007) estimate that the annual profit from narcotics is $200 billion, and annual revenues from human trafficking into Europe and the United States are believed to amount to $3.5 billion.[30]

In Australia, the major importer of illicit drugs in recent decades has been 'The Company', according to police sources in the region. This is a conglomerate run by triad bosses which focuses particularly on methamphetamine and cocaine. It has laundered money through junkets for high-stakes gamblers who visit Crown Casinos in Australia and Macau. [23]

Countermeasures

Law enforcement

Hong Kong

The Organized Crime and Triad Bureau (OCTB) is the division of the Hong Kong Police Force responsible for triad countermeasures. The OCTB and the Criminal Intelligence Bureau work with the Narcotics and Commercial Crime Bureaus to process information to counter triad leaders. Other involved departments include the Customs and Excise Department, the Immigration Department and the Independent Commission Against Corruption. They cooperate with the police to impede the expansion of triads and other organized gangs.[31] Police actions regularly target organised crime, including raids on triad-controlled entertainment establishments and undercover work.[14] The journal Foreign Policy reported in its August 2019 edition, triad involvement in the Hong Kong protests.[32]

Canada

The Guns and Gangs Unit of the Toronto Police Service is responsible for handling triads in the city. The Asian Gang Unit of the Metro Toronto Police was formerly responsible for dealing with triad-related matters, but a larger unit was created to deal with the broad array of ethnic gangs.

At the national (and, in some cases, provincial) level, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police's Organized Crime Branch is responsible for investigating gang-related activities (including triads). The Canada Border Services Agency Organized Crime Unit works with the RCMP to detain and remove non-Canadian triad members. Asian gangs are found in many cities, primarily Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton.

The Organized Crime and Law Enforcement Act provides a tool for police forces in Canada to handle organized criminal activity. The act enhances the general role of the Criminal Code (with amendments to deal with organized crime) in dealing with criminal triad activities. Asian organized-crime groups were ranked the fourth-greatest organized-crime problem in Canada, behind outlaw motorcycle clubs, aboriginal crime groups and Indo-Canadian crime groups.

In 2011, it was estimated that criminal gangs associated with triads controlled 90 percent of the heroin trade in Vancouver, British Columbia.[33] Due to its geographic and demographic characteristics, Vancouver is the point of entry into North America for much of the heroin produced in Southeast Asia (much of the trade controlled by international organized-crime groups associated with triads). From 2006 to 2014, Southeast, East and South Asians accounted for 21 percent of gang deaths in British Columbia (trailing only Caucasians, who made up 46.3 percent of gang deaths.[34][35]

Legislation

Primary laws addressing triads are the Societies Ordinance and the Organized and Serious Crimes Ordinance. The former, enacted in 1949 to outlaw triads in Hong Kong, stipulates that any person convicted of being (or claiming to be) an officeholder or managing (or assisting in the management) of a triad can be fined up to HK$1 million and imprisoned for up to 15 years.[14]

The power of triads has also diminished due to the 1974 establishment of the Independent Commission Against Corruption. The commission targeted corruption in police departments linked with triads.[14] Being a member of a triad is an offence punishable by fines ranging from HK$100,000 to HK$250,000 and three to seven years imprisonment under an ordinance enacted in Hong Kong in 1994,[14] which aims to provide police with special investigative powers, provide heavier penalties for organized-crime activities and authorize the courts to confiscate the proceeds of such crimes.

Notable members

See also

- List of Chinese criminal organizations

- List of criminal enterprises, gangs and syndicates

- Organized crime

- Organised crime in Hong Kong

- Triads in the United Kingdom

- Secret societies in Singapore

- Tongs

- Chongqing gang trials

- Hong Kong action cinema:

- Sicilian Mafia

- Snakeheads (Chinese human-trafficking groups)

- Tiandihui

- Xiantiandao

- White Lotus

- Russian mafia

- Yakuza

- Sio Sam Ong

- Wan Kuok-koi

- Criminal tattoos

- Social problems in Chinatown

- Thuggee

Notes

- ^ "Hong Kong Triads and 'their' lucrative movie industry". gangstersinc.ning.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-10.

- ^ a b Wang, Peng (2017). The Chinese Mafia: Organized Crime, Corruption, and Extra-Legal Protection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198758402

- ^ a b Chu, Y. K. (2002). The triads as business. Routledge. ISBN 9780415757249

- ^ Wang, P. (2013). The rise of the Red Mafia in China: a case study of organized crime and corruption in Chongqing. Trends in Organized crime, 16(1), 49–73.

- ^ "British & World English: Definition of triad in English". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Gertz, in the Washington Times: "British authorities in colonial Hong Kong dubbed the groups triads because of the triangular imagery."

- ^ Triad Societies, p. 4

- ^ a b De Leon Petta Gomes da Costa (20 February 2017). "As Tríades e as Sociedades Secretas na China: Entre o mito e a desmistificação". Brazilian Journal of Social Sciences. 32 (93): 01. doi:10.17666/329309/2017. ISSN 1806-9053.

- ^ "Gangland- Deadly Triangle." Online video clip, YouTube. YouTube, 2008. Web. 21 Apr. 2016

- ^ "Italian police bust Chinese 'mafia' running rackets across Europe". The Local IT. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Italy arrests 33 'Chinese mafia' members". BBC. 18 January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Gertz, for the Washington Times. "Like other organized crime groups, triads [...] are engaged in a range of illegal activities such as bank and credit card fraud, currency counterfeiting, money laundering, extortion, human trafficking and prostitution." Triads rarely fight other ethnic mob groups, fighting mainly among themselves or against other triads. However triads were involved in some territorial disputes with the Irish mob, Jewish mafia and others.

- ^ M. Booth, The Dragon Syndicates; The Global Phenomenon of the Triads, Doubleday-Great Britain 1999, pp 386–400.

- ^ a b c d e Wong, Natalie (21 January 2011) "Dragons smell blood again" Archived 2014-10-10 at the Wayback Machine. The Standard

- ^ "big5.xinhuanet.com/gate/big5/news.xinhuanet.com/world/2012-11/14/c_123953295.htm - Translator". www.microsofttranslator.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Stephen L. Mallory, Understanding Organized Crime (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2007), page 137

- ^ Imran Kayani (15 November 2011). "ORGANIZED CRIME EPISODE 10 Triads". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Stephen L. Mallory, Understanding Organized Crime (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2007), pages 137–138

- ^ Secret Societies, page 167

- ^ Gertz, for the Washington Times. "Like other organized crime groups, triads have elaborate initiation ceremonies similar to those of the Italian mafia [...]"

- ^ "Feature Articles 378". AmericanMafia.com. Archived from the original on 2010-10-15. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ^ Wynne, Mervyn Llewelyn (1941). Triad Societies, Volume 5. ISBN 9780415243971. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27.

- ^ a b McKenzie, Nick; Toscano, Nick; Tobin, Grace (27 July 2019). "Crown casino's links to Asian organised crime exposed". WAtoday. Nine Entertainment. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ "The Mafia in New Jersey - Asian Organized Crime Groups - Tongs and Street Gangs - Asian Organized Crime Groups". www.mafianj.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Andrew Sekeres III, Institutionalization of the Chinese Tongs in Chicago's Chinatown Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine (accessed June 26, 2011)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Lịch sử Công an nhân dân - Công An Đà Nẵng". www.catp.danang.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ 24h, Tin Tức. "Hội Tam Hoàng: Một thời vùng vẫy trên đất Việt". 24h.com.vn. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Shanty, Frank; Mishra, Patit Paban Organized crime: from trafficking to terrorism, pg 138, Volume 2. ISBN 1576073378 ABC-CLIO (September 24, 2007)

- ^ Hong Kong – The Facts: Police

- ^ Palmer, James. "Why Is Hong Kong Erupting?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^ "Crime Heat Maps - Vancouver Police Department". vancouver.ca. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Hong Kong triads supply meth ingredients to Mexican drug cartels". scmp.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "14K Triad". unitedgangs.com. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Treverton, Gregory F.; Matthies, Carl; Cunningham, Karla J.; Gouka, Jeremiah; Ridgeway, Greg (31 October 2008). Film Piracy, Organized Crime, and Terrorism. Rand Corporation. ISBN 9780833046741. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Thestar.com". thestar.com.my. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Pqasb.pqarchiver.com". pqarchiver.com. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Guns and poses: inside the drug lords' deadly world," Archived 2018-04-27 at the Wayback Machine The Sydney Morning Herald (August 30, 2010). Retrieved 10 June 2013.

References

- Books (Triad societies)

- Bolton, Kingsley; Hutton, Christopher (2000). Triad societies: western accounts of the history, sociology and linguistics of Chinese secret societies. Taylor & Francis.

- Booth, Martin. The Dragon Syndicates: The Global Phenomenon of the Triads

- Mallory, Stephen L. (2007). Understanding Organized Crime. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Reynolds, John Lawrence (2006). Secret societies: inside the world's most notorious organizations. Arcade Publishing.

- Ter Haar, B. J. (1998), Ritual and Mythology of the Chinese Triads: Creating an Identity, Sinica Leidensia, vol. 43, ISBN 9789004110632

- Chu, Y. K. (2002). The triads as business. Routledge.

- Books (Black societies or criminal organizations in mainland China)

- Wang, Peng (2017). The Chinese Mafia: Organized Crime, Corruption, and Extra-Legal Protection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198758402

- News

- Gertz, Bill; "Organized-crime triads targeted," The Washington Times (Friday, April 30, 2010). Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Wong, Natalie; "Dragons smell blood again," The Standard (January 21, 2011). Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Government publication

- Hong Kong – The Facts: Police (PDF), Information Services Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, August 2010

Video

- "Gangland- Deadly Triangle." Online video clip, YouTube. YouTube, 2008. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

Further reading

- Books

- Lintner, Bertil. Blood Brothers: The Criminal Underworld of Asia. Allen & Unwin.

- Journal Papers

- Lo, T. Wing. "Beyond social capital: Triad organized crime in Hong Kong and China." British Journal of Criminology 50.5 (2010): 851–872.

- Wang, Peng. "The Increasing Threat of Chinese Organised Crime: national, regional and international perspectives", The RUSI Journal Vol. 158, No.4, (2013),pp. 6–18.

- Skarbek, D., & Wang, P. (2015). Criminal rituals. Global Crime, 16(4), 288–305

External links

- https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/organized-crime#Asian-TOC

- Stratfor: Organized Crime in China

- Research Gate: Black Societies and Triad-like Organised Crime in China

- United Nations: Transnational Organized Crime in East Asia and the Pacific

- U.S. Congress: Transnational Activities of Chinese Crime Organizations

- Havoscope: Black Market Crime in China

- Global Strategy: Chinese Organized Crime