Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP (Grand Old Party), is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with its main, historic rival, the Democratic Party.

The GOP was founded in 1854 by opponents of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed for the potential expansion of slavery into the western territories. The party supported classical liberalism, opposed the expansion of slavery, and supported economic reform.[14][15] Abraham Lincoln was the first Republican president. Under the leadership of Lincoln and a Republican Congress, slavery was banned in the United States in 1865. The Party was generally dominant during the Third Party System and the Fourth Party System. After 1912, the Party underwent a social ideological shift to the right.[16] Following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the party's core base shifted, with Southern states becoming more reliably Republican in presidential politics.[17] The party's 21st-century base of support includes people living in rural areas, men, the Silent Generation, white Americans, and evangelical Christians.[18][19][20][21]

The 21st-century Republican Party ideology is American conservatism, which incorporates both economic policies and social values. The GOP supports lower taxes, free market capitalism, restrictions on immigration, increased military spending, gun rights, restrictions on abortion, deregulation and restrictions on labor unions.[22] After the Supreme Court's 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, the Republican Party opposed abortion in its party platform and grew its support among evangelicals.[23] The GOP was strongly committed to protectionism and tariffs at its founding but grew more supportive of free trade in the 20th century.

There have been 19 Republican presidents (including incumbent president Donald Trump, who was elected in 2016), the most from any one political party. As of 2020, the GOP controls the presidency, a majority in the U.S. Senate, a majority of state governorships, a majority (29) of state legislatures, and 21 state government trifectas (governorship and both legislative chambers). Five of the eight sitting U.S. Supreme Court justices were nominated by Republican presidents, with a sixth (Amy Coney Barrett) awaiting Senate confirmation to fill the vacant ninth spot.

History

19th century

The Republican Party emerged from the great political realignment of the mid-1850s. William Gienapp argues that the great realignment of the 1850s began before the Whig party collapse, and was caused not by politicians but by voters at the local level. The central forces were ethno-cultural, involving tensions between pietistic Protestants versus liturgical Catholics, Lutherans and Episcopalians regarding Catholicism, prohibition, and nativism. Anti-slavery did play a role but it was less important at first. The Know-Nothing party embodied the social forces at work, but its weak leadership was unable to solidify its organization, and the Republicans picked it apart. Nativism was so powerful that the Republicans could not avoid it, but they did minimize it and turn voter wrath against the threat that slave owners would buy up the good farm lands wherever slavery was allowed. The realignment was a powerful because it forced voters to switch parties, as typified by the rise and fall of the Know-Nothings, the rise of the Republican Party, and the splits in the Democratic Party.[24][25]

The Republican Party was founded in the Northern states in 1854 by forces opposed to the expansion of slavery, ex-Whigs, and ex-Free Soilers. The Republican Party quickly became the principal opposition to the dominant Democratic Party and the briefly popular Know Nothing Party. The party grew out of opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory to slavery and future admission as slave states.[26][27] The Republicans called for economic and social modernization. They denounced the expansion of slavery as a great evil, but did not call for ending it in the Southern states. The first public meeting of the general anti-Nebraska movement, at which the name Republican was proposed, was held on March 20, 1854 at the Little White Schoolhouse in Ripon, Wisconsin.[28] The name was partly chosen to pay homage to Thomas Jefferson's Republican Party.[29] The first official party convention was held on July 6, 1854 in Jackson, Michigan.[30]

At the 1856 Republican National Convention, the party adopted a national platform emphasizing opposition to the expansion of slavery into U.S. territories.[31] While Republican candidate John C. Frémont lost the 1856 United States presidential election to James Buchanan, he did win 11 of the 16 northern states.[32]

The Republican Party first came to power in the elections of 1860 when it won control of both houses of Congress and its candidate, former congressman Abraham Lincoln, was elected president. In the election of 1864, it united with War Democrats to nominate Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket;[32] Lincoln won re-election.[33] Under Republican congressional leadership, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution—which banned slavery in the United States—passed the Senate in 1864 and the House in 1865; it was ratified in December 1865.[34]

The party's success created factionalism within the party in the 1870s. Those who believed that Reconstruction had been accomplished, and was continued mostly to promote the large-scale corruption tolerated by President Ulysses S. Grant, ran Horace Greeley for the presidency in 1872 on the Liberal Republican Party line. The Stalwart faction defended Grant and the spoils system, whereas the Half-Breeds pushed for reform of the civil service.[35] The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act was passed in 1883;[36] the bill was signed into law by Republican President Chester A. Arthur.[37]

The Republican Party supported hard money (i.e. the gold standard), high tariffs to promote economic growth, high wages and high profits, generous pensions for Union veterans, and (after 1893) the annexation of Hawaii. The Republicans had strong support from pietistic Protestants, but they resisted demands for Prohibition. As the Northern postwar economy boomed with heavy and light industry, railroads, mines, fast-growing cities, and prosperous agriculture, the Republicans took credit and promoted policies to sustain the fast growth.[citation needed]

The GOP was usually dominant over the Democrats during the Third Party System (1850s–1890s). However, by 1890 the Republicans had agreed to the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Interstate Commerce Commission in response to complaints from owners of small businesses and farmers. The high McKinley Tariff of 1890 hurt the party and the Democrats swept to a landslide in the off-year elections, even defeating McKinley himself. The Democrats elected Grover Cleveland in 1884 and 1892. The election of William McKinley in 1896 was marked by a resurgence of Republican dominance that lasted (except for 1912 and 1916) until 1932. McKinley promised that high tariffs would end the severe hardship caused by the Panic of 1893 and that Republicans would guarantee a sort of pluralism in which all groups would benefit.[38]

The Republican Civil War era program included free homestead farms, a federally subsidized transcontinental railroad, a national banking system, a large national debt, land grants for higher education, a new national banking system, a wartime income tax and permanent high tariffs to promote industrial growth and high wages. By the 1870s, they had adopted as well a hard money system based on the gold standard and fought off efforts to promote inflation through Free Silver.[39] They created the foundations of the modern welfare state through an extensive program of pensions for Union veterans.[40] Foreign-policy issues were rarely a matter of partisan dispute, but briefly in the 1893–1904 period the GOP supported imperialistic expansion regarding Hawaii, the Philippines and the Panama Canal.[41]

20th century

The 1896 realignment cemented the Republicans as the party of big businesses while Theodore Roosevelt added more small business support by his embrace of trust busting. He handpicked his successor William Howard Taft in 1908, but they became enemies as the party split down the middle. Taft defeated Roosevelt for the 1912 nomination and Roosevelt ran on the ticket of his new Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party. He called for social reforms, many of which were later championed by New Deal Democrats in the 1930s. He lost and when most of his supporters returned to the GOP they found they did not agree with the new conservative economic thinking, leading to an ideological shift to the right in the Republican Party.[42] The Republicans returned to the White House throughout the 1920s, running on platforms of normalcy, business-oriented efficiency and high tariffs. The national party platform avoided mention of prohibition, instead of issuing a vague commitment to law and order.[43]

Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover were resoundingly elected in 1920, 1924 and 1928, respectively. The Teapot Dome scandal threatened to hurt the party, but Harding died and the opposition splintered in 1924. The pro-business policies of the decade seemed to produce an unprecedented prosperity until the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression.[44]

New Deal era

The New Deal coalition of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt controlled American politics for most of the next three decades, excluding the two-term presidency of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower. After Roosevelt took office in 1933, New Deal legislation sailed through Congress and the economy moved sharply upward from its nadir in early 1933. However, long-term unemployment remained a drag until 1940. In the 1934 midterm elections, 10 Republican senators went down to defeat, leaving the GOP with only 25 senators against 71 Democrats. The House of Representatives likewise had overwhelming Democratic majorities.[45]

The Republican Party factionalized into a majority "Old Right" (based in the Midwest) and a liberal wing based in the Northeast that supported much of the New Deal. The Old Right sharply attacked the "Second New Deal" and said it represented class warfare and socialism. Roosevelt was re-elected in a landslide in 1936; however, as his second term began, the economy declined, strikes soared, and he failed to take control of the Supreme Court or to purge the Southern conservatives from the Democratic Party. Republicans made a major comeback in the 1938 elections and had new rising stars such as Robert A. Taft of Ohio on the right and Thomas E. Dewey of New York on the left.[46] Southern conservatives joined with most Republicans to form the conservative coalition, which dominated domestic issues in Congress until 1964. Both parties split on foreign policy issues, with the anti-war isolationists dominant in the Republican Party and the interventionists who wanted to stop Adolf Hitler dominant in the Democratic Party. Roosevelt won a third and fourth term in 1940 and 1944, respectively. Conservatives abolished most of the New Deal during the war, but they did not attempt to reverse Social Security or the agencies that regulated business.[47]

Historian George H. Nash argues:

Unlike the "moderate", internationalist, largely eastern bloc of Republicans who accepted (or at least acquiesced in) some of the "Roosevelt Revolution" and the essential premises of President Truman's foreign policy, the Republican Right at heart was counterrevolutionary. Anti-collectivist, anti-Communist, anti-New Deal, passionately committed to limited government, free market economics, and congressional (as opposed to executive) prerogatives, the G.O.P. conservatives were obliged from the start to wage a constant two-front war: against liberal Democrats from without and "me-too" Republicans from within.[48]

After 1945, the internationalist wing of the GOP cooperated with Harry S. Truman's Cold War foreign policy, funded the Marshall Plan and supported NATO, despite the continued isolationism of the Old Right.[49]

The second half of the 20th century saw the election or succession of Republican presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. Eisenhower had defeated conservative leader Senator Robert A. Taft for the 1952 nomination, but conservatives dominated the domestic policies of the Eisenhower administration. Voters liked Eisenhower much more than they liked the GOP and he proved unable to shift the party to a more moderate position. Since 1976, liberalism has virtually faded out of the Republican Party, apart from a few Northeastern holdouts.[50]

The presidency of Reagan, lasting from 1981 to 1989, constituted what is known as the "Reagan Revolution".[51] It was seen as a fundamental shift from the stagflation of the 1970s before it, with the introduction of Reaganomics intended to cut taxes, prioritize government deregulation, and shift funding from the domestic sphere into the military to combat the Soviet Union by utilizing deterrence theory. A defining moment in Reagan's term of office was his speech in then-West Berlin where he demanded Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev to "[t]ear down this wall", referring to the Berlin Wall constructed to separate West and East Berlin.[52][53]

Since he left office in 1989, Reagan has been an iconic conservative Republican and Republican presidential candidates frequently claim to share his views and aim to establish themselves and their policies as the more appropriate heir to his legacy.[54]

In the Republican Revolution of 1994, the party—led by House Minority Whip Newt Gingrich, who campaigned on the "Contract with America"—won majorities in both Houses of Congress. However, as House Speaker, Gingrich was unable to deliver on many of its promises, including a balanced-budget amendment and term limits for members of Congress. During the impeachment and acquittal of President Bill Clinton, Republicans suffered surprise losses in the 1998 midterm elections. Gingrich's popularity sank to 17%; he resigned the speakership and later resigned from Congress altogether.[55][56][57]

For most of the post-World War II era, Republicans had little presence at the state legislative level. This trend began to reverse in the late 1990s, with Republicans increasing their state legislative presence and taking control of state legislatures in the South. From 2004 to 2014, the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC) raised over $140 million targeted to state legislature races, while the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLSC) raised less than half that during that time period. Following the 2014 midterm elections, Republicans controlled 68 of 98 partisan state legislative houses (the most in the party's history) and controlled both the executive and legislative branches of government in 24 states (Democrats had control of only seven).[58]

21st century

A Republican ticket of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney won the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections.[59] With the inauguration of Bush as president, the Republican Party remained fairly cohesive for much of the 2000s as both strong economic libertarians and social conservatives opposed the Democrats, whom they saw as the party of bloated, secular, and liberal government.[60] The Bush-era rise of what were known as "pro-government conservatives"—a core part of the President's base—meant that a considerable group of the Republicans advocated for increased government spending and greater regulations covering both the economy and people's personal lives as well as for an activist, interventionist foreign policy.[citation needed] Survey groups such as the Pew Research Center found that social conservatives and free market advocates remained the other two main groups within the party's coalition of support, with all three being roughly equal in number.[61][62] However, libertarians and libertarian-leaning conservatives increasingly found fault with what they saw as Republicans' restricting of vital civil liberties while corporate welfare and the national debt hiked considerably under Bush's tenure.[63] In contrast, some social conservatives expressed dissatisfaction with the party's support for economic policies that conflicted with their moral values.[64]

Bush campaigned as a "compassionate conservative" in 2000, wanting to better appeal to immigrants and minority voters.[65] The goal was to prioritize drug rehabilitation programs and aide for prisoner reentry into society, a move intended to capitalize on President Clinton's tougher crime initiatives such as the 1994 crime bill passed under his administration. The platform failed to gain much traction among members of the party during his presidency.[66]

The Republican Party lost its Senate majority in 2001 when the Senate became split evenly; nevertheless, the Republicans maintained control of the Senate due to the tie-breaking vote of Republican Vice President Dick Cheney. Democrats gained control of the Senate on June 6, 2001, when Republican Sen. Jim Jeffords switched his party affiliation to Democrat. The Republicans regained the Senate majority in the 2002 elections. Republican majorities in the House and Senate were held until the Democrats regained control in the mid-term elections of 2006.[67][68]

In the presidential election of 2008, the John McCain-Sarah Palin ticket was defeated by Senators Barack Obama and Joe Biden.[69]

The Republicans experienced electoral success in the wave election of 2010, which coincided with the ascendancy of the Tea Party movement.[70][71][72][73] (The Tea Party movement is an American fiscally conservative political movement. Members of the movement called for lower taxes, and for a reduction of the national debt of the United States and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.[74][75] The Tea Party movement has been described as a popular constitutional movement[76] composed of a mixture of libertarian, right-wing populist, and conservative activism.) That success began with the upset win of Scott Brown in the Massachusetts special Senate election for a seat that had been held for decades by the Democratic Kennedy brothers.[77] In the November elections, Republicans recaptured control of the House, increased their number of seats in the Senate and gained a majority of governorships.[78]

Obama and Biden won re-election in 2012, defeating a Mitt Romney-Paul Ryan ticket.[79] The campaign focused largely on the Affordable Care Act and President Obama's stewardship of the economy, as the country still faced high unemployment numbers and a rising national debt stemming from the Great Recession.[citation needed] While Republicans lost seven seats in the House in the November congressional elections, they still retained control of that chamber.[80] However, Republicans were not able to gain control of the Senate, continuing their minority status with a net loss of two seats.[81] In the aftermath of the loss, some prominent Republicans spoke out against their own party.[82][83][84] A post-2012 post-mortem report by the Republican Party concluded that the party needed to do more on the national level to attract votes from minorities and young voters.[85] In March 2013, National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus gave a stinging report on the party's electoral failures in 2012, calling on Republicans to reinvent themselves and officially endorse immigration reform. He said: "There's no one reason we lost. Our message was weak; our ground game was insufficient; we weren't inclusive; we were behind in both data and digital, and our primary and debate process needed improvement". He proposed 219 reforms that included a $10 million marketing campaign to reach women, minorities and gays as well as setting a shorter, more controlled primary season and creating better data collection facilities.[86]

A March 2013 poll found that a majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents under the age of 49 supported legal recognition of same-sex marriages. Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich remarked that the "[p]arty is going to be torn on this issue".[87][88] A Reuters/Ipsos survey from April 2015 found that 68% of Americans overall would attend the same-sex wedding of a loved one, with 56% of Republicans agreeing. Reuters journalist Jeff Mason remarked that "Republicans who stake out strong opposition to gay marriage could be on shaky political ground if their ultimate goal is to win the White House" given the divide between the social conservative stalwarts and the rest of the United States that opposes them.[89] In 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled bans on same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional, thus legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide.[90] In 2016, after being elected president, Republican Donald Trump stated that he was "fine" with same-sex marriage.[91]

Following the 2014 midterm elections, the Republican Party took control of the Senate by gaining nine seats.[92] With a final total of 247 seats (57%) in the House and 54 seats in the Senate, the Republicans ultimately achieved their largest majority in the Congress since the 71st Congress in 1929.[93]

The election of Republican Donald J. Trump to the presidency in 2016 marked a populist shift in the Republican Party.[94] Trump's defeat of Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton was unexpected, as polls had shown Clinton leading the race.[95] Trump's victory was fueled by narrow victories in three states—Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—that traditionally vote for Democratic presidential candidates. According to NBC News, "Trump’s power famously came from his 'silent majority' — working-class white voters who felt mocked and ignored by an establishment loosely defined by special interests in Washington, news outlets in New York and tastemakers in Hollywood. He built trust within that base by abandoning Republican establishment orthodoxy on issues like trade and government spending in favor of a broader nationalist message".[96]

After the 2016 elections, Republicans maintained a majority in the Senate, House, Governorships and elected Donald Trump as President. The Republican Party controlled 69 of 99 state legislative chambers in 2017, the most it had held in history;[97] and at least 33 governorships, the most it had held since 1922.[98] The party had total control of government (legislative chambers and governorship) in 25 states,[99][100] the most since 1952;[101] the opposing Democratic Party had full control in only five states.[102]

As of 2020, there have been a total of 19 Republican Presidents (the most from any one party in American history). Republicans have won 24 of the last 40 presidential elections.[103] Following the results of the 2018 midterm elections, the Republican Party controls the bulk of the power in the United States as of 2020, holding the Executive Branch (Donald Trump), a majority in the United States Senate, and a majority of governorships (27) and state legislatures (full control of 30/50 legislatures, split control of two).[104] As of 2019, the GOP holds a "trifecta" (control of the executive branch and both chambers of the legislative branch) in a plurality of states (22 of 50).[105] Five of the eight current justices of the Supreme Court were appointed by Republican presidents.[106]

Trump has announced that he is seeking re-election in 2020. He has confirmed that Vice President Mike Pence will once again be his running mate.[107] The slogans for the 2020 race were decided as "Keep America Great" and "Promises Made, Promises Kept".[108][109]

Donald Trump was impeached on December 18, 2019, on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.[110][111] He was acquitted by the United States Senate on February 5, 2020.[112] 195 of the 197 Republicans within the House voted against the charges with none voting in favor, the two abstaining Republicans were due to external reasons unrelated to the impeachment itself.[113] 52 of the 53 Republicans within the Senate voted against the charges as well, successfully exonerating Trump as a result, with only Senator Mitt Romney of Utah dissenting and voting in favor of the charges.[114][115]

Name and symbols

The party's founding members chose the name Republican Party in the mid-1850s as homage to the values of republicanism promoted by Thomas Jefferson's Republican Party.[117] The idea for the name came from an editorial by the party's leading publicist, Horace Greeley, who called for "some simple name like 'Republican' [that] would more fitly designate those who had united to restore the Union to its true mission of champion and promulgator of Liberty rather than propagandist of slavery".[118] The name reflects the 1776 republican values of civic virtue and opposition to aristocracy and corruption.[119] It is important to note that "republican" has a variety of meanings around the world and the Republican Party has evolved such that the meanings no longer always align.[120][121]

The term "Grand Old Party" is a traditional nickname for the Republican Party and the abbreviation "GOP" is a commonly used designation. The term originated in 1875 in the Congressional Record, referring to the party associated with the successful military defense of the Union as "this gallant old party". The following year in an article in the Cincinnati Commercial, the term was modified to "grand old party". The first use of the abbreviation is dated 1884.[122]

The traditional mascot of the party is the elephant. A political cartoon by Thomas Nast, published in Harper's Weekly on November 7, 1874, is considered the first important use of the symbol.[123] An alternate symbol of the Republican Party in states such as Indiana, New York and Ohio is the bald eagle as opposed to the Democratic rooster or the Democratic five-pointed star.[124][125] In Kentucky, the log cabin is a symbol of the Republican Party (not related to the gay Log Cabin Republicans organization).[126]

Traditionally the party had no consistent color identity.[127][128][129] After the 2000 election, the color red became associated with Republicans. During and after the election, the major broadcast networks used the same color scheme for the electoral map: states won by Republican nominee George W. Bush were colored red and states won by Democratic nominee Al Gore were colored blue. Due to the weeks-long dispute over the election results, these color associations became firmly ingrained, persisting in subsequent years. Although the assignment of colors to political parties is unofficial and informal, the media has come to represent the respective political parties using these colors. The party and its candidates have also come to embrace the color red.[130]

Political positions

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Economic policies

Republicans believe that free markets and individual achievement are the primary factors behind economic prosperity. Republicans frequently advocate in favor of fiscal conservatism during Democratic administrations; however, they have shown themselves willing to increase federal debt when they are in charge of the government (the implementation of the Bush tax cuts, Medicare Part D and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 are examples of this willingness).[131][132][133] Despite pledges to roll back government spending, Republican administrations have, since the late 1960s, sustained or increased previous levels of government spending.[134][135]

Modern Republicans advocate the theory of supply side economics, which holds that lower tax rates increase economic growth.[136] Many Republicans oppose higher tax rates for higher earners, which they believe are unfairly targeted at those who create jobs and wealth. They believe private spending is more efficient than government spending. Republican lawmakers have also sought to limit funding for tax enforcement and tax collection.[137]

Republicans believe individuals should take responsibility for their own circumstances. They also believe the private sector is more effective in helping the poor through charity than the government is through welfare programs and that social assistance programs often cause government dependency.[citation needed]

Republicans believe corporations should be able to establish their own employment practices, including benefits and wages, with the free market deciding the price of work. Since the 1920s, Republicans have generally been opposed by labor union organizations and members. At the national level, Republicans supported the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which gives workers the right not to participate in unions. Modern Republicans at the state level generally support various right-to-work laws, which prohibit union security agreements requiring all workers in a unionized workplace to pay dues or a fair-share fee, regardless of if they are members of the union or not.[138]

Most Republicans oppose increases in the minimum wage, believing that such increases hurt businesses by forcing them to cut and outsource jobs while passing on costs to consumers.[139]

The party opposes a single-payer health care system, describing it as socialized medicine. The Republican Party has a mixed record of supporting the historically popular Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid programs.[140]

Environmental policies

Historically, progressive leaders in the Republican Party supported environmental protection. Republican President Theodore Roosevelt was a prominent conservationist whose policies eventually led to the creation of the National Park Service.[141] While Republican President Richard Nixon was not an environmentalist, he signed legislation to create the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and had a comprehensive environmental program.[142] However, this position has changed since the 1980s and the administration of President Ronald Reagan, who labeled environmental regulations a burden on the economy.[143] Since then, Republicans have increasingly taken positions against environmental regulation, with some Republicans rejecting the scientific consensus on climate change.[143][144][145][146]

In 2006, then-California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger broke from Republican orthodoxy to sign several bills imposing caps on carbon emissions in California. Then-President George W. Bush opposed mandatory caps at a national level. Bush's decision not to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant was challenged in the Supreme Court by 12 states,[147] with the court ruling against the Bush administration in 2007.[148] Bush also publicly opposed ratification of the Kyoto Protocols[143][149] which sought to limit greenhouse gas emissions and thereby combat climate change; his position was heavily criticized by climate scientists.[150]

The Republican Party rejects cap-and-trade policy to limit carbon emissions.[151] In the 2000s, Senator John McCain proposed bills (such as the McCain-Lieberman Climate Stewardship Act) that would have regulated carbon emissions, but his position on climate change was unusual among high-ranking party members.[143] Some Republican candidates have supported the development of alternative fuels in order to achieve energy independence for the United States. Some Republicans support increased oil drilling in protected areas such as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a position that has drawn criticism from activists.[152]

Many Republicans during the presidency of Barack Obama opposed his administration's new environmental regulations, such as those on carbon emissions from coal. In particular, many Republicans supported building the Keystone Pipeline; this position was supported by businesses, but opposed by indigenous peoples' groups and environmental activists.[153][154][155]

According to the Center for American Progress, a non-profit liberal advocacy group, more than 55% of congressional Republicans were climate change deniers in 2014.[156][157] PolitiFact in May 2014 found "relatively few Republican members of Congress ... accept the prevailing scientific conclusion that global warming is both real and man-made". The group found eight members who acknowledged it, although the group acknowledged there could be more and that not all members of Congress have taken a stance on the issue.[158][159]

From 2008 to 2017, the Republican Party went from "debating how to combat human-caused climate change to arguing that it does not exist", according to The New York Times.[160] In January 2015, the Republican-led U.S. Senate voted 98–1 to pass a resolution acknowledging that "climate change is real and is not a hoax"; however, an amendment stating that "human activity significantly contributes to climate change" was supported by only five Republican senators.[161]

Immigration

In the period 1850–1870, the Republican Party was more opposed to immigration than Democrats, in part because the Republican Party relied on the support of anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant parties, such as the Know-Nothings, at the time. In the decades following the Civil War, the Republican Party grew more supportive of immigration, as it represented manufacturers in the Northeast (who wanted additional labor) whereas the Democratic Party came to be seen as the party of labor (which wanted fewer laborers to compete with). Starting in the 1970s, the parties switched places again, as the Democrats grew more supportive of immigration than Republicans.[162]

Republicans are divided on how to confront illegal immigration between a platform that allows for migrant workers and a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants (supported by establishment types), versus a position focused on securing the border and deporting illegal immigrants (supported by populists). In 2006, the White House supported and Republican-led Senate passed comprehensive immigration reform that would eventually allow millions of illegal immigrants to become citizens, but the House (also led by Republicans) did not advance the bill.[163] After the defeat in the 2012 presidential election, particularly among Latinos, several Republicans advocated a friendlier approach to immigrants. However, in 2016 the field of candidates took a sharp position against illegal immigration, with leading candidate Donald Trump proposing building a wall along the southern border. Proposals calling for immigration reform with a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants have attracted broad Republican support in some[which?] polls. In a 2013 poll, 60% of Republicans supported the pathway concept.[164]

Foreign policy and national defense

Some[who?] in the Republican Party support unilateralism on issues of national security, believing in the ability and right of the United States to act without external support in matters of its national defense. In general, Republican thinking on defense and international relations is heavily influenced by the theories of neorealism and realism, characterizing conflicts between nations as struggles between faceless forces of an international structure as opposed to being the result of the ideas and actions of individual leaders. The realist school's influence shows in Reagan's Evil Empire stance on the Soviet Union and George W. Bush's Axis of evil stance.[citation needed]

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, many[who?] in the party have supported neoconservative policies with regard to the War on Terror, including the 2001 war in Afghanistan and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The George W. Bush administration took the position that the Geneva Conventions do not apply to unlawful combatants, while other[which?] prominent Republicans strongly oppose the use of enhanced interrogation techniques, which they view as torture.[165]

Republicans have frequently advocated for restricting foreign aid as a means of asserting the national security and immigration interests of the United States.[166][167][168]

The Republican Party generally supports a strong alliance with Israel and efforts to secure peace in the Middle East between Israel and its Arab neighbors.[169][170] In recent years, Republicans have begun to move away from the two-state solution approach to resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[171][172] In a 2014 poll, 59% of Republicans favored doing less abroad and focusing on the country's own problems instead.[173]

According to the 2016 platform,[174] the party's stance on the status of Taiwan is: "We oppose any unilateral steps by either side to alter the status quo in the Taiwan Straits on the principle that all issues regarding the island's future must be resolved peacefully, through dialogue, and be agreeable to the people of Taiwan". In addition, if "China were to violate those principles, the United States, in accord with the Taiwan Relations Act, will help Taiwan defend itself".

Social policies

The Republican Party is generally associated with social conservative policies, although it does have dissenting centrist and libertarian factions. The social conservatives support laws that uphold their traditional values, such as opposition to same-sex marriage, abortion, and marijuana.[175] Most conservative Republicans also oppose gun control, affirmative action, and illegal immigration.[175][176]

Abortion and embryonic stem cell research

A majority of the party's national and state candidates are anti-abortion and oppose elective abortion on religious or moral grounds. While many advocate exceptions in the case of incest, rape or the mother's life being at risk, in 2012 the party approved a platform advocating banning abortions without exception.[177] There were not highly polarized differences between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party prior to the Roe v. Wade 1973 Supreme Court ruling (which made prohibitions on abortion rights unconstitutional), but after the Supreme Court ruling, opposition to abortion became an increasingly key national platform for the Republican Party.[23][178][179] As a result, Evangelicals gravitated towards the Republican Party.[23][178]

Most Republicans oppose government funding for abortion providers, notably Planned Parenthood.[180] This includes support for the Hyde Amendment.

Until its dissolution in 2018, Republican Majority for Choice, an abortion rights PAC, advocated for amending the GOP platform to include pro-abortion rights members.[181]

Although Republicans have voted for increases in government funding of scientific research, members of the Republican Party actively oppose the federal funding of embryonic stem cell research beyond the original lines because it involves the destruction of human embryos.[182][183][184][185]

Civil rights

Republicans are generally against affirmative action for women and some minorities, often describing it as a "quota system" and believing that it is not meritocratic and that it is counter-productive socially by only further promoting discrimination. Many[who?] Republicans support race-neutral admissions policies in universities, but support taking into account the socioeconomic status of the student.[186][187]

Gun ownership

Republicans generally support gun ownership rights and oppose laws regulating guns. Party members and Republican-leaning independents are twice more likely to own a gun than Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents.[188]

The National Rifle Association, a special interest group in support of gun ownership, has consistently aligned themselves with the Republican Party. Following gun control measures under the Clinton administration, such as the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the Republicans allied with the NRA during the Republican Revolution in 1994.[189] Since then, the NRA has consistently backed Republican candidates and contributed financial support, such as in the 2013 Colorado recall election which resulted in the ousting of two pro-gun control Democrats for two anti-gun control Republicans.[190]

In contrast, George H. W. Bush, formerly a lifelong NRA member, was highly critical of the organization following their response to the Oklahoma City bombing authored by CEO Wayne LaPierre, and publicly resigned in protest.[191]

Drugs

Republicans have historically supported the War on Drugs and oppose the legalization of drugs.[192] More recently, several[which?] prominent Republicans have advocated for the reduction and reform of mandatory sentencing laws with regards to drugs.[193]

LGBT issues

Republicans have historically opposed same-sex marriage, while being divided on civil unions and domestic partnerships, with the issue being one that many believe helped George W. Bush win re-election in 2004.[194] In both 2004[195] and 2006,[196] President Bush, Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, and House Majority Leader John Boehner promoted the Federal Marriage Amendment, a proposed constitutional amendment which would legally restrict the definition of marriage to heterosexual couples.[197][198][199] In both attempts, the amendment failed to secure enough votes to invoke cloture and thus ultimately was never passed. As more states legalized same-sex marriage in the 2010s, Republicans increasingly supported allowing each state to decide its own marriage policy.[200] As of 2014, most state GOP platforms expressed opposition to same-sex marriage.[201] The 2016 GOP Platform defined marriage as "natural marriage, the union of one man and one woman," and condemned the Supreme Court's ruling legalizing same-sex marriages.[202][203] The 2020 platform retained the 2016 language against same-sex marriage.[204][205][206]

However, public opinion on this issue within the party has been changing.[207] Following his election as president in 2016, Donald Trump stated that he had no objection to same-sex marriage or to the Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges.[91] In office, Trump was the first sitting Republican president to recognize LGBT Pride Month.[208] Conversely, the Trump administration banned transgender individuals from service in the United States military and rolled back other protections for transgender people which had been enacted during the previous Democratic presidency.[209]

The Republican Party platform opposed the inclusion of gay people in the military and opposed adding sexual orientation to the list of protected classes since 1992.[210][211][212] The Republican Party opposed the inclusion of sexual preference in anti-discrimination statutes from 1992 to 2004.[213] The 2008 and 2012 Republican Party platform supported anti-discrimination statutes based on sex, race, age, religion, creed, disability, or national origin, but both platforms were silent on sexual orientation and gender identity.[214][215] The 2016 platform was opposed to sex discrimination statutes that included the phrase "sexual orientation."[216][217]

A group of LGBT Republicans are the Log Cabin Republicans.[218]

Voting rights

Virtually all restrictions on voting have in recent years been implemented by Republicans. Republicans, mainly at the state level, argue that the restrictions (such as purging voter rolls, limiting voting locations, and prosecuting double voting) are vital to prevent voter fraud, claiming that voter fraud is an underestimated issue in elections. However, research has indicated that voter fraud is very uncommon, as civil and voting rights organizations often accuse Republicans of enacting restrictions to influence elections in the party's favor. Many laws or regulations restricting voting enacted by Republicans have been successfully challenged in court, with court rulings striking down such regulations and accusing Republicans of establishing them with partisan purpose.[219][220]

Democracy

Towards the end of the 1990s and in the early 21st century, the Republican Party increasingly resorted to "constitutional hardball" practices.[221][222][223]

A number of scholars have asserted that the House speakership of Republican Newt Gingrich played a key role in undermining democratic norms in the United States, hastening political polarization, and increasing partisan prejudice.[224][225][226][227][228][229][230][231][232][233][234][excessive citations] According to Harvard University political scientists Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, Gingrich's speakership had a profound and lasting impact on American politics and the health of American democracy. They argue that Gingrich instilled a "combative" approach in the Republican Party, where hateful language and hyper-partisanship became commonplace, and where democratic norms were abandoned. Gingrich frequently questioned the patriotism of Democrats, called them corrupt, compared them to fascists, and accused them of wanting to destroy the United States. Gingrich was also involved in several major government shutdowns.[228][235][236][237]

Scholars have also characterized Mitch McConnell's tenure as Senate Minority Leader and Senate Majority Leader during the Obama presidency as one where obstructionism reached all-time highs.[238] Political scientists have referred to McConnell's use of the filibuster as "constitutional hardball", referring to the misuse of procedural tools in a way that undermines democracy.[221][228][229][233] McConnell delayed and obstructed health care reform and banking reform, which were two landmark pieces of legislation that Democrats sought to pass (and in fact did pass[239]) early in Obama's tenure.[240][241] By delaying Democratic priority legislation, McConnell stymied the output of Congress. Political scientists Eric Schickler and Gregory J. Wawro write, "by slowing action even on measures supported by many Republicans, McConnell capitalized on the scarcity of floor time, forcing Democratic leaders into difficult trade-offs concerning which measures were worth pursuing. That is, given that Democrats had just two years with sizeable majorities to enact as much of their agenda as possible, slowing the Senate's ability to process even routine measures limited the sheer volume of liberal bills that could be adopted."[241]

McConnell's refusal to hold hearings on Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland during the final year of Obama's presidency was described by political scientists and legal scholars as "unprecedented",[242][243] a "culmination of this confrontational style",[244] a "blatant abuse of constitutional norms",[245] and a "classic example of constitutional hardball."[233] Senate Republicans justified this move by pointing to a 1992 speech from then-Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Joe Biden;[246][247] in that speech, Biden argued that hearings on any potential Supreme Court nominee that year should be postponed until after Election Day.[246][248] Biden contested this interpretation of his 1992 speech.[248]

Composition

In the Party's early decades, its base consisted of Northern white Protestants and African Americans nationwide. Its first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, received almost no votes in the South. This trend continued into the 20th century. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Southern states became more reliably Republican in presidential politics, while Northeastern states became more reliably Democratic.[249][250][251][252][253][254][255][256] Studies show that Southern whites shifted to the Republican Party due to racial conservatism.[255][257][258]

While scholars agree that a racial backlash played a central role in the racial realignment of the two parties, there is a dispute as to the extent in which the racial realignment was a top-driven elite process or a bottom-up process.[259] The "Southern Strategy" refers primarily to "top-down" narratives of the political realignment of the South which suggest that Republican leaders consciously appealed to many white Southerners' racial grievances in order to gain their support. This top-down narrative of the Southern Strategy is generally believed to be the primary force that transformed Southern politics following the civil rights era. Scholar Matthew Lassiter argues that "demographic change played a more important role than racial demagoguery in the emergence of a two-party system in the American South".[260][261] Historians such as Matthew Lassiter, Kevin M. Kruse and Joseph Crespino, have presented an alternative, "bottom-up" narrative, which Lassiter has called the "suburban strategy". This narrative recognizes the centrality of racial backlash to the political realignment of the South,[259] but suggests that this backlash took the form of a defense of de facto segregation in the suburbs rather than overt resistance to racial integration and that the story of this backlash is a national rather than a strictly Southern one.[262][263][264][265]

The Party's 21st-century base consists of groups such as older white men; white, married Protestants; rural residents; and non-union workers without college degrees, with urban residents, ethnic minorities, the unmarried and union workers having shifted to the Democratic Party. The suburbs have become a major battleground.[266] According to a 2015 Gallup poll, 25% of Americans identify as Republican and 16% identify as leaning Republican. In comparison, 30% identify as Democratic and 16% identify as leaning Democratic. The Democratic Party has typically held an overall edge in party identification since Gallup began polling on the issue in 1991.[267] In 2016, The New York Times noted that the Republican Party was strong in the South, the Great Plains, and the Mountain States.[268] The 21st century Republican Party also draws strength from rural areas of the United States.[269]

Ideology and factions

In 2018, Gallup polling found that 69% of Republicans described themselves as "conservative", while 25% opted for the term "moderate", and another 5% self-identified as "liberal".[270]

When ideology is separated into social and economic issues, a 2020 Gallup poll found that 61% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents called themselves "socially conservative", 28% chose the label "socially moderate", and 10% called themselves "socially liberal".[271] On economic issues, the same 2020 poll revealed that 65% of Republicans (and Republican leaners) chose the label "economic conservative" to describe their views on fiscal policy, while 26% selected the label "economic moderate", and 7% opted for the "economic liberal" label.[271]

The modern Republican Party includes conservatives,[2] centrists,[7] fiscal conservatives, libertarians,[8] neoconservatives,[8] paleoconservatives,[272] right-wing populists,[9][10] and social conservatives.[4][273][274][275]

In addition to splits over ideology, the 21st-century Republican Party can be broadly divided into establishment and anti-establishment wings.[276][277] Nationwide polls of Republican voters in 2014 by the Pew Center identified a growing split in the Republican coalition, between "business conservatives" or "establishment conservatives" on one side and "steadfast conservatives" or "populist conservatives" on the other.[278]

Talk radio

In the 21st century, conservatives on talk radio and Fox News, as well as online media outlets such as the Daily Caller and Breitbart News, became a powerful influence on shaping the information received and judgments made by rank-and-file Republicans.[279][280] They include Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Larry Elder, Glenn Beck, Mark Levin, Dana Loesch, Hugh Hewitt, Mike Gallagher, Neal Boortz, Laura Ingraham, Dennis Prager, Michael Reagan, Howie Carr and Michael Savage, as well as many local commentators who support Republican causes while vocally opposing the left.[281][282][283][284]

Business community

The Republican Party has traditionally been a pro-business party. It garners major support from a wide variety of industries from the financial sector to small businesses. Republicans are about 50 percent more likely to be self-employed and are more likely to work in management.[285][clarification needed]

A survey cited by The Washington Post in 2012 stated that 61 percent of small business owners planned to vote for Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Small business became a major theme of the 2012 Republican National Convention.[286]

Demographics

In 2006, Republicans won 38% of the voters aged 18–29.[287] In a 2018 study, members of the Silent and Boomer generations were more likely to express approval of Trump's presidency than those of Generation X and Millennials.[288]

Low-income voters are more likely to identify as Democrats while high-income voters are more likely to identify as Republicans.[289] In 2012, Obama won 60% of voters with income under $50,000 and 45% of those with incomes higher than that.[290] Bush won 41% of the poorest 20% of voters in 2004, 55% of the richest twenty percent and 53% of those in between. In the 2006 House races, the voters with incomes over $50,000 were 49% Republican while those with incomes under that amount were 38% Republican.[287]

Gender

Since 1980, a "gender gap" has seen stronger support for the Republican Party among men than among women. Unmarried and divorced women were far more likely to vote for Democrat John Kerry than for Republican George W. Bush in the 2004 presidential election.[291] In 2006 House races, 43% of women voted Republican while 47% of men did so.[287] In the 2010 midterms, the "gender gap" was reduced, with women supporting Republican and Democratic candidates equally (49%-49%).[292][293] Exit polls from the 2012 elections revealed a continued weakness among unmarried women for the GOP, a large and growing portion of the electorate.[294] Although women supported Obama over Mitt Romney by a margin of 55–44% in 2012, Romney prevailed amongst married women, 53–46%.[295] Obama won unmarried women 67–31%.[296] According to a December 2019 study, "white women are the only group of female voters who support Republican Party candidates for president. They have done so by a majority in all but 2 of the last 18 elections".[297]

Education

In 2012, the Pew Research Center conducted a study of registered voters with a 35–28, Democrat-to-Republican gap. They found that self-described Democrats had a +8 advantage over Republicans among college graduates, +14 of all post-graduates polled. Republicans were +11 among white men with college degrees, Democrats +10 among women with degrees. Democrats accounted for 36% of all respondents with an education of high school or less and Republicans were 28%. When isolating just white registered voters polled, Republicans had a +6 advantage overall and were +9 of those with a high school education or less.[298] Following the 2016 presidential election, exit polls indicated that "Donald Trump attracted a large share of the vote from whites without a college degree, receiving 72 percent of the white non-college male vote and 62 percent of the white non-college female vote". Overall, 52% of voters with college degrees voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, while 52% of voters without college degrees voted for Trump.[299]

Ethnicity

Republicans have been winning under 15% of the black vote in recent national elections (1980 to 2016). The party abolished slavery under Abraham Lincoln, defeated the Slave Power, and gave blacks the legal right to vote during Reconstruction in the late 1860s. Until the New Deal of the 1930s, blacks supported the Republican Party by large margins.[300] Black delegates were a sizable share of Southern delegates to the national Republican convention from Reconstruction until the start of the 20th century when their share began to decline.[301] Black voters began shifting away from the Republican Party after the close of Reconstruction through the early 20th century, with the rise of the southern-Republican lily-white movement.[302] Blacks shifted in large margins to the Democratic Party in the 1930s, when major Democratic figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt began to support civil rights and the New Deal offered them employment opportunities. They became one of the core components of the New Deal coalition. In the South, after the Voting Rights Act to prohibit racial discrimination in elections was passed by a bipartisan coalition in 1965, blacks were able to vote again and ever since have formed a significant portion (20–50%) of the Democratic vote in that region.[303]

In the 2010 elections, two African-American Republicans—Tim Scott and Allen West—were elected to the House of Representatives.[304]

In recent decades, Republicans have been moderately successful in gaining support from Hispanic and Asian American voters. George W. Bush, who campaigned energetically for Hispanic votes, received 35% of their vote in 2000 and 44% in 2004.[305] The party's strong anti-communist stance has made it popular among some minority groups from current and former Communist states, in particular Cuban Americans, Korean Americans, Chinese Americans and Vietnamese Americans. The 2007 election of Bobby Jindal as Governor of Louisiana was hailed as pathbreaking.[306] Jindal became the first elected minority governor in Louisiana and the first state governor of Indian descent.[307] According to John Avlon, in 2013, the Republican party was more ethnically diverse at the statewide elected official level than the Democratic Party was; GOP statewide elected officials included Latino Nevada Governor Brian Sandoval and African-American U.S. senator Tim Scott of South Carolina.[308]

In 2012, 88% of Romney voters were white while 56% of Obama voters were white.[309] In the 2008 presidential election, John McCain won 55% of white votes, 35% of Asian votes, 31% of Hispanic votes and 4% of African American votes.[310] In the 2010 House election, Republicans won 60% of the white votes, 38% of Hispanic votes and 9% of the African American vote.[311]

As of 2019, Republican candidates had lost the popular vote in six out of the last seven presidential elections.[312] Demographers have pointed to the steady decline (as a percentage of the eligible voters) of its core base of older, less educated men.[313][314][315][316]

Religious beliefs

Religion has always played a major role for both parties, but in the course of a century, the parties' religious compositions have changed. Religion was a major dividing line between the parties before 1960, with Catholics, Jews, and Southern Protestants heavily Democratic and Northeastern Protestants heavily Republican. Most of the old differences faded away after the realignment of the 1970s and 1980s that undercut the New Deal coalition.[317] Voters who attend church weekly gave 61% of their votes to Bush in 2004 and those who attend occasionally gave him only 47% while those who never attend gave him 36%. Fifty-nine percent of Protestants voted for Bush, along with 52% of Catholics (even though John Kerry was Catholic). Since 1980, a large majority of evangelicals have voted Republican; 70–80% voted for Bush in 2000 and 2004 and 70% for Republican House candidates in 2006. Jews continue to vote 70–80% Democratic. Democrats have close links with the African American churches, especially the National Baptists, while their historic dominance among Catholic voters has eroded to 54–46 in the 2010 midterms.[318] The mainline traditional Protestants (Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Episcopalians and Disciples) have dropped to about 55% Republican (in contrast to 75% before 1968).

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Utah and neighboring states voted 75% or more for George W. Bush in 2000.[319] Members of the Mormon faith have had a mixed relationship with Donald Trump since his taking office, despite them majorly voting for him in 2016 at 67% and supporting his presidency in 2018 at 56%, disapproving of his personal behavior such as that shown during the Access Hollywood controversy.[320] Their opinion on Trump hasn't affected their party affiliation, however, as 76% of Mormons in 2018 expressed preference for generic Republican congressional candidates.[321]

While Catholic Republican leaders try to stay in line with the teachings of the Catholic Church on subjects such as abortion, euthanasia, embryonic stem cell research and same-sex marriage, they differ on the death penalty and contraception.[322] Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical Laudato si' sparked a discussion on the positions of Catholic Republicans in relation to the positions of the Church. The Pope's encyclical on behalf of the Catholic Church officially acknowledges a man-made climate change caused by burning fossil fuels.[323] The Pope says the warming of the planet is rooted in a throwaway culture and the developed world's indifference to the destruction of the planet in pursuit of short-term economic gains. According to The New York Times, Laudato si' put pressure on the Catholic candidates in the 2016 election: Jeb Bush, Bobby Jindal, Marco Rubio and Rick Santorum.[324] With leading Democrats praising the encyclical, James Bretzke, a professor of moral theology at Boston College, has said that both sides were being disingenuous: "I think it shows that both the Republicans and the Democrats ... like to use religious authority and, in this case, the Pope to support positions they have arrived at independently ... There is a certain insincerity, hypocrisy I think, on both sides".[325] While a Pew Research poll indicates Catholics are more likely to believe the Earth is warming than non-Catholics, 51% of Catholic Republicans believe in global warming (less than the general population) and only 24% of Catholic Republicans believe global warming is caused by human activity.[326]

In 2016, a slim majority of Orthodox Jews voted for the Republican Party, following years of growing Orthodox Jewish support for the party due to its social conservatism and increasingly pro-Israel foreign policy stance.[327]

Republican presidents

As of 2020, there have been a total of 19 Republican presidents.

| # | President | Portrait | State | Presidency start date |

Presidency end date |

Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) |

|

Illinois | March 4, 1861 | April 15, 1865[a] | 4 years, 42 days |

| 18 | Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) |

|

Illinois | March 4, 1869 | March 4, 1877 | 8 years, 0 days |

| 19 | Rutherford B. Hayes (1822–1893) |

|

Ohio | March 4, 1877 | March 4, 1881 | 4 years, 0 days |

| 20 | James A. Garfield (1831–1881) |

|

Ohio | March 4, 1881 | September 19, 1881[a] | 199 days |

| 21 | Chester A. Arthur (1829–1886) |

|

New York | September 19, 1881 | March 4, 1885 | 3 years, 166 days |

| 23 | Benjamin Harrison (1833–1901) |

|

Indiana | March 4, 1889 | March 4, 1893 | 4 years, 0 days |

| 25 | William McKinley (1843–1901) |

|

Ohio | March 4, 1897 | September 14, 1901[a] | 4 years, 194 days |

| 26 | Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) |

|

New York | September 14, 1901 | March 4, 1909 | 7 years, 171 days |

| 27 | William Howard Taft (1857–1930) |

|

Ohio | March 4, 1909 | March 4, 1913 | 4 years, 0 days |

| 29 | Warren G. Harding (1865–1923) |

|

Ohio | March 4, 1921 | August 2, 1923[a] | 2 years, 151 days |

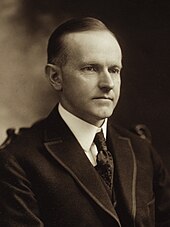

| 30 | Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933) |

|

Massachusetts | August 2, 1923 | March 4, 1929 | 5 years, 214 days |

| 31 | Herbert Hoover (1874–1964) |

|

California | March 4, 1929 | March 4, 1933 | 4 years, 0 days |

| 34 | Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969) |

|

Kansas | January 20, 1953 | January 20, 1961 | 8 years, 0 days |

| 37 | Richard Nixon (1913–1994) |

|

California | January 20, 1969 | August 9, 1974[b] | 5 years, 201 days |

| 38 | Gerald Ford (1913–2006) |

|

Michigan | August 9, 1974 | January 20, 1977 | 2 years, 164 days |

| 40 | Ronald Reagan (1911–2004) |

|

California | January 20, 1981 | January 20, 1989 | 8 years, 0 days |

| 41 | George H. W. Bush (1924–2018) |

|

Texas | January 20, 1989 | January 20, 1993 | 4 years, 0 days |

| 43 | George W. Bush (1946–) |

|

Texas | January 20, 2001 | January 20, 2009 | 8 years, 0 days |

| 45 | Donald Trump (1946–) |

|

New York | January 20, 2017 | Incumbent | 7 years, 343 days |

Electoral history

In congressional elections: 1950–present

| House Election year | No. of overall House seats won |

+/– | Presidency | No. of overall Senate seats won |

+/– | Senate Election year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 199 / 435

|

Harry S. Truman | 47 / 96

|

1950 | ||

| 1952 | 221 / 435

|

Dwight D. Eisenhower | 49 / 96

|

1952 | ||

| 1954 | 203 / 435

|

47 / 96

|

1954 | |||

| 1956 | 201 / 435

|

47 / 96

|

1956 | |||

| 1958 | 153 / 435

|

34 / 98

|

1958 | |||

| 1960 | 175 / 435

|

John F. Kennedy | 35 / 100

|

1960 | ||

| 1962 | 176 / 435

|

34 / 100

|

1962 | |||

| 1964 | 140 / 435

|

Lyndon B. Johnson | 32 / 100

|

1964 | ||

| 1966 | 187 / 435

|

38 / 100

|

1966 | |||

| 1968 | 192 / 435

|

Richard Nixon | 42 / 100

|

1968 | ||

| 1970 | 180 / 435

|

44 / 100

|

1970 | |||

| 1972 | 192 / 435

|

41 / 100

|

1972 | |||

| 1974 | 144 / 435

|

Gerald Ford | 38 / 100

|

1974 | ||

| 1976 | 143 / 435

|

Jimmy Carter | 38 / 100

|

1976 | ||

| 1978 | 158 / 435

|

41 / 100

|

1978 | |||

| 1980 | 192 / 435

|

Ronald Reagan | 53 / 100

|

1980 | ||

| 1982 | 166 / 435

|

54 / 100

|

1982 | |||

| 1984 | 182 / 435

|

53 / 100

|

1984 | |||

| 1986 | 177 / 435

|

46 / 100

|

1986 | |||

| 1988 | 175 / 435

|

George H. W. Bush | 45 / 100

|

1988 | ||

| 1990 | 167 / 435

|

44 / 100

|

1990 | |||

| 1992 | 176 / 435

|

Bill Clinton | 43 / 100

|

1992 | ||

| 1994 | 230 / 435

|

53 / 100

|

1994 | |||

| 1996 | 227 / 435

|

55 / 100

|

1996 | |||

| 1998 | 223 / 435

|

55 / 100

|

1998 | |||

| 2000 | 221 / 435

|

George W. Bush | 50 / 100

|

2000 | ||

| 2002 | 229 / 435

|

51 / 100

|

2002 | |||

| 2004 | 232 / 435

|

55 / 100

|

2004 | |||

| 2006 | 202 / 435

|

49 / 100

|

2006 | |||

| 2008 | 178 / 435

|

Barack Obama | 41 / 100

|

2008 | ||

| 2010 | 242 / 435

|

47 / 100

|

2010 | |||

| 2012 | 234 / 435

|

45 / 100

|

2012 | |||

| 2014 | 247 / 435

|

54 / 100

|

2014 | |||

| 2016 | 241 / 435

|

Donald Trump | 52 / 100

|

2016 | ||

| 2018 | 199 / 435

|

53 / 100

|

2018 | |||

| 2020 | 0 / 435

|

TBD | TBD | 0 / 100

|

TBD | 2020 |

In presidential elections: 1856–present

| Election | Candidate | Votes | Vote % | Electoral votes | +/– | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1856 | John C. Frémont | 1,342,345 | 33.1 | 114 / 296

|

Lost | |

| 1860 | Abraham Lincoln | 1,865,908 | 39.8 | 180 / 303

|

Won | |

| 1864 | Abraham Lincoln | 2,218,388 | 55.0 | 212 / 233

|

Won | |

| 1868 | Ulysses S. Grant | 3,013,421 | 52.7 | 214 / 294

|

Won | |

| 1872 | Ulysses S. Grant | 3,598,235 | 55.6 | 286 / 352

|

Won | |

| 1876 | Rutherford B. Hayes | 4,034,311 | 47.9 | 185 / 369

|

Won[C] | |

| 1880 | James A. Garfield | 4,446,158 | 48.3 | 214 / 369

|

Won | |

| 1884 | James G. Blaine | 4,856,905 | 48.3 | 182 / 401

|

Lost | |

| 1888 | Benjamin Harrison | 5,443,892 | 47.8 | 233 / 401

|

Won[D] | |

| 1892 | Benjamin Harrison | 5,176,108 | 43.0 | 145 / 444

|

Lost | |

| 1896 | William McKinley | 7,111,607 | 51.0 | 271 / 447

|

Won | |

| 1900 | William McKinley | 7,228,864 | 51.6 | 292 / 447

|

Won | |

| 1904 | Theodore Roosevelt | 7,630,457 | 56.4 | 336 / 476

|

Won | |

| 1908 | William Howard Taft | 7,678,395 | 51.6 | 321 / 483

|

Won | |

| 1912 | William Howard Taft | 3,486,242 | 23.2 | 8 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1916 | Charles E. Hughes | 8,548,728 | 46.1 | 254 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1920 | Warren G. Harding | 16,144,093 | 60.3 | 404 / 531

|

Won | |

| 1924 | Calvin Coolidge | 15,723,789 | 54.0 | 382 / 531

|

Won | |

| 1928 | Herbert Hoover | 21,427,123 | 58.2 | 444 / 531

|

Won | |

| 1932 | Herbert Hoover | 15,761,254 | 39.7 | 59 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1936 | Alf Landon | 16,679,543 | 36.5 | 8 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1940 | Wendell Willkie | 22,347,744 | 44.8 | 82 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1944 | Thomas E. Dewey | 22,017,929 | 45.9 | 99 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1948 | Thomas E. Dewey | 21,991,292 | 45.1 | 189 / 531

|

Lost | |

| 1952 | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 34,075,529 | 55.2 | 442 / 531

|

Won | |

| 1956 | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 35,579,180 | 57.4 | 457 / 531

|

Won | |

| 1960 | Richard Nixon | 34,108,157 | 49.6 | 219 / 537

|

Lost | |

| 1964 | Barry Goldwater | 27,175,754 | 38.5 | 52 / 538

|

Lost | |

| 1968 | Richard Nixon | 31,783,783 | 43.4 | 301 / 538

|

Won | |

| 1972 | Richard Nixon | 47,168,710 | 60.7 | 520 / 538

|

Won | |

| 1976 | Gerald Ford | 38,148,634 | 48.0 | 240 / 538

|

Lost | |

| 1980 | Ronald Reagan | 43,903,230 | 50.7 | 489 / 538

|

Won | |

| 1984 | Ronald Reagan | 54,455,472 | 58.8 | 525 / 538

|

Won | |

| 1988 | George H. W. Bush | 48,886,097 | 53.4 | 426 / 538

|

Won | |

| 1992 | George H. W. Bush | 39,104,550 | 37.4 | 168 / 538

|

Lost | |

| 1996 | Bob Dole | 39,197,469 | 40.7 | 159 / 538

|

Lost | |

| 2000 | George W. Bush | 50,456,002 | 47.9 | 271 / 538

|

Won[E] | |

| 2004 | George W. Bush | 62,040,610 | 50.7 | 286 / 538

|

Won | |

| 2008 | John McCain | 59,948,323 | 45.7 | 173 / 538

|

Lost | |

| 2012 | Mitt Romney | 60,933,500 | 47.2 | 206 / 538

|

Lost | |

| 2016 | Donald Trump | 62,984,825 | 46.1 | 304 / 538

|

Won[F] | |

| 2020 | Donald Trump[329] | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA |

Groups supporting the Republican Party

- Club for Growth

- Concerned Women for America

- Eagle Forum

- Family Research Council

- Gun Owners of America

- Maggie's List

- National Right to Life Committee

- National Rifle Association

- National Association for Gun Rights

- Republican Jewish Coalition

- Susan B. Anthony List

- Senate Conservatives Fund

See also

- Factions in the Republican Party

- List of African-American Republicans

- List of Hispanic and Latino Republicans

- List of state parties of the Republican Party (United States)

- List of United States Republican Party presidential tickets

- Political party strength in U.S. states

- Republican In Name Only

- South Park Republican

Notes

- ^ All major Republican geographic constituencies are visible: red dominates the map—showing Republican strength in the rural areas—while the denser areas (i.e. cities) are blue. Notable exceptions include the Pacific coast, New England, the Southern United States, areas with high Native American populations and the heavily Hispanic parts of the Southwest

- ^ Similar to the 2004 map, Republicans dominate in rural areas, making improvements in the Appalachian states, namely Kentucky, where the party won all but two counties; and West Virginia, where every county in the state voted Republican. The party also improved in many rural counties in Iowa, Wisconsin and other Midwestern states. Contrarily, the party suffered substantial losses in urbanized areas such Dallas, Harris and Fort Bend counties in Texas and Orange and San Diego counties in California, all of which were won in 2004, but lost in 2016

- ^ Although Hayes won a majority of votes in the Electoral College, Democrat Samuel J. Tilden won a majority of the popular vote.

- ^ Although Harrison won a majority of votes in the Electoral College, Democrat Grover Cleveland won a plurality of the popular vote.

- ^ Although Bush won a majority of votes in the Electoral College, Democrat Al Gore won a plurality of the popular vote.

- ^ Although Trump won a majority of votes in the Electoral College, Democrat Hillary Clinton won a plurality of the popular vote.

References

- ^ Winger, Richard. "March 2020 Ballot Access News Print Edition". Ballot Access News. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Paul Gottfried, Conservatism in America: Making Sense of the American Right, p. 9, "Postwar conservatives set about creating their own synthesis of free-market capitalism, Christian morality, and the global struggle against Communism." (2009); Gottfried, Theologies and moral concern (1995) p. 12.

- ^ Kurth, James (2016). American Conservatism: NOMOS LVI. New York University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9781479812370.

- ^ a b "No Country for Old Social Conservatives?". thecrimson.com. Nair. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ "Social conservatives win on GOP platform". Politico. July 18, 2016. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Republican Party". History. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Siegel, Josh (July 18, 2017). "Centrist Republicans and Democrats meet to devise bipartisan healthcare plan". The Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Miller, William J. (2013). The 2012 Nomination and the Future of the Republican Party. Lexington Books. p. 39.

- ^ a b Cassidy, John (February 29, 2016). "Donald Trump is Transforming the G.O.P. Into a Populist, Nativist Party". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Gould, J.J. (July 2, 2016). "Why Is Populism Winning on the American Right?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "About". ECR Party. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Members". IDU. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015.

- ^ "International Democrat Union » APDU". International Democrat Union. May 22, 2018. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015.

- ^ Joseph R. Fornieri; Sara Vaughn Gabbard (2008). Lincoln's America: 1809–1865. SIU Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780809387137. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ James G. Randall; Lincoln the Liberal Statesman (1947).

- ^ "The Ol' Switcheroo. Theodore Roosevelt, 1912". Time. April 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Zingher, Joshua N. (2018). "Polarization, Demographic Change, and White Flight from the Democratic Party". The Journal of Politics. 80 (3): 860–72. doi:10.1086/696994. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ^ "1. Trends in party affiliation among demographic groups". Pew Research Center. March 20, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "Presidential Election Results: Donald J. Trump Wins". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (October 28, 2018). "Religion and Right-Wing Politics: How Evangelicals Reshaped Elections" – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Cohen, Marty (April 24, 2019). "Evangelicals are now the key constituency in the Republican Party. They are reaping the benefits". Vox.

- ^ "GOP–Immigration". Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c Layman, Geoffrey (2001). The Great Divide: Religious and Cultural Conflict in American Party Politics. Columbia University Press. pp. 115, 119–20. ISBN 978-0231120586. Archived from the original on June 25, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- ^ William Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 (Oxford UP, 1987)

- ^ William Gienapp, "Nativism and the Creation of a Republican Majority in the North before the Civil War." Journal of American History 72.3 (1985): 529-559 online

- ^ "U.S. Senate: The Kansas-Nebraska Act". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ "The Wealthy Activist Who Helped Turn "Bleeding Kansas" Free". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ "The Origin of the Republican Party, A. F. Gilman, Ripon College, 1914". Content.wisconsinhistory.org. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ^ "History of the GOP". GOP. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ "Birth of Republicanism" (PDF). NY Times.

- ^ "Republican National Political Conventions 1856-2008 (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ a b s. "First Republican national convention ends". HISTORY. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ s. "Lincoln reelected". HISTORY. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Klein, Christopher. "Congress Passes 13th Amendment, 150 Years Ago". HISTORY. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (July 20, 2016). "Donald Trump and Chris Christie are reportedly planning to purge the civil service". Vox. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Andrew Glass. "Pendleton Act inaugurates U.S. civil service system, Jan. 16, 1883". POLITICO.

- ^ "Chester A. Arthur".