Abortion-rights movement

Abortion-rights movements, also referred to as pro-choice movements or pro-abortion movements, advocate for legal access to induced abortion services. It is the argument against the pro-life movement. The issue of induced abortion remains divisive in public life, with recurring arguments to liberalize or to restrict access to legal abortion services. Abortion-rights supporters themselves are divided as to the types of abortion services that should be available and to the circumstances, for example different periods in the pregnancy such as late term abortions, in which access may be restricted.

Terminology

Many of the terms used in the debate are political framing terms used to validate one's own stance while invalidating the opposition's. For example, the labels "pro-choice" and "pro-life" imply endorsement of widely held values such as liberty and freedom, while suggesting that the opposition must be "anti-choice" or "anti-life" (alternatively "pro-coercion" or "pro-death").[1]

These views do not always fall along a binary; in one Public Religion Research Institute poll, they noted that the vagueness of the terms led to seven in ten Americans describing themselves as "pro-choice", while almost two-thirds described themselves as "pro-life".[2] It was found that, in polling, respondents would label themselves differently when given specific details about the circumstances around an abortion including factors such as rape, incest, viability of the fetus, and survivability of the mother.[3]

The Associated Press favors the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion" instead.[4]

Early history

Feminists of the late 19th century were often opposed to the legalization of abortion.[5][6] In The Revolution, operated by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, an anonymous contributor signing "A" wrote in 1869 about the subject, arguing that instead of merely attempting to pass a law against abortion, the root cause must also be addressed.

Simply passing an anti-abortion law would, the writer stated, "be only mowing off the top of the noxious weed, while the root remains. [...] No matter what the motive, love of ease, or a desire to save from suffering the unborn innocent, the woman is awfully guilty who commits the deed. It will burden her conscience in life, it will burden her soul in death; But oh! thrice guilty is he who drove her to the desperation which impelled her to the crime."[6][7][8][9]

United Kingdom

The movement towards the liberalization of abortion law emerged in the 1920s and 1930s in the context of the victories that had been recently won in the area of birth control. Campaigners including Marie Stopes in England and Margaret Sanger in the US had succeeded in bringing the issue into the open, and birth control clinics were established which offered family planning advice and contraceptive methods to women in need.

In 1929, the Infant Life Preservation Act was passed in the United Kingdom, which amended the law (Offences against the Person Act 1861) so that an abortion carried out in good faith, for the sole purpose of preserving the life of the mother, would not be an offence.[10]

Stella Browne was a leading birth control campaigner, who increasingly began to venture into the more contentious issue of abortion in the 1930s. Browne's beliefs were heavily influenced by the work of Havelock Ellis, Edward Carpenter and other sexologists.[11] She came to strongly believe that working women should have the choice to become pregnant and to terminate their pregnancy while they worked in the horrible circumstances surrounding a pregnant woman who was still required to do hard labour during her pregnancy.[12] In this case she argued that doctors should give free information about birth control to women that wanted to know about it. This would give women agency over their own circumstances and allow them to decide whether they wanted to be mothers or not.[13]

In the late 1920s Browne began a speaking tour around England, providing information about her beliefs on the need for accessibility of information about birth control for women, women's health problems, problems related to puberty and sex education and high maternal morbidity rates among other topics.[11] These talks urged women to take matters of their sexuality and their health into their own hands. She became increasingly interested in her view of the woman's right to terminate their pregnancies, and in 1929 she brought forward her lecture “The Right to Abortion” in front of the World Sexual Reform Congress in London.[11] In 1931 Browne began to develop her argument for women's right to decide to have an abortion.[11] She again began touring, giving lectures on abortion and the negative consequences that followed if women were unable to terminate pregnancies of their own choosing such as: suicide, injury, permanent invalidism, madness and blood-poisoning.[11]

Other prominent feminists, including Frida Laski, Dora Russell, Joan Malleson and Janet Chance began to champion this cause - the cause broke dramatically into the mainstream in July 1932 when the British Medical Association council formed a committee to discuss making changes to the laws on abortion.[11] On 17 February 1936, Janet Chance, Alice Jenkins and Joan Malleson established the Abortion Law Reform Association as the first advocacy organisation for abortion liberalization. The association promoted access to abortion in the United Kingdom and campaigned for the elimination of legal obstacles.[14] In its first year ALRA recruited 35 members, and by 1939 had almost 400 members.[14]

The ALRA was very active between 1936 and 1939 sending speakers around the country to talk about Labour and Equal Citizenship and attempted, though most often unsuccessfully, to have letters and articles published in newspapers. They became the most popular when a member of the ALRA's Medico-Legal Committee received the case of a fourteen-year-old girl who had been raped, and received a termination of this pregnancy from Dr. Joan Malleson, a progenitor of the ALRA.[14] This case gained a lot of publicity, however once the war began, the case was tucked away and the cause again lost its importance to the public.

In 1938, Joan Malleson precipitated one of the most influential cases in British abortion law when she referred a pregnant fourteen-year old rape victim to gynaecologist Aleck Bourne. He performed an abortion, then illegal, and was put on trial on charges of procuring abortion. Bourne was eventually acquitted in Rex v. Bourne as his actions were "...an example of disinterested conduct in consonance with the highest traditions of the profession".[15] This court case set a precedent that doctors could not be prosecuted for performing an abortion in cases where pregnancy would probably cause "mental and physical wreck".

The Abortion Law Reform Association continued its campaigning after the War, and this, combined with broad social changes brought the issue of abortion back into the political arena in the 1960s. President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists John Peel chaired the committee advising the British Government on what became the 1967 Abortion Act, which allowed for legal abortion on a number of grounds, including to avoid injury to the physical or mental health of the woman or her existing child(ren) if the pregnancy was still under 28 weeks.[16]

United States

In America an abortion reform movement emerged in the 1960s. In 1964 Gerri Santoro of Connecticut died trying to obtain an illegal abortion and her photo became the symbol of the pro-choice movement. Some women's rights activist groups developed their own skills to provide abortions to women who could not obtain them elsewhere. As an example, in Chicago, a group known as "Jane" operated a floating abortion clinic throughout much of the 1960s. Women seeking the procedure would call a designated number and be given instructions on how to find "Jane".[17]

In the late 1960s, a number of organizations were formed to mobilize opinion both against and for the legalization of abortion. The forerunner of the NARAL Pro-Choice America was formed in 1969 to oppose restrictions on abortion and expand access to abortion.[18] In late 1973 NARAL became the National Abortion Rights Action League.

The landmark judicial ruling of the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade ruled that a Texas statute forbidding abortion except when necessary to save the life of the mother was unconstitutional. The Court arrived at its decision by concluding that the issue of abortion and abortion rights falls under the right to privacy. The Court held that a right to privacy existed and included the right to have an abortion. The court found that a mother had a right to abortion until viability, a point to be determined by the abortion doctor. After viability a woman can obtain an abortion for health reasons, which the Court defined broadly to include psychological well-being in the decision Doe v. Bolton, delivered concurrently.

From the 1970s, and the spread of second-wave feminism, abortion and reproductive rights became unifying issues among various women's rights groups in Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, Britain, Norway, France, Germany, and Italy.[19]

In 2015, in the wake of the House of Representatives' vote to defund Planned Parenthood, Lindy West, Amelia Bonow and Kimberly Morrison launched ShoutYourAbortion to "remind supporters and critics alike abortion is a legal right to anyone who wants or needs it".[20] The women encouraged other women to share positive abortion experiences online using the hashtag #ShoutYourAbortion in order to “denounce the stigma surrounding abortion.”[21][22][23]

In 2019, the You Know Me movement started as a response to the successful 2019 passage of fetal heartbeat bills in five states in the United States, most notably the passing of anti-abortion laws in Georgia (House Bill 381)[24][25][26][27] , Ohio (House Bill 68)[28][29][30] and Alabama (House Bill 314)[31][32][33]

Around the world

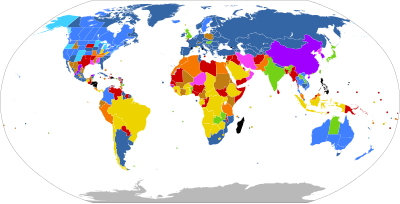

| Legal on request: | |

| No gestational limit | |

| Gestational limit after the first 17 weeks | |

| Gestational limit in the first 17 weeks | |

| Unclear gestational limit | |

| Legally restricted to cases of: | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape*, fetal impairment*, or socioeconomic factors | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life*, to her health*, or rape | |

| Risk to woman's life or to her health | |

| Risk to woman's life | |

| Illegal with no exceptions | |

| No information | |

| * Does not apply to some countries or territories in that category | |

Africa

South Africa allows abortion on demand under its Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act. Most African nations, however, have abortion bans except in cases where the woman's life or health is at risk. A number of abortion-rights international organizations have made altering abortion laws and expanding family planning services in sub-Saharan Africa and the developing world a top priority.

Asia

Japan

Chapter XXIX of the Penal Code of Japan makes abortion illegal in Japan. However, the Maternal Health Protection Law allows approved doctors to practice abortion with the consent of the mother and her spouse, if the pregnancy has resulted from rape, or if the continuation of the pregnancy may severely endanger the maternal health because of physical reasons or economic reasons. Other people, including the mother herself, trying to abort the fetus can be punished by the law. People trying to practice abortion without the consent of the woman can also be punished, including the doctors.

South Korea

Abortion has been illegal in South Korea since 1953 but on 11 April 2019, South Korea's Constitutional Court ruled the abortion ban unconstitutional and called for the law to be amended.[34] The law stands until the end of 2020. The Constitutional Court has taken into consideration abortion-rights cases by women because they find the abortion ban as unconstitutional. To help support the legalization of abortion in South Korea, thousands of advocates compiled a petition for the Blue House to consider lifting the ban. Due to the abortion ban, this has led to many dangerous self-induced abortions and other illegal practices of abortion that needs more attention. This is why there are advocates challenging the law to put into perspective the negative factors this abortion ban brings. By making abortion illegal in South Korea, this also creates an issue when it comes to women's rights and their own rights to their bodies. As a result, many women's advocate groups were created and acted together to protest against the abortion ban law.[35]

Global Day of Action is a form of protest that advocates to make a change and bring more awareness to global warming. During this protest, a group of feminist Korean advocates called, "The Joint Action for Reproductive Justice" connected with one another to promote concerns that requires more attention and needs a quick change such as making abortion legal.[36] By combining different advocate groups that serves different purposes and their own goals they want to achieve into one event, it helps promote all the different aspects of reality that needs to change.

Abortion-rights Advocate Groups:

- Center for Health and Social Change

- Femidangdang

- Femimonsters

- Flaming Feminist Action

- Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center

- Korean Women's Associations United

- Korea Women's Hot Line

- Network for Glocal Activism

- Sexual and Reproductive Rights Forum

- Womenlink

- Women with Disabilities Empathy

Europe

Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Abortion was illegal in the Republic of Ireland except when the woman's life was threatened by a medical condition (including risk of suicide), since a 1983 referendum (aka 8th Amendment) amended the constitution. Subsequent amendments in 1992 (after the X Case) – the thirteenth and fourteenth – guaranteed the right to travel abroad (for abortions) and to distribute and obtain information of "lawful services" available in other countries. Two proposal to remove suicide risk as a ground for abortion were rejected by the people, in a referendum in 1992 and in 2002. Thousands of women get around the ban by privately travelling to the other European countries (typically Britain and the Netherlands) to undergo termination,[37] or by ordering abortion pills from Women on Web online and taking them in Ireland.[38]

Sinn Féin, the Labour Party, Social Democrats, Green Party, Communist Party, Socialist Party and Irish Republican Socialist Party have made their official policies to support abortion rights. Mainstream centre-right parties such as Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael do not have official policies on abortion rights but allow conscience vote on supportive of abortion in limited circumstances.[39][40][41] Aontú, founded in January 2019, is firmly anti-abortionist and seeks to "protect the right to life."[42]

After the death of Savita Halappanavar in 2012, there has been a renewed campaign to repeal the eighth amendment and legalize abortion. As of January 2017[update], the Irish government has set up a citizens assembly to look at the issue. Their proposals, broadly supported by a cross-party Oireachtas committee, include repeal of the 8th Amendment, unrestricted access to abortion for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy and no-term limits for special cases of fatal foetal abnormalities, rape and incest.[43][44]

A referendum on the repealing of the 8th Amendment was held on 25 May 2018. Together for Yes a cross-society group formed from the Coalition to Repeal the 8th Amendment, National Women's Council of Ireland and the Abortion Rights Campaign will be the official campaign group for repeal in the referendum.[45]

Northern Ireland

Despite being part of the United Kingdom, abortion remained illegal in Northern Ireland, except in cases when the woman is threatened by a medical condition, physical or mental, until 2019.[46][47] Women seeking abortions had to travel to England. In October 2019, abortion up to 12 weeks was legalised, to begin in April 2020, but remains near-unobtainable.[48]

Poland

Poland initially held abortion to be legal in 1958 by the communist government, but was later banned after restoration of democracy in 1989.

Currently, abortion is illegal in all cases except for rape or when the fetus or mother is in fatal conditions.[49] The wide spread of Catholic Church in Poland within the country has made abortion socially 'unacceptable'[50] . The Pope has had major influence on the acceptance of abortion within Poland[51] . Several landmark court cases have had substantial influence on the current status of abortion, including Tysiac v Poland.[52][53]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the Abortion Act 1967 legalized abortion on a wide number of grounds, except in Northern Ireland. In Great Britain, the law states that pregnancy may be terminated up to 24 weeks[54] if it:

- puts the life of the pregnant woman at risk

- poses a risk to the mental and physical health of the pregnant woman

- poses a risk to the mental and physical health of the fetus

- shows there is evidence of extreme fetal abnormality i.e. the child would be seriously physically or mentally handicapped after birth and during life.[55]

However, the criterion of risk to mental and physical health is applied broadly, and de facto makes abortion available on demand,[56] though this still requires the consent of two National Health Service doctors. Abortions in Great Britain are provided at no out-of-pocket cost to the patient by the NHS.

The Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats are predominantly pro-abortion-rights parties, though with significant minorities in each either holding more restrictive definitions of the right to choose, or subscribing to an anti-abortion analysis. The Conservative Party is more evenly split between both camps and its former leader, David Cameron, supports abortion on demand in the early stages of pregnancy.[57]

Middle East

Iran

Abortion was first legalized in 1978.[58] In April 2005, the Iranian Parliament approved a new bill easing the conditions by also allowing abortion in certain cases when the fetus shows signs of handicap,[59][60] and the Council of Guardians accepted the bill in 15 June 2005.[citation needed]

Legal abortion is now allowed if the mother's life is in danger, and also in cases of fetal abnormalities that makes it not viable after birth (such as anencephaly) or produce difficulties for mother to take care of it after birth, such as major thalassemia or bilateral polycystic kidney disease.

North America

United States

Abortion-rights advocacy in the United States is centered in the United States pro-choice movement.

South America

Argentina

Because Argentina is very restrictive against abortion, reliable reporting on abortion rates is unavailable. Argentina is a strongly Catholic country, and protesters seeking liberalized abortion in 2013 directed anger toward the Catholic Church.[61] Argentina is the home of the anti-violence organization Ni una menos, which was formed in 2015 to protest the murder of Daiana García, which opposes the violation of a woman's right to choose the number and interval of pregnancies.[62][63]

See also

References

- ^ Holstein; Gubrium (2008). Handbook of Constructionist Research. Guilford Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Committed to Availability, Conflicted about Morality: What the Millennial Generation Tells Us about the Future of the Abortion Debate and the Culture Wars". Public Religion Research Institute. 9 June 2011.

- ^ Kilgore, Ed (25 May 2019). "The Big 'Pro-Life' Shift in a New Poll Is an Illusion". Intelligencer. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Goldstein, Norm, ed. The Associated Press Stylebook. Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2007.

- ^ Gordon, Sarah Barringer. "Law and Everyday Death: Infanticide and the Backlash against Woman's Rights after the Civil War." Lives of the Law. Austin Sarat, Lawrence Douglas, and Martha Umphrey, Editors. (University of Michigan Press 2006) p.67

- ^ a b Schiff, Stacy (13 October 2006). "Desperately Seeking Susan". New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Marriage and Maternity". The Revolution. Susan B. Anthony. 8 July 1869. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Susan B. Anthony, “Marriage and Maternity,” Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Revolution (8 July 1869), via University Honors Program, Syracuse University.

- ^ Federer, William. American Minute, page 81 (Amerisearch 2003).

- ^ HL Deb. Vol 72. 269.

- ^ a b c d e f Hall, Lesley (2011). The Life and Times of Stella Browne: Feminist and Free Spirit. pp. 27–178.

- ^ Jones, Greta. "Women and eugenics in Britain: The case of Mary Scharlieb, Elizabeth Sloan Chesser, and Stella Browne." Annals of Science 52 no. 5 (1995):481-502

- ^ Rowbotham, Sheila (1977). A New World for Women: Stella Browne, social feminist. pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c Hindell, Keith; Madeline Simms (1968). "How the Abortion Lobby Worked". The Political Quarterly: 271–272.

- ^ R v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687, [1938] 3 All ER 615, CCA

- ^ House of Commons, Science and Technology Committee. "Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967." 1 (2006-2007). Print.

- ^ Johnson, Linnea. "Something Real: Jane and Me. Memories and Exhortations of a Feminist Ex-Abortionist". CWLU Herstory Project. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ National Women's Health Network | A Voice For Women, A Network For Change

- ^ LeGates, Marlene. In Their Time: A History of Feminism in Western Society Routledge, 2001 ISBN 0-415-93098-7 p. 363-364

- ^ "Women Share Their Stories With #ShoutYourAbortion To Support Pro-Choice". 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020.

- ^ Klabusich, Katie (25 September 2015). "Frisky Rant: Actually, I Love Abortion". The Frisky. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Fishwick, Carmen (9 October 2015). "Why we need to talk about abortion: eight women share their experiences". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Koza, Neo (23 September 2015). "#ShoutYourAbortion activists won't be silenced". EWN Eyewitness News. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "2019-2020 Regular Session - HB 481". legis.ga.gov. Georgia General Assembly. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Fink, Jenni (18 March 2019). "GEORGIA SENATOR: ANTI-ABORTION BILL 'NATIONAL STUNT' IN RACE TO BE CONSERVATIVE STATE TO GET ROE V. WADE OVERTURNED". Newsweek. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Prabhu, Maya (29 March 2019). "Georgia's anti-abortion 'heartbeat bill' heads to governor's desk". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Mazzei, Patricia; Blinder, Alan (7 May 2019). "Georgia Governor Signs 'Fetal Heartbeat' Abortion Law". New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Kaplan, Talia (14 March 2019). "Ohio 'heartbeat' abortion ban passes Senate as governor vows to sign it". Fox News. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Frazin, Rachel (10 April 2019). "Ohio legislature sends 'heartbeat' abortion bill to governor's desk". The Hill. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ Haynes, Danielle (11 April 2019). "Ohio Gov. DeWine signs 'heartbeat' abortion bill". UPI. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ "Alabama HB314 | 2019 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Williams, Timothy; Blinder, Alan (14 May 2019). "Alabama Lawmakers Vote to Effectively Ban Abortion in the State". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Ivey, Kay (15 May 2019). "Today, I signed into law the Alabama Human Life Protection Act". Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (11 April 2019). "South Korea Rules Anti-Abortion Law Unconstitutional". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "A campaign to legalise abortion is gaining ground in South Korea". The Economist. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "South Korea: Joint Action for Reproductive Justice formed & activities for 28 September". International Campaign for Women's Right to Safe Abortion. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Irish teen wins abortion battle". BBC News. 9 May 2007.

- ^ Gartland, Fiona (27 May 2013). "Fall in seizures of drugs that induce abortion". The Irish Times.

- ^ Finn, Christina. "'I trust women': Sinn Féin says it will be 'knocking on doors' to repeal the Eighth Amendment". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Duffy, Rónán. "'Households will be split' - Leading Fianna Fáil TD doesn't back his leader on abortion". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Majority Fine Gael view on abortion referendum expected". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Bray, Jennifer (28 January 2019). "Peadar Tóibín to name new political party 'Aontú'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Final Report on the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution - The Citizens' Assembly". citizensassembly.ie. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Committee on the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution". beta.oireachtas.ie. Houses of the Oireachtas. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Who We Are - Together For Yes". Together For Yes. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Rex v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687, [1938] 3 All ER 615, CCA

- ^ "Q&A: Abortion in Northern Ireland". BBC News. 13 June 2001. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ Yeginsu, Ceylan (April 9, 2020). "Technically Legal in Northern Ireland, Abortions Are Still Unobtainable". New York Times.

- ^ Douglas, Carol Anne (1981-11-30). "Poland restricts abortion". Off Our Backs. Vol. 11, no. 10. p. 14. ProQuest 197142942.

- ^ Douglas, Carol Anne (Mar 1994). "Feminists vs. the church". Off Our Backs. Vol. 24, no. 3. p. 10. ProQuest 197123721.

- ^ https://search.proquest.com/docview/1411117675(registration required)

- ^ Hewson, Barbara (Summer 2007). "Abortion in poland: A new human rights ruling". Conscience. Vol. 28, no. 2. p. 34-35. ProQuest 195070632.

- ^ "Polish abortion law protesters march against proposed restrictions". The Guardian. Associated Press. 24 October 2016. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ "MPs reject cut in abortion limit". BBC News. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Text of the Abortion Act 1967 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk. .

- ^ R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2002] EWCA Civ 297 at [6], [2002] 2 All ER 756 at 761, CA

- ^ David Cameron supports abortion on demand, Catholic Herald, 20 June 2008.

- ^ Eliz Sanasarian, The Women's Rights Movements in Iran, Praeger, New York: 1982, ISBN 0-03-059632-7.

- ^ Harrison, Frances (12 April 2005). "Iran liberalises laws on abortion". BBC. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

- ^ "Iran's Parliament eases abortion law". The Daily Star. 13 April 2005. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

- ^ Infobae.com Society Reporting staff (26 November 2013). "In San Juan, pro-abortion militants burned an image of the Pope (En San Juan, militantes pro aborto quemaron una imagen del Papa)". infobae.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 July 2017.

Frente a la catedral, un grupo de católicos que hizo una muralla humana para evitar la profanación del templo debió soportar insultos, escupitajos y manchas de pintura.

- ^ "Maratón de lectura contra los femicidios" (in Spanish). Sur Capitalino. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "Ley de protección integral para prevenir, sancionar y erradicar la violencia contra las mujeres". niunamenos.com.ar. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.