Arsis and thesis

In music and prosody, arsis (/ˈɑːrsɪs/; plural arses, /ˈɑːrsiːz/) and thesis (/ˈθiːsɪs/; plural theses, /ˈθiːsiːz/)[2] are respectively the stronger and weaker parts of a musical measure or poetic foot. However, because of contradictions in the original definitions, writers use these words in different ways. In music, arsis is an unaccented note (upbeat), while the thesis is the downbeat.[3] However, in discussions of Latin and modern poetry the word arsis is generally used to mean the stressed syllable of the foot, that is, the ictus.[4]

Since the words are used in contradictory ways, the authority on Greek metre Martin West[5] recommends abandoning them and using substitutes such as ictus for the downbeat when discussing ancient poetry.[6] However, the use of the word ictus itself is very controversial.[7]

Greek and Roman definitions

Earliest use

The ancient Greek writers who mention the terms arsis and thesis are mostly from rather a late period (2nd-4th century AD), but it is thought that they continued an earlier tradition. For example, it is believed that Aristides Quintilianus (3rd or 4th century AD) adopted much of his theory from Aristotle's pupil Aristoxenus (4th century BC), who wrote on the theory of rhythm.[8]

Arsis ("raising") and thesis ("putting down or placing") originally seem to have meant the raising and lowering of the foot in marching or dancing. A Greek musicologist, Bacchius or Baccheios (c. 4th century AD),[9] states: "What do we mean by arsis? When our foot is in the air, when we are about to take a step. And by thesis? When it is on the ground."[10] Aristides Quintilianus similarly writes: "Arsis is the upwards motion of a part of the body, while thesis is the downwards motion of the same part."[11] And in general Aristotle (4th century BC) wrote: "All walking (poreia) consists of arsis and thesis."[12]

Because of the association between rhythm and stepping, the parts of a rhythmic sequence were referred to as "feet". Aristides Quintilianus (3rd or 4th century AD) writes: "A foot is part of an entire rhythm from which we recognise the whole. It has two parts: arsis and thesis."[13]

Aristoxenus appears to be the first writer in whose surviving work the word arsis is used specifically in connection with rhythm. Instead of thesis, he uses the word basis ("step"). However, in other Greek writers from Plato onwards, the word basis referred to the whole foot (i.e. the sequence of arsis and thesis).[14]

More frequently Aristoxenus refers to arsis and thesis respectively as the "up time" (ὁ ἄνω χρόνος, ho ánō khrónos) and the "down time" (ὁ κάτω χρόνος, ho kátō khrónos), or simply the "up" (τὸ ἄνω, tò ánō) and the "down" (τὸ κάτω, tò kátō).[15] The division of feet into "up" and "down" seems to go back at least as far as the 5th-century Damon of Athens, teacher of Pericles.[16]

Stefan Hagel writes: "Although the significance of the ancient conception [of upbeat and downbeat] and the applicability of the modern terms are disputed, there is no doubt that arsis and thesis refer to some type of accentuation actually felt by the ancients. Especially in instrumental music, this must have included a dynamic element, so that it makes good sense to transcribe the larger rhythmical units by means of modern bars."[17]

Elatio

Simultaneously with the definition of a raising of the foot, there existed another definition of arsis. The Roman writer Marius Victorinus (4th century AD), in part of his work attributed to a certain Aelius Festus Aphthonius, gave both definitions when he wrote: "What the Greeks call arsis and thesis, that is raising and putting down, indicate the movement of the foot. Arsis is the lifting (sublatio) of the foot without sound, thesis the placement (positio) of the foot with a sound. Arsis also means the elatio ("elevation") of a time-duration, sound or voice, thesis the placing-down (depositio) and some sort of contraction of syllables."[18] Lynch notes that Marius Victorinus in his writings carefully distinguishes sublatio in the first sense, when writing about poetic metre, from elatio in the second, when writing about the rhythm of music. Martianus Capella (5th century), when he translates Aristides, makes the same distinction.[19] Lynch argues that elatio here means a rise in pitch, but others consider it as meaning an increase in intensity or length.[20]

Writing about rhythm rather than metre, Aristides Quintilianus appears to have been using the second definition when he wrote: "Rhythm is a combination of durations put together in some definite order: and we call their modifications arsis and thesis, sound and calm (ψόφον καὶ ἠρεμίαν, psóphon kaì ēremían)."[21]

A similar use of the terms arsis and thesis is found in medical writing with reference to the pulse of the blood. The medical writer Galen (2nd century AD), noting that this usage goes back to Herophilos (4th/3rd century BC), and that it was based on an analogy with the musical terms, says that in measuring the pulse of the blood, the pulse itself was called the arsis, and the calm following the pulse was the thesis. For "calm" he uses the same term ἠρεμία (ēremía) that Aristides uses when talking about rhythm.[22]

Arsis and thesis in ancient Greek music

Writers on the rhythms of Greek music or dance usually described the first part of a foot as the arsis or "up" part. Aristoxenus writes: "Some feet are composed of two time units, both the up and the down; others of three, two up and one down, or one up and two down; still others of four, two up and two down."[23] Commentators have taken Aristoxenus here to be referring to trochaic (– ⏑) and iambic (⏑ –) feet, and saying that in trochaic feet, the long syllable is "up" i.e. in arsis, while in iambic feet, the short syllable is in arsis.[24]

Aristides Quintilianus (3rd or 4th century AD), however, specifies that the thesis comes first in some kinds of feet. He says that an iambic foot (⏑ –) is made of an arsis and a thesis that stand in a ratio of 1:2, while a trochaic foot (– ⏑) is made of a thesis followed by an arsis, standing in a ratio of 2:1.[25] Aristides refers to the sequence (– ⏑ ⏑) not as a dactyl but as ἀνάπαιστος ἀπὸ μείζονος (anápaistos apò meízonos) (i.e. an anapaest "starting from the greater") and regards it as consisting of a thesis followed by a two-syllable arsis.[26]

In the Seikilos epitaph, a piece of Greek music surviving on a stone inscription from the 1st or 2nd century AD, the notes on the second half of each six-time-unit bar are marked with dots, called stigmai (στιγμαί). According to a treatise known as the Anonymus Bellermanni these dots indicate the arsis of the foot; if so, in this piece the thesis comes first, then the arsis:

| ὅσον – ζῇς, | φαί – νου | μηδὲν – ὅλως | σὺ λυ – ποῦ |

| hóson – zêis, | phaí – nou | mēdèn – hólōs | sù lu – poû |

| thesis — arsis | thesis — arsis | thesis — arsis | thesis — arsis |

According to Tosca Lynch, the song in its conventional transcription of 6/8 rhythm corresponds to the rhythm referred to by ancient Greek rhythmicians as an "iambic dactyl" (δάκτυλος κατ᾽ ἴαμβον (dáktulos kat᾽ íambon) (⏑⏔ ⁝ ⏑⏔) (using the term "dactyl" in the rhythmicians' sense of a foot in which the two parts are of equal length) (cf. Aristides Quintilianus 38.5–6).[27][28]

In one of the fragments of music in the Anonymus Bellermanni treatise itself, likewise in a four-note bar, the second two notes are marked as the arsis. According to Stefan Hagel, it is likely that within the thesis and within the arsis bar divided into two equal parts, there was a further hierarchy with one of the two notes stronger than the other.[29]

In Mesomedes' Hymn to the Sun, on the other hand, which begins with an anapaestic rhythm (⏑⏑– ⏑⏑–), the two short syllables in each case are marked with dots, indicating that the arsis comes first:[30]

| χιο – νοβ | λεφά – ρου | πάτερ – Ἀ | Ἀοῦ – οῦς |

| khio – nob | lephá – rou | páter – A | Aoû – oûs |

| arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis |

In some of the short examples of music in the Anonymus Bellermanni treatise the dots marking the arsis are found not only above notes but also above rests in the music.[31] The exact significance of this is unknown.

Metrical writers' usage

However, writers discussing poetic metre seem to have used the terms arsis and thesis in a different way. Tosca Lynch writes: "Differently from rhythmicians, metricians employed the term arsis to indicate the syllables placed at the beginning of a foot or metrical sequence; in such contexts, the word thesis designated the syllables appearing at the end of the same foot or metrical sequence." (Lynch (2016), p. 506.)

In a metrical dactyl (– ⏑⏑), according to Marius Victorinus and other writers on metre, the first syllable was the arsis, and second and third were the thesis; in an anapaest (⏑⏑ –) the arsis was the first two syllables, and the thesis the third.[32] In the later works of Latin writers on metre, the arsis is invariably considered the first part of the foot (see below).

A Greek work on metre compiled in the 13th century AD, the Anonymus Ambrosianus, refers the words arsis and thesis to a whole line: "Arsis refers to the beginning of a line, thesis to the end."[33]

In word-prosody

Some later grammarians applied the terms arsis and thesis to the prosody of words. Pseudo-Priscian (6th or 7th century AD), appears to have been considering not the metre but the pitch of the voice when he wrote: "In the word natura, when I say natu, the voice is raised and there is arsis; but when ra follows, the voice is lowered and there is thesis. ... The voice itself, which is formed out of words, is assigned to arsis until the accent is completed; what follows the accent is assigned to thesis."[34] Gemistus Pletho, a 14th–15th century Byzantine scholar, seems to adopt this meaning in one passage where he defines arsis as a change from a lower-pitched sound to a higher-pitched one, and thesis the reverse.[35]

Contradicting this, however, Julian of Toledo (Iulianus Toletanus) (7th century AD) writes: "In three-syllable words, if the first syllable has the accent, as in dominus, the arsis claims two syllables and the thesis one; but when the accent is on the penultimate, as in beatus, the arsis has one syllable and the thesis two." Similar statements are found in Terentianus Maurus, Aldhelm, and other grammarians. In disassociating arsis from raised pitch, these writers clearly use the terms in a different way from pseudo-Priscian. In their writings, arsis means the first half of a word, and thesis the second half; if the penultimate syllable in a three-syllable word is accented, the second half is deemed to begin at that point.[36]

Latin and English poetry

In the Latin dactylic hexameter, the strong part of a foot is considered to be the first syllable — always long — and the weak part is what comes after — two short syllables (dactyl: long—short—short) or one long syllable (spondee: long—long). Because Classical poetry was not based on stress, the arsis is often not stressed; only consistent length distinguishes it.

- Arma virumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs...

Of arms and a man I sing, who first from the shores of Troy... — Aeneid 1.1

| Ar — ma vi | rum — que ca | nō — Trō | iae — quī | prī — mus ab | ō — rīs |

| arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis | arsis — thesis |

In English, poetry is based on stress, and therefore arsis and thesis refer to the accented and unaccented parts of a foot.

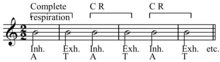

Arsis and thesis in modern music

In measured music, the terms arsis and thesis "are used respectively for unstressed and stressed beats or other equidistant subdivisions of the bar".[37] Thus in music the terms are used in the opposite sense of poetry, with the arsis being the upbeat, or unstressed note preceding the downbeat.

A fugue per arsin et thesin these days generally refers to one where one of the entries comes in with displaced accents (the formerly strong beats becoming weak and vice versa). An example is the bass line at bar 37 of no. 17 Book 2 of Bach's Das Wohltemperierte Clavier. In the past, however, a fugue per arsin et thesin could also mean one where the theme was inverted.

Etymology

Ancient Greek ἄρσις ársis "lifting, removal, raising of foot in beating of time",[38] from αἴρω aírō or ἀείρω aeírō "I lift".[39] The i in aírō is a form of the present tense suffix y, which switched places with the r by metathesis.

Ancient Greek θέσις thésis "setting, placing, composition",[40] from τίθημι títhēmi (from root θε/θη, the/thē, with reduplication) "I put, set, place".[41]

See also

Bibliography

- Beare, W. (1953). "The meaning of ictus as applied to Latin verse". Hermathena No. 81 (May 1953), pp. 29-40.

- Bennett, Charles E. (1898). "What Was Ictus in Latin Prosody?". The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 19, No. 4 (1898), pp. 361-383. Quotes Roman writers on arsis and thesis.

- Lynch, Tosca (2016). "Arsis and Thesis in Ancient Rhythmics and Metrics: A New Approach".Classical Quarterly, 66 (2):491-513.

- Mathiesen, Thomas J. (1985). "Rhythm and Meter in Ancient Greek Music". Music Theory Spectrum, Vol. 7, Time and Rhythm in Music (Spring, 1985), pp. 159-180.

- Moreno, J. Luque; M. del Castillo Herrera (1991). "Arsis–thesis como designaciones de conceptos ajenos a las partes de pie rítmico-métrico". HABIS 22 (1991) 347-360.

- Pearson, Lionel (1990). Aristoxenus: Elementa Rhythmica. (Oxford )

- Rowell, Lewis (1979). "Aristoxenus on Rhythm". Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring, 1979), pp. 63-79.

- Sadie, Stanley (ed.) (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, s.v. Arsis.

- Stephens, L.D. (2012). "Arsis and Thesis". In: Roland Greene, Stephen Cushman et al. (eds.): The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. 4th Edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton, ISBN 978-0-691-13334-8, p. 86.

- Stroh, Wilfried (1990). "Arsis und Thesis oder: wie hat man lateinische Verse gesprochen?" In: Michael von Albrecht, Werner Schubert (Hrsg.): Musik und Dichtung. Neue Forschungsbeiträge. Viktor Pöschl zum 80. Geburtstag gewidmet (= Quellen und Studien zur Musikgeschichte von der Antike bis in die Gegenwart 23). Lang, Frankfurt am Main u. a., ISBN 3-631-41858-2, pp. 87–116.

References

- ^ a b Thurmond, James Morgan (1982). Note Grouping, p.29. ISBN 0-942782-00-3.

- ^ Plural arses: New Oxford English Dictionary (1998); cf. Google ngrams ("arseis" is not found on ngrams, though used by Lynch (2016)).

- ^ "arsis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster..

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989), s.v. Arsis.

- ^ West, M.L. (1982) Greek Metre (Oxford).

- ^ Martin Drury (1986 [1985]), in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature, vol. 1 part 2, p. 203.

- ^ See e.g. Beare (1953); Bennett (1898).

- ^ Rowell (1979), p. 65.

- ^ T.J. Mathiesen, Grove Music Online, s.v. Bacchius.

- ^ Bacchius, Isagoge 98 (Musici Scriptores Graeci, ed. Jan, p. 314, quoted by Pearson, Lionel (1990). Aristoxenus: Elementa Rhythmica. (Oxford ), p. xxiv).

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 495.

- ^ Aristotle probl. 895 B5, quoted by Stroh (1990), p. 95.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 501.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 491.

- ^ Pearson (1990), pp. 10-13.

- ^ Stroh (1990), p. 95.

- ^ Hagel (2008), p. 126.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 503.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 508.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 504.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 495.

- ^ Lynch (2016), pp. 499-500.

- ^ Aristoxenus, 17; Rowell (1979), p. 73.

- ^ Stroh (1990), p. 97.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 508.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 507.

- ^ Lynch, Tosca (2019). "Rhythmics". In Lynch, T. and Rocconi, E. (eds.), A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music, Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 507, note 66.

- ^ Hagel (2008), p. 127.

- ^ Psaroudakes, Stelios "Mesomedes Hymn to the Sun", in Tom Phillips and Armand D'Angour (eds). Music, Text, and Culture in Ancient Greece. Oxford University Press ISBN 9780198794462, p. 123.

- ^ Hagel (2008), p. 129.

- ^ Lynch (2016), pp. 506–7.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 507.

- ^ Lynch (2016), p. 505.

- ^ Moreno & del Castillo (1991), p. 349.

- ^ Moreno & del Castillo (1991), pp. 351–358.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley (ed.) (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, s.v. Arsis.

- ^ ἄρσις. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ ἀείρω in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ θέσις in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ τίθημι in Liddell and Scott.