Amnesty International

Amnesty International (commonly known as Amnesty or AI) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) comprising "a worldwide movement of people who campaign for internationally recognized human rights".[1] Essentially it compares actual practices of human rights with internationally accepted standards and demands compliance where these have not been respected. It works to mobilize public opinion in the belief that it is this which has the power to exert pressure on those who perpetrate abuses.

Rationale

The rationale of Amnesty International is formed from several key ideas. It argues that:

- Human rights are unalienable and universal. They are natural laws which are the birthright of all human beings. Everyone is entitled without distinction.

- Human rights are indivisible. Violating rights to protect other rights or in the name of “higher” causes undermines the principle of universality. There is no conflict between rights, they share common bounds. When rights are deprived others are threatened, when secured others can follow.

- Human rights will not be protected by governments alone. Governments have declared their commitment to human rights and have bound themselves by covenants, yet violations persist throughout the world. There are many pressures on governments to disregard human rights and it is at this point of failure that human rights organizations have a role to play.

- Defense of human rights requires individuals to act on behalf of others. The violation of one individual’s rights can set in motion a pattern of further abuses. The place to stop patterns of abuse emerging is at the level of the individual. Moreover, it is at this level that the action of the ordinary individual can make a difference.

- Independence and impartiality are necessary in the defense of human rights. It is not appropriate to support or oppose any particular political, economic or religious ideology. Neither is it appropriate to single out any country or regime, or method of violation as the “worst”. The focus is on the individual and all individuals.

Early history: 1961-1979 and origins

On December 10, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the 30 articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). At the same time governmental representatives, who made up the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, ruled that it had no power to interfere in the internal affairs of governments in order to act on specific human rights complaints. As a result, a situation developed in which “practical measures to give life to human rights principles began to lag far behind the rhetoric”.[2] Twelve years on, in November 1960, two Portuguese students, Ivone Lourenço and another student friend, were sentenced to seven years imprisonment for a remark made which was critical of the Portuguese government (see Salazar dictatorship).

Amnesty International was conceived by English lawyer and recent Catholic convert Peter Benenson when, traveling to work one morning, he read of the plight of these two students in the news. Benenson also traced the idea back to the Spanish Civil War, and he was aware of existing activism in the area, notably the communist-backed 'Appeal for Amnesty in Spain'. Benenson, in consultation with other writers, academics and lawyers, particularly the Quaker peace activist Eric Baker, wrote via Louis Blom-Cooper to David Astor, editor of The Observer newspaper, who, on May 28, 1961, published Benenson's article The Forgotten Prisoners. The article brought the reader’s attention to those “imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government” [3] or, put another way, to violations, by governments, of articles 18 and 19 of the UDHR. The article described these violations occurring, on a global scale, in the context of restrictions to press freedom, to political oppositions, to timely public trial before impartial courts, and to asylum. It also launched 'Appeal for Amnesty, 1961', the aim of which was to mobilize public opinion, quickly and widely, in defence of these individuals who Benenson named "Prisoners of Conscience". In the same year Benenson had a book published, persecution 1961, which detailed the cases of several prisoners of conscience investigated and compiled by Benenson and Baker.[4]

What started as a short appeal soon became a permanent international movement, ‘Amnesty International’, working to protect those imprisoned for non-violent expression of their views and to secure worldwide recognition of Articles 18 and 19 of the UDHR. From the very beginning, research and campaigning were present in Amnesty International’s work. A library was established for information about prisoners of conscience and a network of local groups, called ‘THREES’ groups, was started. Each group worked on behalf of three prisoners, one from each of the then three main ideological regions of the world: communist, capitalist and developing.

By the mid-1960s Amnesty International’s global presence was growing and an International Secretariat and International Executive Committee was established to manage Amnesty International’s national organizations, called ‘Sections’, which had appeared in several countries. The international movement was starting to agree its core principles and techniques. For example, the issue of whether or not to adopt prisoners who had advocated violence, like Nelson Mandela, brought unanimous agreement that it could not give the name of ‘Prisoner of Conscience’ to such prisoners. Aside from the work of the library and groups, Amnesty International’s activities were expanding to helping prisoner’s families, sending observers to trials, making representations to governments, and finding asylum or overseas employment for prisoners. Its activity and influence was also increasing within intergovernmental organizations; it would be awarded consultative status by the United Nations, the Council of Europe and UNESCO before the decade was out.

Leading Amnesty International in the 1970s were key figureheads Sean MacBride and Martin Ennals. While continuing to work for prisoners of conscience, Amnesty International’s purview widened to include “fair trial” and opposition to long detention without trial (UDHR Article 9), and especially to the torture of prisoners (UDHR Article 5). Amnesty International believed that the reasons underlying torture of prisoners, by governments, were either to obtain information or to quell opposition by the use of terror, or both. Also of concern was the export of more sophisticated torture methods, equipment and teaching to “client states”.

Amnesty International drew together reports from countries where torture allegations seemed most persistent and organized an international conference on torture. It sought to influence public opinion in order to put pressure on national governments by organizing a campaign for the ‘Abolition of Torture’ which ran for several years.

Amnesty International’s membership increased from 15,000 in 1969[5] to 200,000 by 1979.[6] This growth in resources enabled an expansion of its program, ‘outside of the prison walls’, to include work on “disappearances”, the death penalty and the rights of refugees. A new technique, the ‘Urgent Action’, aimed at mobilizing the membership into action rapidly was pioneered. The first was issued on March 19, 1973, on behalf of Luiz Basilio Rossi, a Brazilian academic, arrested for political reasons.

At the intergovernmental level Amnesty International pressed for application of the UN’s Standard Minimum Prison Rules and of existing humanitarian conventions; to secure ratifications of the two UN Covenants on Human Rights (which came into force in 1976); and was instrumental in obtaining UN Resolution 3059 which formally denounced torture and called on governments to adhere to existing international instruments and provisions forbidding its practice. Consultative status was granted at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1972.

Recent history: 1980-2005

By 1980, Amnesty International, now a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and a UN Human Rights Prize winner, was drawing more criticism from governments. The USSR was alleging that Amnesty International conducted espionage, the Moroccan government denounced it as a defender of lawbreakers, and in Argentina, Amnesty International’s 1983 annual report was banned. Such hostility made defending human rights a dangerous occupation in some countries.

Throughout the 80s, Amnesty International continued to campaign for prisoners of conscience and of torture, and on the other issues added to its mandate over the years. Again new issues emerged including: extrajudicial killings; military, security and police transfers; political killings; and “disappearances” (especially under military dictatorships in Latin America).

Towards the end of the decade the growing numbers, worldwide, of refugees was a very visible area of Amnesty International’s concern. While many of the world’s refugees of the time had been displaced by war and famine, in adherence to its mandate, Amnesty International concentrated on those forced to flee because of the human rights violations it was seeking to prevent. It argued that rather than focusing on new restrictions on entry for asylum-seekers, governments ought to address the human rights violations which were forcing people into exile.

Apart from a second campaign on torture during the first half of the decade, the major campaign of the 80s was the ‘Human Rights Now!’ tour which featured many of the famous musicians and bands of the day playing concerts to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the UDHR.

Throughout the 1990s Amnesty International, now with a membership of one million[7] led by Senegalese Secretary General Pierre Sané, worked on a wide range of issues and world events.

Amnesty International was forced to react to human rights violations occurring in the context of a proliferation of armed conflict in: Angola, East Timor, the Persian Gulf, Rwanda, Somalia and the former Yugoslavia. Amnesty International took no position on whether to support or oppose external military interventions in these armed conflicts. It did not (and does not) reject the use of force, even lethal force, or ask those engaged to lay down their arms. Rather it questioned the motives behind external intervention and selectivity of international action in relation to the strategic interests of those sending troops. It argued that action should be taken in time to prevent human rights problems becoming human rights catastrophes and that both intervention and inaction represented a failure of the international community.

However, Amnesty International was proactive in pushing for recognition of the universality of human rights. The campaign ‘Get Up, Sign Up’ marked 50 years of the UDHR. Thirteen million pledges were collected in support of the Declaration and a music concert was held in Paris on December 10, 1998 (Human Rights Day).

In particular, Amnesty International brought attention to violations committed on specific groups including: refugees, racial/ethnic/religious minorities, women and those executed or on death row. The death penalty report When the state kills and the ‘Human Rights are Women's Rights’ campaign were key actions for the latter two issues and demonstrate that Amnesty International was still very much a reporting and campaigning organization.

At the intergovernmental level, Amnesty International argued in favor of creating a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (established 1993) and an International Criminal Court (established 2002).

Post 2000, Amnesty International’s agenda turned to the challenges arising from globalization and the effects of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the US. The issue of globalization provoked a major shift in Amnesty International policy, as the scope of its work was widened to include economic, social and cultural rights, an area that it had declined to work on in the past. Amnesty International felt this shift was important, not just to give credence to its principle of the indivisibility of rights, but because of the growing power of companies and the undermining of many nation states as a result of globalization.

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the new Amnesty International Secretary General, Irene Khan, reported that a senior government official had said to Amnesty International delegates: "Your role collapsed with the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York".[8] In the years following the attacks, some of the gains made by human rights organizations over previous decades were eroded. Amnesty International argued that human rights were the basis for the security of all, not a barrier to it. Criticism came directly from the Bush administration and The Washington Post, when Khan, in 2005, likened the US government’s detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to a Soviet Gulag. [9] [10]

During the first half of the new decade Amnesty International turned its attention to violence against women, controls on the world arms trade and concerns surrounding the effectiveness of the UN. Its membership, close to two million by 2005[11], continued to work for prisoners of conscience.

Work

Amnesty International’s vision is of a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards.

In pursuit of this vision, Amnesty International’s mission is to undertake research and action focused on preventing and ending grave abuses of the rights to physical and mental integrity, freedom of conscience and expression, and freedom from discrimination, within the context of its work to promote all human rights.— Statute of Amnesty International, 27th International Council meeting, 2005

This mission translates into specific aims which are to:

- Abolish the death penalty

- End extrajudicial executions and "disappearances"

- Ensure prison conditions meet international human rights standards

- Ensure prompt and fair trial for all political prisoners

- Fight impunity from systems of justice

- End the recruitment and use of child soldiers

- Free all prisoners of conscience

- Promote economic, social and cultural rights for marginalized communities

- Protect human rights defenders

- Stop torture and ill-treatment

- Stop unlawful killings in armed conflict

- Uphold the rights of refugees, migrants and asylum seekers

Amnesty International targets not only governments, but also non governmental bodies and private individuals (non state actors).

To further these aims Amnesty International has developed several techniques to publicize information and mobilize public opinion. The organization considers as one of its strengths the publication of impartial and accurate reports. Reports are researched by interviewing victims and officials, observing trials, working with local human rights activists and by monitoring the media. It aims to issue timely press releases and publishes information in newsletters and on web sites. It also sends official missions to countries to make courteous but insistent inquiries.

Campaigns to mobilize public opinion can take the form of individual, country or thematic campaigns. Many techniques are deployed such as direct appeals (for example, letter writing), media and publicity work and public demonstrations. Often fundraising is integrated with campaigning.

In situations which require immediate attention, Amnesty International calls on existing urgent action networks or crisis response networks; for all other matters it calls on its membership. It considers the large size of its human resources to be another one of its key strengths.

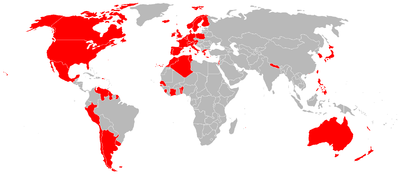

Organization

Amnesty International is largely made up of voluntary members but retains a small number of paid professionals. Its organization is intended to reflect its principles of international solidarity and democracy. Members are organized according to various models depending on the strength of presence in a particular country. The movement is most established in the West, less so in the global South and East. In countries where Amnesty International has a strong presence, members are organized as ‘Sections’. Sections coordinate basic Amnesty International activities normally with a significant volume of members (some of whom will form into ‘Groups’) and a professional staff, each have a board of directors. In 2005, worldwide, there were 52 Sections. ‘Structures’ are aspiring Sections, they too coordinate basic activities but have a smaller membership and a limited staff. In countries where no Section or Structure exists people can become ‘International Members’. Two other organizational models exist: ‘International Networks’, which promote specific themes or have a specific identity; and ‘Affiliated Groups’, which do the same work as Section Groups, but in isolation.

The organizations outlined above are represented by the International Council (IC) which is led by the IC Chairperson. Members of Sections and Structures have the right to appoint, one or more, representatives to the Council according to the size of their membership. The IC may invite representatives from International Networks and other individuals to meetings, but only representatives from Sections and Structures have voting rights. The function of the IC is to appoint and hold accountable internal governing bodies and to determine the direction of the movement. The IC convenes every two years.

The International Executive Committee (IEC), led by the IEC Chairperson, consists of eight members and the IEC Treasurer. It is elected by, and represents, the IC and meets biannually. The role of the IEC is to take decisions on behalf of Amnesty International, implement the strategy laid out by the IC, and ensure compliance with the movement’s statutes.

The International Secretariat (IS) is responsible for the conduct and daily affairs of Amnesty International under direction from the IEC and IC. It is run by approximately 500 professional staff and is headed by the Secretary General. The IS operates several work programs: International Law and Organizations; Research; Campaigns; Mobilization; and Communications. Its offices have been located in London since its establishment in the mid-1960s.

Amnesty International is financed largely by fees and donations from its worldwide membership. It does not accept donations from governments or governmental organizations.

Amnesty International Sections, 2005

Algeria; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Belgium (Flemish speaking); Belgium (French speaking); Benin; Bermuda; Canada (English speaking); Canada (French speaking); Chile; Côte d’Ivoire; Denmark; Faroe Islands; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Guyana; Hong Kong; Iceland; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Japan; Korea (Republic of); Luxembourg; Mauritius; Mexico; Morocco; Nepal; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Peru; Philippines; Poland; Portugal; Puerto Rico; Senegal; Sierra Leone; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Taiwan; Togo; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States of America; Uruguay; Venezuela.

Amnesty International Structures, 2005

Belarus; Bolivia; Burkina Faso; Croatia; Curaçao; Czech Republic; Gambia; Hungary; Malaysia; Mali; Moldova; Mongolia; Pakistan; Paraguay; Slovakia; South Africa; Thailand; Turkey; Ukraine; Zambia; Zimbabwe.

IEC Chairpersons

Seán MacBride, 1965–1974; Dirk Börner, 1974–1977; Thomas Hammarberg, 1977–1979; José Zalaquett, 1979–1982; Suriya Wickremasinghe, 1982–1985; Stephen R. Abrams, 1985–1991; Ligia Bolivar, 1991–1993; Ross Daniels, 1993–1997; Colm O Cuanachain, 1998–2003; Jaap Jacobson, 2003–2005; Hanna Roberts, 2005–2006; Lilian Gonçalves-Ho Kang You, 2006–present.

Secretaries General

Peter Benenson, 1961–1966 (President); Eric Baker, 1966–1968; Martin Ennals, 1968–1980; Thomas Hammarberg, 1980–1986; Ian Martin, 1986–1992; Pierre Sané, 1992–2001; Irene Khan, 2001–present.

Criticism and response

Since its establishment in the early 1960s Amnesty International has occasionally been criticized. Criticisms often appear in the media in the form of quotes from government officials, and commentaries by journalists and bloggers. Criticisms have centred mainly around its reporting and alleged bias. From time to time Amnesty International publishes a selection of criticisms of itself including public statements, press reports and cartoons. Outlined below are some of main criticisms directed at Amnesty International and the organization's response.

Criticism: Amnesty International has been criticized for being biased in the selectivity of its coverage of human rights violations. Allegations have been levelled that there are a disproportionate number of reports on relatively more democratic and open countries which are lesser violators of human rights. This has been called "Moynihan's Law" after the late US Senator and former Ambassador to the United Nations, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who is said to have commented that, the number of complaints about a nation's violation of human rights is inversely proportional to their actual violation of human rights.

Amnesty International's response: Its intention is not to produce a range of reports which give greater coverage to the "worst" violators. Instead, its aim is to document what it can, in order to produce pressure for improvement. This skews the number of reports towards more open and democratic countries because information is more easily obtainable.

Criticism: Amnesty International has been accused of being politically biased. Governments have criticized not only the contents of its reporting but have complained that the timing of publication has often aided their political opponents.

Amnesty International's response: If it is political, it is not because it is partisan but because it addresses and makes demands of those in power. Amnesty International claims to address all governments openly and disseminate its information as widely as possible. In addition, it states that it attaches paramount importance to accuracy, but that it is prepared to correct any errors it has made. Before publishing major country reports it asks the governments concerned for its comments and has often abstained from immediate publication in order to give those in authority an opportunity to clarify the facts.[12]

Criticism: Amnesty International has been accused of being ideologically biased.

Amnesty International's response: Perceived ideological bias is a misconception, Amnesty International does not work for or against governments, but against human rights violations. In addition, it does not reserve its criticisms for just governments but also reports on non state actors including: opposition groups, economic actors and armed groups.[13]

Criticism: Amnesty International has been accused of being provocative.

Amnesty International's response: If it is perceived as provocative, it is not because it seeks to offend, but because it exposes abuses which contradict official versions of events.[14]

Criticism: Amnesty International has been criticized for interfering in the internal affairs of state.

Amnesty International's response: Human rights are an international responsibility and a matter of legitimate international concern. Governments are accountable not only to their own people but also to the international community. Governments have a duty to cooperate with international organizations, to admit international observers to their political trials and/or prisons, and to respond to complaints raised at the United Nations.[15]

Footnotes

- ^ [Amnesty International Report 2006]: the state of the world's human rights (foreword). Amnesty International. 2005.

- ^ Clark, Ann Marie (2001). Diplomacy of conscience: Amnesty International and changing human rights norms. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Benenson, Peter (1961-05-28). "The forgotten prisoners". The Observer. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Buchanan, T. (2002) 'The Truth Will Set You Free': The Making of Amnesty International. Journal of Contemporary History 37(4) pp. 575-597

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1968-69. Amnesty International. 1969.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1979. Amnesty International. 1980.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1990. Amnesty International. 1991.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 2002. Amnesty International. 2003.

- ^ "'American Gulag'". The Wahington Post. 2005-05-26. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Bush says Amnesty report 'absurd'". BBC. 2005-05-31. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Amnesty International Report 2005: the state of the world's human rights. Amnesty International. 2004.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1983. Amnesty International. 1982.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1983. Amnesty International. 1982.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1983. Amnesty International. 1982.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1983. Amnesty International. 1982.

Further reading

- Hopgood, Stephen (2006). Keepers of the Flame: Understanding Amnesty International. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4402-0.

- Amnesty International (2005). Amnesty International Report 2006: The State of the World's Human Rights. Amnesty International. ISBN 0-86210-369-X.

- Clarke, Anne Marie (2001). Diplomacy of Conscience: Amnesty International and Changing Human Rights Norms. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05743-5.

- Power, Jonathan (1981). Amnesty International: The Human Rights Story. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-08-028902-9.

External links

International website

Section websites (English language)

- Amnesty International Australia website

- Amnesty International Canada website

- Amnesty International Ireland website

- Amnesty International New Zealand website

- Amnesty International UK website

- Amnesty International USA website

Section websites (Other languages)

Campaign websites

Other websites

- United Nations Human Rights website

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights website

- Nobel website

- Human Rights Watch website

- ARTICLE 19 website

- US Human Rights Network website