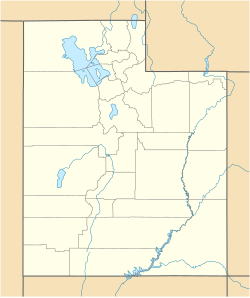

Kimberly, Utah

Kimberly | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 38°29′N 112°23′W / 38.483°N 112.383°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Utah |

| County | Piute |

| Established | 1890s |

| Abandoned | 1938 |

| Named for | Peter Kimberly |

| Elevation | 8,970 ft (2,734 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1446867[1] |

Kimberly is a ghost town in the northwest corner of Piute County, Utah, United States. Located high in Mill Canyon on the side of Gold Mountain in the Tushar Mountains, Kimberly was formerly a gold mining town. Originally settled in the 1890s, it lasted until 1910. Kimberly had a minor rebirth in the 1930s, but has been uninhabited since approximately 1938. The town is perhaps best known as the birthplace of Ivy Baker Priest, a former United States Treasurer.

History

Foundation

Prospectors began to strike gold in the Gold Mountain area as early as 1888. Newton Hill located the famous Annie Laurie mines here in 1891, and Willard Snyder developed the Bald Mountain Mine. Snyder platted out a Mill Canyon townsite, which he named Snyder City. A few businesses sprang up in town, but the real growth began in 1899 when Sharon, Pennsylvania investor Peter L. Kimberly bought the Annie Laurie and other area mines. Kimberly incorporated his holdings as the Annie Laurie Consolidated Gold Mining Company,[3] which established a gold cyanidation mill here.[4]

Growth

The town, renamed Kimberly, began to boom. Mill Canyon's terrain naturally divided Kimberly into two sections: Upper Kimberly, the residential area higher up the canyon, and Lower Kimberly, the business district that had been Snyder City. Lower Kimberly's main street bent around the head of the canyon in a horseshoe shape.[3] Kimberly quickly became the leading gold camp in the state, with two hotels, two stores, three saloons, and two newspapers.[5] In 1900 the county formed the Gold Mountain School District, and a log schoolhouse was built. Enrollment peaked at 89 in 1903. Kimberly's school year was just the opposite of the North American norm: children attended school from April through November to avoid the deep snows of winter.[3]

The boom period of 1901–1908 is considered to be the town's heyday;[4] the Annie Laurie Company absorbed several other mines and paid out nearly $500,000 in dividends during this time.[3] By 1902 the Annie Laurie employed 300 miners,[5] and Kimberly's population reached 500.[3] The steep canyon road was constantly filled with wagons carrying ore, bullion, and supplies to and from the railroad station at the town of Sevier. The heavy traffic kept the road passable through the winter.[4] It was during this period that Ivy Baker Priest was born in 1905, in a house at the north end of Lower Kimberly. She later became United States Treasurer under President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[3]

Like most mining camps, Kimberly was known as a wild and vice-ridden place. Its brothels were famous, and drunkenness was commonplace. The town had problems with violence, even murder.[4] The two-cell jail was said to be the strongest within 100 miles (160 km).[3]

Decline

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 104 | — | |

| 1910 | 8 | −92.3% | |

| 1920 | 3 | −62.5% |

Kimberly reached a turning point with the death of Peter Kimberly, in 1905. The Annie Laurie Company was sold to a British company that lacked experience running a mining operation. The new owners tried to cut labor costs using the truck system, paying workers in scrip redeemable only at the company store. Miners began resigning in disgust. The company borrowed heavily to build a new processing mill, and was caught in a vulnerable position by the Panic of 1907. The Annie Laurie Consolidated Gold Mining Company declared bankruptcy in 1910, closing the mines and the town. Combined company assets, for which Peter Kimberly had refused an offer of $5,000,000 in 1902, sold at auction for $31,000. The 1910 United States Census recorded Kimberly's population as 8.[3]

For years only a few men remained at Kimberly, doing minor maintenance.[4] Then in 1931 a new vein of ore was opened up and a smaller mill built. The company hired some 50 men to work the mine, and Kimberly was revived.[3] The new body of gold and silver ore was mined out by 1938; Kimberly was re-abandoned. Most of the salvageable buildings were moved away by 1942.[4] Both Piute County and the Gold Hill Mining Company claimed ownership of the old jailhouse;[3] after staying at Kimberly for many years it was moved to Pioneer Village, now at Lagoon Amusement Park in northern Utah.[5]

Kimberly's high elevation makes it inaccessible for much of the year, but many remnants of the town are still visible. The upper part of the canyon is filled with tailings. Ruins of many log and frame buildings line the lower canyon, the skeleton of the Annie Laurie mill is still standing, and a few mine buildings are largely intact.[4]

References

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Upper Kimberly

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lower Kimberly

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Newell, Linda King (January 1999). A History of Piute County (PDF). Utah Centennial County History Series. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah State Historical Society. pp. 179–185. ISBN 0-913738-39-5. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carr, Stephen L. (June 1986) [1972]. The Historical Guide to Utah Ghost Towns (3rd ed.). Salt Lake City: Western Epics. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-914740-30-X.

- ^ a b c Thompson, George A. (November 1982). Some Dreams Die: Utah's Ghost Towns and Lost Treasures. Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-942688-01-5.

Further reading

- Pace, Josephine (Spring 1967). "Kimberly as I Remember her" (PDF). Utah Historical Quarterly. 35 (2): 112–120. ISSN 0042-143X. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

External links

- Kimberly at GhostTowns.com