Batik

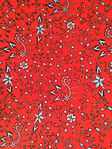

Batik from Surakarta in Central Java province in Indonesia; before 1997 | |

| Type | Art Fabric |

|---|---|

| Material | Cambrics, silk, cotton |

| Place of origin | Indonesia |

| Batik | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Domains | Traditional craftsmanship,Oral traditions and expressions, Social practices, rituals and festive events |

| Reference | 170 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2009 (4th session) |

| List | Representative |

Batik[n 1] is an Indonesian technique of wax-resist dyeing applied to whole cloth. This technique originated from the island of Java, Indonesia.[1] Batik is made either by drawing dots and lines of the resist with a spouted tool called a canting,[n 2] or by printing the resist with a copper stamp called a cap.[n 3][2] The applied wax resists dyes and therefore allows the artisan to colour selectively by soaking the cloth in one colour, removing the wax with boiling water, and repeating if multiple colours are desired.[1]

Batik is an ancient art form made with wax resistant dye on fabrics; the batik of Indonesia may be the best-known.[3][4] Indonesian batik made in the island of Java has a long history of acculturation, with diverse patterns influenced by a variety of cultures, and is the most developed in terms of pattern, technique, and the quality of workmanship.[5]

In October 2009, UNESCO designated Indonesian batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[6]

Etymology

The word batik is Javanese in origin. It comes from the Javanese word amba ('to write') and titik ('dot'). Batik in Sundanese is Euyeuk, cloth can be processed into a form of Batik by a Pangeyeuk (Batik maker), written in the contents of the Manuscript Sanghyang Siksa Kandang Karesian which was written in 1518 AD.[7] The word is Batik first recorded in English in the Encyclopædia Britannica of 1880, in which it is spelled battik. It is attested in the Indonesian Archipelago during the Dutch colonial period in various forms: mbatek, mbatik, batek and batik.[8][9][10]

story

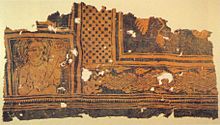

Wax resist dyeing of fabric is an ancient art form. It already existed in Egypt in the 4th century BC, where it was used to wrap mummies;[11] linen was soaked in wax, and scratched using a stylus. In Asia, the technique was practised in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), and in Japan during the Nara Period (645–794 AD). In Africa, it was originally practised by the Yoruba tribe in Nigeria, Soninke and Wolof in Senegal.[12] This African version however, uses cassava starch or rice paste, or mud as a resist instead of beeswax.[13]

The art of batik is most highly developed in the island of Java in Indonesia. In Java, all the materials for the process are readily available – cotton and beeswax and plants from which different vegetable dyes are made.[14] Indonesian batik predates written records: G. P. Rouffaer argues that the technique might have been introduced during the 6th or 7th century from India or Sri Lanka.[12] On the other hand, the Dutch archaeologist J.L.A. Brandes and the Indonesian archaeologist F.A. Sutjipto believe Indonesian batik is a native tradition, since several regions in Indonesia such as Toraja, Flores, and Halmahera which were not directly influenced by Hinduism, have attested batik making tradition as well.[15]

Based on the contents of the Sundanese Manuscript, Sundanese people have known about Batik since the 12th century. Based on ancient Sundanese manuscript Sanghyang Siksa Kandang Karesian writen 1518 ad it is recorded that Sundanese having batik which is identical and representative of Sundanese culture in general. Several motif are even noted in the text, based on those data sources the process of Batik Sundanese creation begins step by step.[16]

Rouffaer reported that the gringsing pattern was already known by the 12th century in Kediri, East Java. He concluded that this delicate pattern could be created only by using the canting, an etching tool that holds a small reservoir of hot wax, and proposed that the canting was invented in Java around that time.[15] The carving details of clothes worn by East Javanese Prajnaparamita statues from around the 13th century show intricate floral patterns within rounded margins, similar to today's traditional Javanese jlamprang or ceplok batik motif.[17] The motif is thought to represent the lotus, a sacred flower in Hindu-Buddhist beliefs. This evidence suggests that intricate batik fabric patterns applied with the canting existed in 13th-century Java or even earlier.[18] By the last quarter of the 13th century, the batik cloth from Java has been exported to Karimata islands, Siam, even as far as Mosul.[19]

In Europe, the technique was described for the first time in the History of Java, published in London in 1817 by Stamford Raffles, who had been a British governor for Bengkulu, Sumatra. In 1873 the Dutch merchant Van Rijckevorsel gave the pieces he collected during a trip to Indonesia to the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam. Today the Tropenmuseum houses the biggest collection of Indonesian batik in the Netherlands. The Dutch and Chinese colonists were active in developing batik, particularly coastal batik, in the late colonial era. They introduced new patterns as well as the use of the cap (copper block stamps) to mass-produce batiks. Displayed at the Exposition Universelle at Paris in 1900, the Indonesian batik impressed the public and artists.[12]

In the 1920s, Javanese batik makers migrating to Malaya (now Malaysia) introduced the use of wax and copper blocks to its east coast.[20]

In Subsaharan Africa, Javanese batik was introduced in the 19th century by Dutch and English traders. The local people there adapted the Javanese batik, making larger motifs with thicker lines and more colours. In the 1970s, batik was introduced to Australia, where aboriginal artists at Erna Bella have developed it as their own craft.[21]

- Some ancient Indonesian statues that use batik motifs

-

Kawung batik motif on the Mahakala statue clothes, Gatekeeper at the Shiva residence on Mount Kailash, from a temple complex at Singhasari, Malang, East Java, Indonesia, 1275-1300. Collection: Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, Netherland

-

Kawung batik motif on Nandishvara statue clothes (foreground, 13th century) from the collection of the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, Netherland

Technique

Firstly, a cloth is washed, soaked and beaten with a large mallet. Patterns are drawn with pencil and later redrawn using hot wax, usually made from a mixture of paraffin or beeswax, sometimes mixed with plant resins, which functions as a dye-resist. The wax can be applied with a variety of tools. A pen-like instrument called a canting (Template:IPA-jv, sometimes spelled with old Dutch orthography tjanting) is the most common. A tjanting is made from a small copper reservoir with a spout on a wooden handle. The reservoir holds the resist which flows through the spout, creating dots and lines as it moves. For larger patterns, a stiff brush may be used.[22] Alternatively, a copper block stamp called a cap (Template:IPA-jv; old spelling tjap) is used to cover large areas more efficiently.[23]

After the cloth is dry, the resist is removed by boiling or scraping the cloth. The areas treated with resist keep their original colour; when the resist is removed the contrast between the dyed and undyed areas forms the pattern.[24] This process is repeated as many times as the number of colours desired.

The most traditional type of batik, called batik tulis (written batik), is drawn using only the canting. The cloth needs to be drawn on both sides, and dipped in a dye bath three to four times. The whole process may take up to a year; it yields considerably finer patterns than stamped batik.[5]

Culture

Many Indonesian batik patterns are symbolic. Infants are carried in batik slings decorated with symbols designed to bring the child luck, and certain batik designs are reserved for brides and bridegrooms, as well as their families.[25] During the colonial era, Javanese courts issued decrees that dictated certain patterns to be worn according to a person's rank and class within the society. Sultan Hamengkubuwono VII, who ruled the Yogyakarta Sultanate from 1921 to 1939, reserved several patterns such as the Parang Rusak and Semen Agung for members of the Yogyakartan royalties and restricted commoners from wearing them.[26] Batik garments play a central role in certain Javanese rituals, such as the ceremonial casting of royal batik into a volcano. In the Javanese naloni mitoni ceremony, the mother-to-be is wrapped in seven layers of batik, wishing her good things. Batik is also prominent in the tedak siten ceremony when a child touches the earth for the first time.[27] Contemporary practice often allows people to pick any batik patterns according to one's taste and preference from casual to formal situations, and Batik makers often modify, combine, or invent new iterations of well known patterns. Specific pattern requirement are often reserved for traditional and ceremonial contexts.[28]

In October 2009, UNESCO designated Indonesian batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. As part of the acknowledgment, UNESCO insisted that Indonesia preserve its heritage.[25] The day, 2 October 2009 has been stated by Indonesian government as National Batik Day,[29] as also at the time the map of Indonesian batik diversity by Hokky Situngkir was opened for public for the first time by the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Technology.[30]

Study of the geometry of Indonesian batik has shown the applicability of fractal geometry in traditional designs.[31]

Popularity

The popularity of batik in Indonesia has varied. Historically, it was essential for ceremonial costumes and it was worn as part of a kebaya dress, commonly worn every day. The use of batik was already recorded in the 12th century, and the textile has become a strong source of identity for Indonesians crossing religious, racial and cultural boundaries. It is also believed the motif made the batik famous.[32]

| Cultural Influence | Batik Pattern | Geographic Location | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Indonesian | kawung, ceplok, gringsing, parang, lereng, truntum, sekar jagad (combination of various motifs) and other decorative motifs of Java, Dayak, Batak, Papua, Riau, etc. | Respective areas |

|

| Hindu-Buddhist | garuda, banji, cuwiri, kalpataru, meru or gunungan, semen rama, pringgondani, sidha asih, sidha mukti, sidha luhur | Java |

|

| Islamic | besurek or Arabic calligraphy, buraq | Bengkulu, Cirebon, Jambi |

|

| Chinese | burung hong (Chinese phoenix), liong/naga (Chinese dragon), qilin, wadasan, megamendung (Chinese-style cloud), lok tjan | Lasem [id], Cirebon, Pekalongan, Tasikmalaya, Ciamis |

|

| Indian | jlamprang, peacock, elephant | Cirebon, Garut, Pekalongan, Madura |

|

| European (colonial era) | buketan (floral bouquet), European fairytale, colonial images such as house, horses, carriage, bicycle and European-dressed people | Java |

|

| Japanese | sakura, hokokai, chrysanthemum, butterfly | Java |

|

The batik industry of Java flourished from the late 1800s to early 1900s, but declined during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia.[5] With increasing preference of western clothing, the batik industry further declined following the Indonesian independence. Batik has somewhat revived at the turn of the 21st century, through the efforts of Indonesian fashion designers to innovate batik by incorporating new colours, fabrics, and patterns. Batik has become a fashion item for many Indonesians, and may be seen on shirts, dresses, or scarves for casual wear; it is a preferred replacement for jacket-and-tie at certain receptions. Traditional batik sarongs are still used in many occasions.[33]

After the UNESCO recognition for Indonesian batik on 2 October 2009, the Indonesian administration asked Indonesians to wear batik on Fridays, and wearing batik every Friday has been encouraged in government offices and private companies ever since.[34] 2 October is also celebrated as National Batik Day in Indonesia.[34] Batik had helped improve the small business local economy, batik sales in Indonesia had reached Rp 3.9 trillion (US$436.8 million) in 2010, an increase from Rp 2.5 trillion in 2006. The value of batik exports, meanwhile, increased from $14.3 million in 2006 to $22.3 million in 2010.[35]

Batik is also popular in the neighbouring countries of Singapore and Malaysia. It is produced in Malaysia with similar, but not identical, methods to those used in Indonesia. Prior to UNESCO's recognition and following the 2009 Pendet controversy, Indonesia and Malaysia disputed the ownership of batik culture. However, Dr Fiona Kerlogue of the Horniman museum argued that the Malaysian printed wax textiles, made for about a century, were quite a different tradition from the "very fine" traditional Indonesian batiks produced for many centuries.[36]

Batik is featured in the national airline uniforms of the three countries, represented by batik prints worn by flight attendants of Singapore Airlines, Garuda Indonesia and Malaysian Airlines. The female uniform of Garuda Indonesia flight attendants is a modern interpretation of the Kartini style kebaya with parang gondosuli motifs.[37][38]

Terminology

Batik is traditionally sold in 2.25-metre lengths used for kain panjang or sarong. It is worn by wrapping it around the hip, or made into a hat known as blangkon. The cloth can be filled continuously with a single pattern or divided into several sections.

Certain patterns are only used in certain sections of the cloth. For example, a row of isosceles triangles, forming the pasung motif, as well as diagonal floral motifs called dhlorong, are commonly used for the head. However, pasung and dhlorong are occasionally found in the body. Other motifs such as buketan (flower bouquet) and birds are commonly used in either the head or the body.[5]

- The head is a rectangular section of the cloth which is worn at the front. The head section can be at the middle of the cloth, or placed at one or both ends. The papan inside of the head can be used to determine whether the cloth is kain panjang or sarong.[5]

- The body is the main part of the cloth, and is filled with a wide variety of patterns. The body can be divided into two alternating patterns and colours called pagi-sore ('dawn-dusk'). Brighter pattern are shown during the day, while darker pattern are shown in the evening. The alternating colours give the impression of two batik sets.[5]

- Margins are often plain, but floral and lace-like patterns, as well as wavy lines described as a dragon, are common in the area beside seret.[5]

Types

As each region has its own traditional pattern, batiks are commonly distinguished by the region they originated in, such as batik Solo, batik Yogyakarta, batik Pekalongan, and batik Madura. Batiks from Java can be distinguished by their general pattern and colours into batik pedalaman (inland batik) or batik pesisir (coastal batik). Batiks which do not fall neatly into one of these two categories are only referred to by their region. A mapping of batik designs from all places in Indonesia depicts the similarities and reflects cultural assimilation within batik designs.[39]

Javanese Batik

Inland Batik

Inland batik or batik kraton (Javanese court batik) is the oldest form of batik tradition known in Java. Inland batik has earthy colour[40] such as black, indigo, brown, and sogan (brown-yellow colour made from the tree Peltophorum pterocarpum), sometimes against a white background, with symbolic patterns that are mostly free from outside influence. Certain patterns are worn and preserved by the royal courts, while others are worn on specific occasions. At a Javanese wedding for example, the bride wears specific patterns at each stage of the ceremony.[41] Noted inland batiks are produced in Solo and Jogjakarta, cities traditionally regarded as the centre of Javanese culture. Batik Solo typically has sogan background and is preserved by the Susuhunan and Mangkunegaran Court. Batik Jogja typically has white background and is preserved by the Yogyakarta Sultanate and Pakualaman Court.[27]

Coastal Batik

Coastal batik is produced in several areas of northern Java and Madura. In contrast to inland batik, coastal batiks have vibrant colours and patterns inspired by a wide range of cultures as a consequence of maritime trading.[40] Recurring motifs include European flower bouquets, Chinese phoenix, and Persian peacocks.[25] Noted coastal batiks are produced in Pekalongan, Cirebon, Lasem, Tuban, and Madura. Pekalongan has the most active batik industry.[5]

A notable sub-type of coastal batik called Jawa Hokokai[42] is not attributed to a particular region. During the Japanese occupation of Indonesia in early 1940, the batik industry greatly declined due to material shortages. The workshops funded by the Japanese however were able to produce extremely fine batiks called Jawa Hokokai.[5] Common motifs of Hokokai includes Japanese cherry blossoms, butterflies, and chrysanthemums.

Another coastal batik called tiga negeri (batik of three lands) is attributed to three regions: Lasem, Pekalongan, and Solo, where the batik would be dipped in red, blue, and sogan dyes respectively. As of 1980, batik tiga negeri was only produced in one city.[5]

Sundanese Batik

Sundanese or Parahyangan Batik is the term for batik from the Parahyangan region of West Java and Banten.[43] Although Parahyangan batiks can use a wide range of colours, a preference for indigo is seen in some of its variants. Natural indigo dye made from Indigofera is among the oldest known dyes in Java, and its local name tarum has lent its name to the Citarum river and the Tarumanagara kingdom, which suggests that ancient West Java was once a major producer of natural indigo. Noted Parahyangan batik is produced in Ciamis, Garut, and Tasikmalaya. Other traditions include Batik Kuningan influenced by batik Cirebon, batik Banten that developed quite independently, and an older tradition of batik Baduy.

Batik Banten employs bright pastel colours and represents a revival of a lost art from the Sultanate of Banten, rediscovered through archaeological work during 2002–2004. Twelve motifs from locations such as Surosowan and several other places have been identified.[44]

Batik Baduy only employs indigo colour in shades ranged from bluish black to deep blue. It is traditionally worn as iket, a type of Sundanese headress similar to Balinese udeng, by Outer Baduy people of Lebak Regency, Banten.[45]

Sumatran Batik

Trade relations between the Melayu Kingdom in Jambi and Javanese coastal cities have thrived since the 13th century. Therefore, coastal batik from northern Java probably influenced Jambi. In 1875, Haji Mahibat from Central Java revived the declining batik industry in Jambi. The village of Mudung Laut in Pelayangan district is known for producing batik Jambi. Batik Jambi, as well as Javanese batik, influenced the Malaysian batik.[46]

The Minangkabau people also produce batik called batiak tanah liek (clay batik), which use clay as dye for the fabric. The fabric is immersed in clay for more than 1 day and later designed with motifs of animal and flora.[47] The Batik from Bengkulu, a city on west coast of Sumatra, is called Batik Besurek, which literary means "batik with letters" as they draw inspiration from Arabic calligraphy.

Balinese Batik

Batik making in the island of Bali is relatively new, but a fast-growing industry. Many patterns are inspired by local designs, which are favoured by the local Balinese and domestic tourists.[48] Objects from nature such as frangipani and hibiscus flowers, birds or fishes, and daily activities such as Balinese dancer and ngaben processions or religious and mythological creatures such as barong, kala and winged lion are common. Modern batik artists express themselves freely in a wide range of subjects.[49]

Contemporary batik is not limited to traditional or ritual wearing in Bali. Some designers promote batik Bali as elegant fabric that can be used to make casual or formal cloth. Using high class batik, like hand made batik tulis, can show social status.[49]

Batik outside Indonesia

Malaysia

The origin of batik production in Malaysia it is known trade relations between the Melayu Kingdom in Jambi and Javanese coastal cities have thrived since the 13th century, the northern coastal batik producing areas of Java (Cirebon, Lasem, Tuban, and Madura) has influenced Jambi batik. This Jambi (Sumatran) batik, as well as Javanese batik, has influenced the batik craft in the Malay peninsula.[50]

The method of Malaysian batik making is different from those of Indonesian Javanese batik, the pattern being larger and simpler with only occasional use of the canting to create intricate patterns. It relies heavily on brush painting to apply colours to fabrics. The colours also tend to be lighter and more vibrant than deep coloured Javanese batik. The most popular motifs are leaves and flowers. Malaysian batik often displays plants and flowers to avoid the interpretation of human and animal images as idolatry, in accordance with local Islamic doctrine.[51] However, the butterfly theme is a common exception.

India

Indians are known to use resist method of printing designs on cotton fabrics, which can be traced back 2000 years. Initially, wax and even rice starch were used for printing on fabrics. Until recently batik was made only for dresses and tailored garments, but modern batik is applied in numerous items, such as murals, wall hangings, paintings, household linen, and scarves, with livelier and brighter patterns.[24] Contemporary batik making in India is also done by the Deaf women of Delhi, these women are fluent in Indian Sign Language and also work in other vocational programs.[52]

Sri Lanka

Over the past century, batik making in Sri Lanka has become firmly established. The Sri Lankan batik industry is a small scale industry which can employ individual design talent and mainly deals with foreign customers for profit. It is now the most visible of the island's crafts with galleries and factories, large and small, having sprung up in many tourist areas. Rows of small stalls selling batiks can be found all along Hikkaduwa's Galle Road strip. Mahawewa, on the other hand, is famous for its batik factories.[53][54]

China

Batik is done by the ethnic people in the South-West of China. The Miao, Bouyei and Gejia people use a dye resist method for their traditional costumes. The traditional costumes are made up of decorative fabrics, which they achieve by pattern weaving and wax resist. Almost all the Miao decorate hemp and cotton by applying hot wax then dipping the cloth in an indigo dye. The cloth is then used for skirts, panels on jackets, aprons and baby carriers. Like the Javanese, their traditional patterns also contain symbolism, the patterns include the dragon, phoenix, and flowers.[55]

Africa

Although modern history would suggest that the Batik was introduced to Africa by the Dutch, the batik making process has been practiced in Africa long before the arrival of the colonial powers. One of the earlier sightings are to be found in Egypt, where batik was used in the embalming of mummies. The most developed resist-dyeing skills are to be found in Nigeria where the Yoruba make adire cloths. Two methods of resist are used: adire eleso which involves tied and stitched designs and adire eleko that uses starch paste. The paste is most often made from cassava starch, rice, and other ingredients boiled together to produce a smooth thick paste. The Yoruba of West Africa use cassava paste as a resist while the Soninke and Wolof people in Senegal uses rice paste. The Bamana people of Mali use mud as a resist.[13] Batik was worn as a symbol of status, ethnic origin, marriage, cultural events, etc.

African wax prints (Dutch wax prints) was introduced during the colonial era, through Dutch's textile industry's effort to imitate the batik making process. The imitation wasn't successful in Europe, but experienced a strong reception in Africa instead.[56][57]: 20 Today batik is produced in many parts of Africa and it is worn by many Africans as a symbol of culture.

Nelson Mandela is a noted wearer of batik during his lifetime. Mandela regularly wore patterned loose-fitting shirt to many business and political meetings during (1994–99) and after his tenure as President of South Africa, subsequently dubbed as a Madiba shirt based on Mandela's Xhosa clan name.[58] There are many who claim the Madiba shirt's invention. Yusuf Surtee, a clothing-store owner who supplied Mandela with outfits for decades, said the Madiba design is based on Mandela's request for a shirt similar to Indonesian president Suharto's batik attire.[59]

Gallery

Indonesian batik

- Some of batik motifs and patterns

-

Gajah oling batik motif from Banyuwangi, East Java.

-

Sidhomukti batik motif and pattern From Solo, Central Java.

-

Sidha drajat pattern from Solo, Central Java.

-

Typical inland batik (batik pedalaman) from Yogyakarta.

-

Typical bright red colour in batik Lasem called abang getih pithik (chicken blood red) From Rembang, Central Java.

-

Sarong from northern Java, circa 1900s.

-

Pasung or pucuk rebung pattern of batik.

-

Coastal batik (batik pesisiran) with buketan motif from Pekalongan, Central Java.

Batik making process

- Batik making

-

Initial pattern drawn with a pencil.

-

Various tools for making batik, canting is shown in the top.

-

Drawing patterns with wax using canting.

-

Printing wax-resin resist for Batik with a cap.

-

Applying wax using cap (copper plate stamps).

-

A cap for applying hot wax.

-

Selection of cap copper printing blocks with traditional batik patterns.

-

Dyeing the cloth in colour.

-

Dyeing the cloth in colour.

People wearing batik

- Batik

-

Pakubuwono X in kain batik.

-

Bedhaya dancers from Solo wearing batik.

-

Servants in Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat wearing batik.

-

A group of women wearing colourful batiks.

-

A Javanese man wearing typical contemporary batik shirt.

-

Portrait of a woman in sarong and kebaya with child.

-

Nelson Mandela wearing batik.

See also

Notes

- ^ Javanese: ꦧꦛꦶꦏ꧀, Template:IPA-jv; Template:IPA-id

- ^ Javanese: ꦕꦤ꧀ꦛꦶꦁ, Template:IPA-jv, also spelled tjanting

- ^ Javanese: ꦕꦥ꧀, Template:IPA-jv, also spelled tjap

References

- ^ a b "What is Batik?". The Batik Guild.

- ^ The Jakarta Post Life team. "Batik: a cultural dilemma of infatuation and appreciation". The Jakarta Post.

- ^ Robert Pore (12 February 2017). "A unique style, Hastings artist captures wonder of crane migration". The Independent.

- ^ Sucheta Rawal (4 October 2016). "The Many Faces of Sustainable Tourism – My Week in Bali". Huffingtonpost.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sumarsono, Hartono; Ishwara, Helen; Yahya, L.R. Supriyapto; Moeis, Xenia (2013). Benang Raja: Menyimpul Keelokan Batik Pesisir. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9106-01-8.

- ^ "Indonesian Batik". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Ekajati, Edi Suhardi (2005). Kebudayaan Sunda: Zaman Pajajaran (in Indonesian). Pustaka Jaya. ISBN 978-979-419-334-1.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: Batik

- ^ Dictionary.com: Batik

- ^ Blust, Robert (Winter 1989). "Austronesian Etymologies – IV". Oceanic Linguistics. 28 (2): 111–180. doi:10.2307/3623057. JSTOR 3623057.

- ^ "Egyptian Mummies". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Nadia Nava, Il batik – Ulissedizioni – 1991 ISBN 88-414-1016-7

- ^ a b "Batik in Africa". The Batik Guild. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Batik in Java". The Batik Guild. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ a b Iwan Tirta, Gareth L. Steen, Deborah M. Urso, Mario Alisjahbana, 'Batik: a play of lights and shades, Volume 1', By Gaya Favorit Press, 1996 ISBN 979-515-313-7 ISBN 978-979-515-313-9

- ^ M.Ds, Irma Russanti, S. Pd. History of The Development of Kebaya Sunda. Pantera Publishing. ISBN 978-623-91996-0-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Keunikan Makna Filosofi Batik Klasik: Motif Jlamprang" (in Indonesian). Fit in line. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Prajnaparamita and other Buddhist deities". Volkenkunde Rijksmuseum. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Jung-pang, Lo (2013). China as a Sea Power, 1127-1368. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc. ISBN 9789971697136.

- ^ Museum of Cultural History, Oslo: Malaysia – Batikktradisjoner i bevegelse. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ Antropolog Australia Beri Ceramah Soal Batik. Retrieved 29 April 2014. (in Indonesian)

- ^ Trefois, Rita (2010). Fascinating Batik. ISBN 978-90-815246-2-9

- ^ Batik Nomination for inscription on the Representative List in 2009 (Reference No. 00170)

- ^ a b Charan (28 September 2011). "Indian batik: Another Ancient Art of Printing on Textiles". Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b c UNESCO – Intangible Heritage Section. "UNESCO Culture Sector – Intangible Heritage – 2003 Convention". unesco.org.

- ^ "Batik: The Forbidden Designs of Java – Australian Museum". australia.nmuseum.

- ^ a b "Batik Days". The Jakarta Post. 2 October 2009.

- ^ "Batik patterns hold deep significance". thejakartapost.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Ingat, Besok Hari Batik Nasional, Wajib Pakai Batik". setkab.go.id. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ "Mengupas Center for Complexity Surya University". Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Situngkir, Hokky; Dahlan, Rolan; Surya, Yohanes. Fisika batik : implementasi kreatif melalui sifat fraktal pada batik secara komputasional. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama (2009). ISBN 9789792244847 & ISBN 9792244840

- ^ "Book Review – Batik: Creating an Identity". WhyGo Indonesia. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Nomination for inscription on the Representative List in 2009 (Reference No. 00170)". UNESCO. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Administration calls for all-in batik day this Friday". thejakartapost.com.

- ^ "Let's use batik as diplomatic tool: SBY". thejakartapost.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011.

- ^ Indonesians tell Malaysians 'Hands off our batik' Telegraph.co.uk, accessed 8 October 2009

- ^ Indriasari, Lusiana; Yulia Sapthiani (26 September 2010). "Terbang Bersama Kebaya" (in Indonesian). Female Kompas.com. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Pujobroto, PT (2 June 2010). "Garuda Indonesia Launches New Uniform". Garuda Indonesia.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Hokky Situngkir (2 February 2009). "Phylomemetic Tree of Indonesian Traditional Batik". Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ a b Reichle, Natasha (2012). "Batik: Spectacular Textiles of Java" The Newsletter. International Institute for Asian Studies

- ^ Nunuk Pulandari (13 April 2011). "Arti dan Cerita di balik Motif Batik Klasik Jawa". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2014. (in Indonesian)

- ^ Note: Jawa Hokokai (ジャワ奉公会) was a Japanese-led organization of locals for war-cooperation.

- ^ Pradito, Didit; Jusuf, Herman; Atik, Saftyaningsih Ken (2010). The Dancing Peacock: Colours and Motifs of Priangan Batik. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 978-979-22-5825-7. Page 5

- ^ Uke Kurniawan, Memopulerkan Batik Banten, haki.lipi.go.id, accessed 4 October 2009

- ^ "Batik Baduy diminati pengunjung Jakarta Fair" (in Indonesian). Antara News.com. 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ National Geographic Traveller Indonesia, Vol 1, No 6, 2009, Jakarta, Indonesia, page 54

- ^ "Pesona Batik Jambi" (in Indonesian). Padang Ekspres. 16 November 2008. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Bali Batik, Bali Sarong, Kimono - Bali Textiles, Bali Garment, Clothing - balibatiku.com". balibatiku.com.

- ^ National Geographic Traveller Indonesia, Vol 1, No 6, 2009, Jakarta, Indonesia, page 54

- ^ "Figural Representation in Islamic Art". metmuseum.org.

- ^ Burch, Susan; Kaferq, Alison (2010). Deaf and Disability Studies. Washington D.C: GU Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-56368-464-7.

- ^ "Sri Lankan Batik Textiles". Lakpura Travels. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Kannangara, Ananda (10 June 2012). "Brighter future for batik industry". Sunday Observer (Sri Lanka). Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Batik in China Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Batik Guild, 1999

- ^ Kroese, W.T. (1976). The origin of the Wax Block Prints on the Coast of West Africa. Hengelo: Smit. ISBN 9062895018.

- ^ LaGamma, Alisa (2009). The Essential Art of African Textiles: Design Without End. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Grant & Nodoba 2009, p. 361.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 103.

Sources

- Doellah, H.Santosa. (2003). Batik : The Impact of Time and Environment, Solo : Danar Hadi. ISBN 979-97173-1-0

- Elliott, Inger McCabe. (1984) Batik : fabled cloth of Java photographs, Brian Brake ; contributions, Paramita Abdurachman, Susan Blum, Iwan Tirta ; design, Kiyoshi Kanai. New York : Clarkson N. Potter Inc., ISBN 0-517-55155-1

- Fraser-Lu, Sylvia.(1986) Indonesian batik : processes, patterns, and places Singapore : Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-582661-2

- Gillow, John; Dawson, Barry. (1995) Traditional Indonesian Textiles. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27820-2

- Grant, Terri; Nodoba, Gaontebale (August 2009), "Dress Codes in Post-Apartheid South African Workplaces", Business Communication Quarterly, 72 (3): 360–365, doi:10.1177/1080569909340683, S2CID 167453202

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - QuaChee & eM.K. (2005) Batik Inspirations: Featuring Top Batik Designers. ISBN 981-05-4447-2

- Raffles, Sir Thomas Stamford. (1817) History of Java, Black, Parbury & Allen, London.

- Smith, Daniel (2014), How to Think Like Mandela, Michael O'Mara, ISBN 9781782432401

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sumarsono, Hartono; Ishwara, Helen; Yahya, L.R. Supriyapto; Moeis, Xenia (2013). Benang Raja: Menyimpul Keelokan Batik Pesisir. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9106-01-8.

- Tirta, Iwan; Steen, Gareth L.; Urso, Deborah M.; Alisjahbana, Mario. (1996) "Batik: a play of lights and shades, Volume 1", Indonesia : Gaya Favorit. ISBN 979-515-313-7, ISBN 978-979-515-313-9

- Nadia Nava, Il batik – Ulissedizioni – 1991 ISBN 88-414-1016-7

External links

- UNESCO: Indonesian Batik, Representative of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity – 2009

- Video tutorial about African batik

- Early Indonesian textiles from three island cultures: Sumba, Toraja, Lampung, exhibition catalogue from Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Batik, the Traditional Fabric of Indonesia an article about batik from Living in Indonesia

- iWareBatik | Indonesian Batik Textile Heritage A website devoted to Batik, Indonesian Textile enlisted by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage. It links Batik production with Tourism and Fashion in Indonesia