Acoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician while someone working in the field of acoustics technology may be called an acoustical engineer. The application of acoustics is present in almost all aspects of modern society with the most obvious being the audio and noise control industries.

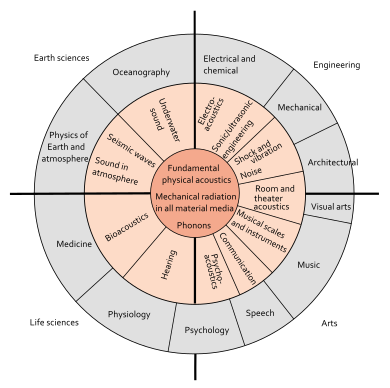

Hearing is one of the most crucial means of survival in the animal world and speech is one of the most distinctive characteristics of human development and culture. Accordingly, the science of acoustics spreads across many facets of human society—music, medicine, architecture, industrial production, warfare and more. Likewise, animal species such as songbirds and frogs use sound and hearing as a key element of mating rituals or for marking territories. Art, craft, science and technology have provoked one another to advance the whole, as in many other fields of knowledge. Robert Bruce Lindsay's "Wheel of Acoustics" is a well accepted overview of the various fields in acoustics.[1]

History

Etymology

The word "acoustic" is derived from the Greek word ἀκουστικός (akoustikos), meaning "of or for hearing, ready to hear"[2] and that from ἀκουστός (akoustos), "heard, audible",[3] which in turn derives from the verb ἀκούω(akouo), "I hear".[4]

The Latin synonym is "sonic", after which the term sonics used to be a synonym for acoustics[5] and later a branch of acoustics.[5] Frequencies above and below the audible range are called "ultrasonic" and "infrasonic", respectively.

Early research in acoustics

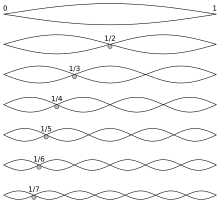

In the 6th century BC, the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras wanted to know why some combinations of musical sounds seemed more beautiful than others, and he found answers in terms of numerical ratios representing the harmonic overtone series on a string. He is reputed to have observed that when the lengths of vibrating strings are expressible as ratios of integers (e.g. 2 to 3, 3 to 4), the tones produced will be harmonious, and the smaller the integers the more harmonious the sounds. For example, a string of a certain length would sound particularly harmonious with a string of twice the length (other factors being equal). In modern parlance, if a string sounds the note C when plucked, a string twice as long will sound a C an octave lower. In one system of musical tuning, the tones in between are then given by 16:9 for D, 8:5 for E, 3:2 for F, 4:3 for G, 6:5 for A, and 16:15 for B, in ascending order.[6]

Aristotle (384–322 BC) understood that sound consisted of compressions and rarefactions of air which "falls upon and strikes the air which is next to it...",[7][8] a very good expression of the nature of wave motion. On Things Heard, generally ascribed to Strato of Lampsacus, states that the pitch is related to the frequency of vibrations of the air and to the speed of sound.[9]

In about 20 BC, the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius wrote a treatise on the acoustic properties of theaters including discussion of interference, echoes, and reverberation—the beginnings of architectural acoustics.[10] In Book V of his De architectura (The Ten Books of Architecture) Vitruvius describes sound as a wave comparable to a water wave extended to three dimensions, which, when interrupted by obstructions, would flow back and break up following waves. He described the ascending seats in ancient theaters as designed to prevent this deterioration of sound and also recommended bronze vessels (echea) of appropriate sizes be placed in theaters to resonate with the fourth, fifth and so on, up to the double octave, in order to resonate with the more desirable, harmonious notes.[11][12][13]

During the Islamic golden age, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) is believed to have postulated that the speed of sound was much slower than the speed of light.[14][15]

The physical understanding of acoustical processes advanced rapidly during and after the Scientific Revolution. Mainly Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) but also Marin Mersenne (1588–1648), independently, discovered the complete laws of vibrating strings (completing what Pythagoras and Pythagoreans had started 2000 years earlier). Galileo wrote "Waves are produced by the vibrations of a sonorous body, which spread through the air, bringing to the tympanum of the ear a stimulus which the mind interprets as sound", a remarkable statement that points to the beginnings of physiological and psychological acoustics. Experimental measurements of the speed of sound in air were carried out successfully between 1630 and 1680 by a number of investigators, prominently Mersenne. Meanwhile, Newton (1642–1727) derived the relationship for wave velocity in solids, a cornerstone of physical acoustics (Principia, 1687).

Age of Enlightenment and onward

Substantial progress in acoustics, resting on firmer mathematical and physical concepts, was made during the eighteenth century by Euler (1707–1783), Lagrange (1736–1813), and d'Alembert (1717–1783). During this era, continuum physics, or field theory, began to receive a definite mathematical structure. The wave equation emerged in a number of contexts, including the propagation of sound in air.[16]

In the nineteenth century the major figures of mathematical acoustics were Helmholtz in Germany, who consolidated the field of physiological acoustics, and Lord Rayleigh in England, who combined the previous knowledge with his own copious contributions to the field in his monumental work The Theory of Sound (1877). Also in the 19th century, Wheatstone, Ohm, and Henry developed the analogy between electricity and acoustics.

The twentieth century saw a burgeoning of technological applications of the large body of scientific knowledge that was by then in place. The first such application was Sabine's groundbreaking work in architectural acoustics, and many others followed. Underwater acoustics was used for detecting submarines in the first World War. Sound recording and the telephone played important roles in a global transformation of society. Sound measurement and analysis reached new levels of accuracy and sophistication through the use of electronics and computing. The ultrasonic frequency range enabled wholly new kinds of application in medicine and industry. New kinds of transducers (generators and receivers of acoustic energy) were invented and put to use.

Definition

Acoustics is defined by ANSI/ASA S1.1-2013 as "(a) Science of sound, including its production, transmission, and effects, including biological and psychological effects. (b) Those qualities of a room that, together, determine its character with respect to auditory effects."

The study of acoustics revolves around the generation, propagation and reception of mechanical waves and vibrations.

The steps shown in the above diagram can be found in any acoustical event or process. There are many kinds of cause, both natural and volitional. There are many kinds of transduction process that convert energy from some other form into sonic energy, producing a sound wave. There is one fundamental equation that describes sound wave propagation, the acoustic wave equation, but the phenomena that emerge from it are varied and often complex. The wave carries energy throughout the propagating medium. Eventually this energy is transduced again into other forms, in ways that again may be natural and/or volitionally contrived. The final effect may be purely physical or it may reach far into the biological or volitional domains. The five basic steps are found equally well whether we are talking about an earthquake, a submarine using sonar to locate its foe, or a band playing in a rock concert.

The central stage in the acoustical process is wave propagation. This falls within the domain of physical acoustics. In fluids, sound propagates primarily as a pressure wave. In solids, mechanical waves can take many forms including longitudinal waves, transverse waves and surface waves.

Acoustics looks first at the pressure levels and frequencies in the sound wave and how the wave interacts with the environment. This interaction can be described as either a diffraction, interference or a reflection or a mix of the three. If several media are present, a refraction can also occur. Transduction processes are also of special importance to acoustics.

Fundamental concepts

Wave propagation: pressure levels

In fluids such as air and water, sound waves propagate as disturbances in the ambient pressure level. While this disturbance is usually small, it is still noticeable to the human ear. The smallest sound that a person can hear, known as the threshold of hearing, is nine orders of magnitude smaller than the ambient pressure. The loudness of these disturbances is related to the sound pressure level (SPL) which is measured on a logarithmic scale in decibels.

Wave propagation: frequency

Physicists and acoustic engineers tend to discuss sound pressure levels in terms of frequencies, partly because this is how our ears interpret sound. What we experience as "higher pitched" or "lower pitched" sounds are pressure vibrations having a higher or lower number of cycles per second. In a common technique of acoustic measurement, acoustic signals are sampled in time, and then presented in more meaningful forms such as octave bands or time frequency plots. Both of these popular methods are used to analyze sound and better understand the acoustic phenomenon.

The entire spectrum can be divided into three sections: audio, ultrasonic, and infrasonic. The audio range falls between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz. This range is important because its frequencies can be detected by the human ear. This range has a number of applications, including speech communication and music. The ultrasonic range refers to the very high frequencies: 20,000 Hz and higher. This range has shorter wavelengths which allow better resolution in imaging technologies. Medical applications such as ultrasonography and elastography rely on the ultrasonic frequency range. On the other end of the spectrum, the lowest frequencies are known as the infrasonic range. These frequencies can be used to study geological phenomena such as earthquakes.

Analytic instruments such as the spectrum analyzer facilitate visualization and measurement of acoustic signals and their properties. The spectrogram produced by such an instrument is a graphical display of the time varying pressure level and frequency profiles which give a specific acoustic signal its defining character.

Transduction in acoustics

A transducer is a device for converting one form of energy into another. In an electroacoustic context, this means converting sound energy into electrical energy (or vice versa). Electroacoustic transducers include loudspeakers, microphones, particle velocity sensors, hydrophones and sonar projectors. These devices convert a sound wave to or from an electric signal. The most widely used transduction principles are electromagnetism, electrostatics and piezoelectricity.

The transducers in most common loudspeakers (e.g. woofers and tweeters), are electromagnetic devices that generate waves using a suspended diaphragm driven by an electromagnetic voice coil, sending off pressure waves. Electret microphones and condenser microphones employ electrostatics—as the sound wave strikes the microphone's diaphragm, it moves and induces a voltage change. The ultrasonic systems used in medical ultrasonography employ piezoelectric transducers. These are made from special ceramics in which mechanical vibrations and electrical fields are interlinked through a property of the material itself.

Acoustician

An acoustician is an expert in the science of sound.[17]

Education

There are many types of acoustician, but they usually have a Bachelor's degree or higher qualification. Some possess a degree in acoustics, while others enter the discipline via studies in fields such as physics or engineering. Much work in acoustics requires a good grounding in Mathematics and science. Many acoustic scientists work in research and development. Some conduct basic research to advance our knowledge of the perception (e.g. hearing, psychoacoustics or neurophysiology) of speech, music and noise. Other acoustic scientists advance understanding of how sound is affected as it moves through environments, e.g. underwater acoustics, architectural acoustics or structural acoustics. Other areas of work are listed under subdisciplines below. Acoustic scientists work in government, university and private industry laboratories. Many go on to work in Acoustical Engineering. Some positions, such as Faculty (academic staff) require a Doctor of Philosophy.

Subdisciplines

Archaeoacoustics

Archaeoacoustics, also known as the archaeology of sound, is one of the only ways to experience the past with senses other than our eyes.[18] Archaeoacoustics is studied by testing the acoustic properties of prehistoric sites, including caves. Iegor Rezkinoff, a sound archaeologist, studies the acoustic properties of caves through natural sounds like humming and whistling.[19] Archaeological theories of acoustics are focused around ritualistic purposes as well as a way of echolocation in the caves. In archaeology, acoustic sounds and rituals directly correlate as specific sounds were meant to bring ritual participants closer to a spiritual awakening.[18] Parallels can also be drawn between cave wall paintings and the acoustic properties of the cave; they are both dynamic.[19] Because archaeoacoustics is a fairly new archaeological subject, acoustic sound is still being tested in these prehistoric sites today.

Aeroacoustics

Aeroacoustics is the study of noise generated by air movement, for instance via turbulence, and the movement of sound through the fluid air. This knowledge was applied in the 1920s and '30s to detect aircraft before radar was invented and is applied in acoustical engineering to study how to quieten aircraft. Aeroacoustics is important for understanding how wind musical instruments work.[20]

Acoustic signal processing

Acoustic signal processing is the electronic manipulation of acoustic signals. Applications include: active noise control; design for hearing aids or cochlear implants; echo cancellation; music information retrieval, and perceptual coding (e.g. MP3 or Opus).[21]

Architectural acoustics

Architectural acoustics (also known as building acoustics) involves the scientific understanding of how to achieve good sound within a building.[22] It typically involves the study of speech intelligibility, speech privacy, music quality, and vibration reduction in the built environment.[23] Commonly studied environments are hospitals, classrooms, dwellings, performance venues, recording and broadcasting studios. Focus considerations include room acoustics, airborne and impact transmission in building structures, airborne and structure-borne noise control, noise control of building systems and electroacoustic systems.[24]

Bioacoustics

Bioacoustics is the scientific study of the hearing and calls of animal calls, as well as how animals are affected by the acoustic and sounds of their habitat.[25]

Electroacoustics

This subdiscipline is concerned with the recording, manipulation and reproduction of audio using electronics.[26] This might include products such as mobile phones, large scale public address systems or virtual reality systems in research laboratories.

Environmental noise and soundscapes

Environmental acoustics is concerned with noise and vibration caused by railways,[27] road traffic, aircraft, industrial equipment and recreational activities.[28] The main aim of these studies is to reduce levels of environmental noise and vibration. Research work now also has a focus on the positive use of sound in urban environments: soundscapes and tranquility.[29]

Musical acoustics

Musical acoustics is the study of the physics of acoustic instruments; the audio signal processing used in electronic music; the computer analysis of music and composition, and the perception and cognitive neuroscience of music.[30]

Noise

The goal this acoustics sub-discipline is to reduce the impact of unwanted sound. Scope of noise studies includes the generation, propagation, and impact on structures, objects, and people.

- Innovative model development

- Measurement techniques

- Mitigation strategies

- Input to the establishment of standards and regulations

Noise research investigates the impact of noise on humans and animals to include work in definitions, abatement, transportation noise, hearing protection, Jet and rocket noise, building system noise and vibration, atmospheric sound propagation, soundscapes, and low-frequency sound.

Psychoacoustics

Many studies have been conducted to identify the relationship between acoustics and cognition, or more commonly known as psychoacoustics, in which what one hears is a combination of perception and biological aspects.[31] The information intercepted by the passage of sound waves through the ear is understood and interpreted through the brain, emphasizing the connection between the mind and acoustics. Psychological changes have been seen as brain waves slow down or speed up as a result of varying auditory stimulus which can in turn affect the way one thinks, feels, or even behaves.[32] This correlation can be viewed in normal, everyday situations in which listening to an upbeat or uptempo song can cause one's foot to start tapping or a slower song can leave one feeling calm and serene. In a deeper biological look at the phenomenon of psychoacoustics, it was discovered that the central nervous system is activated by basic acoustical characteristics of music.[33] By observing how the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spine, is influenced by acoustics, the pathway in which acoustic affects the mind, and essentially the body, is evident.[33]

Speech

Acousticians study the production, processing and perception of speech. Speech recognition and Speech synthesis are two important areas of speech processing using computers. The subject also overlaps with the disciplines of physics, physiology, psychology, and linguistics.[34]

Structural Vibration and Dynamics

Structural acoustics is the study of motions and interactions of mechanical systems with their environments and the methods of their measurement, analysis, and control. There are several sub-disciplines found within this regime:

- Modal Analysis

- Material characterization

- Structural health monitoring

- Acoustic Metamaterials

- Friction Acoustics

Applications might include: ground vibrations from railways; vibration isolation to reduce vibration in operating theatres; studying how vibration can damage health (vibration white finger); vibration control to protect a building from earthquakes, or measuring how structure-borne sound moves through buildings.[35]

Ultrasonics

Ultrasonics deals with sounds at frequencies too high to be heard by humans. Specialisms include medical ultrasonics (including medical ultrasonography), sonochemistry, ultrasonic testing, material characterisation and underwater acoustics (sonar).[36]

Underwater acoustics

Underwater acoustics is the scientific study of natural and man-made sounds underwater. Applications include sonar to locate submarines, underwater communication by whales, climate change monitoring by measuring sea temperatures acoustically, sonic weapons,[37] and marine bioacoustics.[38]

Research

Professional societies

- The Acoustical Society of America (ASA)

- Australian Acoustical Society (AAS)

- The European Acoustics Association (EAA)

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

- Institute of Acoustics (IoA UK)

- The Audio Engineering Society (AES)

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Noise Control and Acoustics Division (ASME-NCAD)

- International Commission for Acoustics (ICA)

- American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Aeroacoustics (AIAA)

- International Computer Music Association (ICMA)

Academic journals

- Acoustics | An Open Access Journal from MDPI

- Acoustics Today

- Acta Acustica united with Acustica

- Advances in Acoustics and Vibration

- Applied Acoustics

- Building Acoustics

- IEEE Transacions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control

- Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (JASA)

- Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Express Letters (JASA-EL)

- Journal of the Audio Engineering Society

- Journal of Sound and Vibration (JSV)

- Journal of Vibration and Acoustics American Society of Mechanical Engineers

- MDPI Acoustics

- Noise Control Engineering Journal

- SAE International Journal of Vehicle Dynamics, Stability and NVH

- Ultrasonics (journal)

- Ultrasonics Sonochemistry

- Wave Motion

Conferences

See also

- Outline of acoustics

- Acoustic attenuation

- Acoustic emission

- Acoustic engineering

- Acoustic impedance

- Acoustic levitation

- Acoustic location

- Acoustic phonetics

- Acoustic streaming

- Acoustic tags

- Acoustic thermometry

- Acoustic wave

- Audiology

- Auditory illusion

- Diffraction

- Doppler effect

- Fisheries acoustics

- Friction acoustics

- Helioseismology

- Lamb wave

- Linear elasticity

- The Little Red Book of Acoustics (in the UK)

- Longitudinal wave

- Musicology

- Music therapy

- Noise pollution

- Phonon

- Picosecond ultrasonics

- Rayleigh wave

- Shock wave

- Seismology

- Sonification

- Sonochemistry

- Soundproofing

- Soundscape

- Sonic boom

- Sonoluminescence

- Surface acoustic wave

- Thermoacoustics

- Transverse wave

- Wave equation

References

- ^ "What is acoustics?", Acoustical Research Group, Brigham Young University, archived from the original on 2021-04-16, retrieved 2021-04-16

- ^ Akoustikos Archived 2020-01-23 at the Wayback Machine Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- ^ Akoustos Archived 2020-01-23 at the Wayback Machine Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- ^ Akouo Archived 2020-01-23 at the Wayback Machine Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- ^ a b Kenneth Neville Westerman (1947). Emergent Voice. C. F. Westerman. Archived from the original on 2023-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ^ C. Boyer and U. Merzbach. A History of Mathematics. Wiley 1991, p. 55.

- ^ "How Sound Propagates" (PDF). Princeton University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 9 February 2016. (quoting from Aristotle's Treatise on Sound and Hearing)

- ^ Whewell, William, 1794–1866. History of the inductive sciences : from the earliest to the present times. Volume 2. Cambridge. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-511-73434-2. OCLC 889953932.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Greek musical writings. Barker, Andrew (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2004. p. 98. ISBN 0-521-38911-9. OCLC 63122899.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ ACOUSTICS, Bruce Lindsay, Dowden – Hutchingon Books Publishers, Chapter 3

- ^ Vitruvius Pollio, Vitruvius, the Ten Books on Architecture (1914) Tr. Morris Hickey Morgan BookV, Sec.6–8

- ^ Vitruvius article @Wikiquote

- ^ Ernst Mach, Introduction to The Science of Mechanics: A Critical and Historical Account of its Development (1893, 1960) Tr. Thomas J. McCormack

- ^ Sparavigna, Amelia Carolina (December 2013). "The Science of Al-Biruni" (PDF). International Journal of Sciences. 2 (12): 52–60. arXiv:1312.7288. Bibcode:2013arXiv1312.7288S. doi:10.18483/ijSci.364. S2CID 119230163. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St. Andrews, Scotland. November 1999. Archived from the original on 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ Pierce, Allan D. (1989). Acoustics : an introduction to its physical principles and applications (1989 ed.). Woodbury, N.Y.: Acoustical Society of America. ISBN 0-88318-612-8. OCLC 21197318.

- ^ Schwarz, C (1991). Chambers concise dictionary.

- ^ a b Clemens, Martin J. (2016-01-31). "Archaeoacoustics: Listening to the Sounds of History". The Daily Grail. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Emma (2017-04-13). "With Archaeoacoustics, Researchers Listen for Clues to the Prehistoric Past". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ da Silva, Andrey Ricardo (2009). Aeroacoustics of Wind Instruments: Investigations and Numerical Methods. VDM Verlag. ISBN 978-3639210644.

- ^ Slaney, Malcolm; Patrick A. Naylor (2011). "Trends in Audio and Acoustic Signal Processing". ICASSP.

- ^ Morfey, Christopher (2001). Dictionary of Acoustics. Academic Press. p. 32.

- ^ Templeton, Duncan (1993). Acoustics in the Built Environment: Advice for the Design Team. Architectural Press. ISBN 978-0750605380.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Bioacoustics - the International Journal of Animal Sound and its Recording". Taylor & Francis. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Acoustical Society of America. "Acoustics and You (A Career in Acoustics?)". Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Krylov, V.V., ed. (2001). Noise and Vibration from High-speed Trains. Thomas Telford. ISBN 9780727729637.

- ^ World Health Organisation (2011). Burden of disease from environmental noise (PDF). WHO. ISBN 978-92-890-0229-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Kang, Jian (2006). Urban Sound Environment. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0415358576.

- ^ Technical Committee on Musical Acoustics (TCMU) of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA). "ASA TCMU Home Page". Archived from the original on 2001-06-13. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Iakovides, Stefanos A.; Iliadou, Vassiliki TH; Bizeli, Vassiliki TH; Kaprinis, Stergios G.; Fountoulakis, Konstantinos N.; Kaprinis, George S. (2004-03-29). "Psychophysiology and psychoacoustics of music: Perception of complex sound in normal subjects and psychiatric patients". Annals of General Hospital Psychiatry. 3 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1475-2832-3-6. ISSN 1475-2832. PMC 400748. PMID 15050030.

- ^ "Psychoacoustics: The Power of Sound". Memtech Acoustical. 2016-02-11. Archived from the original on 2019-04-15. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ^ a b Green, David M. (1960). "Psychoacoustics and Detection Theory". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 32 (10): 1189–1203. Bibcode:1960ASAJ...32.1189G. doi:10.1121/1.1907882. ISSN 0001-4966.

- ^ "Technical Committee on Speech Communication". Acoustical Society of America. Archived from the original on 2018-11-05. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ "Structural Acoustics & Vibration Technical Committee". Archived from the original on 10 August 2018.

- ^ Ensminger, Dale (2012). Ultrasonics: Fundamentals, Technologies, and Applications. CRC Press. pp. 1–2.

- ^ D. Lohse, B. Schmitz & M. Versluis (2001). "Snapping shrimp make flashing bubbles". Nature. 413 (6855): 477–478. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..477L. doi:10.1038/35097152. PMID 11586346. S2CID 4429684.

- ^ ASA Underwater Acoustics Technical Committee. "Underwater Acoustics". Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

Further reading

- Attenborough K, Postema M (2008). A pocket-sized introduction to acoustics. Kingston upon Hull: University of Hull. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7504060. ISBN 978-90-812588-2-1.

- Benade AH (1976). Fundamentals of Musical Acoustics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502030-4. OCLC 2270137.

- Biryukov SV, Gulyaev YV, Krylov VV, Plessky VP (1995). Surface Acoustic Waves in Inhomogeneous Media. Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-58460-5.

- Crocker MJ, ed. (1997). Encyclopedia of Acoustics. Hoboken: Wiley. OCLC 441305164.

- Falkovich G (2011). Fluid Mechanics, a short course for physicists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00575-4.

- Fahy FJ, Gardonio P (2007). Sound and Structural Vibration: Radiation, Transmission and Response (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-047110-5.

- Junger MC, Feit D (1986). Sound, Structures and Their Interaction (2nd ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press. Archived from the original on 2014-06-05.

- Kinsler LE (1999). Fundamentals of Acoustics (4th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-04718-4-789-2.

- Mason WP, Thurston RN (1981). Physical Acoustics. Heidelberg: Springer. Archived from the original on 2013-12-25.

- Morse PM, Ingard KU (1986). Theoretical Acoustics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08425-4.

- Pierce AD (1989). Acoustics: An Introduction to its Physical Principles and Applications. Melville: Acoustical Society of America. ISBN 0-88318-612-8.

- Raichel DR (2006). The Science and Applications of Acoustics (2nd ed.). Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 0-387-30089-9.

- Lord Rayleigh (1894). The Theory of Sound. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-8446-3028-1.

- Skudrzyk E (1971). The Foundations of Acoustics: Basic Mathematics and Basic Acoustics. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Stephens RW, Bate AE (1966). Acoustics and Vibrational Physics (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

- Wilson CE (2006). Noise Control (Revised ed.). Malabar: Krieger. ISBN 978-1-57524-237-8. OCLC 59223706.