Kebaya

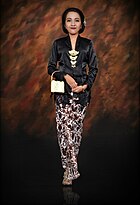

The classic Javanese kebaya is a sheer delicate tight-fitting blouse worn over kemben torso wrap of batik cloth, as shown here worn by Gusti Kanjeng Ratu Hayu, Princess of Yogyakarta | |

| Type | Traditional Blouse-dress |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Indonesia |

A kebaya is an Indonesian traditional blouse-dress combination that originated from the court of the Indonesian Kingdom in island of Java, and is traditionally worn by women in Indonesia and become a national dress. Kebaya is also used outside of Indonesia, like Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Southern Thailand, Cambodia and the southern part of the Philippines.

Kebaya is described as women's upper long-sleeved clothes.[1] It is sometimes made from sheer material such as silk, thin cotton or semi-transparent nylon or polyester, adorned with brocade or floral pattern embroidery. A kebaya is usually worn with a sarong, or a batik kain panjang — a long cloth wrapped around the waist,[1] or other traditional woven garment such as ikat, songket with a colorful motif.

The kebaya is the national costume of Indonesia,[2] although it is more accurately endemic to the Javanese, Sundanese (Java Island) and Balinese peoples.[3]

Etymology

While "kebaya" has a folk etymology from Template:Lang-ar qabāʼ "a long-sleeved upper garment",[4][5] the term is probably actually derived from عباءة ʽabāʼah, a cloak or loose outer garment. The term was then introduced into the archipelago through the Portuguese intermediary loanword cabaya.[6][7]

History

The earliest form of Kebaya believed was originates in the court of the 15th century Javanese Majapahit Kingdom, as a means to blend the existing female kemban, torso wrap of the aristocratic women, to be more modest and acceptable. Prior to Islamic influence, Javanese already recognised several term to describe clothings, such as kulambi (clothes), sarwul (pants), and ken (kain or long fabric wrapped around the waist).[6] During the last period of Majapahit kingdom, Islamic influence began to grow in coastal Javanese towns, thus there was a need to adapt the Javanese fashion to the newly adopted Islam religion. The tailored blouse, often made from delicate sheer fabrics, were worn over kemban torso wrap to cover the back, shoulders and arms, in order for court ladies to appear more modest. The adoption of a more modest fashion was attributed to the Islamic influence upon the archipelago.[6] Aceh, Riau and Johor Kingdoms and Northern Sumatra adopted the Javanese style kebaya as a means of social expression of status with the more alus or refined Javanese overlords.[8]

The name of Kebaya as a particular clothing type was noted by the Portuguese when they landed in Indonesia. Kebaya is associated with a type of blouse worn by Indonesian women in 15th or 16th century. Prior to 1600, kebaya on Java island were considered as a reserved clothing to be worn only by royal family, aristocrats (bangsawan) and minor nobility, in an era when peasant men and many women walked publicly bare-chested.

Later on, the kebaya also being adopted by commoners, the peasant women in Java. Up until this day in rural agricultural villages of Java, farmer women still uses simple kebaya, especially among elderly women. The everyday kebaya worn by peasant were of simple materials and secured with simple pin or peniti (safety pin).

Slowly it naturally spread to neighbouring areas through trade, diplomacy and social interactions to Malacca, Bali, Sumatra, Borneo, Sulawesi and the Sultanate of Sulu and Mindanao.[9][10][11] Javanese kebaya as known today were noted by Stamford Raffles in 1817, as being of silk, brocade and velvet, with the central opening of the blouse fastened by brooches, rather than button and button-holes over the torso wrap kemben, the kain — an unstitched wrap fabric several metres long, erroneously termed sarong in English (a sarung, Malaysian accent: sarong) which is stitched to form a tube.

The earliest photographics evidence of the kebaya as known today date from 1857 of Javanese, Peranakan and Oriental styles.[8] By the last quarter of the 19th century, kebaya had been adopted as the preferred women's fashion of the tropical Dutch East Indies, either worn by native Javanese, European colonials and Indos, also Chinese Peranakans.[12]

After hundreds of years of regional acculturation, the garments have become highly localised expressions of ethnic culture, artistry and tailoring traditions.

By 2019, there is a surge of kebaya popularity among modern Indonesian women. At MRT Station in Jakarta, a number of kebaya enthusiasts campaigned to promote kebaya as everyday fashion for work as well as for casual clothing on weekend. The movement sought to make wearing kebaya the norm among Indonesian women.[2]

Costume components

The quintessential kebaya is the Javanese kebaya as known today is essentially unchanged as noted by Raffles in 1817.[13][14] It consists of the blouse (kebaya) of cotton, silk, lace, brocade or velvet, with the central opening of the blouse fastened by a central brooch (kerongsang) where the flaps of the blouse meet, wore over kain.

- Kebaya blouse

- The kebaya blouse is commonly semi-transparent and traditionally worn over the torso wrap or kemben. Kebaya blouse can be tailored tight-fitting or loose-fitting, made from various materials, from cotton or velvet, to fine silk, exquisite lace and brocade, decorated with stitching or glittering sequins.

- Undergarments

- Because many of kebaya fabrics are made of fine, sheer and semi-transparent materials, there is a need to wear undergarments beneath to cover the breasts for modesty purpose. Traditionally, Javanese women wearing kemben torso wrap beneath their kebaya. Today however, the undergarment use under kebaya usually either corset, bra or camisole with matching colour. The more simple and modest undergarment wore by common village women, usually elderly women, is called kutang, which is a bra-like undergarment made from cotton.

- Kerongsang brooch

- Traditional kebaya had no buttons down the front. To secure the blouse openings in the front, a decorative metal brooch is applied on the chest. It can be made from brass, iron, silver or gold, decorated with semi-precious stones. A typical three-piece kerongsang is composed of a kerongsang ibu (mother piece) that is larger and heavier than the other two kerongsang anak (child piece). Kerongsang brooch often made from gold jewelry and considered as the sign of social status of aristocracy, wealth and nobility, however for commoners and peasant women, simple and plain kebaya often only fastened with modest safety pin (peniti).

- Kain sarong or skirt

- Kain is a long decorated clothes wrapped around the hips, secured with rope and wore as a kind of sarong or skirt. The skirt or kain is an unstitched fabric wrap around three metres long. The term sarong in English is erroneous, the sarung (Malaysian accent: sarong) is actually stitched together to form a tube, kain is unstitched, requires a helper to dress (literally wrap) the wearer and is held in place with a string (tali), then folded this string at the waist, then held with a belt (sabuk or ikat pinggang), which may hold a decorative pocket. In Java, Bali and Sunda, the kain is commonly batik which may be from plain stamped cotton to elaborately hand-painted batik tulis embroidered silk with gold thread. In Lampung, the kain is the traditional tapis, an elaborate gold-thread embroidered ikat with small mica discs.[15] Sumatra, Flores, Lemata Timor, and other islands commonly use kain of ikat or songket. Sumba is famous for kain decorated with lau hada: shells and beads.[16]

Variants of Kebaya elements

- Collars

- In the aspect of collar or neck cut, there are two main varieties; the V shaped collar (Javanese, Kartini, Balinese, and Encim or Peranakan) and the square collar cut (Kutubaru). The Sundanese and modern kebaya has U shaped collar edged with brocade and often decorated with sequins. Modern kebaya also might apply various shapes and curves of collars.

- Fabrics

- In fabrics aspect, the blouse known as baju kebaya may be of two main forms: the transparent or semi-transparent straighter cut blouse of Java, Bali, or the more plain and modest kebaya of Sumatra and Malaya.

- Cut and fittings

- In the cut aspect, two main varieties are; the more tightly tailored Java, Bali and Sunda kebaya, and the loose-fitting modest kebaya wore by more pious Muslim women, usually wore with hijab. The more Islamic compatible, a plainer and modest baju kurung is a loose-fitting, knee-length long-sleeved blouse worn in the more Muslim areas, including the former Kingdom of Johor-Riau (now Malaysia), Sumatra, Brunei and parts of coastal Borneo and Java.

Varieties

Kebaya Kartini

The type of kebaya used by aristocratic Javanese women, especially during the lifetime of Raden Ajeng Kartini, circa 19th century.[17] Often the term "Javanese kebaya" is synonymous with the kebaya Kartini, although slightly different. Kebaya Kartini usually made from a fine but non-transparent fabrics, and white is a favoured colour. Basic Kebaya Kartini might be plain. The adornment is quite minimal, only stitching or applied laces along the edges. The V-shaped collar cut of this type of kebaya is quite similar to the Peranakan Encim kebaya, however it is distinguishes by its distinctive fold on the chest. Another feature of the Kartini kebaya is the length of the kebaya that covers the hips, and the collar folds with a vertical line shape, which creates the tall and slender impression of the wearer.[18] The Kartini-style kebaya inspired the cut and style of Garuda Indonesia's flight attendants' uniform.

Kebaya Jawa

This type of kebaya from Java has a simple shape with a V-neck. This straight and simple cut gives an impression of simple elegance. Usually a Javanese kebaya is made of semi-transparent fine fabric patterned with floral stitching or embroidery, sometimes adorned with sequins. Other fabrics might be used, including cotton, brocade, silk and velvet. The semi-transparent kebaya is worn over matching underwear, either corset, bra or camisole.[18]

Kebaya Sunda

Tight-fitting brocade Sundanese kebaya allows more freedom in design, and much applied in modern kebaya and wedding kebaya in Indonesia. The semi-transparent fabrics is patterned with floral stitching or embroidery. The main difference with other kebaya style is the U collar neckline, often applying broad curves to cover shoulders and chest. Another difference is the extra long lower parts of kebaya, with hanging edges which covers hips and thigh. The contemporary wedding kebaya dress even has sweeping long train.

Kebaya Bali

Balinese kebaya is quite similar to Javanese kebaya, but slightly different. The Balinese kebaya usually has V neck line with folded collar sometimes decorated with laces. They are usually tight-fitting made with colorful semi-transparent or plain fabrics either cotton or brocade, patterned with floral stitching or embroidery. Unlike traditional Javanese kebaya, Balinese kebaya might add buttons in the front opening, and kerongsang brooch is seldom used. The main difference is Balinese kebaya add obi-like sash upon kebaya, wrap around the waist.[18]

Kebaya Kutubaru

The basic form of Kutubaru kebaya is quite similar to other types of kebaya.[17] What distinguishes it is the additional fabric called bef to connect the left and right side of the kebaya in the chest and abdomen. This create a square or rectangle shaped collar. This type of kebaya was meant to recreate the look of unsecured kebaya wore over matching kemben (torso wrap) undergarment. Kebaya Kutubaru is believed to be originated from Central Java.[19] Usually to wear this type of kebaya, stagen (cloth wrapped around the stomach), or rubber-enforced black corset is wore under the kebaya, thus the wearer will look more slender.[18]

The Balinese kebaya is part of busana adat or customary dress, Balinese women are required to wear kebaya during Balinese Hindu rituals and ceremony in pura. White kebaya are favoured for Balinese religious rituals. Other than religious ceremony, contemporary Balinese women also often wear kebaya for their daily activities. Because most Balinese people are Hindus, the Balinese kebaya usually has shorter sleeves compared to Javanese kebaya.

Kebaya Encim or Peranakan

In Java, the kebaya worn by ladies of Chinese ancestry is called kebaya encim, derived from the name encim or enci to refer to a married Chinese woman.[20] It was commonly worn by Chinese ladies in Javan coastal cities with significant Chinese settlements, such as Semarang, Lasem, Tuban, Surabaya, Pekalongan and Cirebon. It marked differently from Javanese kebaya with its smaller and finer embroidery, lighter fabrics and more vibrant colors, made from imported materials such as silk and other fine fabrics. The encim kebaya fit well with vibrant-colored kain batik pesisiran (Javan coastal batik).[17]

In Malacca, Malaysia, a different variety of kebaya is called "nyonya kebaya" and worn by those of Chinese ancestry: the Peranakan people. The Nyonya kebaya is different in its famously intricately hand-beaded shoes (kasut manek) and use of kain with Chinese motive batik or imported printed or hand-painted Chinese silks. Other than Malacca, the nyonya kebaya is also popular in other straits settlements of Penang and Singapore. The similar Nyonya Kebaya can also be found Phuket, where they shared the similar Peranakan culture with the historical Strait Settlements.

Kebaya Noni or Indo

Kebaya Indo is also known as kebaya Noni, derived from the term noni or nona which literally means "miss" to refer a young girl or unmarried woman of European descent.[17] During the Dutch East Indies era of Indonesia, Indo (Eurasian) women also colonial European women of high status adopted the kebaya, which provided less restrictive and cooler clothing, as a formal or social dress. Colonial ladies abandon their tight corset and wear light and comfortable undergarment under their kebaya. Indos and colonials probably adopted kebaya inherited from the clothing worn by Njai, native women kept as housekeepers, companions, and concubines in the colonial households. Njai ladies were the ancestors of Indo people (mixed European and Asian ancestry).

The cut and style of kebaya worn by the Dutch and Indo ladies were actually derived from Javanese kebaya. Nevertheless, there are some slight differences, European women wore shorter sleeves and total length cotton in prints, adorned with laces often imported from Europe. The kebaya worn by colonials and Indo ladies mostly are white and has light fabrics, this was meant to provide pleasant and cooler clothing in hot and humid tropical climate, since dark colored fabrics attract and retain heat.

The day kebaya of the Indo people was of white cotton trimmed with oriental motif handmade lace, either locally made in East Indies, or imported from Bruges or the Netherlands. While black silk kebaya is used for evening wear.

Political significance

In WWII internment camps of the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, Indonesian female prisoners refused to wear the western dress allocated them and instead wore kebaya as a display of nationalist and racial solidarity to separate them from fellow Chinese, Europeans and Eurasian inmates.[21]

The only woman present during Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, Dutch-educated activist S. K. Trimurti wore kebaya, cementing it as the female dress of Nationalism.

After Indonesian independence, Sukarno appointed kebaya as a national costume of Indonesian women.[19] Kebayas as the national costume of Indonesian women were often featured by Indonesian first ladies. Fatmawati and Dewi Sukarno, the wives of Sukarno, Indonesia's first president, were known to wear kebaya everyday.

The 21st of April is celebrated in Indonesia as National Kartini Day where Kartini, the female suffragist and education advocate, is remembered by schoolgirls wearing traditional dress according to their region. In Java, Bali and Sunda, it is the kebaya.[3]

The Suharto-era bureaucrat wives' social organisation Dharma Wanita wears a uniform of gold kebaya, with a red sash (selendang) and stamped batik pattern on the kain unique to Dharma Wanita. The late Indonesian first lady and also a minor aristocrat Siti Hartinah was a prominent advocate of the kebaya.

Former President Megawati Sukarnoputri is a public champion of kebaya and wears fine red kebaya whenever possible in public forums and 2009 Presidential election debates.

Modern usage and innovations

Kebaya has been one of the important parts of oriental style of clothing that heavily influenced the world of modern fashion. Lace dresses are one of the best examples of Kebaya influence.

Apart from traditional kebaya, fashion designers are looking into ways of modifying the design and making kebaya a more fashionable outfit. Casual designed kebaya can even be worn with jeans or skirts. For weddings or formal events, many designers are exploring other types of fine fabrics like laces to create a bridal kebaya.

Modern-day kebaya now incorporate modern tailoring innovations such as clasps, zippers and buttons zippers, being a much appreciated addition for ladies' that promptly need a toilet break, without requiring being literally unwrapped by a helper—to the extent the true traditional kain is near unanimously rejected. Other modern innovations have included the blouse baju kebaya worn without the restrictive kemben, and even the kebaya blouse worn with slacks or made of the fabric usually for the kain panjang. The female flight attendants of Malaysia Airlines and Singapore Airlines also feature batik kebaya as their uniforms.

The female uniform of Garuda Indonesia flight attendants is a more authentic modern interpretation. The kebaya is designed in simple yet classic Kartini-style kebaya derived from 19th century kebaya of Javanese noblewomen. The kebaya made from fire-proof cotton-polyester fabrics, with batik sarongs in parang or lereng gondosuli motif, which also incorporate garuda wing motifs and small dots representing jasmine.[22]

Currently, Indonesia is making efforts for kebaya to be recognised as a Intangible Cultural Heritage to the UNESCO. Efforts including "Selasa Berkebaya" (Tuesday Kebaya) movement among Indonesian women to popularise the daily use of kebaya.[23] However, some conservative Islamic clerics have condemned the movement as a "veiled apostasy", aimed to demote the use of hijab among Indonesian Muslim women.[24] Indeed, some suggests that the kebaya-wearing movement is actually a counter-action against the increasingly conservatism and Arabization within Indonesian society, that warily saw the increase of niqāb-wearing among local women.[25]

Gallery

-

European child with sarong and kebaya, early 20th century

-

European woman in sarong and kebaya, early 20th century

-

Silver kebaya kerongsang pin, the Tropenmuseum collection (c. 1927)

-

Indonesian movie star Chitra Dewi in kebaya (c. 1960)

-

Kebaya as national costume representing Indonesia in beauty pageant (2012)

![]() Media related to Kebaya at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kebaya at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Media related to Tropenmuseum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tropenmuseum at Wikimedia Commons

See also

- National costume of Indonesia

- Culture of Indonesia

- Culture of Malaysia

- Culture of Singapore

- Javanese culture

- Htaingmathein

References

- ^ a b "Arti kata kebaya - Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia (KBBI) Online". kbbi.web.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ a b "Women promote 'kebaya' wearing at MRT station". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ a b Jill Forshee, Culture and customs of Indonesia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 0-313-33339-4, 237 pages

- ^ "The Kebaya - An Indonesian Traditional Dress for Women". www.expat.or.id. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ Denys Lombard (1990). Le carrefour javanais: essai d'histoire globale. Civilisations et sociétés (in French). École des hautes études en sciences sociales. ISBN 2-7132-0949-8.

- ^ a b c Triyanto (29 December 2010). "Kebaya Sebagai Trend Busana Wanita Indonesia dari Masa ke Masa" (PDF) (in Indonesian).

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Times, I. D. N.; Khalika, Nindias. "Sejarah Kebaya, Pakaian Perempuan Sejak Abad ke-16". IDN Times (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ a b Maenmas Chavalit, Maneepin Phromsuthirak: Costumes in ASEAN: ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information: 2000: ISBN 974-7102-83-8, 293 pages

- ^ S. A. Niessen, Ann Marie Leshkowich, Carla Jones: Re-orienting Fashion: the globalization of Asian dress Berg Publishers: 2003: ISBN 978-1-85973-539-8, pp. 206-207

- ^ Cattoni Reading The Kebaya; paper was presented to the 15th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia in Canberra 29 June-2 July 2004.

- ^ Michael Hitchcock Indonesian Textiles: HarperCollins, 1991

- ^ "Sejarah Kebaya di Masa Kolonial: Busana Perempuan Tiga Etnis". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ Panular, P. B. R. Carey, The British in Java, 1811-1816: a Javanese account : a text edition, English synopsis and commentary on British Library Additional Manuscript 12330 (Babad Bĕdhah ing Ngayogyakarta), British Academy by Oxford University Press: 1992, ISBN 0-19-726062-4, 611 pages

- ^ John Pemberton, On the subject of "Java", Cornell University Press: 1994, ISBN 0-8014-9963-1, 333 pages

- ^ Inger McCabe Elliott Batik: Fabled Cloth of Java, Hong Kong: Periplus, 2004

- ^ Mattiebelle Gittinger, To Speak with Cloth: studies in Indonesian textiles University of California, 1989

- ^ a b c d Widiyarti, Yayuk (2019-07-17). "Aneka Jenis Kebaya Indonesia, Mana yang Paling Anda Suka?". Tempo (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ a b c d "Mengenal Jenis-Jenis Kebaya di Indonesia". Go Socio (in Indonesian).

- ^ a b Adriani Zulivan (4 March 2017). "Benarkah Kebaya adalah Pakaian Asli Indonesia?". Good News From Indonesia (in Indonesian).

- ^ Agnes Swetta Pandia & Nina Susilo (13 January 2013). "Tantangan Bisnis Kebaya Encim" (in Indonesian). Female Kompas.com. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ Cattoni Reading The Kebaya paper was presented to the 15th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia in Canberra 29 June-2 July 2004: 8

- ^ Kompas Female Terbang Bersama Kebaya

- ^ Post, The Jakarta. "#SelasaBerkebaya movement aims to promote 'kebaya' as daily outfit". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ "Saat Gerakan Berkebaya Dituduh Agenda Permurtadan Terselubung" (in Indonesian). Tirto.id. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Latumahina, Jeannie (2018-04-04). "Puisi Sukmawati Gerakan Keadilan budaya". Media Kritis Anak Bangsa (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2019-10-10.