Ashes to Ashes (David Bowie song)

| "Ashes to Ashes" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

One of the UK artwork variants | ||||

| Single by David Bowie | ||||

| from the album Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) | ||||

| B-side | "Move On" | |||

| Released | 1 August 1980 | |||

| Recorded | February–April 1980 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Songwriter(s) | David Bowie | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| David Bowie singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Ashes to Ashes" on YouTube | ||||

"Ashes to Ashes" is a song by the English musician David Bowie from his 14th studio album, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980). Co-produced by Bowie and Tony Visconti, it was recorded from February to April 1980 in New York and London and features guitar synthesiser played by Chuck Hammer. An art rock, art pop and new wave song led by a flanged piano riff, the lyrics act as a sequel to Bowie's 1969 hit "Space Oddity": the astronaut Major Tom has succumbed to drug addiction and floats isolated in space. Bowie partially based the lyrics on his own experiences with drug addiction throughout the 1970s.

Released as the album's lead single on 1 August 1980, "Ashes to Ashes" became Bowie's second No. 1 single on the UK singles chart and his fastest-selling single. The song's music video, co-directed by Bowie and David Mallet, was at the time the most expensive music video ever made.[1] The solarised video features Bowie as a clown, an astronaut and an asylum inmate, each representing variations on the song's theme, and four members of London's Blitz club, including the singer Steve Strange. Influential on the rising New Romantic movement, commentators have considered it one of Bowie's best videos and among the best videos of all time.

Bowie performed the song only once during 1980 but frequently during his later concert tours. Initially viewed with mixed critical reactions, later reviewers and biographers have considered it one of Bowie's finest songs, particularly praising the unique musical structure. In subsequent decades, the song has appeared on compilation albums and other artists have covered, sampled or used its musical elements for their own songs. The song's namesake was also used for the 2008 BBC series of the same name.

Writing and recording

Backing tracks

The sessions for David Bowie's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) commenced at the Power Station in New York City in February 1980, with production handled by Bowie and longtime collaborator Tony Visconti. The backing tracks for "Ashes to Ashes" were recorded under the working title "People Are Turning to Gold".[2][3][4] The band, as for Bowie's previous four albums, consisted of Carlos Alomar on guitar, George Murray on bass and Dennis Davis on drums. Roy Bittan, a member of Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band who were recording The River (1980) in the adjacent studio, contributed piano while session musician Chuck Hammer played guitar synthesiser.[a][2][3] Hammer, who dubbed his work "guitarchitecture",[4] formerly toured for Lou Reed and was hired by Bowie after he sent tapes of his work to him. Visconti stated that Hammer "would pick a note and out of his amplifier would come a symphonic string section".[5]

For their parts, Alomar played "opaque reggae" and Murray played a funk bassline using a mixture of fingerstyle and slapping.[3][6][7] Davis initially struggled with the ska drumbeat. Bowie played the beat he envisioned for the drummer on a chair and cardboard box, which Davis studied and learned, recording the final take the next day.[5][3] Although desiring a Wurlitzer electronic piano to tape Bittan's piano part, Visconti ran a grand piano through an Eventide Instant Flanger to imitate the sound of one upon learning the real Wurlitzer would take too long to deliver.[5][3] For his parts, Hammer layered four multi-track guitar textures, each given different treatments through the Eventide Harmonizer, which were recorded in the studio's back stairwell to add extra reverb. According to biographer Chris O'Leary, he played "various chord inversions for each chorus section", although Visconti said that "it's the warm string choir you hear on the part that goes, 'I've never done good things, I've never done bad things...'"[5][3]

Vocals and overdubs

The backing tracks were recorded without lyrics or melodies pre-written. Unlike his recent Berlin Trilogy, wherein Bowie wrote lyrics almost immediately after the backing tracks were finished, he wanted to take time writing melodies and lyrics for the Scary Monsters songs.[8] Feeling nostalgic, he had the idea of writing a sequel to his first hit "Space Oddity" (1969), a tale about a fictional astronaut named Major Tom, after re-recording the song in 1979 for The "Will Kenny Everett Make It to 1980?" Show.[3][9] Bowie stated in 1980:[10]

When I originally wrote about Major Tom, I was a very pragmatic and self-opinionated lad that thought he knew all about the great American dream and where it started and where it should stop. Here we had the great blast of American technological know-how shoving this guy up into space, but once he gets there he's not quite sure why he's there. And that's where I left him.

Reconvening in April 1980 at Visconti's own Good Earth Studios in London, Bowie and Visconti recorded the vocal tracks and additional overdubs for the now-titled "Ashes to Ashes".[2][3] Author Peter Doggett states that Bowie originally sang "ashes to ashes" as "ashes to ash" and "funk to funky" as "fun to funky" before settling on the final lines.[11] For overdubs, Visconti added additional percussion and contributions from session keyboardist Andy Clark, who had been introduced to Visconti by Kenny Everett Show "Space Oddity" drummer Andy Duncan. According to biographer Nicholas Pegg, Clark "provided the symphonic sounds" that end the track,[5] while O'Leary says his parts are "a high pitch in the chorus".[3] Upon finishing the track, Visconti recalled: "We love[d] it immensely and knew it was one of the major tracks."[4]

Composition

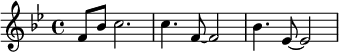

Music

Characterised by commentators as art rock, art pop and new wave;[12][13][14] Pegg describes "Ashes to Ashes" a culmination of Bowie's late 1970s experimental period.[5] With a funk rhythm, a guitar synth-led sound and complex vocal layering,[15][6] author James E. Perone considers it the most musically accessible song on Scary Monsters and on any Bowie album in several years. The author likens Murray's funky bass playing to the plastic soul of Young Americans (1975) and Station to Station (1976).[16]

The song's musical structure is unique and unusual, which Perone argues made it stand out in pop music at the time.[16] The piano riff appears to have a "missing bar". It is a three-bar loop, rather than the more common four-bar loop.

The vocal melody also matches the piano riff through its use of contrasting beats, such as "funk" on the downbeat and "fun-ky" on the off-beat.[3] Visconti called the beat "a mind-bender".[9] Additionally, the vocal melody features contrasting phrasing, meaning the verses consist of unrelated sections, singing through bars ("Major To-om's"), key changes, large vocal register changes and contrasting singing styles.[3][16] O'Leary comments: "It's as if the conductor of an orchestra is also the lead tenor."[3]

"Ashes to Ashes" takes melodic inspiration from "Inchworm" by Danny Kaye, who was one of Bowie's earliest influences. Originating from the 1952 musical film Hans Christian Andersen, Bowie stated in 2003 that the song's chords were some of the first he learned on guitar, calling them "remarkable" and "melancholic": "'Ashes to Ashes' is influenced by that. It's childlike and melancholic in that children's story way."[5] Like "Inchworm", "Ashes to Ashes" contains moves from F to E-flat to close out verses. The song itself is in the key of A-flat major, with the intro and outro featuring "intrusions" of B-flat minor. O'Leary refers to the two bridges as a "series of arcs", as Bowie starts low in his register, rising to high and descending back to low in the same breath. The second verse features dead-pan backing vocals "delay-echoing" the lead vocal.[3][6]

Lyrics

It really is an ode to childhood, if you like, a popular nursery rhyme. It's about space men becoming junkies.[10]

Melancholic and introspective,[17] the song's lyrics act as a sequel to "Space Oddity", which ends with Major Tom alone floating out in space.[9] Eleven years after liftoff,[5] Ground Control receives a message from Major Tom, who has succumbed to drug addiction and increased paranoia following his abandonment to space: "Strung out in heaven's high / hitting an all-time low."[9] Ground Control are not keen on the astronaut's reappearance – "Oh no, don't say it's true" – and pretend that he is fine, in Doggett's words mimicking "government agencies everywhere".[15][11] The astronaut reflects on his life and hopes for the future and wishes he could break free from his "caged psyche".[b][9] His pleas are disregarded by the public, leading him to proclaim that he has "never done good things", has "never done bad things" and "never did anything out of the blue".[15] The song ends with the nursery rhyme lines "My mother said / to get things done / you'd better not mess with Major Tom".[9][15]

Described by the artist as "a story of corruption",[10] Bowie wanted to see where Major Tom ended up in the 1970s:[3]

We come to him 10 years later and find the whole thing has soured, because there was no reason for putting him up there ... [So] the most disastrous thing I could think of is that he finds solace in some kind of heroin-type drug, actually cosmic space feeding him: an addiction. He wants to return to the womb from whence he came.

Regarding the song's drug references, Bowie joked about getting the word "junkie" past the BBC's censors in an interview with NME in September 1980.[10] Comparing "Space Oddity" with "Ashes to Ashes", NPR's Jason Heller evaluated the latter's technological undertones compared to the "psychedelically spacious" former.[9] Writer Tom Ewing wrote that it was as if "Major Tom thought he was starring in an Arthur C. Clarke story and found himself in a Philip K. Dick one by mistake, and the result is oddly magnificent".[3]

Analysis

Reviewers have interpreted "Ashes to Ashes" as commentary on Bowie's own personal struggles with drug addiction throughout the 1970s.[c] Several said the song represents Bowie's reflection and acknowledgement of the past, at the same time offering hopes for the future.[11][16][18] Bowie himself said the Scary Monsters album was an attempt to "accommodate" his "pasts", as "you have to understand why you went through them".[5] The lyrics describe Major Tom as a junkie who has hit "an all-time low". NME editors Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray interpreted the line as a play on the title of Bowie's 1977 album Low, which charted his withdrawal inwards following his drug excesses in the US a short time before, another reversal of Major Tom's original withdrawal "outwards" or towards space.[17]

Biographer David Buckley argues that Bowie offered a comment on his entire career "using a rather sarcastic piece of self-deprecation" with the line "I've never done good things / I've never done bad things / I never did anything out of the blue."[1] Bowie himself said that these three lines "represent a continuing, returning feeling of inadequacy over what I've done."[10] On the artist's future, Buckley interprets the axe line ("Want an axe to break the ice / Wanna come down right now") as his desire to move into less experimental territory and more "normalised" ground.[1] Years later, Bowie said, "I was wrapping up the seventies really for myself, and that seemed a good enough epitaph for it – that we've lost him, he's out there somewhere, we'll leave him be."[5] Heller agreed, arguing that it provided closure for the artist's "most momentous decade".[9]

Release

"Ashes to Ashes" was released in edited form as the lead single from Scary Monsters on 1 August 1980,[3][19] with the catalogue number RCA BOW 6 and the Lodger track "Move On" as the B-side.[20] RCA emphasised the relationship of "Space Oddity" and "Ashes to Ashes" by releasing a nine-minute promo on 12" vinyl in the US titled "The Continuing Story of Major Tom", which segued the former into the latter.[9][5][19] The British single came in three different picture sleeves, each packaged with four different sheets of adhesive stamps, all featuring Bowie in his Pierrot costume from the music video; Pegg says this was RCA adopting "the craze for limited-edition collectables" that pervaded the 7" single market at the time.[5] On Scary Monsters, released on 12 September,[3] "Ashes to Ashes" was sequenced in its full-length form as the fourth track on side one of the original LP, between the title track and "Fashion".[2]

Commercial performance

After years of dwindling commercial fortunes, "Ashes to Ashes" was a return to commercial form for Bowie.[3] Debuting at No. 4 on the UK Singles Chart, the single secured the top spot from ABBA's "The Winner Takes It All" a week later following the music video's broadcast on Top of the Pops. It became Bowie's fastest-selling single up to that point and his second number one single following the 1975 reissue of "Space Oddity".[5][3][1][19]

Compared to the single's strong UK performance, the US release fared worse. With "It's No Game (No. 1)" as the B-side, the US single reached No. 79 on the Cash Box Top 100 chart and No. 101 on the Billboard Bubbling Under the Hot 100 chart.[21] Elsewhere, "Ashes to Ashes" charted at No. 3 in Australia and Norway,[22][23] 4 on the Irish Singles Chart,[24] 6 in Austria, New Zealand and Sweden,[25][26][27] 9 in West Germany,[28] 11 in the Netherlands' Dutch Top 40 and in Switzerland,[29][30] 15 in Belgium Flanders and the Netherlands' Dutch Single Top 100,[31][32] and 35 in Canada.[33] The song also reached No. 14 in France in 2016.[34]

Critical reception

"Ashes to Ashes" initially received mixed reviews from music critics. Amongst positive reviews, a writer for Billboard magazine said the song combines "rock and dance beats" with "tight rock rhythms lay[ing] the groundwork for the nuance-rich melody".[35] In their reviews of the Scary Monsters album, Billboard and The Spokesman-Review's Tom Sowa highlighted "Ashes to Ashes" as one of its best tracks.[36][37]

On the other hand, Deanne Pearson called the song a "strange choice for a single" in Smash Hits, one that was ultimately "not a hit" and should have been left as an album track.[38] Rolling Stone's Debra Rae Cohen described the song as Bowie's "most explicit self-indictment", and one that mirrors "the malaise of the times". Although Cohen found the track's imagery "chilling", she ultimately felt it was hard to see it "as anything but perverse self-aggrandizement".[39] Ronnie Gurr of Record Mirror was negative, finding the song "not in truth a great effort".[40] The magazine ranked it the second best single of 1980, behind "Going Underground" by the Jam,[41] while NME ranked the song the fifth best single of the year.[42]

Music video

The music video for "Ashes to Ashes" was co-directed by Bowie and David Mallet,[43] who had previously directed the videos for Lodger (1979).[44] Filmed at a cost of £250,000,[d][45] it was the most expensive music video ever made at the time and has remained one of the most expensive of all time.[1] Shot in May 1980 over a period of three days,[e] Bowie storyboarded the video himself, planning every shot and dictating the editing process.[5][46] Mallet used the then new Quantel Paintbox to alter the colour palette, rendering the sky black and the ocean pink.[5][9] Writer Michael Shore described Mallet's direction as "deliberately overloaded": "demented, horror-movie camera angles, heavy solarisations, neurotic cuts from supersaturated colour to black-and-white."[44]

Filming locations included Beachy Head and Hastings.[5] Shooting at the beach was Mallet's idea; he later said: "[It is] one of the very rare places you can get right down to the water and there's a cliff towering over you."[46] The crew found an abandoned bulldozer on the beach and were able to contact its owners and employ the vehicle for the shoot.[46] Meanwhile, the "padded cell" and "exploded kitchen" sets were developed from the Kenny Everett Show performance of "Space Oddity", also shot by Mallet, the year prior.[5][47] Similar to Bowie's other music videos, "Ashes to Ashes" does not tell a story, instead being filled with strange images that Buckley compares to a "dreamlike mental state".[44] Discussing the connections between the different locations, Shore states "the stunningly elegant self-referential video-within-video motif, wherein each new sequence is introduced by Bowie holding a postcard-sized video screen displaying the first shot of the next scene".[44]

In the video, Bowie portrays three different characters – a clown, astronaut and asylum inmate – all of whom represent variations of the song's "outsider theme".[f] The black clerical robes of his followers, inspired by The Sound of Music, were designed by Judi Frankland.[46][48] They were worn by members of London's Blitz, a "Bowie-worshipping nightclub" that housed several up-and-coming artists of the New Romantic era, including Steve Strange, a member of Visage.[g][5][44] Strange later told biographer Marc Spitz that his robe kept getting caught in the bulldozer: "That's why I kept doing that move where I pull my arm down. So I wouldn't be crushed."[h][46] Strange's friend Richard Sharah did Bowie's make-up for both the video and the Scary Monsters photo shoot the previous month, while his Italian Pierrot costume was designed by Natasha Korniloff, whose affiliation with the singer dated back to his days as a mime with Lindsay Kemp in 1968.[5][4] The elderly woman who appears at the video's end, acting as Bowie's mother, was not, contrary to popular belief, his actual mother Peggy Jones.[i][5][44]

[It conveyed] some feeling of nostalgia for a future. I've always been hung up on that; it creeps into everything I do, however far away I try to get from it ... The idea of having seen the future, of somewhere we've already been, keeps coming back to me.[5]

In his book Strange Fascination, Buckley states that the video conveys an "Edwardian queasiness", depicting "a world of nostalgia, childhood reminiscence and distant memories".[44] Pegg and Buckley interpret that Bowie's three characters, archetypes that had permeated his songwriting for a decade, act as an "exorcism of his past".[5][44] Bowie himself described the shot of him and his followers walking up the shoreline while the bulldozer trails behind them as symbolising "oncoming violence".[46][49] He also said the followers have religious undertones, "an ominous quality that's rooted quite deeply".[5] Scenes of the singer in a space suit – which suggested a hospital life-support system – and others showing him locked in what appeared to be a padded room, referred to both Major Tom and to Bowie's new, rueful interpretation of him.[5][44] The former scenes were "intentionally" derived from H. R. Giger's designs for the 1979 film Alien.[5]

Live performances

Bowie only performed "Ashes to Ashes" once in 1980, on 3 September for an appearance on NBC's The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. In subsequent decades, Bowie performed the song on the 1983 Serious Moonlight, 1990 Sound+Vision, 1999 Hours, 2002 Heathen, and 2003–2004 A Reality tours.[5] A Serious Moonlight performance, recorded on 12 September 1983, was included on the live album Serious Moonlight (Live '83), released as part of the Loving the Alien (1983–1988) box set in 2018 and separately the following year.[50] The filmed performance also appears on the concert video Serious Moonlight (1984).[51] Bowie's 25 June 2000 performance of the song at the Glastonbury Festival was released in 2018 on Glastonbury 2000,[52] while a recording from a special performance at the BBC Radio Theatre, London, on 27 June 2000 was released on the bonus disc of Bowie at the Beeb.[53][54] Another live recording from the A Reality Tour, recorded in Dublin in November 2003, is included on the accompanying DVD and live album.[55][56] Although O'Leary believes no live performances ever came close to matching the studio recording in quality,[3] Pegg believes "Ashes to Ashes" made "successful transitions" to the stage.[5]

Influence and legacy

It's certainly one of the better songs that I've ever written.[5]

In later decades, reviewers and biographers consider "Ashes to Ashes" one of Bowie's best songs.[5] Praise is given to its musicality and unique structure;[1][16][57] Biographer Paul Trynka, in particular, attributes the song's success to its "melodic inventiveness".[4] Regarding its structure, O'Leary says the track "seems built by a surrealist watchmaker" due to the details present in the mix, deeming it one of Bowie's finest studio recordings.[3] Writing for Consequence of Sound, Nina Corcoran stated the song "makes the most of Bowie's musical creativity" and overall represents "an ode to the '70s".[57] American Songwriter's Jim Beviglia called the song a "dark masterpiece".[15] Rhino Entertainment argued the song predicted the subsequent decade with its "ominous clash of synthesized guitars, hard funk bassline and dissonant guitars".[58]

Some critics analysed the song against Bowie's entire career. O'Leary says that while his career was far from over when the song was released, "Ashes to Ashes" is "his last song" or "the closing chapter that comes midway through the book". He concludes: "Bowie sings himself onstage with a children's rhyme: eternally falling, eternally young."[3] The Guardian's Alexis Petridis said the song represents a moment in his catalogue where "the correct response is to stand back and boggle in awe", because "everything about it – [its] lingering oddness of its sound, its constantly shifting melody and emotional tenor, its alternately self-mythologising and self-doubting lyrics – is perfect".[59] Chris Gerard of PopMatters even considered the track one of Bowie's signature songs.[60]

Artists who have covered "Ashes to Ashes" live or in-studio include Tears for Fears for the 1992 Ruby Trax charity album, Uwe Schmidt, Northern Kings, the Shins, the Mike Flowers Pops and John Wesley Harding.[5] Songs that used musical elements or lyrics from "Ashes to Ashes" include Marilyn Manson's "Apple of Sodom" (1997), Landscape's "Einstein a Go-Go" (1981) and Keane's "Better Than This" (2008).[5] Songs that directly sampled "Ashes to Ashes" include Samantha Mumba's UK top five hit "Body II Body" (2000) and James Murphy's remix of Bowie's 2013 single "Love Is Lost".[61][5] The song was the namesake for the 2008 BBC sequel series to their time-travelling crime drama Life on Mars,[5][62] which itself took its name from another Bowie song "Life on Mars?";[63] an apparition of the clown from the video regularly appeared to the main character Sam Tyler (John Simm) during the show's first series.[64]

The music video has also received praise and recognition as a major influence on the then-rising New Romantic movement.[5] Initially voted by Record Mirror's readers as the best music video of 1980, together with "Fashion",[41] Rolling Stone placed it at number 44 in their list of the 100 best music videos of all time in 2021. Discussing the video's influence upon its release, Andy Greene wrote: "MTV came onto the airwaves exactly one year later, and it would give rise to a whole new generation of Bowie imitators, but none of them could compete with the real deal."[45] Dig! website also included the visual in their list of 20 essential clips of the 1980s. Luke Edwards argued that the video "truly captured the spirit of the MTV age" before the channel's golden era.[13]

Commentators hail the video as not only one of Bowie's finest, but one of the medium's high points.[1][46] Considered "the defining early music video" by Buckley, and "one of the most significant and influential of the age" by Dave Thompson,[44][19] its techniques and effects influenced videos of artists including Adam Ant, Duran Duran and the Cure.[5] Pegg argues the visual "define[d] rock video for the early 1980s",[5] while Heller contended it proved music videos were "viable promotional investments".[9] Videos that later mimicked or took appropriation from the "Ashes to Ashes" video included Peter Gabriel's "Shock the Monkey" (1982), Erasure's "Chorus" (1991) and Marilyn Manson's "The Dope Show" (1998).[5]

"Ashes to Ashes", in both its single edit and full-length forms, has made appearances on compilation albums. The single edit is included on Changestwobowie (1981),[65] Best of Bowie (2002),[66] The Platinum Collection (2006),[67] Nothing Has Changed (2014) and Legacy (The Very Best of David Bowie) (2016),[68][69] while the album version is included on the Sound + Vision box set (1989),[70] Changesbowie (1990) and The Singles Collection (1993).[71][72] The single edit was also included on Re:Call 3, part of the A New Career in a New Town (1977–1982) compilation, in 2017.[73] An unreleased extended version, allegedly 13-minutes long and featuring additional verses, a longer fade-out and a synthesiser solo, is rumoured to exist, although a 12-minute version that appeared on bootlegs was fake, simply repeating and splicing the verses.[5][19] In 2020, Visconti said that no additional verses were recorded nor is he aware of any other versions of the song existing.[74]

Following Bowie's death in January 2016, Rolling Stone named "Ashes to Ashes" one of the 30 most essential songs of the artist's catalogue. The magazine wrote: "As offbeat as the song was, it's a testament to Bowie's art-pop genius that 'Ashes to Ashes' became a huge international hit."[75] The song has appeared on lists of Bowie's greatest songs by The Telegraph,[76] The Guardian (No. 2), behind "Sound and Vision" (1977),[59] Digital Spy (No. 3),[77] Far Out and Uncut (No. 6),[78][79] Smooth Radio (No. 7),[80] NME (No. 9),[81] Mojo (No. 10) and Consequence of Sound (No. 30).[57][82] In 2016, Ultimate Classic Rock placed the single at number 10 in a list ranking every Bowie single from worst to best.[83] Two years later, NME readers voted it Bowie's third best track, behind "All the Young Dudes" (1972) and "Life on Mars?" (1971).[84]

Personnel

According to Chris O'Leary:[3]

- David Bowie – lead and backing vocal

- Chuck Hammer – Roland GR-500 guitar synthesiser

- Carlos Alomar – rhythm guitar

- Andy Clark – Minimoog, Yamaha CS-80 synthesiser

- Roy Bittan – flanged piano

- George Murray – bass

- Dennis Davis – drums

- Tony Visconti – shaker, other percussion

Technical

- David Bowie – producer

- Tony Visconti – producer, engineer

- Larry Alexander – engineer

- Jeff Hendrickson – engineer

Charts

Weekly charts

| Chart (1980–1981) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[85][22] | 3 |

| Austria (Ö3 Austria Top 40)[25] | 6 |

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Flanders)[31] | 15 |

| Canada Top Singles (RPM)[33] | 35 |

| Ireland (IRMA)[24] | 4 |

| Netherlands (Dutch Top 40)[29] | 11 |

| Netherlands (Single Top 100)[32] | 15 |

| France (IFOP)[86] | 1 |

| New Zealand (Recorded Music NZ)[26] | 6 |

| Norway (VG-lista)[23] | 3 |

| Portugal (AFP)[87] | 2 |

| Sweden (Sverigetopplistan)[27] | 6 |

| Switzerland (Schweizer Hitparade)[30] | 11 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[88] | 1 |

| US Bubbling Under Hot 100 (Billboard)[21] | 101 |

| US Disco Top 100 (Billboard)[89] | 21 |

| US Cash Box Top 100 Singles[21] | 79 |

| West Germany (GfK)[28] | 9 |

| Chart (2016) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| France (SNEP)[34] | 14 |

Year-end charts

| Chart (1980) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[85] | 25 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[90] | 14 |

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[91] | Gold | 400,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

- ^ King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, who contributed guitar to the rest of Scary Monsters, does not appear on "Ashes to Ashes".

- ^ The line about an axe breaking ice was a paraphrased manifesto from a letter by Franz Kafka that read: "A book must be an ice-axe to break the frozen seas inside us."[11]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[3][5][11][1][18]

- ^ In The Complete David Bowie, Pegg lists the cost as £25,000.[5]

- ^ Mallet recalled the "norm" for a video at the time was one day.[43]

- ^ According to Buckley, the Pierrot figure was based on a commedia dell'arte Renaissance costume.[44]

- ^ The three others — Elise Brazier, Judith Frankland and Darla Jane Gilroy[43][45] — were handpicked by Strange. Blitz regular Marilyn and Bowie fan George O'Dowd, later famous as Boy George, were passed over for appearances.

- ^ Bowie liked the move and incorporated it into the videos for his next single, "Fashion", "Loving the Alien" (1984) and "Dancing in the Street" (1985).[5]

- ^ The elderly woman some interpreted as a response to the 1975 NME interview with Bowie's mother, Peggy Jones, which revealed embarrassing personal details between her and the artist; Bowie had repaired his relationship with his mother in the years following the article's publication and before recording "Ashes to Ashes".

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Buckley 2005, pp. 316–317.

- ^ a b c d Pegg 2016, pp. 397–401.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x O'Leary 2019, chap. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Trynka 2011, pp. 354–355.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao Pegg 2016, pp. 27–30.

- ^ a b c Welch 1999, p. 136.

- ^ Lindsay, Matthew (7 September 2021). "Making David Bowie: Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)". Classic Pop. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 314–316.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Heller, Jason (6 October 2017). "How 'Ashes To Ashes' Put The First Act of David Bowie's Career to Rest". NPR. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e MacKinnon, Angus (13 September 1980). "The Future Isn't What It Used to Be". NME. pp. 31–37. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via bowiegoldenyears.com.

- ^ a b c d e Doggett 2012, pp. 372–374.

- ^ Lynch, Joe (11 January 2016). "10 Brilliantly Bizarre David Bowie Videos". Billboard. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ a b Edwards, Luke (11 November 2022). "Best 80s Music Videos: 20 Essential Clips From MTV's Golden Era". Dig!. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Comer, M. Tye (15 May 2000). "Pop Artificielle – LB". CMJ New Music Report. 62 (666). CMJ: 20. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Beviglia, Jim (2020). "Behind the Song: David Bowie, 'Ashes to Ashes'". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Perone 2007, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 109–116.

- ^ a b Leas, Ryan (11 September 2020). "David Bowie's 'Scary Monsters' at 40: The Hidden Classic of His Career". Stereogum. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson, Dave. "'Ashes to Ashes' – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ O'Leary 2019, Partial Discography.

- ^ a b c Whitburn 2015, p. 57.

- ^ a b Smith, Danyel, ed. (1980). "Billboard 25 october 1980". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes". VG-lista. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Ashes to ashes in Irish Chart". IRMA. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2013. 3rd result when searching "Ashes to ashes"

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Nederlandse Top 40 – David Bowie" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Singles: Issue 0274." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Top Single Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 13 September 1980. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 20 September 1980. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Sowa, Tom (31 October 1980). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (RCA AQLI 3647)". The Spokesman-Review. p. 53. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Pearson, Deanne (7 August 1980). "Reviews – Singles (David Bowie – 'Ashes to Ashes')". Smash Hits. 2 (16): 27.

- ^ Cohen, Debra Rae (25 December 1980). "Scary Monsters". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Gurr, Ronnie (2 August 1980). "Singles Reviews" (PDF). Record Mirror. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b "Poll 1980 Results" (PDF). Record Mirror. 10 January 1981. pp. 16–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "NME's best albums and tracks of 1980". NME. 10 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Jones 2017, pp. 286–288.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Buckley 2005, pp. 304–307.

- ^ a b c Greene, Andy (30 July 2021). "The 100 Best Music Videos of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Spitz 2009, pp. 309–311.

- ^ Male, Andrew (23 July 2013). "David Bowie and Kenny Everett's 'Space Oddity'". Mojo. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ Johnson, David (4 October 2009). "Spandau Ballet, the Blitz kids and the Birth of the New Romantics". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Malins, Steve (2007). "Meeting the New Romantics". Mojo. 60 Years of Bowie. p. 78.

- ^ "Loving the Alien breaks out due February". David Bowie Official Website. 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 640–641.

- ^ Collins, Sean T. (5 December 2018). "David Bowie: Glastonbury 2000 Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 633.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Bowie at the Beeb: The Best of the BBC Radio Sessions 68–72 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 573.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "A Reality Tour – Davis Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "David Bowie's Top 70 Songs". Consequence of Sound. 8 January 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ "Single Stories: David Bowie, 'Ashes To Ashes'". Rhino Entertainment. 23 August 2022. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b Petridis, Alexis (19 March 2020). "David Bowie's 50 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Gerard, Chris (12 October 2017). "Filtered Through the Prism of David Bowie's Quixotic Mind: 'A New Career in a New Town'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Reviews: Single Reviews". Music Week. 7 October 2000. p. 26.

- ^ "Life after Mars". The Guardian. 7 January 2008. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 163.

- ^ Curley, John (10 May 2010). "Ashes to Ashes (and its great early '80s soundtrack) returns to BBC America". Goldmine. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Dave. "Changestwobowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Best of Bowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Monger, James Christopher. "The Platinum Collection – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Sawdey, Evan (10 November 2017). "David Bowie: Nothing Has Changed". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Monroe, Jazz (28 September 2016). "David Bowie Singles Collection Bowie Legacy Announced". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Sound + Vision boxset repack press release". David Bowie Official Website. 26 July 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Changesbowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Singles: 1969–1993 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "A New Career In A New Town (1977–1982) – David Bowie Latest News". David Bowie Official Website. 22 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Exclusive Q&A with Tony Visconti". David Bowie News | Celebrating the Genius of David Bowie. 11 August 2020. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "David Bowie: 30 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ "David Bowie's 20 greatest songs". The Telegraph. 10 January 2021. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Nissim, Mayer (11 January 2016). "David Bowie 1947–2016: 'Life on Mars' is named Bowie's greatest ever song in reader poll". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Whatley, Jack; Taylor, Tom (8 January 2022). "David Bowie's 50 greatest songs of all time". Far Out. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "David Bowie's 30 best songs". Uncut. No. 133. March 2008. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Eames, Tom (26 June 2020). "David Bowie's 20 greatest ever songs, ranked". Smooth Radio. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Barker, Emily (8 January 2018). "David Bowie's 40 greatest songs – as decided by NME and friends". NME. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (February 2015). "David Bowie – The 100 Greatest Songs". Mojo. No. 255. p. 80.

- ^ "Every David Bowie Single Ranked". Ultimate Classic Rock. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Sarah (8 January 2018). "20 best David Bowie tracks – as voted by you". NME. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b "National Top 100 Singles for 1980". Kent Music Report. 5 January 1981. Retrieved 17 January 2022 – via Imgur.

- ^ "Ashes to ashes in French Chart" (in French). IFOP. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ "David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes". AFP Top 100 Singles. Retrieved 6 Oct 2023.

- ^ "1980 Top 40 Official UK Singles Archive – 23rd August 1980". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "David Bowie – Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "Chart File". Record Mirror. 21 March 1981. p. 37.

- ^ "British single certifications – David Bowie – Ashes to Ashes". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

Sources

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York City: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- Jones, Dylan (2017). David Bowie: A Life. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-0-45149-783-3.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2018. London: Repeater. ISBN 978-1-91224-830-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.

- Welch, Chris (1999). David Bowie: We Could Be Heroes: The Stories Behind Every David Bowie Song. Boston: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-209-2.

- Whitburn, Joel (2015). The Comparison Book. Menonomee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. ISBN 978-0-89820-213-7.

- 1980 singles

- 1980 songs

- David Bowie songs

- British new wave songs

- RCA Records singles

- Sequel songs

- Song recordings produced by David Bowie

- Song recordings produced by Tony Visconti

- Songs about cocaine

- Songs written by David Bowie

- UK singles chart number-one singles

- Music videos directed by David Bowie

- Major Tom

- Music videos directed by David Mallet (director)