Edward G. Robinson

Edward G. Robinson | |

|---|---|

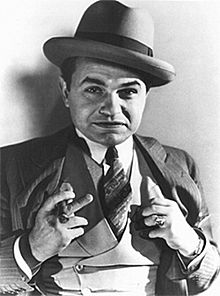

Robinson in 1948 | |

| Born | Emanuel Goldenberg December 12, 1893 |

| Died | January 26, 1973 (aged 79) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Beth El Cemetery, Brooklyn |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1913–1973 |

| Spouses | Gladys Lloyd

(m. 1927; div. 1956)Jane Robinson (m. 1958) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards | |

Edward G. Robinson (born Emanuel Goldenberg; Template:Lang-yi; December 12, 1893 – January 26, 1973) was a Romanian American actor of stage and screen during Hollywood's Golden Age. He appeared in 30 Broadway plays[1] and more than 100 films during a 50-year career[2] and is best remembered for his tough-guy roles as gangsters in such films as Little Caesar and Key Largo.

During the 1930s and 1940s, he was an outspoken public critic of fascism and Nazism, which were growing in strength in Europe leading up to World War II. His activism included contributing over $250,000 to more than 850 organizations involved in war relief, along with cultural, educational and religious groups. During the 1950s, he was called to testify at the House Un-American Activities Committee during the Red Scare, but was cleared of any deliberate Communist involvement when he claimed he was "duped" by several people whom he named (including screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, according to the official Congressional record, "Communist infiltration of Hollywood motion-picture industry").[3][4]

Robinson's roles included an insurance investigator in the film noir Double Indemnity, Dathan (adversary of Moses) in The Ten Commandments, and his final performance in the science-fiction story Soylent Green.[5] Robinson received an Academy Honorary Award for his work in the film industry, which was awarded two months after he died in 1973. He is ranked number 24 in the American Film Institute's list of the 25 greatest male stars of Classic American cinema.

Early years and education

Robinson was born as Emanuel Goldenberg to a Yiddish-speaking Romanian Jewish family in Bucharest, the son of Sarah (née Guttman) and Morris Goldenberg, a builder[dubious – discuss].[6]

After one of his brothers was attacked by an anti-semitic mob, the family decided to emigrate to the United States.[2] Robinson arrived in New York City on February 21, 1904.[7] "At Ellis Island I was born again," he wrote. "Life for me began when I was 10 years old."[2] He grew up on the Lower East Side,[8]: 91 and had his Bar Mitzvah at First Roumanian-American Congregation.[9] He attended Townsend Harris High School and then the City College of New York, planning to become a criminal attorney.[10] An interest in acting and performing in front of people led to him winning an American Academy of Dramatic Arts scholarship,[10] after which he changed his name to Edward G. Robinson (the G. standing for his original surname).[10]

He served in the United States Navy during World War I, but was never sent overseas.[11]

Career

Theatre

He began his acting career in the Yiddish Theatre District[12][13][14] in 1913, he made his Broadway debut in 1915.[2] He made his film debut in Arms and the Man (1916).

In 1923, he made his named debut as E. G. Robinson in the silent film, The Bright Shawl.[2]

The Racket

He played a snarling gangster in the 1927 Broadway police/crime drama The Racket, which led to his being cast in similar film roles, beginning with The Hole in the Wall (1929) with Claudette Colbert for Paramount.

One of many actors who saw his career flourish in the new sound film era rather than falter, he made only three films prior to 1930, but left his stage career that year and made 14 films between 1930 and 1932.

Robinson went to Universal for Night Ride (1930) and MGM for A Lady to Love (1930) directed by Victor Sjöström. At Universal he was in Outside the Law and East Is West (both 1930), then he did The Widow from Chicago (1931) at First National.

Little Caesar

Robinson was established as a film actor. What made him a star was an acclaimed performance as the gangster Caesar Enrico "Rico" Bandello in Little Caesar (1931) at Warner Bros.

Robinson signed a long term contract with Warners. They put him in another gangster film, Smart Money (1931), his only movie with James Cagney. He was reunited with Mervyn LeRoy, director of Little Caesar, in Five Star Final (1931), playing a journalist, and played a Tong gangster in The Hatchet Man (1932).

Robinson made a third film with LeRoy, Two Seconds (1932) then did a melodrama directed by Howard Hawks, Tiger Shark (1932).

Warners tried him in a biopic, Silver Dollar (1932), where Robinson played Horace Tabor, a comedy, The Little Giant (1933) and a romance, I Loved a Woman (1933).

Robinson was then in Dark Hazard (1934), and The Man with Two Faces (1934).

He went to Columbia for The Whole Town's Talking (1935), a comedy directed by John Ford. Sam Goldwyn borrowed him for Barbary Coast (1935), again directed by Hawks.

Back at Warners he did Bullets or Ballots (1936) then he went to Britain for Thunder in the City (1937). He made Kid Galahad (1937) with Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart. MGM borrowed him for The Last Gangster (1937) then he did a comedy A Slight Case of Murder (1938). Again with Bogart in a supporting role, he was in The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse (1938) then he was borrowed by Columbia for I Am the Law (1938).

World War II

At the time World War II broke out in Europe, he played an FBI agent in Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), the first American film which showed Nazism as a threat to the United States.

He volunteered for military service in June 1942 but was disqualified due to his age at 48,[15] although he became an active and vocal critic of fascism and Nazism during that period.[16]

MGM borrowed him for Blackmail, (1939). Then to avoid being typecast he played biomedical scientist and Nobel laureate Paul Ehrlich in Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet (1940) and Paul Julius Reuter in A Dispatch from Reuter's (1940).[17] Both were biographies of prominent Jewish public figures. In between, he and Bogart were in Brother Orchid (1940).[17]

Robinson was teamed with John Garfield in The Sea Wolf (1941) and George Raft in Manpower (1941). He went to MGM for Unholy Partners (1942) and made a comedy Larceny, Inc. (1942).

Post Warners

Robinson was one of several stars in Tales of Manhattan (1942) and Flesh and Fantasy (1943).

He did war films: Destroyer (1943) at Columbia, and Tampico (1944) at Fox. At Paramount he was in Billy Wilder's Double Indemnity (1944) with Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck and at Columbia he was in Mr. Winkle Goes to War (1944). He then performed with Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea in Fritz Lang's The Woman in the Window (1944) and Scarlet Street (1945) where he played a criminal painter.

At MGM he was in Our Vines Have Tender Grapes (1945), and then Orson Welles' The Stranger (1946), with Welles and Loretta Young. Robinson followed it with another thriller, The Red House (1947), and starred in an adaptation of All My Sons (1948).

Robinson appeared for director John Huston as gangster Johnny Rocco in Key Largo (1948), the last of five films he made with Humphrey Bogart and the only one in which Bogart did not play a supporting role.

He was in Night Has a Thousand Eyes in 1948 and House of Strangers in 1949.

Greylisting

Robinson found it hard to get work after his greylisting. [citation needed] He was in low budget films: Actors and Sin (1952), Vice Squad (1953), Big Leaguer (1953), The Glass Web (1953), Black Tuesday (1954), The Violent Men (1955), Tight Spot (1955), A Bullet for Joey (1955), Illegal (1955), and Hell on Frisco Bay (1955).

His career rehabilitation received a boost in 1954, when noted anti-communist director Cecil B. DeMille cast him as the traitorous Dathan in The Ten Commandments. The film was released in 1956, as was his psychological thriller Nightmare.

After a subsequent short absence from the screen, Robinson's film career—augmented by an increasing number of television roles—restarted for good in 1958/59, when he was second-billed after Frank Sinatra in the 1959 release A Hole in the Head.

Supporting Actor

Robinson went to Europe for Seven Thieves (1960). He had support roles in My Geisha (1962), Two Weeks in Another Town (1962), Sammy Going South (1963), The Prize (1963), Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), Good Neighbor Sam (1964), Cheyenne Autumn (1964), and The Outrage (1964).

He had a key part in The Cincinnati Kid (1965) and was top billed in The Blonde from Peking and Grand Slam (1967).

Robinson was originally cast in the role of Dr. Zaius in Planet Of The Apes (1968) and even went as far to filming a screen test with Charlton Heston. However, Robinson dropped out from the project before production began citing heart problems and concerns over the long hours under the heavy ape makeup. He was replaced by Maurice Evans.

Later appearances included The Biggest Bundle of Them All (1968), Never a Dull Moment (1968), It's Your Move (1968), Mackenna's Gold (1969), and the Night Gallery episode “The Messiah on Mott Street" (1971).

The last scene Robinson filmed was a euthanasia sequence, with friend and co-star Charlton Heston, in the science fiction cult film Soylent Green (1973); he died only twelve days later.

Heston, as president of the Screen Actors Guild, presented Robinson with its annual award in 1969, "in recognition of his pioneering work in organizing the union, his service during World War II, and his 'outstanding achievement in fostering the finest ideals of the acting profession.'"[8]: 124

Robinson was never nominated for an Academy Award, but in 1973 he was awarded an honorary Oscar in recognition that he had "achieved greatness as a player, a patron of the arts and a dedicated citizen ... in sum, a Renaissance man".[2] He had been notified of the honor, but died two months before the award ceremony, so the award was accepted by his widow, Jane Robinson.[2]

Radio

From 1937 to 1942, Robinson starred as Steve Wilson, editor of the Illustrated Press, in the newspaper drama Big Town.[18] He also portrayed hardboiled detective Sam Spade for a Lux Radio Theatre adaptation of The Maltese Falcon. During the 1940s he also performed on CBS Radio's "Cadena de las Américas" network broadcasts to South America in collaboration with Nelson Rockefeller's cultural diplomacy program at the U.S. State Department's Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs.[19]

Personal life

Robinson married his first wife, stage actress Gladys Lloyd, born Gladys Lloyd Cassell, in 1927; she was the former wife of Ralph L. Vestervelt and the daughter of Clement C. Cassell, an architect, sculptor and artist. The couple had one son, Edward G. Robinson, Jr. (a.k.a. Manny Robinson, 1933–1974), as well as a daughter from Gladys Robinson's first marriage.[20] In 1956 the couple divorced. In 1958 he married Jane Bodenheimer, a dress designer professionally known as Jane Arden. Thereafter he also maintained a home in Palm Springs, California.[21]

In noticeable contrast to many of his onscreen characters, Robinson was a sensitive, soft-spoken and cultured man who spoke seven languages.[2] Remaining a liberal Democrat, he attended the 1960 Democratic Convention in Los Angeles, California.[22] He was a passionate art collector, eventually building up a significant private collection. In 1956, however, he was forced to sell his collection to pay for his divorce settlement with Gladys Robinson; his finances had also suffered due to underemployment in the early 1950s.[8]: 120

Death

Robinson died at Mount Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles of bladder cancer[23] on January 26, 1973. Services were held at Temple Israel in Los Angeles where Charlton Heston delivered the eulogy.[24]: 131 Over 1,500 friends of Robinson attended with another 500 crowded outside.[8]: 125 His body was then flown to New York where it was entombed in a crypt in the family mausoleum at Beth-El Cemetery in Brooklyn.[24]: 131 Among his pallbearers were Jack L. Warner, Hal B. Wallis, Mervyn LeRoy, George Burns, Sam Jaffe, and Frank Sinatra.[2]

In October 2000, Robinson's image was imprinted on a U.S. postage stamp, its sixth in its Legends of Hollywood series.[8]: 125 [25]

Political activism

During the 1930s, Robinson was an outspoken public critic of fascism and Nazism, and donated more than $250,000 to 850 political and charitable groups between 1939 and 1949. He was host to the Committee of 56 who gathered at his home on December 9, 1938, signing a "Declaration of Democratic Independence" which called for a boycott of all German-made products.[16]

Although he tried to do so, he was unable to enlist in the military at the outbreak of World War II because of his age;[15] instead, the Office of War Information appointed him as a Special Representative based in London.[8]: 106 From there, taking advantage of his multilingual skills, he delivered radio addresses in over six languages to countries in Europe which had fallen under Nazi domination.[8]: 106 His talent as a radio speaker in the U.S. had previously been recognized by the American Legion, which had given him an award for his "outstanding contribution to Americanism through his stirring patriotic appeals."[8]: 106 Robinson was also active with the Hollywood Democratic Committee, serving on its executive board in 1944, during which time he became an "enthusiastic" campaigner for Roosevelt's reelection that year.[8]: 107 During the 1940s Robinson also contributed to the cultural diplomacy initiatives of Roosevelt's Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs in support of Pan-Americanism through his broadcasts to South America on the CBS "Cadena da las Américas" radio network.[26]

In early July 1944, less than a month after the Invasion of Normandy by Allied forces, Robinson traveled to Normandy to entertain the troops, becoming the first movie star to go there for the USO.[8]: 106 He personally donated $100,000 ($1,500,000 in 2015 dollars) to the USO.[8]: 107 After returning to the U.S. he continued his active involvement with the war effort by going to shipyards and defense plants to inspire workers, in addition to appearing at rallies to help sell war bonds.[8]: 107 After the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, while not a supporter of Communism, he appeared at Soviet war relief rallies to give moral aid to America's new ally, which he said could join "together in their hatred of Hitlerism."[8]: 107

After the war ended, Robinson spoke publicly in support of democratic rights for all Americans, especially in demanding equality for Blacks in the workplace. He endorsed the Fair Employment Practices Commission's call to end workplace discrimination.[8]: 109 Black leaders praised him as "one of the great friends of the Negro and a great advocator of Democracy."[8]: 109 Robinson also campaigned for the civil rights of African-Americans, helping out many people to overcome segregation and discrimination.[27]

During the years Robinson spoke against fascism and Nazism, although not a supporter of Communism he did not criticize the Soviet Union which he saw as an ally against Hitler. However, notes film historian Steven J. Ross, "activists who attacked Hitler without simultaneously attacking Stalin were vilified by conservative critics as either Communists, Communist dupes, or, at best, naive liberal dupes."[8]: 128 In addition, Robinson learned that 11 of the more than the 850 charities and groups he had helped over the previous decade were listed by the FBI as Communist front organizations.[28] As a result, he was called to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1950 and 1952 and was threatened with blacklisting.[29]

As appears in the full House Un-American Activities Committee transcript for April 30, 1952, Robinson "named names" of Communist sympathizers (Albert Maltz, Dalton Trumbo, John Howard Lawson, Frank Tuttle, and Sidney Buchman) and repudiated some of the organizations he had belonged to in the 1930s and 1940s.[29][30] He came to realize, "I was duped and used."[8]: 121 His own name was cleared, but in the aftermath his career noticeably suffered, as he was offered smaller roles and those less frequently. In October 1952 he wrote an article titled "How the Reds made a Sucker Out of Me", that was published in the American Legion Magazine.[31] The chair of the Committee, Francis E. Walter, told Robinson at the end of his testimonies, that the Committee "never had any evidence presented to indicate that you were anything more than a very choice sucker."[8]: 122

In popular culture

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Robinson has been the inspiration for a number of animated television characters, usually caricatures of his most distinctive 'snarling gangster' guise. An early version of the gangster character Rocky, featured in the Bugs Bunny cartoon Racketeer Rabbit, shared his likeness. This version of the character also appears briefly in Justice League, in the episode "Comfort and Joy", as an alien with Robinson's face and non-human body, who hovers past the screen as a background character.

Similar caricatures also appeared in The Coo-Coo Nut Grove, Thugs with Dirty Mugs and Hush My Mouse. Another character based on Robinson's tough-guy image was The Frog (Chauncey "Flat Face" Frog) from the cartoon series Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse. The voice of B.B. Eyes in The Dick Tracy Show was based on Robinson, with Mel Blanc and Jerry Hausner sharing voicing duties. The Wacky Races animated series character 'Clyde' from the Ant Hill Mob was based on Robinson's Little Caesar persona.

In the 1989 animated series C.O.P.S. the mastermind villain Brandon "Big Boss" Babel's voice sounded just like Edward G. Robinson when he would talk to his gangsters.[citation needed]

Voice actor Hank Azaria has noted that the voice of Simpsons character police chief Clancy Wiggum is an impression of Robinson.[32] This has been explicitly joked about in episodes of the show. In "The Day the Violence Died" (1996), a character states that Chief Wiggum is clearly based on Robinson. In 2008's "Treehouse of Horror XIX", Wiggum and Robinson's ghost each accuse the other of being rip-offs.[citation needed]

Another caricature of Robinson appears in two episodes of Star Wars: The Clone Wars season two, in the person of Lt. Tan Divo.[citation needed] Arok the Hutt was inspired by Edward G. Robinson’s gangster portrayals in Star Wars: The Clone Wars

Robinson was played by Michael Stuhlbarg in the 2015 film Trumbo. In the film he is portrayed as a weak man, going along with the House UnAmerican Committee to save his own career. In contrast, Dalton Trumbo appears to be entirely honorable when he refuses to accept money from Robinson.

Filmography

- Excluding appearances as himself.

- Arms and the Woman (1916) as Factory Worker

- The Bright Shawl (1923) as Domingo Escobar

- The Hole in the Wall (1929) as The Fox

- The Kibitzer (1930, screenplay)

- Night Ride (1930) as Tony Garotta

- A Lady to Love (1930) as Tony

- An Intimate Dinner in Celebration of Warner Brothers Silver Jubilee (1930, Short) as Himself

- Die Sehnsucht jeder Frau (1930) as Tony

- Outside the Law (1930) as Cobra Collins

- East Is West (1930) as Charlie Yong

- The Widow from Chicago (1930) as Dominic

- How I Play Golf by Bobby Jones No. 10: Trouble Shots (1931, Short) as Himself (uncredited)

- Little Caesar (1931) (with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.) as Little Caesar – Alias 'Rico'

- The Stolen Jools (1931, Short) (with Wallace Beery) as Gangster

- Smart Money (1931) (with James Cagney) as Nick Venizelos

- Five Star Final (1931) as Randall

- The Hatchet Man (1932) as Wong Low Get

- Two Seconds (1932) as John Allen

- Tiger Shark (1932) as Mike Mascarenhas

- Silver Dollar (1932) as Yates Martin

- The Little Giant (1933) as Bugs Ahearn

- I Loved a Woman (1933) as John Mansfield Hayden

- Dark Hazard (1934) as Jim 'Buck' Turner

- The Man with Two Faces (1934) as Damon Welles / Jules Chautard

- The Whole Town's Talking (1935) as Arthur Ferguson Jones

- Barbary Coast (1935) as Luis Chamalis

- Bullets or Ballots (1936) (with Humphrey Bogart) as Detective Johnny Blake

- Thunder in the City (1937) as Dan Armstrong

- A Day at Santa Anita (1937, Short) as Himself (uncredited)

- Kid Galahad (1937) (with Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart) as Nick Donati

- The Last Gangster (1937) (with James Stewart) as Joe Krozac

- A Slight Case of Murder (1938) as Remy Marco

- The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse (1938) (with Claire Trevor and Humphrey Bogart) as Dr. Clitterhouse

- I Am the Law (1938) as Prof. John Lindsay

- Verdensberømtheder i København (1939, Documentary) as Himself

- Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) as Edward Renard

- Blackmail (1939) as John R. Ingram

- Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet (1940) as Dr. Paul Ehrlich

- Brother Orchid (1940) (with Humphrey Bogart) as 'Little' John T. Sarto

- A Dispatch from Reuter's (1940) as Julius Reuter

- The Sea Wolf (1941) (with John Garfield) as 'Wolf' Larsen

- Manpower (1941) (with Marlene Dietrich and George Raft) as Hank McHenry

- Polo with the Stars (1941, Short) as Himself – Watching Polo Match (uncredited)

- Unholy Partners (1941) as Bruce Corey

- Larceny, Inc. (1942) as Pressure' Maxwell

- Tales of Manhattan (1942) as Avery L. 'Larry' Browne

- Moscow Strikes Back (1942, Documentary) as Narrator

- Magic Bullets (1943, Short Documentary) as Narrator

- Flesh and Fantasy (1943) as Marshall Tyler (Episode 2)

- Destroyer (1943) as Steve Boleslavski

- Tampico (1944) as Captain Bart Manson

- Double Indemnity (1944) (with Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck) as Barton Keyes

- Mr. Winkle Goes to War (1944) as Wilbert Winkle

- The Woman in the Window (1944) as Professor Richard Wanley

- Our Vines Have Tender Grapes (1945) as Martinius Jacobson

- Journey Together (1945) as Dean McWilliams

- Scarlet Street (1945) as Christopher Cross

- American Creed (1946, Short) as Himself

- The Stranger (1946) (with Loretta Young and Orson Welles) as Mr. Wilson

- The Red House (1947) as Pete Morgan

- All My Sons (1948) (with Burt Lancaster) as Joe Keller

- Key Largo (1948) (with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall) as Johnny Rocco

- Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) as John Triton

- House of Strangers (1949) as Gino Monetti

- It's a Great Feeling (1949) as Himself (uncredited)

- Operation X (1950) as George Constantin

- Actors and Sin (1952) as Maurice Tillayou (segment "Actor's Blood")

- Vice Squad (1953) as Capt. 'Barnie' Barnaby

- Big Leaguer (1953) as John B. 'Hans' Lobert

- The Glass Web (1953) as Henry Hayes

- Black Tuesday (1954) as Vincent Canelli

- For the Defense (1954 TV movie) as Matthew Considine

- The Violent Men (1955) as Lew Wilkison

- Tight Spot (1955) as Lloyd Hallett

- A Bullet for Joey (1955) as Inspector Raoul Leduc

- Illegal (1955) as Victor Scott

- Hell on Frisco Bay (1955) as Victor Amato

- Nightmare (1956) as Rene Bressard

- The Ten Commandments (1956) as Dathan

- The Heart of Show Business (1957, Short) as Narrator

- A Hole in the Head (1959) (with Frank Sinatra) as Mario Manetta

- Seven Thieves (1960) as Theo Wilkins

- The Right Man (1960, TV Movie) as Theodore Roosevelt

- Pepe (1960) (with Cantinflas) as Himself

- My Geisha (1962) as Sam Lewis

- Two Weeks in Another Town (1962) (with Kirk Douglas) as Maurice Kruger

- Sammy Going South (1963) (a.k.a. A Boy Ten Feet Tall) as Cocky Wainwright

- The Prize (1963) as Dr. Max Stratman

- Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964) (with the Rat Pack) as Big Jim Stevens (uncredited)

- Good Neighbor Sam (1964) (with Jack Lemmon) as Simon Nurdlinger

- Cheyenne Autumn (1964) as Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz

- The Outrage (1964) as Con Man

- Who Has Seen the Wind? (1965, TV Movie) as Captain

- The Cincinnati Kid (1965) (with Steve McQueen) as Lancey Howard

- All About People (1967, Short) as Narrator

- The Blonde from Peking (1967) as Douglas – chef C.I.A.

- Grand Slam (1967) as Prof. James Anders

- Operation St. Peter's (1967) as Joe Ventura

- The Biggest Bundle of Them All (1968) as Professor Samuels

- Never a Dull Moment (1968) (with Dick Van Dyke) as Leo Joseph Smooth

- It's Your Move (1968) as Sir George McDowell

- Mackenna's Gold (1969) (with Gregory Peck) as Old Adams

- U.M.C., aka Operation Heartbeat (1969, TV Movie; pilot for Medical Center) as Dr. Lee Forestman

- The Old Man Who Cried Wolf (1970, TV Movie) as Emile Pulska

- Song of Norway (1970) as Krogstad

- Mooch Goes to Hollywood (1971) as Himself – Party guest (uncredited)

- Night Gallery (1971) Season 2, episode 13a (The Messiah on Mott Street) as Abe Goldman

- Neither by Day Nor by Night (1972) as Father

- Soylent Green (1973) (with Charlton Heston) as Sol Roth (final film role)

Radio appearances

| Year | Program | Episode/source |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Screen Guild Theatre | Blind Alley[33] |

| 1946 | Suspense | The Man Who Wanted to Be Edward G. Robinson[34] |

| 1946 | This Is Hollywood | The Stranger[35] |

| 1950 | Screen Directors Playhouse | The Sea Wolf[35] |

See also

References

- ^ "Edward G. Robinson – Broadway Cast & Staff | IBDB". www.ibdb.com. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Edward G. Robinson, 79, Dies; His 'Little Caesar' Set a Style; Man of Great Kindness Edward G. Robinson Is Dead at 79 Made Speeches to Friends Appeared in 100 Films". The New York Times. January 27, 1973. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/communistinfiltr07unit#page/2421/mode/1up

- ^ http://todayinclh.com/?event=actor-edward-g-robinson-confesses-to-huac-i-was-a-sucker

- ^ Obituary Variety, January 31, 1973, p. 71.

- ^ Parish, James Robert; Marill, Alvin (1972). The Cinema of Edward G. Robinson. South Brunswick, New Jersey: A. S. Barnes. p. 16. ISBN 0-498-07875-2.

- ^ 1904 passenger list for Manole Goldenberg. "Ancestry.com".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Ross, Steven (2011). Hollywood Left and Right. How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518172-2. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Epstein (2007), p. 249

- ^ a b c Pendergast, Tom. Ed. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, Vol. 4, pp. 229–230

- ^ Beck, Robert. Edward G. Robinson Encyclopedia. McFarland. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ Morgen Stevens-Garmon (February 7, 2012). "Treasures and "Shandas" from the Collection on Yiddish theater". Museum of the City of New York. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Hy Brett (1997). The Ultimate New York City Trivia Book. Thomas Nelson Inc. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Cary Leiter (2008). The Importance of the Yiddish Theatre in the Evolution of the Modern American Theatre. ProQuest. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Wise, James: Stars in Khaki: Movie Actors in the Army and Air Services. Naval Institute Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55750-958-1. p. 228.

- ^ a b Ross, pp. 99–102

- ^ a b Schatz, Thomas. Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s. University of California Press, Nov 23, 1999, p. 99.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 88-89. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

Big Town, crime drama.

- ^ Dissonant Divas in Chicana Music: The Limits of La Onda Deborah R. Vargas. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2012 p. 152-153 ISBN 978-0-8166-7316-2 Edward G. Robbinson, OCIAA, CBS radio, Pan-americanism and Cadena de las Americas on google.books.com

- ^ "Edward G. Robinson, Jr. Is Dead; Late Screen Star's Son Was 40". The New York Times. February 27, 1974. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

Edward G. Robinson Jr., the son of the late screen actor, died yesterday. Mr. Robinson, who was 40 years old, was found unconscious by his wife, Nan, in their West Hollywood home. His death was attributed to natural causes.

- ^ Meeks, Eric G. (2012). The Best Guide Ever to Palm Springs Celebrity Homes. Horatio Limburger Oglethorpe. p. 91. ISBN 978-1479328598.

- ^ soapbxprod (November 20, 2011). "1960 Democratic Convention Los Angeles Committee for the Arts". Retrieved April 2, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Gansberg, p. 246, 252–253.

- ^ a b Beck, Robert. The Edward G. Robinson Encyclopedia, McFarland (2002)

- ^ Edward G. Robinson stamp, 2000

- ^ Dissonant Divas in Chicana Music: The Limits of La Onda Deborah R. Vargas. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2012 p. 152-153 ISBN 978-0-8166-7316-2 Edward G. Robbinson, OCIAA, CBS radio, Pan-americanism and Cadena de las Americas on google.books.com

- ^ Lotchin, Roger W. (2000). The Way We Really Were: The Golden State in the Second Great War. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252068195.

- ^ Miller, Frank. Leading Men, Chronicle Books and TCM (2006) p. 185

- ^ a b Sabin, Arthur J. In Calmer Times: The Supreme Court and Red Monday, p. 35. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999

- ^ Bud and Ruth Schultz, It Did Happen Here: Recollections of Political Repression in America, p. 113. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- ^ Ross, Stephen J. "Little Caesar and the McCarthyist Mob", USC Trojan Magazine. Los Angeles: University of Southern California, August 2011 issue. Accessed on Jan 10, 2013. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Joe Rhodes (October 21, 2000). "Flash! 24 Simpsons Stars Reveal Themselves". TV Guide.

- ^ "Sunday Caller". Harrisburg Telegraph. February 24, 1940. p. 17. Retrieved July 20, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Man Who Wanted to Be Edward G. Robinson". Harrisburg Telegraph. October 12, 1946. p. 17. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Those Were the Days". Nostalgia Digest. 42 (3): 39. Summer 2016.

Further reading

- Gansberg, Alan L. (2004). Little Caesar: A Biography of Edward G. Robinson. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4950-1.

- Epstein, Lawrence Jeffrey (2007). Edge of a Dream: The Story of Jewish Immigrants on New York's Lower East Side, 1880–1920. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7879-8622-3.

- Robinson, Edward G.; Spigelgass, Leonard (1973). All My Yesterdays; an Autobiography. Hawthorn Books. LCCN 73005443.

External links

- 1893 births

- 1973 deaths

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actor winners

- Male actors from Palm Springs, California

- American Academy of Dramatic Arts alumni

- American Jews

- Jewish American art collectors

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American male silent film actors

- Broadway actors

- American people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- California Democrats

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Jewish activists

- Jewish American male actors

- Townsend Harris High School alumni

- City College of New York alumni

- Hollywood blacklist

- Male actors from New York City

- New York (state) Democrats

- Male actors from Bucharest

- People from the Lower East Side

- Romanian emigrants to the United States

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Deaths from bladder cancer

- Burials in New York (state)

- Romanian Jews

- Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award

- Yiddish theatre performers

- 20th-century American male actors

- Warner Bros. contract players

- American people of Jewish descent