Elrhaz Formation

| Elrhaz Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Aptian-Albian ~ | |

Outcrops of the formation near Gadoufaoua | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Tegama Group |

| Underlies | Echkar Formation |

| Overlies | Tazolé Formation |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 16°48′N 9°30′E / 16.8°N 9.5°E |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 3°06′N 4°54′E / 3.1°N 4.9°E |

| Region | Africa |

| Country | |

| Extent | Tenere desert |

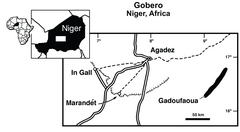

The Elrhaz Formation is a geological formation in Niger, central Africa.

Its strata date back to the Early Cretaceous (late Aptian to early Albian stages, about 112 million years ago). Dinosaur remains are among the fossils that have been recovered from the formation, alongside those of multiple species of crocodyliformes.

Gadoufaoua

Gadoufaoua (Tuareg for "the place where camels fear to go") is a site within the Elrhaz Formation (located at 16°50′N 9°25′E / 16.833°N 9.417°E) in the Tenere desert of Niger known for its extensive fossil graveyard. It is where remains of Sarcosuchus imperator, popularly known as SuperCroc, were found (by Paul Sereno in 1997, for example), including vertebrae, limb bones, armor plates, jaws, and a nearly complete 6 feet (1.8 m) skull.

Gadoufaoua is very hot and dry. However, it is supposed that millions of years ago, Gadoufaoua had trees, plants and wide rivers. The river covered the remains of dead animals, the fossilized remains of which were protected by the drying rivers over millions of years.[1]

Vertebrate paleofauna

Fossils of the turtles Laganemys tenerensis and Taquetochelys decorata were found in the formation.[2]

Crocodyliformes

| Crocodyliformes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Material | Notes | Images |

| Araripesuchus[3] | A. wegeneri[3] | (1959) "nearly complete skull" - Sereno & Larsson (1999) | Pseudonym. Dog-Croc |  |

| Anatosuchus[3] | A. minor[3] | (2003) "nearly complete skull" - Sereno & Larsson (1999) | Pseudonym. Duck-Croc |  |

| Sarcosuchus[4] | S. imperator | "partial skeletons, numerous skulls" | (1966) |  |

Ornithischians

| Ornithischians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

| Lurdusaurus[3] | L. arenatus[3] | (1999) | "Partial skull, fragmentary postcranial skeleton."[5] |  | |

| Ouranosaurus[3] | O. nigeriensis[3] | (1976) | "Skull and poscrania, second skeleton."[6] |  | |

| Elrhazosaurus[3] | E. nigeriensis[3] | (2009) | "Femora."[7] | A dryosaurid |  |

Theropods

| Theropods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

| Afromimus | A. tenerensis | (2017) | "caudal vertebrae, chevrons and portions of the right hind limb"[8] | A Noasaurid | |

| Eocarcharia[3] | E. dinops[9] | (2008) | "Partial skull and postcranial remains."[10] | Carcharodontosaurid |  |

| Suchomimus[3] | S. tenerensis[3] | (1998) | Partial skull and associated skeleton.[11] | A second, possible spinosaurid found in the formation, Cristatusaurus, is considered either a separate species or a synonym to Suchomimus[12] |  |

| Kryptops[3] | K. palaios[3] | (2008) | Postcranial skeleton and partial skull.[13] | Abelisaurid |  |

Sauropods

| Sauropods | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Material | Images |

| Nigersaurus | N. taqueti | The limited understanding of the genus was the result of poor preservation of its remains, which arises from the delicate and highly pneumatic construction of the skull and skeleton, in turn causing disarticulation of the fossils. Some of the skull fossils were so thin that a strong light beam was visible through them. Therefore, no intact skulls or articulated skeletons have been found, and these specimens represent the most complete known rebbachisaurid remains. |  |

See also

References

- ^ SCIENCE IN THE NEWS - Nov. 13: Digest - 12 November 2001 Voice of America

- ^ Laganemys type, Gadoufaoua at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "68.1 Departement D'Agedez, Niger; 1. Elrhaz Formation," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 572

- ^ Sereno et al., 2011

- ^ "Table 19.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 416.

- ^ "Table 19.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 417.

- ^ "Table 19.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 415.

- ^ Sereno, P. (2017). "Early Cretaceous ornithomimosaurs (Dinosauria: Coelurosauria) from Africa". Ameghiniana. 54 (5): 576–616. doi:10.5710/AMGH.23.10.2017.3155.

- ^ Sereno & Brusatte, 2008

- ^ "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 73.

- ^ "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 72.

- ^ Rauhut, O.W.M. (2003). "The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs". Special Papers in Palaeontology 69: 1-213.

- ^ "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2008). Page 72.

Bibliography

- Template:Cite LSA doi:10.1126/science.1066521ISSN 0036-8075PMID 11679634

- Template:Cite LSA

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2

Further reading

- P. M. Galton and P. Taquet. 1982. Valdosaurus, a hypsilophodontid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Europe and Africa. Géobios 15(2):147-159

- H. C. E. Larsson and B. Gado. 2000. A new Early Cretaceous crocodyliform from Niger. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 217(1):131-141

- P. C. Sereno and S. J. ElShafie. 2013. A New Long-Necked Turtle, Laganemys tenerensis (Pleurodira: Araripemydidae), from the Elrhaz Formation (Aptian–Albian) of Niger. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles 215-250

- P. C. Sereno and H. C. E. Larsson. 2009. Cretaceous crocodyliformes from the Sahara. ZooKeys 28:1-143

- P. C. Sereno, A. L. Beck, D. B. Dutheil, B. Gado, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, J. D. Marcot, O. W. M. Rauhut, R. W. Sadleir, C. A. Sidor, D. D. Varricchio, G. P. Wilson, and J. A. Wilson. 1998. A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids. Science 282:1298-1302