Casselton, North Dakota

Casselton, North Dakota | |

|---|---|

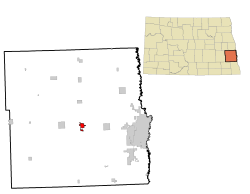

Location of Casselton, North Dakota | |

| Coordinates: 46°53′50″N 97°12′46″W / 46.89722°N 97.21278°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Dakota |

| County | Cass |

| Founded | August 8, 1876 |

| Incorporated | 1880 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Michael Faught |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.192 sq mi (5.677 km2) |

| • Land | 2.162 sq mi (5.601 km2) |

| • Water | 0.030 sq mi (0.077 km2) |

| Elevation | 932 ft (284 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 2,479 |

• Estimate (2023)[4] | 2,472 |

| • Density | 1,143.0/sq mi (441.4/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC–6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | 58012 |

| Area code | 701 |

| FIPS code | 38-12700 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1035957[2] |

| Sales tax | 7.5%[5] |

| Website | casselton.com |

Casselton is a city in Cass County, North Dakota, United States. The population was 2,479 at the 2020 census.[3] making it the 20th largest city in North Dakota. Casselton was founded in 1876. The city is named in honor of George Washington Cass, a president of the Northern Pacific Railway, which established a station there in 1876 to develop a town for homesteaders. Casselton is the hometown of five North Dakota governors.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

Casselton had its origin in 1873 when the Northern Pacific Railway sent Mike Smith to plant cottonwood and willow trees in the area to serve as windbreaks along the right-of-way. They planned to harvest the trees for lumber to use as railroad ties, but the experiment failed for a number of reasons.

In 1874, Emil Priewe and his wife joined Mike Smith at the station. The Priewe's son, Harry, was born on March 28, 1875, in a sod shanty, the first child born in the developing village. Others came to settle and by 1880, the town had a population of 376, according to the official census. A school was organized in 1876 and the town was incorporated as a village in 1880.

The hamlet was variously called "the Nursery", "Goose Creek" and "Swan Creek", named for the stream that meandered through the area. In 1876, the railroad established a station called Casstown, after George Cass, the railroad president. When the post office was established on August 8, 1876, the name Casselton was designated.

During the 1870s, George Cass and Peter Cheney traded their railroad stock for 10,000 acres (40 km2) of land near Casselton and decided to develop the property as one large farm, rather than dividing the land into small tracts. They employed Oliver Dalrymple, of southern Minnesota, to head the operation. These Bonanza farms became highly successful and proved that the prairie was very suitable for agriculture.

Various means were used to attract immigrants from Europe and migrants from the East looking for a piece of land or the chance to become tradesmen and professionals. Casselton's population reached 1,365 in 1885.

The Great Northern Railway had an additional influence in the growth of Casselton. Several branches radiated from the city. The railroad excavated a reservoir to supply water for its steam engines. In 1906 the railway constructed a round house and service center which operated until 1920. In the 1920s, railroad personnel were transferred to other locations, and as a result, the population of Casselton fell 285 persons between 1920 and 1930.

Casselton installed a city water and sewer system in the mid-1920s. Water was pumped from artesian wells, and stored in a standpipe which was located on the east part of town. Today, that site is used as a winter skating rink. Looking like a gigantic culvert, the standpipe was 110 feet (34 m) tall and was kept until 1956.

By 1957, the Great Northern Railway no longer had a need for the Casselton reservoir. They deeded the 73 acres (300,000 m2) of land, which encompassed that body of water, to the City of Casselton. The reservoir was developed to be used as a municipal water supply until March 1978, when the city's water started to come from the Leonard Phase of the Cass Water Users System. The reservoir area has since been developed into a recreational center with softball diamonds, tennis courts, picnic tables and the like.

The streets of Casselton were improved through municipal and state efforts. In 1927, the downtown roads were graveled. In 1930, as a US Works Progress Administration project under the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration during the Great Depression, the federal government paid local workers to pave State Highway No. 18 through the city. After World War II, the business district streets were paved with concrete. Since that time, all streets and avenues have been hard-topped, and a modern storm sewer system was installed at the same time.

The 1996–1997 school year opened with a newly completed, nearly $8 million Central Cass Public School building. It replaced a three-story building on the same site, that was dedicated in 1912 and cost $50,000. The school district covers nearly 400 square miles (1,000 km2), and attracts over 800 students. Because of the continued growth, an addition to the school complex was completed in time for the 2003–2004 school year.

Casselton is known for its population of American red squirrels. Central Cass High School uses the squirrel as its mascot.[7]

2013 train derailment

On December 30, 2013, a westbound BNSF train carrying soybeans derailed approximately one mile west of Casselton. An adjacent eastbound BNSF train carrying crude oil struck wreckage from the westbound train (accident location 46°54′4.82″N 97°13′59.42″W / 46.9013389°N 97.2331722°W). The collision ignited the crude oil and caused a chain of large explosions, which were heard and felt several miles away.[8][9][10] The resulting fireball created a massive cloud of black smoke, which prompted authorities to issue a voluntary evacuation of the city and surrounding area as a precaution. The National Transportation Safety Board conducted an investigation, and in 2017 issued findings of probable cause, starting with a broken axle on the westbound train.[11][12][13]

Although no casualties were reported, as the crew of the crude oil train abandoned the lead locomotives before they were engulfed in flames as soon as they had derailed and come to stop in a snowbank,[14] the incident occurred in proximity to a populated area and renewed safety concerns regarding the transportation of hazardous materials by rail, especially in the wake of the Lac-Mégantic derailment in Canada earlier in the year. Casselton mayor Ed McConnell, acknowledging that the town "dodged a bullet", publicly called on the federal government to review the dangers and urged lawmakers to consider pipelines as a safer option.[15]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.192 square miles (5.68 km2), of which, 2.162 square miles (5.60 km2) is land and 0.030 square miles (0.08 km2) is water.[1]

Climate

This climatic region is typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and cold (sometimes severely cold) winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Casselton has a humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfb" on climate maps.

| Climate data for Casselton, North Dakota, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1984–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 56 (13) |

54 (12) |

76 (24) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

101 (38) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

98 (37) |

93 (34) |

76 (24) |

58 (14) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 40.4 (4.7) |

42.2 (5.7) |

57.1 (13.9) |

77.5 (25.3) |

88.1 (31.2) |

91.4 (33.0) |

92.1 (33.4) |

91.8 (33.2) |

89.0 (31.7) |

80.5 (26.9) |

59.8 (15.4) |

43.4 (6.3) |

94.8 (34.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 16.9 (−8.4) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

35.0 (1.7) |

52.8 (11.6) |

67.6 (19.8) |

77.0 (25.0) |

80.8 (27.1) |

79.9 (26.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

55.6 (13.1) |

37.8 (3.2) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

51.6 (10.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 7.8 (−13.4) |

11.8 (−11.2) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

41.7 (5.4) |

55.4 (13.0) |

66.0 (18.9) |

69.7 (20.9) |

67.8 (19.9) |

58.9 (14.9) |

44.7 (7.1) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

41.1 (5.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −1.4 (−18.6) |

2.1 (−16.6) |

16.6 (−8.6) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

43.2 (6.2) |

54.9 (12.7) |

58.6 (14.8) |

55.8 (13.2) |

46.4 (8.0) |

33.8 (1.0) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

6.6 (−14.1) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −23.6 (−30.9) |

−19.2 (−28.4) |

−8.0 (−22.2) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

43.4 (6.3) |

47.6 (8.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

0.5 (−17.5) |

−15.5 (−26.4) |

−25.5 (−31.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −37 (−38) |

−39 (−39) |

−23 (−31) |

1 (−17) |

19 (−7) |

35 (2) |

41 (5) |

36 (2) |

22 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

−33 (−36) |

−34 (−37) |

−39 (−39) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.54 (14) |

0.57 (14) |

1.09 (28) |

1.49 (38) |

3.16 (80) |

4.43 (113) |

3.69 (94) |

2.62 (67) |

2.79 (71) |

2.33 (59) |

0.80 (20) |

0.69 (18) |

24.20 (615) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.4 (19) |

6.6 (17) |

6.2 (16) |

3.3 (8.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

4.4 (11) |

8.1 (21) |

36.7 (94.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 4.1 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 10.7 | 11.4 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 84.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.6 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 16.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 360 | — | |

| 1890 | 840 | 133.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,207 | 43.7% | |

| 1910 | 1,553 | 28.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,538 | −1.0% | |

| 1930 | 1,253 | −18.5% | |

| 1940 | 1,358 | 8.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,373 | 1.1% | |

| 1960 | 1,394 | 1.5% | |

| 1970 | 1,485 | 6.5% | |

| 1980 | 1,661 | 11.9% | |

| 1990 | 1,601 | −3.6% | |

| 2000 | 1,855 | 15.9% | |

| 2010 | 2,329 | 25.6% | |

| 2020 | 2,479 | 6.4% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 2,472 | [4] | −0.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] 2020 Census[3] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 2,290 | 92.4% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 20 | 0.8% |

| Native American (NH) | 22 | 0.9% |

| Asian (NH) | 3 | 0.1% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 0 | 0.0% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 8 | 0.3% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 92 | 3.7% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 44 | 1.8% |

| Total | 2,479 | 100.0% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 2,479 people, 941 households, and 661 families residing in the city.[20] There were 1,011 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 92.8% White, 0.8% African American, 0.9% Native American, 0.1% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from some other races and 4.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.8% of the population.[21]

2010 census

As of the 2010 census, there were 2,329 people, 874 households, and 633 families living in the city. The population density was 1,245.5 inhabitants per square mile (480.9/km2). There were 926 housing units at an average density of 495.2 per square mile (191.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.3% White, 0.1% African American, 0.9% Native American, 0.1% Asian, 0.4% from other races, and 1.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.4% of the population.

There were 874 households, of which 42.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.8% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 27.6% were non-families. 23.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.17.

The median age in the city was 34.6 years. 31.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 27.6% were from 25 to 44; 25.3% were from 45 to 64; and 10.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 51.4% male and 48.6% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 1,855 people, 702 households, and 509 families living in the city. The population density was 1,315.5 inhabitants per square mile (507.9/km2). There were 738 housing units at an average density of 523.4 per square mile (202.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 98.22% White, 0.16% African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.16% Asian, 0.11% from other races, and 1.08% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.49% of the population.

There were 702 households, out of which 40.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 63.0% were married couples living together, 6.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.4% were non-families. 24.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.64 and the average family size was 3.16.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 31.6% under the age of 18, 5.9% from 18 to 24, 30.5% from 25 to 44, 20.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 106.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $43,259, and the median income for a family was $49,567. Males had a median income of $32,063 versus $22,614 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,248. About 2.6% of families and 5.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.4% of those under age 18 and 12.1% of those age 65 or over.

Area attractions

Casselton was home to the world's largest oil can pile/free standing structure. This tourist attraction was created in 1933 by Max Taubert when a Sinclair gas station occupied the lot that included a hamburger stand. It is approximately 45 feet (14 m) tall, and is made of thousands of oil cans. It was rescued from possible demolition in 2008 by a group of local volunteers.[22]

Transportation

Notable people

- Andrew H. Burke, 2nd governor of North Dakota (1891–1893)

- Jack Dalrymple, 32nd governor of North Dakota, (2010–2016)

- Dwayne A. King, businessman and Minnesota state legislator

- John H. Lang, highly decorated member of both the Canadian army and United States navy.

- William Langer, 17th and 21st governor of North Dakota (1933–1934; 1937–1939), senator (1941–1959)

- George A. Sinner, 29th governor of North Dakota (1985–1992)

- Herman Stern, clothier, businessman, humanitarian, social and economic activist

- Mark Weber, member of the North Dakota Senate

See also

References

- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Casselton, North Dakota

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020–2023". United States Census Bureau. June 23, 2024. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ "Casselton (ND) sales tax rate". Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Nolan, Edward W. (1983). Northern Pacific views: The railroad photography of F. Jay Haynes, 1876–1905. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-917298-11-X.

- ^ "Central Cass Football". maxpreps.com. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ "Casselton train crash a 'huge accident' but a coincidence; Inforum; December 31, 2013". Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Editorial, Reuters (December 30, 2013). "UPDATE 3-Train collision in North Dakota sets oil rail cars ablaze". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "As oil train burns, 2,300 residents of Casselton, N.D., told to flee". Star Tribune. December 30, 2013.

- ^ "NTSB Issues Probable Cause for Casselton, North Dakota, Crude Oil Train Accident".

- ^ "DCA14MR004". www.ntsb.gov. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ NTSB video on YouTube

- ^ "BNSF Railway Train Derailment and Subsequent Train Collision". YouTube.

- ^ "Train derailment: Mayor says ND town dodged bullet". KABC-TV Los Angeles. December 31, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Casselton Agronomy Farm, ND". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Grand Forks". National Weather Service. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Mapleton city, North Dakota".

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ "How many people live in Casselton city, North Dakota". USA Today. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ "Casselton Can Pile that is now World Famous". www.casseltoncanpile.com. Retrieved August 21, 2018.