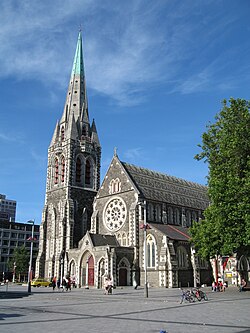

Christ Church Cathedral, Christchurch

| ChristChurch Cathedral | |

|---|---|

ChristChurch Cathedral in Cathedral Square (2006) | |

| |

| 43°31′52″S 172°38′13″E / 43.531°S 172.637°E | |

| Location | Christchurch Central City |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | christchurchcathedral.co.nz |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Category I |

| Designated | 7 April 1983 |

| Architect(s) | George Gilbert Scott Benjamin Mountfort |

| Architectural type | Gothic Revival style |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Peter Carrell[1] |

| |

| Designated | 7 April 1983[2] |

| Reference no. | 46 |

ChristChurch Cathedral, also called Christ Church Cathedral and (rarely) Cathedral Church of Christ,[2] is a deconsecrated Anglican cathedral in the central city of Christchurch, New Zealand. It was built between 1864 and 1904 in the centre of the city, surrounded by Cathedral Square. It became the cathedral seat of the Bishop of Christchurch, who is in the New Zealand tikanga of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia.

Earthquakes have repeatedly damaged the building (mostly the spire): in 1881, 1888, 1901, 1922, and 2010. The February 2011 Christchurch earthquake destroyed the spire and the upper portion of the tower, and severely damaged the rest of the building. A lower portion of the tower was demolished immediately following the 2011 earthquake to facilitate search and rescue operations. The remainder of the tower was demolished in March 2012. The badly damaged west wall, which contained the rose window, partially collapsed in the June 2011 earthquake and suffered further damage in the December 2011 earthquakes.[3] The Anglican Church decided to demolish the building and replace it with a new structure, but various groups opposed the church's intentions, with actions including taking a case to court. While the judgements were mostly in favour of the church, no further demolition occurred after the removal of the tower in early 2012. Government expressed its concern over the stalemate and appointed an independent negotiator and in September 2017, the Christchurch Diocesan Synod announced that ChristChurch Cathedral will be reinstated[4] after promises of extra grants and loans from local and central government.[5] By mid-2019 early design and stabilisation work had begun.[6]

Since 15 August 2013 the cathedral community has worshipped at the Cardboard Cathedral.

History

Construction

Construction of the cathedral took 40 years, with construction paused at times due to a lack of funding.

The origins of the cathedral date back to the plans of the Canterbury Association, which aimed to build a city around a central cathedral and college in the Canterbury region, based on the English model of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. In the original survey of central Christchurch (known as the Black Map), undertaken in 1850, it was envisaged for the college and cathedral to be built in Cathedral Square.[7] The area set aside for the college was found to be insufficient, and Henry Sewell suggested in June 1853 to move it to land reserved for the Christchurch Botanic Gardens.[8] This transaction was formalised through The Cathedral Square Ordinance 1858 passed by the Canterbury Provincial Council in October 1858.[9] The ordinance allowed for Colombo Street to go through the middle of Cathedral Square at a legal width of 1.5 chains (99 ft; 30 m) with the cathedral to the west.[9][10]

Henry Harper, the first Bishop of Christchurch, arrived in 1856 and began to drive the cathedral project.[11][12] Most Christian churches are oriented towards the east,[13][14] and to comply with this convention, Harper lobbied to have the eastern side of Cathedral Square to be used. That way, the main entrance would face Colombo Street, resulting in praying towards the east in line with custom.[15] The Cathedral Square Amendment Ordinance 1859, formalised this change.[16][17]

In 1858 the project was approved by the diocese[citation needed] and a preliminary design was commissioned from George Gilbert Scott, a prolific British architect known for his Gothic Revival churches and public buildings.[17] Scott never visited Christchurch, but handed over the oversight of the project to Robert Speechly.[11] Scott had earlier designed a timber church, the plans for which arrived with the Reverend Thomas Jackson in 1851, but were never used.[2]

Just before work on the foundations began, the alignment of Colombo Street through Cathedral Square was changed by introducing a curve towards the west, with the western side of the legal road having a radius of 3 chains 75 links (75 m),[18] to place the cathedral slightly further west, making its tower visible along Colombo Street from a distance.[15]

Scott's original design was for a Gothic-style cathedral, primarily constructed in oak timber to make it resistant to earthquakes.[19] Bishop Harper and the Cathedral Commission, however, argued that the cathedral should be built from stone. Scott's revised plans received in 1862, showed an internal timber frame with a stone exterior. Superintendent James FitzGerald suggested an iron or steel frame to reduce cost, but Harper rejected this as he believed some bishops refused to consecrate iron-framed churches.[19] Continuing pressure for an all-stone church, and concerns over the lack of timber in Canterbury, led to Scott supplying alternative plans for a stone arcade and clerestory. These plans arrived in New Zealand in 1864.[2]

The cornerstone was laid on 16 December 1864,[20] and by April 1865 the foundations had largely been completed,[21] but work stopped soon after due to a lack of funds. The square was essentially abandoned for the next 8 years, becoming overgrown with grass.[22] Speechly's contract expired in 1868, and he left for Melbourne.[22] Commentators of the time voiced their disappointment at the lack of progress. The novelist Anthony Trollope visited in 1872 and referred to the "vain foundations" as a "huge record of failure",[11] describing the square as a "large waste space" with "not a single brick or single stone above the level of the ground".[23]

In 1873 a new resident architect, New Zealander Benjamin Mountfort, took over and construction began again. Mountfort had been passed over to manage the project when it was first mooted 10 years previously.[24] The reasons at the time had been that the bishop wanted an English architect, with Harper describing Mountfort's other buildings as lacking "taste and strength of composition".[25] During the intervening decade, however, Mountfort had proven himself quite capable with projects including the Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings and Canterbury Museum.[24] Mountfort adapted Scott's design, including: adding balconies and pinnacles to the tower; adding porches to the north and west; increasing the height of the south porch; extending the run of interior columns; and decorative details such as the font, pulpit and stained glass.[11][26] He also rearranged the pattern of the roof slates.[25] Banks Peninsula totara and matai timber were used for the roof supports.[27] By the end of 1875 the walls were 23 feet (7.0 m) high, and the first service was held within them.[26]

The nave, 100 foot (30 m) long, and tower were consecrated on 1 November 1881.[27] In 1894, Elizabeth, the widow of Alfred Richard Creyke, arranged for the western porch to be built in his memory.[28] When Mountfort died in 1898, his son, Cyril Mountfort (1852–1920), took over as supervising architect.[29] He oversaw the completion of the chancel, transept and apse, construction of which began in 1900[30] and was finished by 1904.[31] The Christchurch Beautifying Society planted two plane trees to the south in 1898.[27]

The Rhodes family, who arrived in Canterbury before the First Four Ships, provided funds for the tower and spire. Robert Heaton Rhodes sponsored the tower in memory of his brother George[32] and the spire was added by George's children. The steps of the wooden lectern were sponsored by George's children.[33] The family donated eight bells[34] and a memorial window, and paid for renovations as required.

The spire reached to 63 metres (207 ft) above Cathedral Square, and public access provided for a good viewpoint over the centre of the city. The spire was damaged by earthquakes on four occasions. The tower originally contained a peal of ten bells, cast by John Taylor & Co of Loughborough, and hung in 1881. The original bells were replaced in 1978 by 13 new bells, also cast at Taylors.[35]

In 1999 the cathedral underwent significant earthquake strengthening, which reinforced the roof and the walls.[36] This was credited with keeping the building fabirc intact during the major earthquakes of the 2010s, and saving the lives of people within the building during aftershocks.[37]

Heritage listing

On 7 April 1983, the church was registered by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust as a Category I historic place, registration number 46. It is the only church designed by Scott in New Zealand. Its design was significantly influenced by Mountfort. It is a major landmark and tourist attraction, and for many it symbolises the ideals of the early settlers. There are numerous memorial tablets and memorial windows, acting as a reminder of the early people and the region's history.[2] For example, a list of the 84 members of the Canterbury Association was first compiled for volume one of A History of Canterbury. Even before the history was published in 1957, a memorial tablet of the members was installed in the western porch in 1955.[38]

Visitor centre

During the 1990s, largely under the guidance of dean John Bluck, the cathedral underwent redevelopment and renovation. The operation and maintenance of the cathedral was costing close to NZ$1,000,000 a year, and it was decided that money from visiting tourists could be captured to meet the shortfall.[39] The decision to add a visitor centre was controversial; some objected to the idea of operating a trade business in a church on religious grounds.[40] The design of the new building was also a point of contention, with the Historic Places Trust threatening to block any alteration of the cathedral.[40]

The final design was a two-storey building on the north side of the cathedral, partially buried underground to minimise the impact on the profile of the cathedral.[41] The profile of the building was designed to complement that of the neo-Gothic cathedral. The centre was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth on 4 November 1994.[42]

Interior

The high altar's reredos was made from kauri planks from an old bridge over the Hurunui River and includes six carved figures: Samuel Marsden, Archdeacon Henry Williams, Tāmihana Te Rauparaha, Bishop George Selwyn, Bishop Henry Harper and Bishop John Patteson.[43]

The pulpit, designed by Mountfort, commemorates George Selwyn, the first and only Bishop of New Zealand. Mountfort also designed the font, which was donated by Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Dean of Westminster in memory of his brother, Captain Owen Stanley of HMS Britomart, who arrived in Akaroa in 1840.[35]

The cathedral contains the throne and memorial to Bishop Harper, the first Bishop of Christchurch and the second Primate of New Zealand, who laid the foundation stone in 1864 and preached at the consecration service in 1881.[44] In the west porch are stones from Canterbury Cathedral, Christchurch Priory, Tintern Abbey, Glastonbury Abbey, Herod's Temple, St Paul's Cathedral and Christ Church, Oxford.[45]

The north wall includes a mural dado of inlaid marble and encaustic tiles, donated by the Cathedral Guild in 1885, which includes fylfot motifs. A memorial window above the mural was donated in memory of Sir Thomas Tancred, Bt (1808–1880).[35][46]

On the south side of the nave there is a Watts-Russell Memorial Window in memory of her first husband.[47]

The Chapel of St Michael and St George was opened by Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg, VC, the Governor-General, on Remembrance Day (6 November 1949) and dedicated to Archbishop Campbell West-Watson.[48]

Rose window

The rose window was designed by Mountfort, and was presented by Leonard Harper and his wife Joanna.[49] The window featured 31 sections and 4000 pieces of stained-glass,[49] made in London in 1881 by glass artisans Clayton and Bell.[50] The window was installed at the western end of the nave, 20 metres (66 ft) above the main door.[50] The window had a diameter of 7.5 metres (25 ft).[51] The artwork depicts the hierarchy of angels orbiting around the Lamb of God.[50]

During an earthquake in June 2011, the rose window collapsed onto a roof below, and was destroyed. The fragments were carefully recovered, and in 2022 they were sent to a local stained-glass artisan, Graham Stewart, for restoration. Less than 10% of the original window could be salvaged, leaving Stewart to recreate much of the lost artwork. In June 2024, the restoration was completed.[50]

Earthquake damage

The Canterbury region has experienced many earthquakes and, like many buildings in Christchurch, the cathedral has suffered earthquake damage.

Early earthquakes

- 1881

- A stone was dislodged from the finial cap of the spire, immediately below the terminal cross, within a month of the cathedral's consecration.[52]

- 1888

- Approximately 8 metres of stonework fell from the top of the spire as a result of 1 September 1888 North Canterbury earthquake. The stone spire was replaced.[52] The repair was completed in August 1891, with Bishop Julius hoisted to the top of the spire to place the last stone.[53]

- 1901

- The top of the spire fell again as a result of 16 November 1901 Cheviot earthquake. In 1902 it was replaced with a more resilient structure of Australian hardwood sheathed with weathered copper sheeting, with an internal mass damper.[52] The repairs were funded by the Rhodes family.[54]

- 1922

- One of the stone crosses fell during 25 December 1922 Motunau earthquake.[55]

Modern earthquakes

- 2010

- 4 September 2010 Canterbury earthquake caused some superficial damage and the cathedral was closed for engineering inspections until 22 September 2010, when it was deemed safe to reopen.[56] Further damage was sustained in the Boxing Day aftershock on 26 December.[57]

- 2011 February

- The 6.3-magnitude earthquake on 22 February 2011 left the cathedral damaged and several surrounding buildings in ruins. The spire was completely destroyed, leaving only the lower half of the tower standing. While the walls and roof remained mostly intact, the gable of the west front sustained damage and the roof over the western section of the north aisle, nearest the tower, collapsed from falling tower debris.[58] Inspection showed that the pillars supporting the building were severely damaged; further investigation of damage to the foundations was anticipated, to determine whether the cathedral could be rebuilt on the site.[59]

- Preliminary reports suggested that as many as 20 people had been in the tower at the time of its collapse,[60][61][62] but a thorough examination by Urban Search and Rescue teams found no bodies.[63]

- 2011 June

- The cathedral suffered further damage on 13 June 2011 from the 6.4-magnitude June 2011 Christchurch earthquake with the rose window in the west wall falling in[64] and raised the question of "... whether the cathedral needed to be deconsecrated and demolished".[65]

- 2011 December

- The cathedral suffered further damage from the swarm of earthquakes on 23 December, the largest measuring 6.0 on the Richter magnitude scale, during which what remained of the rose window collapsed.[66]

Proposed demolition

The major aftershocks of 23 June 2011 caused such significant damage to the cathedral that demolition began to look certain. In October 2011 Bishop Victoria Matthews announced that the structure would be deconsecrated and at least partially demolished.[67] The cathedral was deconsecrated on 9 November 2011 at a restricted ceremony in front of the ruined building.[68][69]

The relationship between bishop Matthews and dean Peter Beck became strained through this period, and Beck resigned as dean in December 2011.[70] He subsequently ran for the Christchurch City Council, winning the seat for Burwood-Pegasus ward.[70] Beck was replaced by Lynda Patterson.[71]

On 2 March 2012, Matthews announced that the building would be demolished.[72] She questioned the safety of the building and stated that rebuilding could cost NZ$50,000,000 more than insurance would cover and that a new cathedral would be built in its place.[73] The decision was supported by 70 local Christchurch churches and Christian groups.[74] In late March 2012, demolition began and the scope involved removing the windows and demolishing the tower.[75] By 23 April 2012, the stained glass of nine windows had been removed and work had begun to pull down masonry from the tower to give safe access to further stained glass windows.[76][77]

In September 2012, Bishop Matthews suggested sharing a new church with the Roman Catholic community, as their place of worship was also damaged in the quakes. The Roman Catholic diocese was not receptive to the idea.[78]

Opposition

Strong opposition to the proposed demolition quickly formed, with heritage groups including the UNESCO World Heritage Centre opposing the action. Those opposed to the demolition included mayor Bob Parker, former mayor Garry Moore,[79] future mayor Lianne Dalziel,[80] Ruth Dyson,[81] Philip Burdon, Jim Anderton, David Carter, broadcaster Mike Yardley, actor David McPhail, and businessmen including Humphry Rolleston and Mike Pero.[82] A local character, the Wizard of New Zealand, made protests calling for the cathedral to be saved.[83] Two opposition groups were set up: Mark Belton organised the Restore Christchurch Cathedral group, and the Great Christchurch Buildings Trust was led by Anderton and Burdon.[84] Burdon pledged NZ$1,000,000 to the restoration, and British businessman Hamish Ogston pledged NZ$4,000,000.[85]

Kit Miyamoto, an American-based structural engineer and expert in earthquake rebuilding, inspected the cathedral after the September 2010 quake. He cited his experience in stating that restoring and strengthening of the building was both "feasible and affordable".[73][86]

In April 2012, a group of engineers from the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering launched a petition seeking the support of 100 colleagues to stop the demolition. They claimed that legal action was also a possibility.[87] In the same month the Restore Christchurch Cathedral Group sought signatures for a petition to save the cathedral.[88][89]

Many locals perceived that the church and government were pressing ahead with demolition, without consultation and against the will of the public.[90] Earthquake recovery minister Gerry Brownlee claimed that nearby property owners wanted the cathedral demolished, but when contacted, they in fact unanimously supported restoration.[91] Support for restoration was not as unanimous in the wider city, however; a Colmar-Brunton poll, organised in 2014 by restoration advocates, showed that 51% of the population wanted the cathedral restored, and only 43% wanted it demolished.[92] Matthew maintained that the future of the cathedral was not a question for all of Christchurch; rather, it was an issue for the church and the people in her diocese.[93] She compared efforts from public interest groups getting involved in the process to "other people designing a person's damaged home".[94]

Legal challenges

On 15 November 2012 the High Court issued an interim judgement[95] granting an application for judicial review made by the Great Christchurch Buildings Trust, challenging the lawfulness of the decision to demolish. This effectively paused demolition, though it did not rule that the demolition was illegal.[96]

In early December 2013, the Supreme Court rejected a further bid to preserve the cathedral.[97] The issue again went to court in May 2014. The court ruled that while there were inconsistencies in the decision-making for the demolition, there was nothing that justified blocking the demolition, and they stay of demolition was lifted.[98] This effectively ended the legal attempts to block the demolition.[99]

In July 2015, Earthquake Recovery Minister Gerry Brownlee wrote to church leaders stating concerns that the lack of progress was holding up the earthquake recovery of the central city.[100] In September, Bishop Matthews announced that the church had agreed to a proposal to an independent government-appointed negotiator between Church Property Trustees and the Great Christchurch Building Trust.[101] No official announcement was made with regards to the appointment due to confidentiality agreements, but it was later revealed that Miriam Dean QC ad been appointed at the independent facilitator.[102] Dean met engineers from all of the interested groups in order to draw a conclusion on the feasability of restoring the cathedral.[102] Her report concluded that the estimated cost of reinstatement was around NZ$105,000,000, and that a proposed contemporary Warren and Mahoney replacement design was likely to cost NZ$66,000,000.[103] On 23 December, Bishop Matthews and Gerry Brownlee announced that the church had agreed to Dean's report that stated that "the building could be reinstated [...] to be 'indistinguishable' from the pre-earthquake building",[104] signalling the end of the impasse. A Cathedral Working Group was set up to consult with all parties about their preferred plan, and in November 2016 they reported their findings. They recommended broad reinstatement of the original building, with some alterations to add new church offices, choir practice rooms, visitor's centre, museum and cafe.[105] On 9 September 2017, the Anglican synod voted with a 55% majority to reinstate the cathedral,[106][107] ending a long and acrimonious dispute about the future of the building. Bishop Matthews resigned in March 2018, shortly after reinstatement work began.[108]

Reinstatement work and abandonment

On 22 August 2018, an agreement was signed that established a company, Christ Church Cathedral Reinstatement Limited, to reinstate the cathedral.[109] Physical works include a combination of repair, restoration and seismic strengthening. The strengthening includes the removal of internal walls so that the rubble fill can be removed and replaced with structural steel or concrete. Base isolation will also be retrofitted. Holmes Consulting has been appointed for structural engineering design, with Warren and Mahoney providing architectural services.[110][111][112] In 2017, the cost of reconstruction was originally estimated at NZ$104,000,000, but by October 2020, when the plans for the reconstruction were released, it had increased nearly 50 percent to NZ$154,000,000.[113] The new plans include a museum and visitor centre, with a cafe, to the north, and an office building with parish hall to the south.[114] The plans required the Citizens' War Memorial to be removed to the site of the old police kiosk; for this to happen the kiosk was demolished.[115] The memorial minus the bronze figures was completed by end of November 2022.[116]

Mothballing

In 2024 the reconstruction cost was revalued to NZ$248,000,000 after a project review. After access was gained to go inside the cathedral the year prior, it was discovered that assumptions about the foundations were wrong. After the review the board decided to "reduce the scope, cost and risk of the project by removing the deep foundation for the tower and the lower courtyard, thus mitigating [the original project's risk]".[117] To reduce the funding gap of over $100 million, in June 2024 the synod decided that it would reduce the cathedral's seismic strengthening.[118] This reduced the total estimate down to NZ$219,000,000, which still represented an NZ$85,000,000 shortfall.[119] In August the government decided that it would not continue to fund the rebuild,[120] and it was decided that restoration would be paused indefinitely.[121] The indefinite pause in restoration was referred to as "mothballing", and involved making the worksite safe, adding a temporary 4-tonne weathertight roof, removing all scaffolding and construction equipment, and pushing the perimeter fence back closer to the building.[122] The site closure work was completed in December 2024,[119] and small visitor tour groups were allowed inside throughout the month.[121] Restoration project leader Mark Stewart stated that the term "mothballing" implied the project had been abandoned, but he disputed that it had been abandoned.[123]

Transitional cathedral

Construction of a transitional cathedral started on 24 July 2012.[124] The site, on the corner of Hereford and Madras Streets, several blocks from the permanent location, was blessed in April 2012.[125] Designed by architect Shigeru Ban and seating around 700 people, it was expected to be completed by Christmas 2012, but the completion date was put back to July and then August 2013 with the dedication service held on 15 August. The materials used in its construction include cardboard tubes, timber and steel.[126]

In November 2012 the diocese began fund raising to pay for the NZ$5 million project, following a High Court judge indicating it may not be legal to build a temporary cathedral using its insurance payout.[127]

Deans

| Period | Dean | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1866–1901 | Henry Jacobs | died 1901 in office |

| 1901–1913 | Walter Harper | died 1930[128] |

| 1913–1927 | Charles Walter Carrington | died 1941[129] |

| 1927–1940 | John Awdry Julius | |

| 1940–1951 | Alwyn Warren | Bishop of Christchurch, 1951 |

| 1951–1961 | Martin Sullivan[130] | Archdeacon of London, 1963; Dean of St Paul's, 1967 |

| 1962–1966 | Allan Pyatt | Bishop of Christchurch, 1966 |

| 1966–1982 | Michael Leeke Underhill | died 1997[131][132] |

| 1982–1984 | Maurice Goodall | Bishop of Christchurch, 1984 |

| 1984–1990 | David Coles | Bishop of Christchurch, 1990 |

| 1990–2002 | John Bluck | Bishop of Waiapu, 2002 |

| 2002–2011 | Peter Beck | |

| For subsequent deans, see Cardboard Cathedral | ||

In late 2011, Dean Peter Beck resigned from his position. Disagreement with Bishop Matthews about the fate of the cathedral was cited as his reason for leaving.[133][70] Beck was succeeded by Lynda Patterson, who served for the first 20 months in an acting position, officially becoming dean on 1 November 2013, the first woman to serve in that role.[134][135] Because ChristChurch Cathedral was inaccessible, Patterson originally worked at St Michael and All Angels and then at the Cardboard Cathedral.[136][137] Patterson died of natural causes on 20 July 2014.[99]

References

Bibliography

- Bohan, Edmund (2022), Heart of the City: The Story of Christchurch's Controversial Cathedral, Christchurch: Quentin Wilson Publishing, ISBN 9780995143845, OCLC 1346311413

- Hight, James; Straubel, C. R. (1957). A History of Canterbury: Volume I : to 1854. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd.

- Reid, Michael (2003). But by my spirit: a history of the charismatic renewal in Christchurch 1960–1985 (PDF) (Thesis). Christchurch: University of Canterbury. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- Sewell, Henry (1980). W. David McIntyre (ed.). The Journal of Henry Sewell 1853–7 : Volume I. Christchurch: Whitcoulls Publishers. ISBN 0-7233-0624-9.

- Wigram, Henry (1916). The Story of Christchurch, New Zealand. Christchurch: Lyttelton Times.

Citations

- ^ "Bishop of Christchurch announcement" (PDF). The Archbishops and Primates of Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Cathedral Church of Christ (Anglican)". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Aftershock swarm rocks Canterbury". 23 December 2011.

- ^ "SYNOD VOTES TO RESTORE CHRISTCHURCH CATHEDRAL". Cathedralconversations. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Stuart, Gabrielle. "Christ Church Cathedral: Cost to ratepayers revealed". Christchurch Star. stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Walker, David (1 May 2019). "Milestone reached in Christ Church Cathedral rebuild as design advisers appointed". Stuff. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Wigram 1916, p. 147.

- ^ Sewell 1980, pp. 306f.

- ^ a b "Session X 1858 (October to December 1858)" (PDF). Christchurch City Libraries. pp. 12–14. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d "Cathedral History". Christchurch Cathedral. Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 32–45.

- ^ "Orientation of Churches". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Peters, Bosco (30 April 2012). "Architectural Design Guidelines 1". Liturgy.co.nz. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Wigram 1916, p. 148.

- ^ "Session XI 1859 (September 1859 to January 1860)" (PDF). Christchurch City Libraries. pp. 7f. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 35.

- ^ "Session XXII 1864 (August to September 1864)" (PDF). Christchurch City Libraries. pp. 8f. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 36.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 43.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 47.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 50.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 53.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 54.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 41.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 58.

- ^ a b c "The Cathedrals of Christchurch", my.christchurchcitylibraries.com, archived from the original on 20 June 2024, retrieved 26 December 2024

- ^ Smith, Jo-Anne. "Watts Russell, Elizabeth Rose Rebecca". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 86.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 91.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 60.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 63.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 61.

- ^ a b c "The Nave – Northern Side / Inside the Cathedral / About / Home". ChristChurch Cathedral. 1 November 1981. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 168.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 226.

- ^ Hight 1957, p. 242.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 160.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 162.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 164.

- ^ "The Apse / Inside the Cathedral / About / Home". ChristChurch Cathedral. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Christchurch Cathedral. "Christchurch Cathedral : Emergency Architecture, New Zealand". christchurchcathedral.co.nz. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "West Porch / Inside the Cathedral / About / Home". ChristChurch Cathedral. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Cyclopedia Company Limited (1903). "Sir Thomas Tancred". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. pp. 372f. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "The Nave – Southern Side". ChristChurch Cathedral. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ "125th Anniversary Campaign / Support Us / Home". ChristChurch Cathedral. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 204.

- ^ a b c d Harper, Jendy (20 June 2024), "Rose again: Christ Church Cathedral's stained glass window restored", Seven Sharp, archived from the original on 18 September 2024, retrieved 26 December 2024

- ^ Lloyd, Emma (4 June 2024), "Restoring illumination to Christ Church Cathedral - Global Philanthropic %", Global Philanthropic, archived from the original on 7 December 2024, retrieved 26 December 2024

- ^ a b c "Cathedral no stranger to quake damage". Brisbane Times. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 220.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 222.

- ^ "Our Shaky History". Environment Canterbury. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Cathedral re-opens after clearance". Anglicantaonga.org.nz. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Christchurch Cathedral. "Christchurch Cathedral : Emergency Architecture, New Zealand". christchurchcathedral.co.nz. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "First look inside collapsed Christchurch Cathedral". bbc.co.uk. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Cathedral damage worse than feared". TVNZ. 28 May 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ "65 dead in devastating Christchurch quake". Stuff. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ Interview, Radio New Zealand, broadcast 22 February 2011.

- ^ "'We may be witnessing New Zealand's darkest day': PM says 65 killed in quake", The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 February 2011, archived from the original on 22 June 2024, retrieved 29 December 2024

- ^ "Christchurch quake: 'No bodies' in cathedral rubble". BBC News. 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Landmarks suffer further damage". stuff.co.nz. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (16 June 2011). "Cathedral future now uncertain". The Press. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "Swarm of quakes hits Christchurch – national". Stuff.co.nz. 23 December 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Charlie Gates (28 October 2011). "Christ Church Cathedral To Be Partially Demolished..." Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Christchurch Cathedral. "Christchurch Cathedral : Emergency Architecture, New Zealand". christchurchcathedral.co.nz. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Bohan 2022, p. 241.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 242.

- ^ "Christ Church Cathedral to be pulled down". Stuff. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b Manhire, Toby (2 March 2012). "Christchurch's quake-damaged cathedral to be demolished". London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Carville, Olivia (3 April 2012). "Church leaders back bishop". The Press. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ Mann, Charley (27 March 2012). "Work on cathedral demolition under way". The Press. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (23 April 2012). "Crane begins tower's demolition". The Press. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 249.

- ^ "Anglicans talk of super-cathedral". 3 News. NZ Newswire. 9 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 254.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 257, 262.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 257.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 243–248.

- ^ "Calls for protection as Cathedral demo crane arrives". The New Zealand Herald. APNZ. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 244-246.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 250.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 238, 248.

- ^ Mann, Charley (17 April 2012). "Cathedral can be saved – engineers". The Press. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Restore the Christchurch Cathedral website". Archived from the original on 22 April 2012.

- ^ Booker, Jarrod (21 April 2012). "Anglicans mum on cathedral petition". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 248.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 251.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 268.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 243, 257.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 260.

- ^ "Interim Judgement of Chisholm J" (PDF). Stuff. High Court of New Zealand. 15 November 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 259.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 261.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 264.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 267.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (18 December 2015). "Christ Church Cathedral announcement expected before Christmas". The Press. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ McClure, Tess; Mathewson, Nicole (3 September 2015). "Church announces new deal for Christ Church Cathedral". The Press. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ a b Bohan 2022, p. 269.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 271.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 270.

- ^ Bohan 2022, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 275.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (9 September 2017). "Cathedral decision will kick-start millions of dollars in donations". The Press. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Bohan 2022, p. 279.

- ^ "Joint venture agreement on Cathedral signed". Christchurch City Council. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Edwardes, Tracey (14 August 2019). "City's Labour of Love". Metropol. pp. 92f. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Milestone reached in Christ Church Cathedral rebuild as design advisers appointed". The Press. 1 May 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "New Zealand: Fixing the ruined Christchurch Cathedral that's frozen in time (02:41)". BBC News. 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Cost to reinstate Christ Church Cathedral goes up by $50m". RNZ News. 22 October 2020. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020.

- ^ Anglican church in New Zealand (20 October 2020). "Plans unveiled for rebuilt Christ Church Cathedral in New Zealand". Anglican Ink. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020.

- ^ "Christchurch Cathedral Citizens War Memorial". 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Cross returns to top of Citizens' War Memorial in Christchurch". The Press. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Christ Church Cathedral rebuild could be 'mothballed' as cost blows out". 1News. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Christ Church Cathedral lowers seismic rating to lessen $114m rebuild shortfall". RNZ. 22 June 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b Law, Tina (15 December 2024), "Christ Church Cathedral mothballing is complete", The Press, archived from the original on 15 December 2024, retrieved 29 December 2024

- ^ "Christ Church Cathedral: No more taxpayer funding for rebuild". RNZ. 9 August 2024. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ a b "A chance for Cantabrians to step inside the now-paused Christ Church Cathedral". The New Zealand Herald. 28 November 2024. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ Leask, Anna (5 April 2024), "Christchurch's Cathedral rebuild to be 'indefinitely mothballed' if new funding not secured by August", NZ Herald, archived from the original on 21 August 2024, retrieved 29 December 2024

- ^ Lam, Sharon (26 December 2024), "How ballooning costs led to the mothballing of the Christ Church Cathedral", The Spinoff, archived from the original on 23 November 2024, retrieved 29 December 2024

- ^ "Digging to start for cardboard cathedral". RNZ. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ "Site blessed for cardboard cathedral". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Mann, Charley (16 April 2012). "Work to start on cardboard cathedral". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Mead, Thomas (29 November 2012). "Fundraiser started for Cardboard Cathedral". 3 News. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "The late Dean Harper". The Evening Post. 7 January 1930. p. 11. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Obituary: Very Rev. C. W. Carrington". The Evening Post. 7 August 1941. p. 11. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Sullivan, Martin Gloster". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Reid 2003, p. 110.

- ^ "Former Dean of Christchurch dies". The Press. 29 April 1997. p. 4.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (9 December 2011). "Dean quit after bishop 'made position untenable'". The Press. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ Crean, Mike (23 November 2013). "Seeking beauty to uplift least, last, lost". The Press. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Dean dies". Timaru Herald. 21 July 2014. p. 1.

- ^ "It's official: Dean Lynda Patterson". Anglican Taonga. 7 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Broughton, Cate (21 July 2014). "Cathedral dean Lynda Patterson dies". The Press. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

External links

- Official website

- Reinstatement project website

- Webb, Carolyn; Dally, Joelle; Mann, Charley (23 February 2011). "The steeple on the skyline, gone after 130 years". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 22 February 2011. News story featuring aerial photo showing fallen spire.

- Anglican cathedrals in New Zealand

- Gothic Revival church buildings in New Zealand

- Churches in Christchurch

- Heritage New Zealand Category 1 historic places in the Canterbury Region

- George Gilbert Scott buildings

- Benjamin Mountfort church buildings

- Churches completed in 1904

- Tourist attractions in Christchurch

- 2011 Christchurch earthquake

- Cathedral Square, Christchurch

- Former Anglican church buildings in New Zealand

- Destroyed churches

- Terminating vistas in New Zealand

- Christianity in Christchurch

- Listed churches in New Zealand

- 1900s churches in New Zealand

- Stone churches in New Zealand