2 Kings 20

| 2 Kings 20 | |

|---|---|

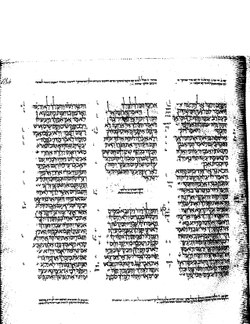

The pages containing the Books of Kings (1 & 2 Kings) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Second Book of Kings |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 4 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 12 |

2 Kings 20 is the twentieth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1][2] The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE.[3] This chapter records the events during the reign of Hezekiah and Manasseh, the kings of Judah.[4][5]

Text

This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 21 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[6]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[7][a]

Old Testament references

Analysis

A parallel pattern of sequence is observed in the final sections of 2 Kings between 2 Kings 11–20 and 2 Kings 21–25, as follows:[10]

- A. Athaliah, daughter of Ahab, kills royal seed (2 Kings 11:1)

- B. Joash reigns (2 Kings 11–12)

- C. Quick sequence of kings of Israel and Judah (2 Kings 13–16)

- D. Fall of Samaria (2 Kings 17)

- E. Revival of Judah under Hezekiah (2 Kings 18–20)

- D. Fall of Samaria (2 Kings 17)

- C. Quick sequence of kings of Israel and Judah (2 Kings 13–16)

- B. Joash reigns (2 Kings 11–12)

- A'. Manasseh, a king like Ahab, promotes idolatry and kills the innocence (2 Kings 21)

- B'. Josiah reigns (2 Kings 22–23)

- C'. Quick succession of kings of Judah (2 Kings 24)

- D'. Fall of Jerusalem (2 Kings 25)

- E'. Elevation of Jehoiachin (2 Kings 25:27–30)[10]

- D'. Fall of Jerusalem (2 Kings 25)

- C'. Quick succession of kings of Judah (2 Kings 24)

- B'. Josiah reigns (2 Kings 22–23)

Hezekiah’s illness and recovery (20:1–11)

This passage records the miraculous healing of Hezekiah from mortal illness as a corollary with the account of Jerusalem's deliverance, both by YHWH.[11] The prophet Isaiah acted as the messenger of YHWH, first to announce the 'prophecy of woe' that Hezekiah would die (verse 1b; cf. 2 Kings 1:16), later to announce a positive prophecy: Hezekiah would recover (and receive the addition of fifteen years of life, verse 6a) and to order a 'fig paste' to be spread on the diseased part of his body, 'so that he may recover' (verse 7; cf. Isaiah 38:21).[12] The king asked for a sign that he really would get healed (verse 8a), so YHWH had the shadow on the sundial (put up by Hezekiah's father, Ahaz) to move back: a sign that 'Hezekiah's life-clock' had also been turned back (w. 9–11).[5]

Narrative in the parallel passage in Isaiah 38 differs extensively in some parts:[13]

- Isaiah did not include 'the sake of my servant David' (verse 6 here)

- The statement about Isaiah's remedy and Hezekiah's request of sign (verses 7–8 here) are placed at the end of passage (Isaiah 38:21–22) following Hezekiah's prayer of thanksgiving (Isaiah 38:9–20)

- 2 Kings 20:9 has Isaiah stating the sign to Hezekiah, whereas Isaiah 38:6–7 emphasize that the sign was from YHWH.

- 2 Kings 20:9b–11 has Hezekiah somewhat skeptically asked for a more difficult act from YHWH: moving the shadow backward, whereas Isaiah 38:8 has the return of the shadow as direct response of YHWH to Hezekiah.[13]

The additional of fifteen years correlates Hezekiah's illness with Sennacherib's siege of Jerusalem which occurred in the fourteenth year (2 Kings 18:13) of Hezekiah's reign making a total of twenty nine years (2 Kings 18:2).[14]

Verse 7

- And Isaiah said, Take a lump of figs. And they took and laid it on the boil, and he recovered.[15]

- Cross reference: Isaiah 38:21

- "Lump [of figs]": or "cake [of figs]", in the construct-state; to render the word דְּבֶ֣לֶת, də-ḇe-leṯ (cf. 1 Samuel 25:18; 1 Samuel 30:12; 1 Chronicles 12:40), that is, 'figs closely pressed together for better keeping when they were dried.'[16] The remedy using 'fig paste' is still used among the 'Easterns' and in ancient times were noted by some writers such as Dioscorides, Jerome,[17] and Pliny (in 'Nat'., 23.7.122).[14]

The rabbis, in their homiletical explanations, explain the action of taking a lump of figs and applying it to a boil as being a "miracle within a miracle," since the act of plaistering a boil with figs has the ordinary effect of aggravating a skin-condition, and, yet, Hezekiah was cured of his skin-condition.[18]

Hezekiah shows his treasures; end of his reign (20:12–21)

This passage includes two episodes: one account of the Babylonian envoys dispatched by Merodach-Baladan following Hezekiah's illness (verses 12–13) and an account of Isaiah's confronting Hezekiah for showing his treasures to the envoys (verses 14–19).[19] Historical records to date suggest that this event more likely took place before 701 BCE, when the anti-Assyrian coalition would form following the death of Sargon II in 705 BCE, and Hezekiah's effort to impress Babylon by showing off his treasures would indicated a 'preparation for alliance and revolt'.[20][21] According to the narrative, Hezekiah's act caused the prophet Isaiah to be critical of the king, which conforms with the strong criticism of Hezekiah's alliance policy in Isaiah 30–31.[21] The concluding regnal formula on Hezekiah (verses 20–21) contains a quote from the Annals of the Kings of Judah, which also mention the construction of Siloam tunnel to carry water from Gihon Spring under the city of David to the Pool of Siloam[22][23][24] within city walls of Jerusalem (cf. 2 Chronicles 32:3–4; the remains of the fortifications have been excavated in modern times).[21][25]

Verse 20

- And the rest of the acts of Hezekiah, and all his might, and how he made a pool, and a conduit, and brought water into the city, are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Judah?[26]

- "Pool": based on archaeological findings is the Pool of Siloam.[17]

- "Conduit": connected to the pool of Siloam should refer to the Siloam Tunnel.[17]

Verse 21

- And Hezekiah slept with his fathers, and Manasseh his son reigned in his place.[27]

- "Slept with his fathers": that is, "died and joined his ancestors"[28]

Archaeology

Hezekiah

Extra-biblical sources specify Hezekiah by name, along with his reign and influence. "Historiographically, his reign is noteworthy for the convergence of a variety of biblical sources and diverse extrabiblical evidence often bearing on the same events. Significant data concerning Hezekiah appear in the Deuteronomistic History, the Chronicler, Isaiah, Assyrian annals and reliefs, Israelite epigraphy, and, increasingly, stratigraphy".[29] Archaeologist Amihai Mazar calls the tensions between Assyria and Judah "one of the best-documented events of the Iron Age" and Hezekiah's story is one of the best to cross-reference with the rest of the Mid Eastern world's historical documents.[30]

Several bullae bearing the name of Hezekiah have been found:

- a royal bulla with the inscription in ancient Hebrew script: "Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah" (between 727 and 698 BCE).[31][32][33][34]

- seals with the inscription: "Belonging to [the] servant of Hezekiah"

Other artifacts bearing the name "Hezekiah" include LMLK stored jars along the border with Assyria "demonstrate careful preparations to counter Sennacherib's likely route of invasion" and show "a notable degree of royal control of towns and cities which would facilitate Hezekiah's destruction of rural sacrificial sites and his centralization of worship in Jerusalem".[29] Evidence suggests they were used throughout his 29-year reign[35] and the Siloam inscription.[36]

Manasseh

Manasseh is mentioned in the Esarhaddon Prism (dates to 673–672 BCE), discovered by archaeologist Reginald Campbell Thompson during the 1927–28 excavation season at the ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh.[37] The 493 lines of cuneiform inscribed on the sides of the prism describe the history of King Esarhaddon's reign and an account of the reconstruction of the Assyrian palace in Babylon, which reads "Together 22 kings of Hatti [this land includes Israel], the seashore and the islands. All these I sent out and made them transport under terrible difficulties"; one of these 22 kings was King Manasseh of Judah ("Menasii šar [âlu]Iaudi").[37]

A record by Esarhaddon's son and successor, Ashurbanipal, mentions "Manasseh, king of Judah" who contributed to the invasion force against Egypt.[38]

See also

Notes

- ^ The whole book of 2 Kings is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[8]

References

- ^ Halley 1965, p. 211.

- ^ Collins 2014, p. 288.

- ^ McKane 1993, p. 324.

- ^ Sweeney 2007, pp. 419–424.

- ^ a b Dietrich 2007, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b 2 Kings 20, Berean Study Bible

- ^ a b Leithart 2006, p. 266.

- ^ Sweeney 2007, p. 420.

- ^ Dietrich 2007, p. 261.

- ^ a b Sweeney 2007, p. 421.

- ^ a b Sweeney 2007, p. 422.

- ^ 2 Kings 20:7 KJV

- ^ Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. 2 Kings 20. Accessed 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Exell, Joseph S.; Spence-Jones, Henry Donald Maurice (Editors). On "2 Kings 20". In: The Pulpit Commentary. 23 volumes. First publication: 1890. Accessed 24 April 2019.

- ^ Rashi and Rabbi David Kimhi on 2 Kings 20:7

- ^ Sweeney 2007, p. 423.

- ^ Sweeney 2007, pp. 423–424.

- ^ a b c Dietrich 2007, p. 262.

- ^ Image of exit from Siloam Tunnel

- ^ Holy Land Photos

- ^ Pool of Siloam image

- ^ Sweeney 2007, p. 424.

- ^ 2 Kings 20:20 KJV

- ^ 2 Kings 20:21 ESV

- ^ Note on 2 Kings 20:21 in NKJV

- ^ a b "Hezekiah." The Anchor Bible Dictionary. 1992. Print.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel and Amihai Mazar. The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel. Leiden: Brill, 2007

- ^ Eisenbud, Daniel K. (2015). "First Ever Seal Impression of an Israelite or Judean King Exposed near Temple Mount". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ ben Zion, Ilan (2 December 2015). ""לחזקיהו [בן] אחז מלך יהדה" "Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah"". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "First ever seal impression of an Israelite or Judean king exposed near Temple Mount". 2 December 2015.

- ^ Alyssa Navarro, Archaeologists Find Biblical-Era Seal Of King Hezekiah In Jerusalem "Tech Times" December 6

- ^ Grena, G.M. (2004). LMLK--A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1 (1 ed.). 4000 Years of Writing History. p. 338. ISBN 978-0974878607.

- ^ Archaeological Study Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005. Print.

- ^ a b "The Esarhaddon Prism". The British Museum. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

Column 4: "Adumutu (is) the strong city of the Arabians, which Sennacherib, king of Assyria, the father, my begetter, had conquered"

- ^ Reinsch, Warren. Esarhaddon Prism Proves King Manasseh. An ancient Babylonian clay prism confirms two biblical kings and the accuracy of the Bible narrative. The Trumpet, May 2, 2019.

Sources

- Cogan, Mordechai; Tadmor, Hayim (1988). II Kings: A New Translation. Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries. Vol. 11. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385023887.

- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 9781451469233.

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288810.

- Dietrich, Walter (2007). "13. 1 and 2 Kings". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 232–266. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Fretheim, Terence E (1997). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25565-7.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Huey, F. B. (1993). The New American Commentary - Jeremiah, Lamentations: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture, NIV Text. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805401165.

- Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431258.

- McKane, William (1993). "Kings, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- Nelson, Richard Donald (1987). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Pritchard, James B (1969). Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament (3 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691035031.

- Sweeney, Marvin (2007). I & II Kings: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Melachim II - II Kings - Chapter 20 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 2 Kings chapter 20. Bible Gateway