Child's Play 3

| Child's Play 3 | |

|---|---|

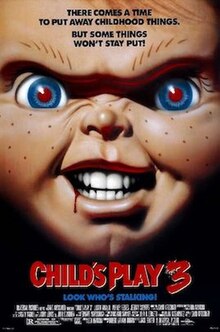

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Bender |

| Written by | Don Mancini |

| Based on | Characters by Don Mancini |

| Produced by | Robert Latham Brown |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John R. Leonetti |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $13 million |

| Box office | $20.5 million[2] |

Child's Play 3 is a 1991 American slasher film and the third installment in the Child's Play film series. The film is written by Don Mancini and directed by Jack Bender. Brad Dourif once again reprised his role as Chucky from the previous films while new cast members include Justin Whalin, Perrey Reeves and Jeremy Sylvers. It was executive-produced by David Kirschner, who produced the first two Child's Play films. Although released only nine months after Child's Play 2, the story takes place eight years following the events of that film, and one month before the events of Bride of Chucky (which was made seven years later). The film follows Andy Barclay (Whalin) now 16, enrolling at Kent Military School. Andy is unknowingly followed by a revived Chucky (Dourif), who sets his sight on a younger kid cadet Ronald Tyler (Sylvers).

After the success of the previous two films, Universal Studios forced Mancini to draft the screenplay for Child's Play 3 in such a short amount of time. A concept featuring "multiple Chuckys" was considered, but was scrapped due to time and budget constraints, although it would be reworked into a later installment Cult of Chucky. Alex Vincent, who played Andy, did not reprise his role due to the film being released in 1991 despite taking place in 1998. Several actors auditioned until Justin Whalin was chosen for the role of Andy.

Released on August 30, 1991, in the United States by Universal Pictures, Child's Play 3 received generally negative reviews from critics and grossed $20.5 million worldwide against a budget of $13 million, being the lowest-grossing film in the series.[3] The film became notorious in the United Kingdom when it was suggested it might have inspired the real-life murder of a British child, James Bulger,[4] suggestions rejected by officers investigating the case.[5][6][7][8]

Plot

Eight years after Chucky's second demise, the Play Pals company resumes manufacturing Good Guy dolls and re-opens their abandoned factory. As Chucky's corpse is being removed from the building, a splash of his blood inadvertently falls into the molten plastic being used to produce the dolls, reviving him in a new body. Chucky tortures and murders Play Pals CEO Mr. Sullivan using various children's toys, and then uses his computer records to locate Andy Barclay.

Now 16, Andy has been sent to Kent Military School after failing to cope in several foster homes. Colonel Cochrane, the school's commandant, advises Andy to forget his "fantasies" about the doll. Andy befriends cadets Ronald Tyler, an 8-year-old boy; Harold Aubrey Whitehurst, a cowardly young man; and Kristin De Silva, for whom he develops romantic feelings. He also meets Brett C. Shelton, a sadistic lieutenant colonel who routinely bullies the cadets.

Tyler is asked to deliver a package to Andy's room. Tyler realizes that the package contains a Good Guy doll and takes it to the school's weapons armory to open it. Chucky bursts from the package and is incensed to find Tyler instead of Andy. However, remembering he can possess the first person who learns his true identity, he tells Tyler his secret. Before Chucky can enact the voodoo soul-swapping ritual to possess Tyler, Cochrane interrupts them and confiscates the doll, throwing it into a garbage truck. Chucky escapes by luring the driver into the truck's compactor and crushing him to death.

That night, Chucky attacks Andy and tells him his plans for taking over Tyler's body. Before Andy can fight back, Shelton comes in and takes the doll from him. Andy then sneaks into Shelton's room to recover it; Shelton awakens to confront him, only to find that Chucky has vanished. Suspecting the doll was stolen, Shelton forces all the cadets to do exercises as punishment. Chucky attempts to possess Tyler again, but they are interrupted by De Silva and fellow cadet Ivers. Later, a knife-wielding Chucky surprises Cochrane, unintentionally shocking him into a fatal heart attack. The next morning, Andy tries to convince Tyler that Chucky is evil, but Tyler refuses to believe him. Meanwhile, Chucky kills the camp barber Sergeant Botnick by slashing his throat with a straight razor. Whitehurst witnesses Botnick's murder and flees in terror.

Despite Cochrane's death, the school's annual war games are ordered to proceed as planned, with cadets divided between a "Red Team" and "Blue Team". Andy, Whitehurst and Shelton are both on the Blue Team. Chucky secretly replaces the paint bullets of the Red team with live ammunition. When the simulation begins, Chucky lures Tyler away from his team. Finally realizing that Chucky is evil, Tyler stabs him with a pocket knife and flees to find Andy. Chucky then attacks De Silva and holds her hostage, forcing Andy to exchange Tyler for De Silva. The Blue team and Red team arrive on the scene and open fire; Shelton is killed by a bullet from the Red team while Tyler escapes in the chaos. Chucky tosses a grenade at the quarrelling cadets; Whitehurst leaps on top of the grenade, sacrificing himself to save the others.

Tyler flees to a nearby carnival where Chucky kills a security guard and captures him again. Andy and De Silva arrive soon after and take the security guard's gun. They follow Chucky and Tyler into a horror-themed roller-coaster. Chucky wounds De Silva; she gives Andy the gun and tells him to save Tyler. Andy pursues Chucky deeper into the ride and repeatedly shoots him, saving Tyler. Chucky revives and attacks again. In the struggle, Andy manages to throw him into a massive metal fan, shredding his body apart and finally killing him. De Silva is rushed to the hospital while Andy is taken away by police for questioning.

Cast

- Justin Whalin as Andy Barclay

- Perrey Reeves as Kristin de Silva

- Jeremy Sylvers as Ronald Tyler

- Travis Fine as Cadet Lieutenant Colonel Brett C. Shelton

- Dean Jacobson as Harold Aubrey Whitehurst

- Brad Dourif as the voice of Chucky

- Peter Haskell as Sullivan

- Dakin Matthews as Colonel Francis Cochrane

- Andrew Robinson as Sergeant Botnick

- Burke Byrnes as Sergeant Clark

- Matthew Walker as Ellis

- Donna Eskra as Jackie Ivers

- Edan Gross as the voice of Good Guy doll

- Terry Wills as Garbage Man

- Richard Marion as Patterson

- Laura Owens as Lady Executive

- Ron Fassler as Petzold

- Michael Chieffo as Security Guard

- Henry G. Sanders as Major

- Nigel Mansell as Himself

- Gerhard Berger as Himself

Production

Universal Studios had Don Mancini begin writing the third installment for the series before Child's Play 2 was released, causing pressure on him to draft a storyline on such a tight schedule.[9] The film was formally greenlit after the successful release of its predecessor with a release date nine months away.

Mancini initially wanted to introduce the concept of "multiple Chuckys" in the movie, but due to budget constraints the idea was eventually scrapped.[10] Mancini later used this concept for the 2017 sequel Cult of Chucky. It also was intended to open with a scene of a security guard portrayed by John Ritter frightening off a group of trespassing children at the Good Guys factory by telling them scary stories about Chucky. After Mancini decided to make Andy Barclay 16 years old, he considered recasting the role with Jonathan Brandis before hiring Justin Whalin. Before Jack Bender became director, Mancini wanted to hire Peter Jackson.[11]

Principal photography began on February 4, 1991, at the Kemper Military School in Boonville, Missouri. Further filming took place in California at Los Angeles and the Universal Studios Lot in Universal City. The carnival scenes were filmed in Valencia, California.[1] The puppeteers made the doll speak using computer technology to control its mouth movements to align with Dourif's prerecorded dialogue.[11][1] N. Brock Winkless IV returned to work as one of Chucky's puppeteers,[12] as did Van Snowden.

Reception

Box-office

Child's Play 3 opened in second place at the US box office behind Dead Again with $5.7 million over the 4-day 1991 Labor Day weekend, which the Los Angeles Times called "slow numbers", however, it was the top-grossing Labor Day opening at the time, beating the record $4.6 million held by Bolero since 1984.[13][14] It finished its theatrical run with $15 million in the US and Canada, and a total of $20.5 million worldwide.[2]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 19% based on reviews from 16 critics, and an average rating is 4.20/10, making it the poorest reviewed film in the series on the site.[15] On Metacritic it has a score of 27% based on reviews from 13 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews".[16]

Chris Hicks of the Deseret News called it "perverse" and criticized the film's plot.[17] Caryn James of The New York Times called the Chucky doll "an impressive technological achievement" but said the film "misses the sharpness and dark humor" of the original film.[18] Variety called it a "noisy, mindless sequel" with good acting.[19] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post wrote, "Chucky himself is an animatronic delight, but one suspects the film's energies and budget have all been devoted to what is essentially a one-trick pony."[20] Stephen Wigle of The Baltimore Sun called it "fun for any fan of the slasher genre".[21]

Series creator Don Mancini said that this was his least favorite entry in the series, adding that he ran out of ideas after the second film.[22] He elaborated further in 2013 stating that he was not pleased with the casting, feeling Jeremy Sylvers was too old for the role of Tyler and Dakin Matthews was not the "R. Lee Ermey" archetype he was looking for in Colonel Cochrane.[10] Mancini would not make another entry in the Chucky series until seven years later, with Bride of Chucky. In a 2017 interview, director Jack Bender also dismissed the film by calling it "kinda silly".[citation needed]

In the years since its release, Child’s Play 3 has received a critical re-evaluation from retrospective critics and fans.[23][24][25] Its setting, tone, climax and Dourif’s performance has been praised and is considered by some to be one of the more superior films in the series, being compared to later entries like Seed of Chucky (2004).[26][27]

In October 2021, Perrey Reeves, who plays De Silva in the film, expressed interest in reprising her role as the character in the TV series Chucky.[28]

Awards

This film was nominated at the Saturn Award as Best Horror Film and Justin Whalin was nominated as Best Performance by a Younger Actor for his performance in this film.[29] Andrew Robinson was nominated as Best Supporting Actor at the Fangoria Chainsaw Award.

Home media

Child's Play 3 was originally released on home video in North America on March 12, 1992 and on DVD on October 7, 2003.[citation needed] It was also released in multiple collections, including The Chucky Collection (alongside Child's Play 2 and Bride of Chucky), released on October 7, 2003;[30] Chucky – The Killer DVD Collection (alongside Child's Play 2, Bride and Seed of Chucky), released on September 19, 2006;[31] Chucky: The Complete Collection (alongside Child's Play 1 and 2, Bride, Seed and Curse of Chucky), released on October 8, 2013;[32] and Chucky: Complete 7-Movie Collection (alongside Child's Play 1 and 2, Bride, Seed, Curse and Cult of Chucky), released on October 3, 2017.

Child's Play 3 was released on 4K Ultra HD by Scream! Factory on August 16, 2022. This release included a new 4K scan from the original camera negative, a new Dolby Atmos track and several interviews recorded in 2022 with creator Don Mancini, actress Perry Reeves, executive producer David Kirschner, executive producer Robert Latham Brown, actor Michael Chieffo, makeup artist Craig Reardon and production designer Richard Sawyer.[33]

The murder of James Bulger

A suggested link with the film was made after the murder of James Bulger. The killers, who were ten years old at the time, were said to have imitated a scene in which one of Chucky's victims is splashed with blue paint. Psychologist Guy Cumberbatch stated, "The link with a video was that the father of one of the boys – Jon Venables – had rented Child's Play 3 some months earlier."[34] However, the police officer who directed the investigation, Albert Kirby, found that the son, Jon, was not living with his father at the time and was unlikely to have seen the film. Moreover, the boy disliked horror films—a point later confirmed by psychiatric reports. Thus the police investigation, which had specifically looked for a video link, concluded there was none.[citation needed] However, the judge, Justice Morland, said in his comments that the murder had "some striking similarities" to the film and that "grave crimes by young children" could be caused by reasons including exposure to violent video films "including possibly Child's Play 3". Following the trial, the Association of Video Retailers in the UK recommended that its members voluntarily remove the trilogy from their shelves.[35]

The film remained controversial in Europe, and both Sky Television in the United Kingdom and Canal+ in Spain refused to broadcast the film as regular programming[1] and the case led to new legislation for video films.[36]

Other media

Novelization

A tie-in novel was later written by Matthew J. Costello. Just like Child's Play 2, this novel had some of the author's own inclusions. In the beginning (adapted from an earlier draft of the screenplay), in the Play Pals factory, a rat scours for food and, smelling blood within the plastic, chews on Chucky's remains. Blood then leaks out of the remains and somehow leaks onto another doll.

Chucky's death in this book is also different. In the novel, while defending Tyler on an exterior ride, Andy grapples with Chucky before finally shooting him several times, causing the doll's body to fall to the ground, and Andy watches the head shatter to blood, metal and plastic.

Sequels

The film was followed by Bride of Chucky in 1998, Seed of Chucky in 2004, Curse of Chucky in 2013, Cult of Chucky in 2017, and the TV series Chucky in 2021.

Halloween Horror Nights

In 2009, the climax of Child's Play 3 received its own maze at Universal Studios' Halloween Horror Nights, entitled Chucky's Fun House.

This is not the first time Chucky has been featured in Halloween Horror Nights. Since 1992, Chucky has starred in his shows, Chucky's In-Your-Face Insults and Chucky's Insult Emporium. Curse of Chucky also received its own Scarezone in the 2013 lineup.[37]

See also

- Dolly Dearest, another 1991 horror movie about a killer doll released two months after Child's Play 3

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Child's Play 3 (1991)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Child's Play 3". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "How Much Did Child's Play Cost to Make?". Screen Rant. June 19, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Kenneth (2005). Moral Panics. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 9781134811625.

- ^ "No conclusive link between videos and violence". BBC. January 7, 1998. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Kirby, Terry; Foster, Jonathan (November 26, 1993). "Video link to Bulger murder disputed". The Independent. London. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Elstein, David (December 22, 1993). "Demonising a decoy". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "U.K. Proposes Rules, Penalties On Rental Of Violent Videos". Billboard. New York. April 23, 1994.

- ^ "10 Behind-The-Scenes Facts About The Making Of Child's Play 3". ScreenRant. September 5, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Bibbiani, William. The Chucky Files – Don Mancini on Child's Play 3 (1991). Retrieved December 10, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "10 Behind-The-Scenes Facts About The Making Of Child's Play 3". ScreenRant. September 5, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Cheng, Cheryl (July 30, 2015). "N. Brock Winkless IV, the Puppeteer of Chucky in 'Child's Play,' Dies at 56". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Fox, David J. (September 4, 1991). "Weekend Box Office : 'Dead' Enlivens Labor Day Business". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "Top-Ten Labor Day Openings". Daily Variety. August 30, 1994. p. 40.

- ^ "Child's Play 3 (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. August 30, 1991. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ "Child's Play 3". Metacritic. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Child's Play 3". Deseret News. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ James, Caryn (August 30, 1991). "Child's Play 3". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "Child's Play 3". Variety. December 31, 1990. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (August 30, 1991). "'Child's Play 3'". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Wigle, Stephen (August 30, 1991). "'Child's Play 3': Chucky's back--more amusing and disturbing than ever". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Zupan, Michael (October 11, 2013). "Chucky: The Complete Collection (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Eschberger, Tyler (January 18, 2023). "'Child's Play 3' – Let's Give Some Love to the Franchise's Most Unloved Movie". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Ben (October 23, 2019). "Child's Play 3 (1991) Review". Distinct Chatter. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Lolo. "Movie Review: "Child's Play 3" (1991)". Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Roberts, Daniel (April 13, 2022). "Every 'Child's Play' Movie Ranked From Worst to Best". Inside the Magic. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Goodwin, Jess (October 15, 2022). "I Ranked The "Child's Play" Movies From Least Favorite To Favorite And Want To See If You Agree". BuzzFeed. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Luu Sapphire (October 2, 2021). Perrey Reeves, aka Kristin De Silva from Child's Play 3, wants to return to the Chucky franchise!!!!. Retrieved September 24, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA (1992)". IMDb. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (September 8, 2006). "Double Dip Digest: Child's Play". IGN. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Jane, Ian (September 21, 2006). "Chucky: The Killer DVD Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Zupan, Michael (October 11, 2013). "Chucky: The Complete Collection (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Child's Play 3 [Collector's Edition] + Exclusive Poster – UHD/Blu-ray :: Shout! Factory". shoutfactory.com. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ^ Faux, Ronald; Frost, Bill (November 25, 1993). "Boys guilty of Bulger murder". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 26, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Harrison, Amanda (December 3, 1993). "Trial sparks debate on video violence". Screen International. p. 23.

- ^ Morrison, Blake (February 6, 2003). "Life after James". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "Universal Studios Halloween Horror Nights Introduces Chucky and Purge Scarezone". Fearnet.com. August 15, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

External links

- 1991 films

- 1991 horror films

- 1991 black comedy films

- 1990s teen horror films

- 1990s serial killer films

- 1990s slasher films

- American sequel films

- American slasher films

- American serial killer films

- American teen horror films

- American black comedy films

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about the military

- Films set in Chicago

- Films set in Missouri

- Films shot in Missouri

- Films shot in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Child's Play (franchise) films

- Films set in 1998

- Universal Pictures films

- Films directed by Jack Bender

- Films with screenplays by Don Mancini

- Films set in amusement parks

- 1991 directorial debut films

- 1990s American films

- Films about Voodoo

- Films scored by Cory Lerios

- Films scored by John D'Andrea

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language horror films

- English-language crime films

- Saturn Award–winning films