5 Vulpeculae

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Vulpecula |

| Right ascension | 19h 26m 13.2463s[1] |

| Declination | +20° 05′ 51.8394″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.65±0.010[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | A0 V[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (U) | 5.62±0.012[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (B) | 5.66±0.011[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −20.9±2.9[4] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +3.395±0.114[1] mas/yr Dec.: −34.787±0.137[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 13.8921 ± 0.0900 mas[1] |

| Distance | 235 ± 2 ly (72.0 ± 0.5 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 1.29[5] |

| Details[3] | |

| Mass | 2.33±0.02 M☉ |

| Radius | 2.7[6] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 34±2 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.0[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 9,840+91 −90 K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 154 km/s |

| Age | 198[7] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

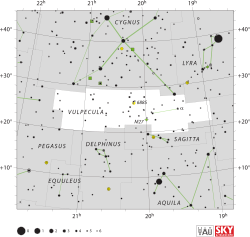

5 Vulpeculae is a single,[9] white-hued star in the northern constellation of Vulpecula.[8] It is situated amidst a random concentration of bright stars designated Collinder 399,[10] or Brocchi's Cluster. This is a faint star that is just visible to the naked eye with an apparent visual magnitude of 5.60.[4] Based upon an annual parallax shift of 13.8921±0.0900 mas,[1] it is located around 235 light years from the Sun. It is moving closer with a heliocentric radial velocity of −21 km/s,[4] and will make its closest approach in 2.5 million years at a separation of around 120 ly (36.89 pc).[5]

This is a young A-type main-sequence star with a stellar classification of A0 V.[3] It is a rapidly rotating star[11] with a projected rotational velocity of 154 km/s.[3] The star has an estimated 2.33[3] times the mass of the Sun and about 2.7[6] times the Sun's radius. It is radiating 34 times the Sun's luminosity from its photosphere at an effective temperature of 8,940 K.[3]

A warm debris disk was detected by the Spitzer Space Telescope at a temperature of 206 K (−89 °F; −67 °C), orbiting 13 Astronomical units from the host star.[12] Although this finding has not been directly detected, the emission signature indicates the disk is in the form of a thin ring. The emission displays weak transient absorption features that are indicative of kilometer-sized exocomets that are undergoing evaporation as they approach the host star.[11] These absorption features have been observed to vary on time scales of hours, days, or months.[13]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c Harmanec, P.; et al. (2020). "A new study of the spectroscopic binary 7 Vul with a Be star primary". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 639. Table A.1. arXiv:2005.11089. Bibcode:2020A&A...639A..32H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202037964. S2CID 218862853.

- ^ a b c d e f Zorec, J.; Royer, F. (2012), "Rotational velocities of A-type stars. IV. Evolution of rotational velocities", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 537: A120, arXiv:1201.2052, Bibcode:2012A&A...537A.120Z, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117691, S2CID 55586789.

- ^ a b c Gontcharov, G. A. (November 2006), "Pulkovo Compilation of Radial Velocities for 35 495 Hipparcos stars in a common system", Astronomy Letters, 32 (11): 759–771, arXiv:1606.08053, Bibcode:2006AstL...32..759G, doi:10.1134/S1063773706110065, S2CID 119231169.

- ^ a b Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012), "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation", Astronomy Letters, 38 (5): 331, arXiv:1108.4971, Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A, doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015, S2CID 119257644.

- ^ a b Pasinetti Fracassini, L. E.; et al. (February 2001), "Catalogue of Apparent Diameters and Absolute Radii of Stars (CADARS)", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 367 (2) (3rd ed.): 521–524, arXiv:astro-ph/0012289, Bibcode:2001A&A...367..521P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000451, S2CID 425754.

- ^ a b Chen, Christine H.; et al. (2014), "The Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph Debris Disk Catalog. I. Continuum Analysis of Unresolved Targets", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement, 211 (3): 22, Bibcode:2014ApJS..211...25C, doi:10.1088/0067-0049/211/2/25, 25.

- ^ a b "5 Vul". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ^ Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (September 2008), "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 389 (2): 869–879, arXiv:0806.2878, Bibcode:2008MNRAS.389..869E, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x, S2CID 14878976.

- ^ Baumgardt, H. (December 1998), "The nature of some doubtful open clusters as revealed by HIPPARCOS", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 340: 402–414, Bibcode:1998A&A...340..402B.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Sharon L.; Welsh, Barry Y. (October 2012), "Detection of Variable Gaseous Absorption Features in the Debris Disks Around Young A-type Stars", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 124 (920): 1042, Bibcode:2012PASP..124.1042M, doi:10.1086/668293

- ^ Morales, Farisa Y.; et al. (2009), "Spitzer mid-Ir Spectra of Dust Debris Around A and Late B Type Stars: Asteroid Belt Analogs and Power-Law Dust Distributions" (PDF), The Astrophysical Journal, 699 (2): 1067–1086, Bibcode:2009ApJ...699.1067M, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/699/2/1067, S2CID 45235873.

- ^ Montgomery, Sharon L.; Welsh, B.; Lallement, R.; Timbs, B. W. (January 2014), "Exocomet Gas: Now You See It, Now You Don't", American Astronomical Society, AAS Meeting #223, 223: 401.02, Bibcode:2014AAS...22340102M, 401.02.

External links

- 5 Vulpeculae on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images