Sopwith Triplane

| Sopwith Triplane | |

|---|---|

| |

| Triplane reproduction G-BOCK at Old Warden, 2013 | |

| Role | Fighter |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Sopwith Aviation Company |

| Designer | Herbert Smith |

| First flight | 28 May 1916 |

| Introduction | December 1916 |

| Primary user | Royal Naval Air Service |

| Number built | 147[1][2] |

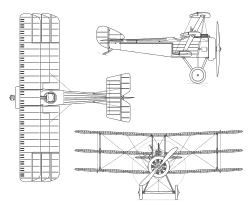

The Sopwith Triplane was a British single seat fighter aircraft designed and manufactured by the Sopwith Aviation Company during the First World War. It has the distinction of being the first military triplane to see operational service.

The Triplane was developed by the firm's experimental department as a private venture, the project was headed by the designer Herbert Smith. Aside from its obvious difference in wing configuration, the aircraft shared many similarities with the company's successful biplane fighter, the Sopwith Pup. The prototype Triplane performed its maiden flight on 28 May 1916 and was dispatched to the French theatre two months later, where it garnered high praise for its exceptional rate of climb and high manoeuvrability. During late 1916, quantity production of the type commenced in response to orders received from the Admiralty. During early 1917, production examples of the Triplane arrived with Royal Naval Air Service squadrons.

The Triplane rapidly proved to be capable of outstanding agility, and thus was quickly deemed to be a success amongst those squadrons that flew it.[citation needed] Praise for the type extended to opposing pilots; Imperial Germany extensively studied the Triplane via captured examples and produced numerous tri-winged aircraft shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, the Triplane was built in comparatively small numbers to that of the more conventional Sopwith Pup. It had been decided to withdraw the Triplane from active service as increasing numbers of the Sopwith Camel arrived in the latter half of 1917. Surviving Triplanes continued to serve as operational trainers and experimental aircraft until months following the end of the conflict.

Development

Background

During the First World War, the Sopwith Aviation Company became a prominent British manufacturer of military aircraft.[3] It was amid this conflict that one of its employees, Herbert Smith, designed the Sopwith Pup, a single-seat biplane fighter aircraft which was described by aviation author J.M. Bruce as being "one of the world's greatest aeroplanes".[3] While it was a capable fighter that possessed impressive handling qualities for its era, from an aerodynamic perspective, the Pup was an entirely conventional design. Certain figures, including those within Sopwith's experimental department, sought to develop a successor which would instead pioneer new concepts for such an aircraft; out of such ambitions would emerge the Triplane.[3]

Early on, Sopwith decided to pursue development of the Triplane concept as a private venture initiative.[3] The design, which was passed by the company's experimental department on 28 May 1916, was contemporary to the Sopwith L.R.T.Tr. project, which never progressed beyond the prototype stage; Bruce speculated that Smith may have been inspired by the L.R.T.Tr.'s atypical wing configuration to adopt the iconic triplane configuration for the new project.[3] Beyond the obvious difference in terms of wing configuration, the Triplane's design largely conformed with that of the Pup. It has been described as being a "remarkably simple aircraft".[3]

Into flight

The initial "prototype of what was to be referred to simply as the Triplane" first flew on 28 May 1916, with Sopwith test pilot Harry Hawker at the controls.[4] Within three minutes of takeoff, Hawker startled onlookers by looping the aircraft, serial N500, three times in succession.[5] Hawker noted that this was due to his high confidence in the aircraft despite its radical design.[3] The Triplane was very agile, with effective, well-harmonised controls.[6] When maneuvering, however, the Triplane presented an unusual appearance. One observer noted that the aircraft looked like "a drunken flight of steps" when rolling.[7]

While initially lacking any armament, N500 was subsequently furnished with a single Vickers machine gun, which was mounted centrally in front of the cockpit.[3] In July 1916, N500 was sent to Dunkirk for evaluation with "A" Naval Squadron, 1 Naval Wing. Being put into action within 15 minutes of its arrival to intercept enemy aircraft, N500 quickly proved to be highly successful. According to Bruce, it demonstrated exemplary maneuverability and a phenomenal rate of climb for the era.[3]

The second prototype, N504, performed its maiden flight in August 1916. Its primary difference from the first prototype was the installation of a 130 hp Clerget 9B engine.[8] N504 was eventually dispatched to France in December of that year.[9] This aircraft served as a conversion trainer for several squadrons.[9]

Production

Between July 1916 and January 1917, the Admiralty issued two contracts to Sopwith for a total of 95 Triplanes, two contracts to Clayton & Shuttleworth Ltd. for a total of 46 aircraft, and one contract to Oakley & Co. Ltd. for 25 aircraft.[10] Seeking modern aircraft for the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), the War Office also issued a contract to Clayton & Shuttleworth for 106 Triplanes.[11][12]

Quantity production of the type commenced in late 1916. The first Sopwith-built Triplanes were delivered to Clayton & Shuttleworth, who delivered their first Triplane on 2 December 1916.[13] A renewed urgency amongst the Allied Powers for high performance combat aircraft came following the emergence of the Albatros D.II, which entered service with Imperial Germany around this same time frame, which threatened Allied aerial supremacy.[8] In February 1917, the War Office agreed to exchange its Triplane orders for the Admiralty's SPAD S.VII contracts.[11][14][15]

While both Sopwith and Clayton & Shuttleworth successfully fulfilled their RNAS production orders,[10] Oakley, which had no prior experience building aircraft, delivered only three Triplanes before its contract was cancelled during October 1917.[16][17] For unknown reasons, the RFC Triplane contract issued to Clayton & Shuttleworth was simply cancelled rather than being transferred to the RNAS.[11] Total production of the type amounted to 147 aircraft.[1][14]

Design

The Sopwith Triplane was a single seat fighter aircraft; it shared a considerable amount of its design features, such as its fuselage and empennage, with those of the earlier Pup. While the fuselage was structurally similar, Bruce notes that there were several areas of differences present.[3] One example was the attachment points present for the center wings, which were carried upon the top and bottom longerons of the fuselage and in turn also attached to the center-section struts. One innovation that was present only on the Triplane was the use of single broad-chord interplane struts, which ran continuously between the lower and upper wings.[3]

The most distinctive feature of the Triplane is its three narrow-chord wings; these provided the pilot with an improved field of view. These wings had the exact same span as that of the Pup, while being only 21 square feet less in terms of area.[3] Ailerons were fitted to all three wings. The relatively narrow chord and short span wings have been attributed with providing a high level of manoeuvrability.[3] The introduction of a smaller 8 ft span tailplane in February 1917 was attributed with improved elevator response.[18] The original tail assembly was identical to the Pup's, other than the inclusion of the variable incidence tailplane, which could be adjusted so that the aircraft could be flown hands-off.[19][3]

The Triplane was initially powered by the 110 hp Clerget 9Z nine-cylinder rotary engine. However, the majority of production examples were instead fitted with the more powerful 130 hp Clerget 9B rotary. At least one Triplane was tested with a 110 hp Le Rhône rotary engine, but this did not provide a significant improvement in performance, the only seeming benefit being a slight increase in its rate of climb.[13]

Operational history

Introduction

No. 1 Naval Squadron became fully operational with the Triplane by December 1916, but the squadron did not see any significant action until February 1917, when it relocated from Furnes to Chipilly.[20] No. 8 Naval Squadron received its Triplanes in February 1917.[21][13] Nos. 9 and 10 Naval Squadrons equipped with the type between April and May 1917.[22]

All but one British Triplane were dispatched to squadrons based in France; this sole aircraft was instead sent to the Aegean, although its service details and purpose there is largely unknown, only that its use was curtailed after a crash-landing in Salonika on 26 March 1917.[23] Aside from the British, the only other major operator of the Triplane was a French naval squadron based at Dunkirk, which received 17 aircraft.[24][25] A single example was shipped to the United States for exhibition purposes in December 1917. Furthermore, the Imperial Russian Air Service also operated a single Triplane during the latter half of 1917, its fate being unknown.[26]

The Triplane's combat debut was highly successful. The new fighter's exceptional rate of climb and high service ceiling gave it a marked advantage over the Albatros D.III, though the Triplane was slower in a dive.[27] During April 1917, Manfred von Richthofen, better known as The Red Baron, commented that the Triplane was the best Allied fighter at that time, a sentiment that was echoed by other German senior officers such as Ernst von Hoeppner.[28] Multiple Triplanes were captured and subject to considerable evaluation and study.[29] The Germans were so impressed by the aircraft's performance that it spawned a brief triplane craze among German aircraft manufacturers. Their efforts resulted in no fewer than 34 different prototypes, including the Fokker V.4, prototype of the successful Fokker Dr.I.[30]

Pilots nicknamed the aircraft the Tripehound or simply the Tripe.[31] The Triplane was famously flown by "B" Flight 10 Naval Squadron, better known as "Black Flight". This all-Canadian flight was commanded by the ace Raymond Collishaw. Their aircraft, named Black Maria, Black Prince, Black George, Black Death and Black Sheep, were distinguishable by their black-painted fins and cowlings.[7] Black Flight claimed 87 German aircraft in three months while equipped with the Triplane. Collishaw scored 34 of his eventual 60 victories in the aircraft, making him the top Triplane ace.[32][33]

Issues

The Triplane's combat career was comparatively brief, in part because it proved difficult to repair.[28] The fuel and oil tanks were inaccessible without dismantling the wings and fuselage; even relatively minor repairs had to be made at rear echelon repair depots. Spare parts became difficult to obtain during the summer of 1917, resulting in the reduction of No. 1 Naval Squadron's complement from 18 to 15 aircraft.[34] According to Bruce, it is plausible that squadrons were slow to refit their Triplanes with the improved tailplane due to a lack of available kits for doing so.[35]

The Triplane also gained a reputation for structural weakness because the wings of some aircraft collapsed in steep dives. This defect was attributed to the use of light gauge bracing wires in the 46 aircraft built by subcontractor Clayton & Shuttleworth.[36] Several pilots of No. 10 Naval Squadron used cables or additional wires to strengthen their Triplanes.[36] Bruce alleges that there was no substance to the concerns of structural weakness.[8] In 1918, the RAF issued a technical order for the installation of a spanwise compression strut between the inboard cabane struts of surviving Triplanes. One aircraft, serial N5912, was fitted with additional mid-bay flying wires on the upper wing while used as a trainer.

Another drawback of the Triplane was its light armament.[37] Contemporary Albatros fighters were armed with two guns but most Triplanes carried one synchronised Vickers machine gun. Efforts to fit twin guns to the Triplane met with mixed results. Clayton & Shuttleworth built six experimental Triplanes with twin guns.[14] Some of these aircraft saw combat service with Nos. 1 and 10 Naval Squadrons in July 1917 but performance was reduced and the single gun remained standard.[38] Triplanes built by Oakley would have featured twin guns, an engineering change which severely delayed production.[17]

Withdrawal from service

In June 1917, No. 4 Naval Squadron received the first Sopwith Camels and the advantages of the sturdier, better-armed fighter quickly became evident. Nos. 8 and 9 Naval Squadrons re-equipped with Camels between early July and early August 1917.[39] No. 10 Naval Squadron converted in late August, turning over its remaining Triplanes to No. 1 Naval Squadron.[36] No. 1 operated Triplanes until December, allegedly suffering heavy casualties as a consequence of the slow replacement of their Triplanes.[40]

By the end of 1917, surviving Triplanes were used as advanced trainers with No. 12 Naval Squadron. For a time, the type remained in use for experimental and training purposes; examples were recorded as performing flights as late as October 1918.[41] Six British aces scored all of their victories on Sopwith Triplanes. These were John Albert Page (7), Thomas Culling (6), Cyril Askew Eyre (6), F. H. Maynard (6), Gerald Ewart Nash (6) and Anthony Arnold (5). [42]

Operators

- Aéronautique navale (17 aircraft)

- Hellenic Navy (one aircraft)

- Imperial Russian Air Force (one aircraft)

- Soviet Air Force (one aircraft taken over from the Imperial Russian Air Force)

Survivors and modern reproductions

- Canada

- Reproduction – On static display at The Hangar Flight Museum in Calgary, Alberta. This aircraft represents serial N6302, flown by Alfred Williams Carter of No. 10 Naval Squadron.[43]

- Reproduction – In storage at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario.[44]

- Russia

- N5486 – On static display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino, Moscow. It was supplied to the Russian Government for evaluation in May 1917. In Russia, the aircraft was fitted with skis and used operationally until captured by the Bolshevists. The aircraft then served in the Red Air Force, probably as a trainer, and was rebuilt many times.[45]

- United States

- Reproduction – On static display at the MAPS Air Museum in North Canton, Ohio.[46] It was built by Akron pilot Bill Woodall using original Sopwith plans.[47]

- United Kingdom

- N5912 – On static display at the Royal Air Force Museum London in London. It was one of three aircraft built by Oakley & Co. Ltd. and delivered in late 1917. The aircraft saw no combat service and instead served with No.2 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery at Marske. After the war, the Imperial War Museum displayed the aircraft in a temporary exhibition until 1924. In 1936, the Royal Air Force acquired and restored the aircraft, flying it in several RAF Pageants at Hendon.[48][49]

- Reproduction – Airworthy at the Shuttleworth Collection in Old Warden, Bedfordshire. This aircraft is registered as G-BOCK and is marked as Dixie II. It represents the original Dixie, serial N6290, of No. 8 Naval Squadron.[50][51][52]

- Reproduction – Airworthy as part of the Great War Display Team. This aircraft is registered as N500, the first Triplane prototype which flew with No. 1 Squadron RNAS) from 1916.[53]

Specifications (Clerget 9B-engined variant)

Data from British Aeroplanes 1914–18[54] Aircraft Profile No. 73: The Sopwith Triplane[55]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 18 ft 10 in (5.74 m)

- Wingspan: 26 ft 6 in (8.08 m)

- Height: 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m)

- Wing area: 231 sq ft (21.5 m2)

- Empty weight: 1,101 lb (499 kg)

- Gross weight: 1,541 lb (699 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Clerget 9B 9-cylinder air-cooled rotary piston engine, 130 hp (97 kW)

- Propellers: 2-bladed fixed-pitch propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 117 mph (188 km/h, 102 kn) at 5,000 ft (1,524 m)

- Range: 321 mi (517 km, 279 nmi)

- Endurance: 2 hours 45 minutes

- Service ceiling: 20,500 ft (6,200 m)

- Time to altitude:

- 6,000 ft (1,829 m) in 5 minutes 50 seconds

- 16,400 ft (4,999 m) in 26 minutes 30 seconds

- Wing loading: 6.13 lb/sq ft (29.9 kg/m2)

Armament

- Guns: 1× .303 in (7.70 mm) Vickers machine gun

See also

Related development

- Alcock Scout

- St Croix Sopwith Triplane, a homebuilt replica design

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

Notes

- ^ a b Bowers and McDowell 1993, p. 63.

- ^ Bruce 1965, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bruce 1965, p. 3.

- ^ Green and Swanborough 2001, p. 534.

- ^ Robertson 1970, p. 59.

- ^ Franks 2004, p. 19.

- ^ a b Connors 1975, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Bruce 1965, p. 4.

- ^ a b Franks 2004, p. 50.

- ^ a b Davis 1999, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Davis 1999, p. 72.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 3-4.

- ^ a b c Bruce 1965, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Mason 1992, p. 61.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 4-5.

- ^ Davis 1999, p. 76.

- ^ a b Robertson 1970, p. 157.

- ^ Cooksley 1991, p. 23.

- ^ Franks 2004, pp. 19, 66.

- ^ Franks 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Franks 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Franks 2004, pp. 54, 68.

- ^ Bruce 1965, p. 8.

- ^ Franks 2004, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Bruce 1965, p. 9.

- ^ Franks 2004, pp. 21, 69.

- ^ a b Bruce 1965, p. 7.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 7-8.

- ^ Kennett 1991, p. 98,

- ^ Bowers and McDowell 1993, p. 62.

- ^ Franks 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Lamberton 1960, p. 74.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 5-6.

- ^ a b c Franks 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Franks 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Franks 2004, pp. 13, 69.

- ^ Franks 2004, pp. 46, 49, 56–57.

- ^ Franks 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Bruce 1965, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Davis 1999, p. 75.

- ^ "SOPWITH TRIPLANE". The Hangar Flight Museum. The Hangar Flight Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Sopwith Triplane". Ingenium. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Bruce 1990, p. 19.

- ^ "SOPWITH TRIPLANE "TRIPEHOUND"". MAPS Air Museum. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Woodall, Bill. "Building and Flying". Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Sopwith Triplane". Royal Air Force Museum. Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Simpson, Andrew (2013). "INDIVIDUAL HISTORY [N5912]" (PDF). Royal Air Force Museum. Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Hiscock 1994, p. 30.

- ^ "SOPWITH TRIPLANE". Shuttleworth. Shuttleworth. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "GINFO Search Results [G-BOCK]". Civil Aviation Authority. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "The Team Aircraft". Great War Display Team. Great War Display Team. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Bruce 1957, p. 568.

- ^ Bruce 1965, p. 12.

Bibliography

- Bowers, Peter M. and Ernest R. McDowell. Triplanes: A Pictorial History of the World's Triplanes and Multiplanes. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1993. ISBN 0-87938-614-2.

- Bruce, J.M. British Aeroplanes 1914–18. London:Putnam, 1957.

- Bruce, J. M. "Aircraft Profile No. 73: The Sopwith Triplane". Profile Publications Ltd, 1965.

- Bruce, J.M. Sopwith Triplane (Windsock Datafile 22). Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Productions, 1990. ISBN 0-948414-26-X.

- Connors, John F. "Sopwith's Flying Staircase." Wings, Volume 5, No. 3, June 1975.

- Cooksley, Peter. Sopwith Fighters in Action (Aircraft No. 110). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1991. ISBN 0-89747-256-X.

- Davis, Mick. Sopwith Aircraft. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire: Crowood Press, 1999. ISBN 1-86126-217-5.

- Franks, Norman. Sopwith Triplane Aces of World War I (Aircraft of the Aces No. 62). Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-728-X.

- Green, William, and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. Osceola, Wisconsin: MBI Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Hiscock, Melvyn. Classic Aircraft of World War I (Osprey Classic Aircraft). Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1994. ISBN 1-85532-407-5.

- Kennett, Lee. The First Air War: 1914–1918. New York: The Free Press, 1991. ISBN 0-02-917301-9.

- Lamberton, W.M., and E.F. Cheesman. Fighter Aircraft of the 1914–1918 War. Letchworth: Harleyford, 1960. ISBN 0-8168-6360-1.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Fighter Since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55750-082-7.

- Robertson, Bruce. Sopwith – The Man and His Aircraft. London: Harleyford, 1970. ISBN 0-900435-15-1.

- Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft Since 1912. London: Putnam, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

External links

- The Sopwith Triplane – Great Britain, Aviation history.

- Canada Aviation Museum: Sopwith Triplane

- "The Sopwith Triplane" a 1918 Flight re-print of a German article on the Triplane originally published in Deutsche Luftfahrer Zeitschrift.