Adagio for Strings

| Adagio for Strings | |

|---|---|

| by Samuel Barber | |

Samuel Barber, photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1944 | |

| Key | B♭ minor |

| Year | 1936 |

| Based on | Barber's String Quartet |

| Duration | About 8 minutes |

| Scoring | String orchestra |

| Audio sample | |

Thirty-second sample of Adagio for Strings | |

Adagio for Strings is a work by Samuel Barber, arguably his best known, arranged for string orchestra from the second movement of his String Quartet, Op. 11.

Barber finished the arrangement in 1936, the same year that he wrote the quartet. It was performed for the first time on November 5, 1938, by Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra in a radio broadcast from NBC Studio 8H. Toscanini also played the piece on his South American tour with the NBC Symphony in 1940.

Its reception was generally positive, with Alexander J. Morin writing that Adagio for Strings is "full of pathos and cathartic passion" and that it "rarely leaves a dry eye".[2] The music is the setting for Barber's 1967 choral arrangement of Agnus Dei. Adagio for Strings has been featured in many TV shows and movies, notably the 1986 American war drama film, Platoon.

History

Barber's Adagio for Strings was originally the second movement of his String Quartet, Op. 11, composed in 1936 while he was spending a summer in Europe with his partner Gian Carlo Menotti, an Italian composer who was a fellow student at the Curtis Institute of Music.[3] He was inspired by Virgil's Georgics. In the quartet, the Adagio follows a violently contrasting first movement (Molto allegro e appassionato) and is succeeded by music that opens with a brief reprise of the music from the first movement (marked Molto allegro (come prima) – Presto).[4]

In January 1938, Barber sent an orchestrated version of the Adagio for Strings to Arturo Toscanini. The conductor returned the score without comment, which annoyed Barber. Toscanini sent word through Menotti that he was planning to perform the piece and had returned it simply because he had already memorized it.[5] It was reported that Toscanini did not look at the music again until the day before the premiere.[6] On November 5, 1938, a selected audience was invited to Studio 8H in Rockefeller Center to watch Toscanini conduct the first performance; it was broadcast on radio and also recorded. Initially, the critical reception was positive, as seen in the review by The New York Times' Olin Downes. Downes praised the piece, but he was reproached by other critics who claimed that he overrated it.[7]

Toscanini conducted Adagio for Strings in South America and Europe, the first performances of the work on both continents. Over April 16–19, 1942, the piece had public performances by the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy at Carnegie Hall. Like the original 1938 performance, these were broadcast on radio and recorded.

Composition

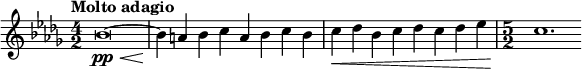

Adagio for Strings begins softly with a B♭ played by the first violins.

The lower strings come in two beats after the violins, which, as Johanna Keller from The New York Times put it, creates "an uneasy, shifting suspension as the melody begins a stepwise motion, like the hesitant climbing of stairs".[3] NPR Music said that "with a tense melodic line and taut harmonies, the composition is considered by many to be the most popular of all 20th-century orchestral works."[8] Thomas Larson remarked that the piece "evokes a deep sadness in those who hear it".[9] Many recordings of the piece have a duration of about eight minutes.[10] The work is largely in the key of B♭ minor.

The Adagio is an example of arch form and builds on a melody that first ascends and then descends in stepwise fashion. Barber subtly manipulates the basic pulse throughout the work by constantly changing time signatures including 4

2, 5

2, 6

2, and 3

2.[6] After four climactic chords and a long pause, the piece presents the opening theme again and fades away on an unresolved dominant chord.

Music critic Olin Downes wrote that the piece is very simple at climaxes but reasoned that the simple chords create significance for the piece. Downes went on to say: "That is because we have here honest music, by an honest musician, not striving for pretentious effect, not behaving as a writer would who, having a clear, short, popular word handy for his purpose, got the dictionary and fished out a long one."[7][11][12]

Critical reception

Alexander J. Morin, author of Classical Music: The Listener's Companion, said that the piece was "full of pathos and cathartic passion" and that it "rarely leaves a dry eye".[2] In 1938, Olin Downes noted that with the piece, Barber "achieved something as perfect in mass and detail as his craftsmanship permits."[11]

In an edition of A Conductor's Analysis of Selected Works, John William Mueller devoted over 20 pages to Adagio for Strings.[13] Wayne Clifford Wentzel, author of Samuel Barber: A Research and Information Guide (Composer Resource Manuals), said that it was a piece usually selected for a closing act because it was moderately famous. Roy Brewer, writer for AllMusic, said that it was one of the most recognizable pieces of American concert music.[14]

Arrangements

G. Schirmer has published several alternate arrangements for Adagio for Strings. They include:[15]

- Solo organ (1949) – William Strickland

- Clarinet choir (1964) – Lucien Cailliet

- Woodwind band (1967) – John O'Reilly

- Agnus Dei (1967) – Samuel Barber – Latin text setting of "Agnus Dei" (Lamb of God) for chorus with optional organ or piano accompaniment

Strickland, while assistant organist at St Bartholomew's Church in New York, had been impressed by Toscanini's recording of the work and had submitted his own arrangement for organ to Schirmers. After he made contact with Barber at a musical soirée in 1939, he learned that his transcription had received a lukewarm response from the composer. Strickland, subsequently appointed wartime director of music at the Army's Fort Myer in Virginia, became a champion of Barber's new compositions. He continued to correspond with the composer.

In 1945 Barber wrote to Strickland, expressing his dissatisfaction with previously proposed organ arrangements; he encouraged him to discuss and prepare his own version for publication.

Schirmers have had several organ arrangements submitted of my Adagio for Strings and many inquiries as to whether it exists for organ. I have always turned them down, as, I know little about the organ, I am sure your arrangement would be best. Have you got the one you did before, if not, would you be willing to make it anew? If so, will you ever be in N.Y. on leave, so I could discuss it with you and hear it? If it is done at all, I should like it done as well as possible, and this by you. They would pay you a flat fee for the arrangement, although I don't suppose it will be very much. However, that is their affair. Let me know what you think about it.[6]

Strickland, having kept the piece, sent his organ arrangement to G. Schirmer. The company published it in 1949.[6]

Legacy

The recording of the world premiere in 1938, with Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra, was selected in 2005 for permanent preservation in the National Recording Registry at the United States Library of Congress.[16] Since the 1938 recording, the Adagio for Strings has frequently been heard throughout the world, and it was one of the few American pieces to be played in the Soviet Union during the Cold War.[14]

The Adagio for Strings has been performed on many public occasions, especially during times of mourning. It was:

- Broadcast over radio at the announcement of Franklin D. Roosevelt's death;[17]

- Broadcast on television at the announcement of John F. Kennedy's death[18]

- Played at the funeral of Albert Einstein[18]

- Played at the funeral of Princess Grace of Monaco[17]

- Broadcast on BBC Radio several times after the announcement of the death of Princess Diana

- Performed at Last Night of the Proms in 2001 at the Royal Albert Hall to honor the memory of the victims of the September 11 attacks[19]

- Played during the 2010 Winter Olympics opening ceremony in Vancouver; the fatal crash of the luger Nodar Kumaritashvili on the same day added to the performance's emotional affect.[9]

- Played at the state funeral of Canadian Jack Layton, the New Democratic Party Leader[20]

- Played in Trafalgar Square, on January 9, 2015, by an ensemble of 150 string players led by Thomas Gould of the Aurora Orchestra following the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo.[21]

- Played at the National University of Singapore for the state funeral of Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore on 29 March 2015

- Played by the Brussels Philharmonic on March 25, 2016 in front of the Brussels Stock Exchange following the 2016 Brussels bombings earlier that week.[22]

- Played at the National University of Singapore for the state funeral of S. R. Nathan in Singapore on August 26, 2016

- Played in Blonia Park in Kraków on July 29, 2016, as the background music for the 12th Station of the Stations of the Cross during World Youth Day 2016.

- Played in Central Park in New York City on June 15, 2016, for the victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting.[23]

- Played at the televised memorial in Manchester, England on May 23, 2017, for the victims of the Manchester Arena bombing.[24]

- Played at the digital European Concert by Berlin Philharmonie on May 1, 2020, for the victims of the Coronavirus victims.[25]

Adagio for Strings is the final song on the 2010 Peter, Paul and Mary compilation album Peter Paul and Mary, With Symphony Orchestra. Mary Travers had requested that Adagio for Strings be played at her memorial service.[26]

The Adagio for Strings was one of John F. Kennedy's favorite pieces of music. Jackie Kennedy arranged a concert the Monday after his death with the National Symphony Orchestra; they played to an empty hall. The concert was broadcast by radio. Barber knew about these memorial occasions. He did a radio interview about it with WQXR and said, "They always play that piece. I wish they'd play some of my other pieces."[27]

In 2004, listeners of the BBC's Today program voted Adagio for Strings the "saddest classical" work ever, ahead of "Dido's Lament" from Dido and Aeneas by Henry Purcell, the Adagietto from Gustav Mahler's 5th symphony, Metamorphosen by Richard Strauss, and Gloomy Sunday as sung by Billie Holiday.[28][29]

In 2006 a recorded performance of this work by the London Symphony Orchestra was the highest-selling classical piece on iTunes.[30]

The musicologist Bill McGlaughlin compares its role in American music to the role that Edward Elgar's Enigma Variations: Variation IX "Nimrod" holds for the British.[31]

Adagio for Strings can be heard on many film, television, and game soundtracks.[32]

Adaptations

The work is extremely popular in the electronic dance music genre, notably in trance.[33] Artists who have covered it include William Orbit,[34] Ferry Corsten, Armin van Buuren,[35] Tiësto, Mark Sixma, Bastille, and Lucas & Steve.

An adaptation for erhu, piano and guitar was recorded by classical pianist and electronic music composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, and appears on the Japanese release for his 1989 album Beauty.

eRa included this song in their 2009 album Classics.[36]

References

- ^ Adagio for Strings by Cary O'Dell, Library of Congress, National Recording Registry

- ^ a b Morin, Alexander (2001). Classical Music: Third Ear: The Essential Listening Companion. Backbeat Books. p. 74. ISBN 0-87930-638-6.

- ^ a b Keller, Johanna (March 7, 2010). "An Adagio for Strings, and for the Ages". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Woodstra, Chris; Brennan, Gerald; Schrott, Allen (2005). All Music Guide to Classical Music: The Definitive Guide to Classical Music. Backbeat Books. p. 81. ISBN 0-87930-865-6.

- ^ "The Impact of Barber's Adagio for Strings". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. November 4, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2011. (Audio clip)

- ^ a b c d Heyman, Barbara B (1992). Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 167–180. ISBN 0-19-509058-6.

- ^ a b Tick, Judith; Beaudoin, Paul, eds. (2008). Music in the USA: a documentary companion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513987-9.

- ^ "The Impact of Barber's Adagio for Strings". NPR. November 4, 2006. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Larson, Thomas (2010). The Saddest Music Ever Written: The Story of Samuel Barber's "Adagio for Strings". Pegasus Books. ISBN 1-60598-115-X.

- ^ "Adagio for Strings, Samuel Barber". Schirmer.com. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Braun, Gene; McLanathan, Richard (1991). The Arts (Great Contemporary Issues Series). Ayer Co Pub. p. 132. ISBN 0-405-11153-3.

- ^ Downes, Olin (1968). Olin Downes on music: a selection from his writings during the half-century 1906 to 1955. Greenwood Publishing Group. ASIN B0006BYVRG.

- ^ Mueller, John William (1992). A conductor's analysis of selected works. John William Mueller. pp. 187–210.

- ^ a b "Adagio for Strings (or string quartet; arr. from 2nd mvt. of String Quartet), Op. 11". Allmusic. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Heyman, Barbara B (1992), Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-509058-6

- ^ "The National Recording Registry 2005". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ a b Lee, Douglas A. (2002). Masterworks of 20th Century Music: The Modern Repertory Of The Symphony Orchestra. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93846-5.

- ^ a b Daniel Felsenfeld (2005). Britten and Barber: Their Lives and Their Music. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 143. ISBN 1574671081.

- ^ Barnes, Anthony (September 16, 2001). "Tradition yields to compassion". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "In Photos: Canadian NDP Leader Jack Layton's procession, funeral".

- ^ "Professional musicians joined with amateur performers last night in Trafalgar Square, London, to remember the victims of the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris".

- ^ Van Den Steen, Stephanie (March 25, 2016). "Music Played after Brussels Attacks". La Libre. Video at Bottom, French Language. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uRS8O3nT4U

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nlJ5VAfF8Jc

- ^ https://www.digitalconcerthall.com/concert/53365

- ^ "Peter, Paul and Mary Soar Again with Symphony Orchestra". February 10, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "WQXR Features Barber's Adagio: The Saddest Piece Ever?". September 8, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ "Today: search for the world's saddest music". Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ "Saddest Music shortlist". Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (March 28, 2006). "Big demand for classical downloads is music to ears of record industry". Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ McGlaughlin, Bill. Edward Elgar: Part 2 of 5. Exploring Music. Originally aired 6 April 2004.

- ^ Samuel Barber at IMDb, listing of films using music by Barber, almost all the Adagio

- ^ Sansone, Glen (February 14, 2000). "William Orbit". CMJ New Music Report. CMJ: 20.

- ^ "Billboard Dance". Billboard: 87. October 10, 2005.

- ^ Jacks, Kelso (January 31, 2000). "Record News". CMJ New Music Report. CMJ: 11.

- ^ "Era Classics – Overview". Allmusic. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

External links

- Sample from the BBC

- NPR 100: Barber's Adagio

- The Impact of Barber's Adagio by All Things Considered

- Special on the selection of the 1938 broadcast debut of Adagio for Strings to the 2005 National Recording Registry

- Library of Congress essay on its selection for the 2005 National Recording Registry

- Barber's Adagio: Naked Expression of Emotion – audio report by NPR

- Agnus Dei, Barber's own choral setting performed a cappella by the Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge, conducted by Richard Marlow