Cambodian Civil War

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

The Cambodian Civil War (Khmer: សង្គ្រាមស៊ីវិលកម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: Sângkréam Sivĭl Kâmpŭchéa) was a civil war in Cambodia fought between the forces of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (known as the Khmer Rouge, supported by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong) against the government forces of the Kingdom of Cambodia and, after October 1970, the Khmer Republic, which had succeeded the kingdom after a coup (both supported by the United States and South Vietnam).

The struggle was complicated by the influence and actions of the allies of the two warring sides. North Vietnam's People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) involvement was designed to protect its Base Areas and sanctuaries in eastern Cambodia, without which it would have been harder to pursue its military effort in South Vietnam. Their presence was at first tolerated by Prince Sihanouk, the Cambodian head of state, but domestic resistance combined with China and North Vietnam continuing to provide aid to the anti-government Khmer Rouge alarmed Sihanouk and caused him to go to Moscow to request the Soviets rein in the behavior of North Vietnam.[6] The deposition of Sihanouk by the Cambodian National Assembly in March 1970, following wide scale protests in the capital against the presence of PAVN troops in the country, put a pro-American government in power (later declared the Khmer Republic) which demanded that the PAVN leave Cambodia. The PAVN refused and, at the request of the Khmer Rouge, promptly invaded Cambodia in force.

Between March and June 1970, the North Vietnamese captured most of the northeastern third of the country in engagements with the Cambodian army. The North Vietnamese turned over some of their conquests and provided other assistance to the Khmer Rouge, thus empowering what was at the time a small guerrilla movement.[7] The Cambodian government hastened to expand its army to combat the North Vietnamese and the growing power of the Khmer Rouge.[8]

The U.S. was motivated by the desire to buy time for its withdrawal from Southeast Asia, to protect its ally in South Vietnam, and to prevent the spread of communism to Cambodia. American, South Vietnamese, and North Vietnamese forces directly participated in the fighting. The U.S. assisted the central government with massive U.S. aerial bombing campaigns and direct material and financial aid, while the North Vietnamese kept soldiers on the lands that they had previously occupied and occasionally engaged the Khmer Republic army in ground combat.

After five years of savage fighting, the Republican government was defeated on 17 April 1975 when the victorious Khmer Rouge proclaimed the establishment of Democratic Kampuchea. The war caused a refugee crisis in Cambodia with two million people—more than 25 percent of the population—displaced from rural areas into the cities, especially Phnom Penh which grew from about 600,000 in 1970 to an estimated population of nearly 2 million by 1975.

Children were often being persuaded or forced to commit atrocities during the war.[9] The Cambodian government estimated that more than 20 percent of the property in the country had been destroyed during the war.[10] In total, an estimated 275,000–310,000 people were killed as a result of the war.

The conflict was part of the Second Indochina War (1955–1975) which also consumed the neighboring Laos, South Vietnam, and North Vietnam individually referred to as the Laotian Civil War and the Vietnam War respectively. The Cambodian civil war led to the Cambodian genocide, one of the bloodiest in history.

Setting the stage (1965–1970)

Background

During the early-to-mid-1960s, Prince Norodom Sihanouk's policies had protected his nation from the turmoil that engulfed Laos and South Vietnam.[11] Neither the People's Republic of China (PRC) nor North Vietnam disputed Sihanouk's claim to represent "progressive" political policies and the leadership of the prince's domestic leftist opposition, the Pracheachon Party, had been integrated into the government.[12] On 3 May 1965, Sihanouk broke diplomatic relations with the U.S., ended the flow of American aid, and turned to the PRC and the Soviet Union for economic and military assistance.[12]

By the late 1960s, Sihanouk's delicate domestic and foreign policy balancing act was beginning to go awry. In 1966, an agreement was struck between the prince and the Chinese, allowing the presence of large-scale PAVN and Viet Cong troop deployments and logistical bases in the eastern border regions.[13] He had also agreed to allow the use of the port of Sihanoukville by communist-flagged vessels delivering supplies and material to support the PAVN/Viet Cong military effort in South Vietnam.[14] These concessions made questionable Cambodia's neutrality, which had been guaranteed by the Geneva Conference of 1954.

Sihanouk was convinced that the PRC, not the U.S., would eventually control the Indochinese Peninsula and that "our interests are best served by dealing with the camp that one day will dominate the whole of Asia – and coming to terms before its victory – in order to obtain the best terms possible."[13]

During the same year, however, he allowed his pro-American minister of defense, General Lon Nol, to crack down on leftist activities, crushing the Pracheachon by accusing its members of subversion and subservience to Hanoi.[15] Simultaneously, Sihanouk lost the support of Cambodia's conservatives as a result of his failure to come to grips with the deteriorating economic situation (exacerbated by the loss of rice exports, most of which went to the PAVN/Viet Cong) and with the growing communist military presence.[a]

On 11 September 1966, Cambodia held its first open election. Through manipulation and harassment the conservatives won 75 percent of the seats in the National Assembly to Sihanouk's surprise.[16][17] Lon Nol was chosen by the right as prime minister and, as his deputy, they named Prince Sirik Matak; an ultraconservative member of the Sisowath branch of the royal clan and long-time enemy of Sihanouk. In addition to these developments and the clash of interests among Phnom Penh's politicized elite, social tensions created a favorable environment for the growth of a domestic communist insurgency in the rural areas.[18]

Revolt in Battambang

The prince then found himself in a political dilemma. To maintain the balance against the rising tide of the conservatives, he named the leaders of the very group he had been oppressing as members of a "counter-government" that was meant to monitor and criticize Lon Nol's administration.[19] One of Lon Nol's first priorities was to fix the ailing economy by halting the illegal sale of rice to the communists. Soldiers were dispatched to the rice-growing areas to forcibly collect the harvests at gunpoint, and they paid only the low government price. There was widespread unrest, especially in rice-rich Battambang Province, an area long-noted for the presence of large landowners, great disparity in wealth, and where the communists still had some influence.[20][21]

On 11 March 1967, while Sihanouk was out of the country in France, a rebellion broke out in the area around Samlaut in Battambang, when enraged villagers attacked a tax collection brigade. With the probable encouragement of local communist cadres, the insurrection quickly spread throughout the whole region.[22] Lon Nol, acting in the prince's absence (but with his approval), responded by declaring martial law.[19] Hundreds of peasants were killed and whole villages were laid waste during the repression.[23] After returning home in March, Sihanouk abandoned his centrist position and personally ordered the arrest of Khieu Samphan, Hou Yuon, and Hu Nim, the leaders of the "counter government", all of whom escaped into the northeast.[24]

Simultaneously, Sihanouk ordered the arrest of Chinese middlemen involved in the illegal rice trade, thereby raising government revenues and placating the conservatives. Lon Nol was forced to resign, and, in a typical move, the prince named new leftists to the government to balance the conservatives.[24] The immediate crisis had passed, but it engendered two consequences. First, it drove thousands of new recruits into the arms of the hard-line maquis of the Cambodian Communist Party (which Sihanouk labelled the Khmers rouges ("Red Khmers")). Second, for the peasantry, the name of Lon Nol became associated with ruthless repression throughout Cambodia.[25]

Communist regroupment

While the 1967 insurgency had been unplanned, the Khmer Rouge tried, without much success, to organize a more serious revolt during the following year. The prince's decimation of the Prachea Chon and the urban communists had, however, cleared the field of competition for Saloth Sar (also known as Pol Pot), Ieng Sary, and Son Sen—the Maoist leadership of the maquisards.[26] They led their followers into the highlands of the northeast and into the lands of the Khmer Loeu, a tribal people who were hostile to both the lowland Khmers and the central government. For the Khmer Rouge, who still lacked assistance from the North Vietnamese, it was a period of regroupment, organization, and training. Hanoi basically ignored its Chinese-sponsored allies, and the indifference of their "fraternal comrades" to their insurgency between 1967 and 1969 would make an indelible impression on the Khmer Rouge leadership.[27][28]

On 17 January 1968, the Khmer Rouge launched their first offensive. It was aimed more at gathering weapons and spreading propaganda than in seizing territory since, at that time, the adherents of the insurgency numbered no more than 4,000–5,000.[29][30] During the same month, the communists established the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea as the military wing of the party. As early as the end of the Battambang revolt, Sihanouk had begun to reevaluate his relationship with the communists.[31] His earlier agreement with the Chinese had availed him nothing. They had not only failed to restrain the North Vietnamese, but they had actually involved themselves (through the Khmer Rouge) in active subversion within his country.[22]

At the suggestion of Lon Nol (who had returned to the cabinet as defense minister in November 1968) and other conservative politicians, on 11 May 1969, the prince welcomed the restoration of normal diplomatic relations with the U.S. and created a new Government of National Salvation with Lon Nol as his prime minister.[6] He did so "in order to play a new card, since the Asian communists are already attacking us before the end of the Vietnam War."[32] Besides, PAVN and the Viet Cong would make very convenient scapegoats for Cambodia's ills, much more so than the minuscule Khmer Rouge, and ridding Cambodia of their presence would solve many problems simultaneously.[33]

Operation Menu and Operation Freedom Deal

Although the U.S. had been aware of the PAVN/Viet Cong sanctuaries in Cambodia since 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson had chosen not to attack them due to possible international repercussions and his belief that Sihanouk could be convinced to alter his policies.[34] Johnson did, however, authorize the reconnaissance teams of the highly classified Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group (SOG) to enter Cambodia and gather intelligence on the Base Areas in 1967.[35] The election of Richard Nixon in 1968 and the introduction of his policies of gradual U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam and the Vietnamization of the conflict there, changed everything.[citation needed]

On 18 March 1969, on secret orders from Nixon and Henry Kissinger, the U.S. Air Force carried out the bombing of Base Area 353 (in the Fishhook region opposite South Vietnam's Tây Ninh Province) by 59 B-52 Stratofortress bombers. This strike was the first in a series of attacks on the sanctuaries that lasted until May 1970. During Operation Menu, the Air Force conducted 3,875 sorties and dropped more than 108,000 tons of ordnance on the eastern border areas.[36] Only five high-ranking congressional officials were informed of the bombing.[37]

After the event, it was claimed by Nixon and Kissinger that Sihanouk had given his tacit approval for the raids, but this is dubious.[38] Sihanouk told U.S. diplomat Chester Bowles on 10 January 1968, that he would not oppose American "hot pursuit" of retreating North Vietnamese troops "in remote areas [of Cambodia]," provided that Cambodians were unharmed. Kenton Clymer notes that this statement "cannot reasonably be construed to mean that Sihanouk approved of the intensive, ongoing B-52 bombing raids ... In any event, no one asked him. ... Sihanouk was never asked to approve the B-52 bombings, and he never gave his approval."[39] During the course of the Menu bombings, Sihanouk's government formally protested "American violation[s] of Cambodian territory and airspace" at the United Nations on over 100 occasions, although it "specifically protested the use of B-52s" only once, following an attack on Bu Chric in November 1969.[40][41]

Operation Freedom Deal followed Operation Menu. Under Freedom Deal, from 19 May 1970 to 15 August 1973, U.S. bombing of Cambodia extended over the entire eastern one-half of the country and was especially intense in the heavily populated southeastern one-quarter of the country, including a wide ring surrounding the largest city of Phnom Penh. In large areas, according to maps of U.S. bombing sites, it appears that nearly every square mile of land was hit by bombs.[42]

The effectiveness of the U.S. bombing on the Khmer Rouge and the death toll of Cambodian civilians is disputed. With limited data, the range of Cambodian deaths caused by U.S. bombing may be between 30,000 and 150,000 Cambodian civilians and Khmer Rouge fighters.[42][43] Another impact of the U.S. bombing and the Cambodian civil war was to destroy the homes and livelihood of many people. This was a heavy contributor to the refugee crisis in Cambodia.[10]

It has been argued that the U.S. intervention in Cambodia contributed to the eventual seizure of power by the Khmer Rouge, that grew from 4,000 in number in 1970 to 70,000 in 1975.[44] This view has been disputed,[45][46][47] with documents uncovered from the Soviet archives revealing that the North Vietnamese offensive in Cambodia in 1970 was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge following negotiations with Nuon Chea.[8] It has also been argued that U.S. bombing was decisive in delaying a Khmer Rouge victory.[47][48][49][50] Victory in Vietnam, the official war history of the People's Army of Vietnam, candidly states that the communist insurgency in Cambodia had already increased from "ten guerrilla teams" to several tens of thousands of fighters only two months after the North Vietnamese invasion in April 1970, as a direct result of the PAVN seizing 40% of the country, handing it over to the communist insurgents, and then actively supplying and training the insurgents.[51]

Overthrow of Sihanouk (1970)

Overthrow

While Sihanouk was out of the country on a trip to France, anti-Vietnamese rioting (which was semi-sponsored by the government) took place in Phnom Penh, during which the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong embassies were sacked.[52][53] In the prince's absence, Lon Nol did nothing to halt these activities.[54] On 12 March, the prime minister closed the port of Sihanoukville to the North Vietnamese and issued an impossible ultimatum to them. All PAVN/Viet Cong forces were to withdraw from Cambodian soil within 72 hours (on 15 March) or face military action.[55]

Sihanouk, hearing of the turmoil, headed for Moscow and Beijing in order to demand that the patrons of PAVN and the Viet Cong exert more control over their clients.[6] On 18 March 1970, Lon Nol requested that the National Assembly vote on the future of the prince's leadership of the nation. Sihanouk was ousted from power by a vote of 86–3.[56][57] Cheng Heng became president of the National Assembly, while Prime Minister Lon Nol was granted emergency powers. Sirik Matak retained his post as deputy prime minister. The new government emphasized that the transfer of power had been totally legal and constitutional and it received the recognition of most foreign governments. There have been, and continue to be, accusations that the U.S. government played some role in the overthrow of Sihanouk, but conclusive evidence has never been found to support them.[58]

The majority of middle-class and educated Khmers had grown weary of the prince and welcomed the change of government.[59] They were joined by the military, for whom the prospect of the return of American military and financial aid was a cause for celebration.[60] Within days of his deposition, Sihanouk, now in Beijing, broadcast an appeal to the people to resist the usurpers.[6] Demonstrations and riots occurred (mainly in areas contiguous to PAVN/Viet Cong controlled areas), but no nationwide groundswell threatened the government.[61] In one incident at Kampong Cham on 29 March, however, an enraged crowd killed Lon Nol's brother, Lon Nil, tore out his liver, and cooked and ate it.[60] An estimated 40,000 peasants then began to march on the capital to demand Sihanouk's reinstatement. They were dispersed, with many casualties, by contingents of the armed forces.[citation needed]

Massacre of the Vietnamese

Most of the population, urban and rural, took out their anger and frustrations on the nation's Vietnamese population. Lon Nol's call for 10,000 volunteers to boost the manpower of Cambodia's poorly equipped, 30,000-man army, managed to swamp the military with over 70,000 recruits.[62] Rumours abounded concerning a possible PAVN offensive aimed at Phnom Penh itself. Paranoia flourished and this set off a violent reaction against the nation's 400,000 ethnic Vietnamese.[60]

Lon Nol hoped to use the Vietnamese as hostages against PAVN/Viet Cong activities, and the military set about rounding them up into detention camps.[60] That was when the killing began. In towns and villages all over Cambodia, soldiers and civilians sought out their Vietnamese neighbors in order to murder them.[63] On 15 April, the bodies of 800 Vietnamese floated down the Mekong River and into South Vietnam.[citation needed]

The South Vietnamese, North Vietnamese, and the Viet Cong all harshly denounced these actions.[64] Significantly, no Cambodians—including the Buddhist community—condemned the killings. In his apology to the Saigon government, Lon Nol stated that "it was difficult to distinguish between Vietnamese citizens who were Viet Cong and those who were not. So it is quite normal that the reaction of Cambodian troops, who feel themselves betrayed, is difficult to control."[65]

FUNK and GRUNK

From Beijing, Sihanouk proclaimed that the government in Phnom Penh was dissolved and his intention to create the Front uni national du Kampuchéa (National United Front of Kampuchea) or FUNK. Sihanouk later said "I had chosen not to be with either the Americans or the communists, because I considered that there were two dangers, American imperialism and Asian communism. It was Lon Nol who obliged me to choose between them."[60]

The North Vietnamese reacted to the political changes in Cambodia by sending Premier Phạm Văn Đồng to meet Sihanouk in China and recruit him into an alliance with the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot was also contacted by the Vietnamese who now offered him whatever resources he wanted for his insurgency against the Cambodian government. Pol Pot and Sihanouk were actually in Beijing at the same time, but the Vietnamese and Chinese leaders never informed Sihanouk of the presence of Pol Pot or allowed the two men to meet.[66]

Shortly after, Sihanouk issued an appeal by radio to the people of Cambodia to rise up against the government and support the Khmer Rouge. In doing so, Sihanouk lent his name and popularity in the rural areas of Cambodia to a movement over which he had little control.[66] In May 1970, Pol Pot finally returned to Cambodia and the pace of the insurgency greatly increased. After Sihanouk showed his support for the Khmer Rouge by visiting them in the field, their ranks swelled from 6,000 to 50,000 fighters.[citation needed]

The prince then allied himself with the Khmer Rouge, the North Vietnamese, the Laotian Pathet Lao and the Viet Cong, throwing his personal prestige behind the communists. On 5 May, the actual establishment of FUNK and of the Gouvernement royal d'union nationale du Kampuchéa or GRUNK (Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea), was proclaimed. Sihanouk assumed the post of head of state, appointing Penn Nouth, one of his most loyal supporters, as prime minister.[60]

Khieu Samphan was designated deputy prime minister, minister of defense, and commander in chief of the GRUNK armed forces (though actual military operations were directed by Pol Pot). Hu Nim became minister of information, and Hou Yuon assumed multiple responsibilities as minister of the interior, communal reforms, and cooperatives. GRUNK claimed that it was not a government-in-exile since Khieu Samphan and the insurgents remained inside Cambodia. Sihanouk and his loyalists remained in China, although the prince did make a visit to the "liberated areas" of Cambodia, including Angkor Wat, in March 1973. These visits were used mainly for propaganda purposes and had no real influence on political affairs.[67]

For Sihanouk, this proved to be a marriage of convenience that was spurred on by his thirst for revenge against those who had betrayed him.[68][69] For the Khmer Rouge, it was a means to greatly expand the appeal of their movement. Peasants, motivated by loyalty to the monarchy, gradually rallied to the GRUNK cause.[70] The personal appeal of Sihanouk and widespread U.S. aerial bombardment helped recruitment. This task was made even easier for the communists after 9 October 1970, when Lon Nol abolished the loosely federalist monarchy and proclaimed the establishment of a centralized Khmer Republic.[71]

The GRUNK was soon caught between the competing Communist powers: North Vietnam, China and the Soviet Union. During the visits that Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and Sihanouk paid to North Korea in April and June 1970, respectively, they called for the establishment of a "united front of the five revolutionary Asian countries" (China, North Korea, North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, the last being represented by the GRUNK). While the North Korean leaders enthusiastically welcomed the plan, it soon foundered on Hanoi's opposition. Having realized that such a front would exclude the Soviet Union and implicitly challenge the hegemonic role that the DRV had arrogated to itself in Indochina, the North Vietnamese leaders declared that all communist states should join forces against "American imperialism."[72]

Indeed, the issue of Vietnamese versus Chinese hegemony over Indochina greatly influenced the attitude Hanoi adopted towards Moscow in the early and mid-1970s. During the Cambodian civil war, the Soviet leaders, ready to acquiesce in Hanoi's dominance over Laos and Cambodia, actually insisted on sending their aid shipments to the Khmer Rouge through the DRV, whereas China firmly rebuffed Hanoi's proposal that Chinese aid to Cambodia be sent via North Vietnam. Facing Chinese competition and Soviet acquiescence, the North Vietnamese leaders found the Soviet option more advantageous to their interests, a calculation that played a major role in the gradual pro-Soviet shift in Hanoi's foreign policies.[72]

Widening war (1970–1971)

North Vietnamese offensive in Cambodia

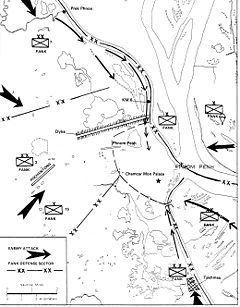

In the wake of the coup, Lon Nol did not immediately launch Cambodia into war. He appealed to the international community and to the United Nations in an attempt to gain support for the new government and condemned violations of Cambodia's neutrality "by foreign forces, whatever camp they come from."[73] His hope for continued neutralism availed him no more than it had Sihanouk. On 29 March 1970, the North Vietnamese had taken matters into their own hands and launched an offensive against the now renamed Forces Armées Nationales Khmères or FANK (Khmer National Armed Forces) with documents uncovered from the Soviet archives revealing that the offensive was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge following negotiations with Nuon Chea.[8] The North Vietnamese overran most of northeastern Cambodia by June 1970.[7]

The North Vietnamese invasion completely changed the course of the civil war. Cambodia's army was mauled, lands containing nearly half of the Cambodian population were conquered and handed over to the Khmer Rouge and North Vietnam now took an active role in supplying and training the Khmer Rouge. All of this resulted in the Cambodian government being greatly weakened and the insurgents multiplying several fold in size over the course of a few weeks. As noted in the official Vietnamese war history, "our troops helped our Cambodian friends to completely liberate five provinces with a total population of three million people... our troops also helped our Cambodian friends train cadre and expand their armed forces. In just two months the armed forces of our Cambodian allies grew from ten guerrilla teams to nine battalions and 80 companies of full-time troops with a total strength of 20,000 soldiers, plus hundreds of guerrilla squads and platoons in the villages."[74]

On 29 April 1970, South Vietnamese and U.S. units unleashed a limited, multi-pronged Cambodian Campaign that Washington hoped would solve three problems: First, it would provide a shield for the American withdrawal from Vietnam (by destroying the PAVN logistical system and killing enemy troops) in Cambodia; second, it would provide a test for the policy of Vietnamization; third, it would serve as a signal to Hanoi that Nixon meant business.[75] Despite Nixon's appreciation of Lon Nol's position, the Cambodian leader was not even informed in advance of the decision to send troops into his country. He learned about it only after it had begun from the head of the U.S. mission, who had himself learned about it from a radio broadcast.[76]

Extensive logistical installations and large amounts of supplies were found and destroyed, but as reporting from the American command in Saigon disclosed, still larger amounts of military material had already been moved further from the border to shelter it from the incursion into Cambodia by the U.S. and South Vietnam.[77]

One month prior, the North Vietnamese had launched an offensive (Campaign X) of its own against FANK forces at the request of the Khmer Rouge[78] and in order to protect and expand their Base Areas and logistical system.[79] By June, three months after the removal of Sihanouk, they had swept government forces from the entire northeastern third of the country. After defeating those forces, the North Vietnamese turned the newly won territories over to the local insurgents. The Khmer Rouge also established "liberated" areas in the south and the southwestern parts of the country, where they operated independently of the North Vietnamese.[29]

Opposing sides

As combat operations quickly revealed, the two sides were badly mismatched. FANK, whose ranks had been increased by thousands of young urban Cambodians who had flocked to join it in the months following the removal of Sihanouk, had expanded well beyond its capacity to absorb the new men.[80] Later, given the press of tactical operations and the need to replace combat casualties, there was insufficient time to impart needed skills to individuals or to units, and lack of training remained the bane of FANK's existence until its collapse.[81] During the period 1974–1975, FANK forces officially grew from 100,000 to approximately 250,000 men, but probably only numbered around 180,000 due to payroll padding by their officers and due to desertions.[82]

U.S. military aid (ammunition, supplies, and equipment) was funneled to FANK through the Military Equipment Delivery Team, Cambodia (MEDTC). Authorized a total of 113 officers and men, the team arrived in Phnom Penh in 1971,[83] under the overall command of CINCPAC Admiral John S. McCain Jr.[84] The attitude of the Nixon administration could be summed up by the advice given by Henry Kissinger to the first head of the liaison team, Colonel Jonathan Ladd: "Don't think of victory; just keep it alive."[85] Nevertheless, McCain constantly petitioned the Pentagon for more arms, equipment, and staff for what he proprietarily viewed as "my war".[86]

There were other problems. The officer corps of FANK was generally corrupt and greedy.[87] The inclusion of "ghost" soldiers allowed massive payroll padding; ration allowances were kept by the officers while their men starved; and the sale of arms and ammunition on the black market (or to the enemy) was commonplace.[88][89] Worse, the tactical ineptitude among FANK officers was as common as their greed.[90] Lon Nol frequently bypassed the general staff and directed operations down to battalion-level while also forbidding any real coordination between the army, navy and air force.[91]

The common soldiers fought bravely at first, but they were saddled with low pay (with which they had to purchase their own food and medical care), ammunition shortages, and mixed equipment. Due to the pay system, there were no allotments for their families, who were, therefore, forced to follow their husbands/sons into the battle zones. These problems (exacerbated by continuously declining morale) only increased over time.[87]

At the beginning of 1974, the Cambodian army inventory included 241,630 rifles, 7,079 machine guns, 2,726 mortars, 20,481 grenade launchers, 304 recoilless rifles, 289 howitzers, 202 APCs, and 4,316 trucks. The Khmer Navy had 171 vessels; the Khmer Air Force had 211 aircraft, including 64 North American T-28s, 14 Douglas AC-47 gunships and 44 helicopters. American Embassy military personnel – who were only supposed to coordinate the arms aid program – sometimes found themselves involved in prohibited advisory and combat tasks.

When PAVN forces were supplanted, it was by the tough, rigidly indoctrinated peasant army of the Khmer Rouge with its core of seasoned leaders, who now received the full support of Hanoi. Khmer Rouge forces, which had been reorganized at an Indochinese summit held in Guangzhou, China in April 1970, would grow from 12 to 15,000 in 1970 to 35–40,000 by 1972, when the so-called "Khmerization" of the conflict took place and combat operations against the Republic were handed over completely to the insurgents.[92]

The development of these forces took place in three stages. 1970 to 1972 was a period of organization and recruitment, during which Khmer Rouge units served as auxiliaries to the PAVN. From 1972 to mid-1974, the insurgents formed units of battalion and regimental size. It was during this period that the Khmer Rouge began to break away from Sihanouk and his supporters and the collectivization of agriculture was begun in the "liberated" areas. Division-sized units were being fielded by 1974–1975, when the party was on its own and began the radical transformation of the country.[93]

With the fall of Sihanouk, Hanoi became alarmed at the prospect of a pro-Western regime that might allow the Americans to establish a military presence on their western flank. To prevent that from happening, they began transferring their military installations away from the border regions to locations deeper within Cambodian territory. A new command center was established at the city of Kratié and the timing of the move was propitious. President Nixon was of the opinion that:

We need a bold move in Cambodia to show that we stand with Lon Nol...something symbolic...for the only Cambodian regime that had the guts to take a pro-Western and pro-American stand.[76]

Chenla II

During the night of 21 January 1971, a force of 100 PAVN/Viet Cong commandos attacked Pochentong airfield, the main base of the Khmer Air Force. In this one action, the raiders destroyed almost the entire inventory of government aircraft, including all of its fighter planes. This may have been a blessing in disguise, however, since the air force was largely composed of old (even obsolete) Soviet aircraft. The Americans soon replaced the airplanes with more advanced models. The attack did, however, stall a proposed FANK offensive. Two weeks later, Lon Nol had a stroke and was evacuated to Hawaii for treatment. It had been a mild stroke, however, and the general recovered quickly, returning to Cambodia after only two months.[citation needed]

It was not until 20 August that FANK launched Operation Chenla II, its first offensive of the year. The objective of the campaign was to clear Route 6 of enemy forces and thereby reopen communications with Kompong Thom, the Republic's second largest city, which had been isolated from the capital for more than a year. The operation was initially successful, and the city was relieved. The PAVN and Khmer Rouge counterattacked in November and December, annihilating government forces in the process. There was never an accurate count of the losses, but the estimate was "on the order of ten battalions of personnel and equipment lost plus the equipment of an additional ten battalions."[94] The strategic result of the failure of Chenla II was that the offensive initiative passed completely into the hands of PAVN and the Khmer Rouge.[citation needed]

Agony of the Khmer Republic (1972–1975)

Struggling to survive

From 1972 through 1974, the war was conducted along FANK's lines of communications north and south of the capital. Limited offensives were launched to maintain contact with the rice-growing regions of the northwest and along the Mekong River and Route 5, the Republic's overland connections to South Vietnam. The strategy of the Khmer Rouge was to gradually cut those lines of communication and squeeze Phnom Penh. As a result, FANK forces became fragmented, isolated, and unable to lend one another mutual support.[citation needed]

The main U.S. contribution to the FANK effort came in the form of the bombers and tactical aircraft of the U.S. Air Force. When President Nixon launched the incursion in 1970, American and South Vietnamese troops operated under an umbrella of air cover that was designated Operation Freedom Deal. When those troops were withdrawn, the air operation continued, ostensibly to interdict PAVN/Viet Cong troop movements and logistics.[95] In reality (and unknown to the U.S. Congress and American public), they were utilized to provide tactical air support to FANK.[96] As a former U.S. military officer in Phnom Penh reported, "the areas around the Mekong River were so full of bomb craters from B-52 strikes that, by 1973, they looked like the valleys of the moon."[97]

On 10 March 1972, just before the newly renamed Constituent Assembly was to approve a revised constitution, Lon Nol suspended the deliberations. He then forced Cheng Heng, the head of state since Sihanouk's deposition, to surrender his authority to him. On the second anniversary of the coup, Lon Nol relinquished his authority as head of state, but retained his position as prime minister and defense minister.[citation needed]

On 4 June, Lon Nol was elected as the first president of the Khmer Republic in a blatantly rigged election.[98] As per the new constitution (ratified on 30 April), political parties formed in the new nation, quickly becoming a source of political factionalism. General Sutsakhan stated: "the seeds of democratization, which had been thrown into the wind with such goodwill by the Khmer leaders, returned for the Khmer Republic nothing but a poor harvest."[91]

In January 1973, hope was renewed when the Paris Peace Accords were signed, ending the conflict (for the time being) in South Vietnam and Laos. On 29 January, Lon Nol proclaimed a unilateral cease-fire throughout the nation. All U.S. bombing operations were halted in hopes of securing a chance for peace. It was not to be. The Khmer Rouge simply ignored the proclamation and carried on fighting. By March, heavy casualties, desertions, and low recruitment had forced Lon Nol to introduce conscription, and in April insurgent forces launched an offensive that pushed into the suburbs of the capital. The U.S. Air Force responded by launching an intense bombing operation that forced the communists back into the countryside after being decimated by the air strikes.[99] The U.S. Seventh Air Force argued that the bombing prevented the fall of Phnom Penh in 1973 by killing 16,000 of 25,500 Khmer Rouge fighters besieging the city.[100]

By the last day of Operation Freedom Deal (15 August 1973), 250,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on the Khmer Republic, 82,000 tons of which had been released in the last 45 days of the operation.[101] Since the inception of Operation Menu in 1969, the U.S. Air Force had dropped 539,129 tons of ordnance on Cambodia/Khmer Republic.[102]

Shape of things to come

As late as 1972–1973, it was a commonly held belief, both within and outside Cambodia, that the war was essentially a foreign conflict that had not fundamentally altered the nature of the Khmer people.[103] By late 1973, there was a growing awareness among the government and population of Cambodia that the extremism, total lack of concern over casualties, and complete rejection of any offer of peace talks "began to suggest that Khmer Rouge fanaticism and capacity for violence were deeper than anyone had suspected."[103]

Reports of the brutal policies of the organization soon made their way to Phnom Penh and into the population foretelling the violence that was about to consume the nation. There were tales of the forced relocations of entire villages, of the summary execution of any who disobeyed or even asked questions, the forbidding of religious practices, of monks who were defrocked or murdered, and where traditional sexual and marital habits were foresworn.[104][105] War was one thing; the offhand manner in which the Khmer Rouge dealt out death, so contrary to the Khmer character, was quite another.[106] Reports of these atrocities began to surface during the same period in which North Vietnamese troops were withdrawing from the Cambodian battlefields. This was no coincidence. The concentration of the PAVN effort on South Vietnam allowed the Khmer Rouge to apply their doctrine and policies without restraint for the first time.[107]

The Khmer Rouge leadership was almost completely unknown by the public. They were referred to by their fellow countrymen as peap prey – the forest army. Previously, the very existence of the communist party as a component of GRUNK had been hidden.[104] Within the "liberated zones" it was simply referred to as "Angka" – the organization. During 1973, the communist party fell under the control of its most fanatical members, Pol Pot and Son Sen, who believed that "Cambodia was to go through a total social revolution and that everything that had preceded it was anathema and must be destroyed."[107]

Also hidden from scrutiny was the growing antagonism between the Khmer Rouge and their North Vietnamese allies.[107][108] The radical leadership of the party could never escape the suspicion that Hanoi had designs on building an Indochinese federation with the North Vietnamese as its master.[109] The Khmer Rouge were ideologically tied to the Chinese, while North Vietnam's chief supporters, the Soviet Union, still recognized the Lon Nol government as legitimate.[110]

After the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, PAVN cut off the supply of arms to the Khmer Rouge, hoping to force them into a cease-fire.[107][111] When the Americans were freed by the signing of the accords to turn their air power completely on the Khmer Rouge, this too was blamed on Hanoi.[112] During the year, these suspicions and attitudes led the party leadership to carry out purges within their ranks. Most of the Hanoi-trained members were then executed on the orders of Pol Pot.[113]

As time passed, the need of the Khmer Rouge for the support of Prince Sihanouk lessened. The organization demonstrated to the people of the 'liberated' areas in no uncertain terms that open expressions of support for Sihanouk would result in their liquidation.[114] Although the prince still enjoyed the protection of the Chinese, when he made public appearances overseas to publicize the GRUNK cause, he was treated with almost open contempt by Ministers Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan.[115] In June, the prince told Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci that when "they [the Khmer Rouge] have sucked me dry, they will spit me out like a cherry stone."[116]

By the end of 1973, Sihanouk loyalists had been purged from all of GRUNK's ministries, and all of the prince's supporters within the insurgent ranks were also eliminated.[107] Shortly after Christmas, as the insurgents were gearing up for their final offensive, Sihanouk spoke with the French diplomat Etienne Manac'h. He said that his hopes for a moderate socialism akin to Yugoslavia's must now be totally dismissed. Hoxha's Albania, he said, would be the model.[117]

Fall of Phnom Penh

By the time the Khmer Rouge initiated their dry-season offensive to capture the beleaguered Cambodian capital on 1 January 1975, the Republic was in chaos. The economy had been gutted, the transportation network had been reduced to air and waterways, the rice harvest had fallen by one-quarter, and the supply of freshwater fish (the chief source of protein for the country) had declined drastically. The cost of food was 20 times greater than pre-war levels, while unemployment was not even measured anymore.[118]

Phnom Penh, which had a pre-war population of around 600,000, was overwhelmed by refugees (who continued to flood in from the steadily collapsing defense perimeter), growing to a size of around two million. These helpless and desperate civilians had no jobs and little in the way of food, shelter, or medical care. Their condition (and the government's) only worsened when Khmer Rouge forces gradually gained control of the banks of the Mekong. From the riverbanks, their mines and gunfire steadily reduced the river convoys through which 90 percent of the Republic's supplies moved, bringing relief supplies of food, fuel, and ammunition to the slowly starving city from South Vietnam.[119]

After the river was effectively blocked in early February, the U.S. began an airlift of supplies into Pochentong Airport. This became increasingly risky, however, due to communist rocket and artillery fire, which constantly rained down on the airfield and city. The Khmer Rouge cut off overland supplies to the city for more than a year before it fell on 17 April 1975. Reports from journalists stated that the Khmer Rouge shelling "tortured the capital almost continuously," inflicting "random death and mutilation" on millions of trapped civilians.[119]

Desperate but determined units of FANK soldiers, many of whom had run out of ammunition, dug in around the capital and fought until they were overrun as the Khmer Rouge advanced. By the last week of March 1975, approximately 40,000 communist troops had surrounded the capital and began preparing to deliver the coup de grace to about half as many FANK forces.[120]

Lon Nol resigned and left the country on 1 April, hoping that a negotiated settlement might still be possible if he was absent from the political scene.[121] Saukam Khoy became acting president of a government that had less than three weeks to live. Last-minute efforts on the part of the U.S. to arrange a peace agreement involving Sihanouk ended in failure. When a vote in the U.S. Congress for a resumption of American air support failed, panic and a sense of doom pervaded the capital. The situation was best described by General Sak Sutsakhan (now FANK chief of staff):

The picture of the Khmer Republic which came to mind at that time was one of a sick man who survived only by outside means and that, in its condition, the administration of medication, however efficient it might be, was probably of no further value.[122]

On 12 April, concluding that all was lost, the U.S. evacuated its embassy personnel by helicopter during Operation Eagle Pull. The 276 evacuees included U.S. Ambassador John Gunther Dean, other American diplomatic personnel, Acting President Saukam Khoy, senior Khmer Republic government officials and their families, and members of the news media. In all, 82 U.S., 159 Cambodian, and 35 third-country nationals were evacuated.[123] Although invited by Ambassador Dean to join the evacuation (and much to the Americans' surprise), Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak, Long Boret, Lon Non (Lon Nol's brother), and most members of Lon Nol's cabinet declined the offer.[124] All of them chose to share the fate of their people. Their names were not published on the death lists and many trusted the Khmer Rouge's assertions that former government officials would not be murdered, but would be welcome in helping to rebuild a new Cambodia.[citation needed]

After the Americans (and Saukam Khoy) had departed, a seven-member Supreme Committee, headed by General Sak Sutsakhan, assumed authority over the collapsing Republic. By 15 April, the last solid defenses of the city were overcome by the communists. In the early morning hours of 17 April, the committee decided to move the seat of government to Oddar Meanchey Province in the northwest. Around 10:00, the voice of General Mey Si Chan of the FANK general staff broadcast on the radio, ordering all FANK forces to cease firing, since "negotiations were in progress" for the surrender of Phnom Penh.[125]

The war was over, and the Khmer Rouge announced the establishment of the Democratic Kampuchea. Long Boret was captured and beheaded on the grounds of the Cercle Sportif, while a similar fate would await Sirik Matak and other senior officials.[126] Captured FANK officers were taken to the Monoram Hotel to write their biographies and then taken to the Olympic Stadium, where they were executed.[126]: 192–3 Khmer Rouge troops immediately began to forcibly empty the capital city, driving the population into the countryside and killing tens of thousands of civilians in the process. The Year Zero had begun.

Causes of death

Of 240,000 Khmer–Cambodian deaths during the war, French demographer Marek Sliwinski attributes 46.3% to firearms, 31.7% to assassinations (a tactic primarily used by the Khmer Rouge), 17.1% to (mainly U.S.) bombing, and 4.9% to accidents. An additional 70,000 Cambodians of Vietnamese descent were massacred with the complicity of Lon Nol's government during the war.[5]

War crimes

Atrocities

In the Cambodian Civil War, Khmer Rouge insurgents reportedly committed atrocities during the war. These include the murder of civilians and POWs by slowly sawing off their heads part by part each day,[127] the destruction of Buddhist wats and the killing of monks,[128] attacks on refugee camps involving the deliberate murder of babies and bomb threats against foreign aid workers,[129] the abduction and assassination of journalists,[130] and the shelling of Phnom Penh for more than a year.[131] Journalist accounts stated that the Khmer Rouge shelling "tortured the capital almost continuously", inflicting "random death and mutilation" on 2 million trapped civilians.[132]

The Khmer Rouge forcibly evacuated the entire city after taking it, in what has been described as a death march: François Ponchaud wrote: "I shall never forget one cripple who had neither hands nor feet, writhing along the ground like a severed worm, or a weeping father carrying his ten-year-old daughter wrapped in a sheet tied around his neck like a sling, or the man with his foot dangling at the end of a leg to which it was attached by nothing but skin";[133] John Swain recalled that the Khmer Rouge were "tipping out patients from the hospitals like garbage into the streets ... In five years of war, this is the greatest caravan of human misery I have seen."[134]

Use of children

The Khmer Rouge exploited thousands of desensitized, conscripted children in their early teens to commit mass murder and other atrocities during the genocide.[9] The indoctrinated children were taught to follow any order without hesitation.[9] During its guerrilla war after it was deposed, the Khmer Rouge continued to use children widely until at least 1998.[135] During this period, the children were deployed mainly in unpaid support roles, such as ammunition-carriers, and also as combatants.[135]

See also

- Cambodia Tribunal

- Cambodian humanitarian crisis

- Economic history of Cambodia

- History of Cambodia

- Weapons of the Cambodian Civil War

- Cagetory:Battles of the August Revolution

Notes

- ^ Beginning in 1966, Cambodians sold 100,000 tons of Cambodian rice to PAVN, who offered the world price and paid in U.S. dollars. The government paid only a low fixed price and thereby lost the taxes and profits that would have been gained. The drop in rice for export (from 583,700 tons in 1965 to 199,049 tons in 1966) elevated an economic crises that grew worse with each passing year.[15]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f Spencer C. Tucker (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-85109-960-3. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Sarah Streed (2002). Leaving the house of ghosts: Cambodian refugees in the American Midwest. McFarland. p. 10. ISBN 0-7864-1354-9. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality Crises: The Case of Cambodia, 1970–1979". Forced Migration and Mortality. National Academies Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9780309073349.

Subsequent reevaluations of the demographic data situated the death toll for the [civil war] in the order of 300,000 or less.

cf. "Cambodia: U.S. bombing, civil war, & Khmer Rouge". World Peace Foundation. 7 August 2015.On the higher end of estimates, journalist Elizabeth Becker writes that 'officially, more than half a million Cambodians died on the Lon Nol side of the war; another 600,000 were said to have died in the Khmer Rouge zones.' However, it is not clear how these numbers were calculated or whether they disaggregate civilian and soldier deaths. Others' attempts to verify the numbers suggest a lower number. Demographer Patrick Heuveline has produced evidence suggesting a range of 150,000 to 300,000 violent deaths from 1970 to 1975. In an article reviewing different sources about civilian deaths during the civil war, Bruce Sharp argues that the total number is likely to be around 250,000 violent deaths. ... [Heuveline]'s conclusion is that an average of 2.52 million people (range of 1.17–3.42 million) died as a result of regime actions between 1970 and 1979, with an average estimate of 1.4 million (range of 1.09–2.16 million) directly violent deaths.

- ^ Banister, Judith; Johnson, E. Paige (1993). "After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia". Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community. Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. p. 87. ISBN 9780938692492.

An estimated 275,000 excess deaths. We have modeled the highest mortality that we can justify for the early 1970s.

- ^ a b Sliwinski, Marek (1995). Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique. Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 42–43, 48. ISBN 978-2-738-43525-5.

- ^ a b c d Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 90.

- ^ a b "Cambodia: U.S. Invasion, 1970s". Global Security. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Dmitry Mosyakov, "The Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese Communists: A History of Their Relations as Told in the Soviet Archives," in Susan E. Cook, ed., Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda (Yale Genocide Studies Program Monograph Series No. 1, 2004), p54ff. Available online at: www.yale.edu/gsp/publications/Mosyakov.doc "In April–May 1970, many North Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in response to the call for help addressed to Vietnam not by Pol Pot, but by his deputy Nuon Chea. Nguyen Co Thach recalls: "Nuon Chea has asked for help and we have liberated five provinces of Cambodia in ten days.""

- ^ a b c Southerland, D (20 July 2006). "Cambodia Diary 6: Child Soldiers – Driven by Fear and Hate". Archived from the original on 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b Shawcross, William, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979, p. 222

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown et al., pp. 54–58.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 83.

- ^ a b Lipsman and Doyle, p. 127.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. 465, fn. 24.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 85.

- ^ Chandler, pp. 153–156.

- ^ Osborne, p. 187.

- ^ Chandler, p. 157.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 86.

- ^ Chandler, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Osborne, p. 192.

- ^ a b Lipsman and Doyle, p. 130.

- ^ Chandler, p. 165.

- ^ a b Chandler, p. 166.

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 87.

- ^ Chandler, p. 128.

- ^ Deac, p. 55.

- ^ Chandler, p. 141.

- ^ a b Sutsakhan, p. 32.

- ^ Chandler, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 89.

- ^ Lipsman and Doyle, p. 140.

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 88.

- ^ Karnow, p. 590.

- ^ Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Command History 1967, Annex F, Saigon, 1968, p. 4.

- ^ Nalty, pp. 127–133.

- ^ Clymer, Kenton (2004), United States and Cambodia: 1969–2000, Routledge, pg. 12.

- ^ Shawcross, pps. 68–71 & 93–94.

- ^ Clymer, Kenton (2013). The United States and Cambodia, 1969–2000: A Troubled Relationship. Routledge. pp. 14–16. ISBN 9781134341566.

- ^ Clymer, Kenton (2013). The United States and Cambodia, 1969–2000: A Troubled Relationship. Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781134341566.

- ^ Alex J. Bellamy (2012). Massacres and Morality: Mass Atrocities in an Age of Civilian Immunity. Oxford University Press. p. 200.

- ^ a b Owen, Taylor; Kiernan, Ben (October 2006). "Bombs Over Cambodia" (PDF). The Walrus: 62–69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2014. Kiernan and Owen later revised their estimate of 2.7 million tons of U.S. bombs dropped on Cambodia down to the previously accepted figure of roughly 500,000 tons: See Kiernan, Ben; Owen, Taylor (26 April 2015). "Making More Enemies than We Kill? Calculating U.S. Bomb Tonnages Dropped on Laos and Cambodia, and Weighing Their Implications". The Asia-Pacific Journal. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016.

- ^ Valentino, Benjamin (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780801472732.

- ^ The Crime of Cambodia: Shawcross on Kissinger's Memoirs New York Magazine, 5 November 1979

- ^ The Economist, 26 February 1983.

- ^ Washington Post, 23 April 1985.

- ^ a b Rodman, Peter, Returning to Cambodia Archived 18 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Brookings Institution, 23 August 2007.

- ^ Lind, Michael, Vietnam: The Necessary War: A Reinterpretation of America's Most Disastrous Military Conflict, Free Press, 1999.

- ^ Chandler, David 2000, Brother Number One: A Political Biography of Pol Pot, Revised Edition, Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, pp. 96–7. "The bombing had the effect the Americans wanted—it broke the communist encirclement of Phnom Penh. The war was to drag on for two more years."

- ^ Timothy Carney, "The Unexpected Victory," in Karl D. Jackson, ed., Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous With Death (Princeton University Press, 1989), pp. 13–35.

- ^ Pribbenow, p. 257.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 118.

- ^ Deac, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Lipsman and Doyle, p. 142.

- ^ Sutsakhan, p. 42.

- ^ Lipsman and Doyle, p. 143.

- ^ Chandler, David P. (2000). A history of Cambodia (3rd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 204. ISBN 0813335116. OCLC 42968022.

- ^ Shawcross, pp. 112–122.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f Lipsman and Doyle, p. 144.

- ^ Deac, p. 69.

- ^ Deac, p. 71.

- ^ Deac, p. 75.

- ^ Lipsman and Doyle, p. 145.

- ^ Lipsman and Doyle, p. 146.

- ^ a b David P. Chandler, The Tragedy of Cambodian History, New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1991, p. 231.

- ^ Chandler, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Chandler, p. 200.

- ^ Osborne, pp. 214, 218.

- ^ Chandler, p. 201.

- ^ Chandler, p. 202.

- ^ a b Szalontai, Balázs (2014). "Political and Economic Relations between Communist States". In Smith, Stephen Anthony (ed.). Oxford Handbook in the History of Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 316.

- ^ Lipsman and Brown, p. 146.

- ^ "Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975." University Press of Kansas, May 2002 (original 1995). Translation by Merle L. Pribbenow. Pages 256–257.

- ^ Karnow, p. 607.

- ^ a b Karnow, p. 608.

- ^ Deac, p. 79.

- ^ Dmitry Mosyakov, "The Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese Communists: A History of Their Relations as Told in the Soviet Archives," in Susan E. Cook, ed., Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda (Yale Genocide Studies Program Monograph Series No. 1, 2004), p54ff

- ^ Deac, p. 72. PAVN units involved included the 1st, 5th, 7th, and 9th Divisions and the PAVN/NLF C40 Division. Artillery support was provided by the 69th Artillery Division.

- ^ Sutsakhan, p. 48.

- ^ Deac, p. 172.

- ^ Sutsakhan, p. 39.

- ^ Nalty, p. 276.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 190.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 169.

- ^ Shawcross, pp. 169, 191.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 108.

- ^ Shawcross, pp. 313–315.

- ^ Chandler, p. 205.

- ^ General Creighton Abrams, commander of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam dispatched General Conroy to Phnom Penh to observe the situation and report back. Conroy's conclusions were that the Cambodian officer corps "had no combat experience...did not know how to run an army nor were they seemingly concerned about their ignorance in the face of the mortal threats that they faced." Shaw, p. 137.

- ^ a b Sutsakhan, p. 89.

- ^ Sutsakhan, pp. 26–27.

- ^ The evolution of the communist forces is described in Sutsakhan, pp. 78–82.

- ^ Sutsakhan, p. 79

- ^ Nalty, p. 199.

- ^ Douglas Pike, John Prados, James W. Gibson, Shelby Stanton, Col. Rod Paschall, John Morrocco, and Benjamin F. Schemmer, War in the Shadows. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1988, p. 146.

- ^ War in the Shadows, p. 149.

- ^ Chandler, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 100.

- ^ Etcheson, Craig (1984). The Rise and Demise of Democratic Kampuchea. Westview. p. 118. ISBN 0-86531-650-3.

- ^ Morrocco, p. 172.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 297.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 106.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 322.

- ^ Osborne, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 107.

- ^ Chandler, p. 216.

- ^ Ideology was not all that separated the two communist groups. Many Cambodian communists shared racially based views about the Vietnamese with their fellow countrymen. Deac, pp. 216, 230.

- ^ Deac, p. 68.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 281.

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 107

- ^ Chandler, p. 211.

- ^ Chandler, p. 231.

- ^ Osborne, p. 224.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 321.

- ^ Shawcross, p. 343.

- ^ Lipsman and Weiss, p. 119.

- ^ a b Barron, John and Anthony Paul (1977), Murder of a Gentle Land, Reader's Digest Press, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Snepp, p. 279.

- ^ Deac, p. 218.

- ^ Sutsakhan, p. 155.

- ^ The Republic's five-year war cost the U.S. about a million dollars a day – a total of $1.8 billion in military and economic aid. Operation Freedom Deal added another $7 billion. Deac, p. 221.

- ^ Isaacs, Hardy and Brown, p. 111.

- ^ Ponchaud, p. 7.

- ^ a b Becker, Elizabeth (1998). When the war was over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution. Public Affairs. p. 160. ISBN 9781891620003.

- ^ Kirk, Donald (14 July 1974). "I watched them saw him 3 days". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Kirk, Donald (14 July 1974). "Khmer Rouge's Bloody War on Trapped Villagers". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Yates, Ronald (17 March 1975). "Priest Won't Leave Refugees Despite Khmer Rouge Threat". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Power, Samantha (2002). A Problem From Hell. Perennial Books. pp. 98–99.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (28 January 1974). "The Agony of Phnom Penh". The Washington Post.

- ^ Barron, John; Paul, Anthony (1977). Murder of a Gentle Land. Reader's Digest Press. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Ponchaud, François (1978). Cambodia Year Zero. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Swain, John (1999). River of Time: A Memoir of Vietnam and Cambodia. Berkley Trade.

- ^ a b "Global Report on Child Soldiers". child-soldiers.org. Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers. 2001. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

Sources

Government documents

- Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002). Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. trans. Pribbenow, Merle. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- Nalty, Bernard C. (2000). Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968–1975. Washington DC: Air Force History and Museums Program.

- Sutsakhan, Lt. Gen. Sak, The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. Washington DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 1987.

Biographies

- Osborne, Milton (1994). Sihanouk: Prince of Light, Prince of Darkness. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-642-5.

Secondary sources

- Chandler, David P. (1991). The Tragedy of Cambodian History. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04919-6.

- Deac, Wilfred P. (2000). Road to the Killing Fields: the Cambodian War of 1970–1975. College Station TX: Texas A&M University Press.

- Dougan, Clark; Fulghum, David; et al. (1985). The Fall of the South. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-16-6.

- Isaacs, Arnold; Hardy, Gordon (1988). Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-24-7.

- Karnow, Stanley (1983). Vietnam: A History. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-74604-5.

- Kinnard, Douglas, The War Managers. Wayne NJ: Avery Publishing Group, 1988.

- Kroth, Jerry (2012). Duped!: Delusion, denial, and the end of the American Dream. Jerry Kroth. ISBN 978-0-936618-08-1.

- Lipsman, Samuel; Doyle, Edward; et al. (1983). Fighting for Time: 1969–1970. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-07-7.

- Lipsman, Samuel; Weiss, Stephen (1985). The False Peace: 1972–74. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-15-8.

- Morris, Stephen (1999). Why Vietnam invaded Cambodia : political culture and the causes of war. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3049-0.

- Morrocco, John (1985). Rain of Fire: Air War, 1969–1973. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-14-X.

- Osborne, Milton (1979). Before Kampuchea: Preludes to Tragedy. Sydney: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-86861-249-9.

- Pike Douglas, John Prados, James W. Gibson, Shelby Stanton, Col. Rod Paschall, John Morrocco, and Benjamin F. Schemmer, War in the Shadows. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1991.

- Ponchaud, Francois, Cambodia: Year Zero. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1981.

- Shaw, John M. (2005). The Cambodian Campaign: the 1970 offensive and America's Vietnam War. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 0-7006-1405-2.

- Shawcross, William (1979). Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. University of Michigan. ISBN 0-671-23070-0.

- Snepp, Frank (1977). Decent Interval: An Insider's Account of Saigon's Indecent End Told by the CIA's Chief Strategy Analyst in Vietnam. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-40743-1.

- Tully, John (2005). A short history of Cambodia: from empire to survival. Singapore: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-763-8.

External links

- Cambodian Civil War

- 1960s in Cambodia

- 1970s in Cambodia

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Civil wars of the 20th century

- Communist revolutions

- Military history of Cambodia

- Revolution-based civil wars

- Wars involving Cambodia

- Wars involving Vietnam

- Vietnam War

- 1967 establishments in Cambodia

- 1975 disestablishments in Cambodia

- 20th century in Cambodia

- Insurgencies in Asia