Clun Castle

| Clun Castle | |

|---|---|

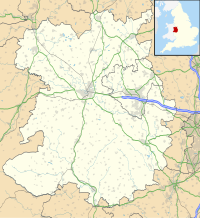

| Shropshire, England | |

Clun Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52°25′18″N 3°02′01″W / 52.4216°N 3.0337°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SO298809 |

| Type | Bailey |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Duke of Norfolk |

| Controlled by | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

Clun Castle is a medieval ruined castle in Clun, Shropshire, England. Clun Castle was established by the Norman lord Robert de Say after the Norman invasion of England and went on to become an important Marcher lord castle in the 12th century, with an extensive castle-guard system. Owned for many years by the Fitzalan family, Clun played a key part in protecting the region from Welsh attack until it was gradually abandoned as a property in favour of the more luxurious Arundel Castle. The Fitzalans converted Clun Castle into a hunting lodge in the 14th century, complete with pleasure gardens, but by the 16th century the castle was largely ruined. Slighted in 1646 after the English Civil War, Clun remained in poor condition until renovation work in the 1890s.

Today the castle is classed as a Grade I listed building and as a Scheduled Monument. It is owned by the Duke of Norfolk, who also holds the title of Baron Clun, and is managed by English Heritage.

Architecture

Clun Castle is located on a bend in the River Clun, overlooking the small town of Clun and its church (on the other side of the river).[1] The river provides natural defences from the north and west, whilst the main keep of the castle stands upon a large motte or mound.[1] Most historians conclude that this is primarily a natural elevation of rock, which has then been cut and scarped into its current, although others argue that it is mostly artificial.[2] Three similar, but less dramatic mounds around the main motte provide the basic structure for the castle defences.[3]

The remains of the 80 ft (24 m) tall, four-storey rectangular great keep are still standing on the north side of the motte. In large part this a typical late Norman keep, 68 by 42 ft (21 by 13 m) wide, similar to those locally at Alberbury, Bridgnorth and Hopton, featuring pilaster buttresses and round-headed Norman windows.[4] Unusually the keep is off-centre, probably to allow the foundations greater reach and avoid placing excessive pressure on the motte – a similar design can be found at Guildford Castle.[5] The ground floor was used for storage, with the upper three storeys for the family's residential use.[6] Each floor had its own large fireplace and five windows.[7] The great keep appears powerful, but was built as a compromise between security and comfort – the building has relatively few arrowslits – many of the externally visible arrowslits are fakes and the building as a whole could easily have been undermined.[6]

On the highest point of the main motte are the remains of one wall of what appears to have been an earlier small square keep, probably dating from the 11th or 12th century. The remains of a bridge, linking the main motte with the south-west mound, can just be seen to the south of this; this bridge would have formed the main route to the town.[8] South of the bridge is the site of the gatehouse, while the foundations of a great round tower can be seen to the south-west. Along the west front are the remains of two solid turrets, built in possible imitation of Château Gaillard. A number of domestic buildings once stood inside the main bailey, including a grange, a stable and a bakehouse.[9] The earthworks of two further bailey walls can be seen on the east side of the castle.[8]

The surrounding grounds around Clun Castle have been extensively developed in the past and a pleasure garden can still be made out in the field beyond the River Clun to the west.[10] To the north-east lies the remains of a fish pond, with a sluice connecting this to the river.[7]

History

11th–12th centuries

Before the Norman invasion, the manor of Clun was owned by Eadric the Wild.[1] The area around Clun was rugged, thinly populated and covered in extensive forests in early medieval times.[11] Clun Castle was originally established by Robert de Say, also known as Picot, an early Norman baron who seized the territory from Edric; Robert built a substantial motte castle with two baileys.[3] Robert held the castle and district from the Earl of Shrewsbury until 1102. After the Shrewsbury rebellion of that year, Robert and his descendants held their castle directly from the Crown.

Picot's daughter married the local Welsh lord, Cadwgan ap Bleddyn. In 1109 Cadwgan was forced out of Powys and it is possible that he lived at Clun Castle during this time.[12] The couple had a son, Owain ap Cadwgan. Picot's son Henry de Say inherited the castle in 1098,[13] with his son, Helias de Say controlling the castle until his death in 1165. Under Helias, the barony of Say was divided in two, with Helias' daughter Isabella de Say receiving an expanded estate centred on Clun, and the more easterly elements of the de Say land, including the future Stokesay Castle, being given to Theodoric de Say.

At around the same time, Henry I established a new castle-guard system at Clun, probably in response to the succession of Welsh attacks in the decades following the rebellion of Gruffudd ap Cynan in 1094.[14] Under the castle-guard system, protecting Clun Castle was undertaken by knights from a group of fiefs stretching eastwards away from Clun and the Welsh frontier, linked in many cases by the old Roman road running alongside the river Clun.[15] Each knight had to conduct forty days of military service each year, probably being called up in a crisis rather than maintaining a constant guard, and were supplemented when required by additional mounted or infantry sergeants.[16] Henry II continued the royal focus on Clun as the regional centre for protecting the border, investing heavily in the castle during 1160–64.[17] The castle could also draw on Welsh feudal service, with twenty-five local Welsh settlements owing the castle military duty.[18]

The area surrounding the castle was now declared a Marcher Barony, known in the 13th century as the Honour of Clun, which meant it was governed by its own, rather than English law, and the Marcher Lord who controlled this section of the Welsh Marches.[19] In particular, the lord of Clun Castle was known for having the right to execute criminals on his own behalf, rather than as the representative of the king; criminals would be taken from as far as Shrewsbury for this punishment to be carried out.[20]

Isabella married William Fitz Alan, the lord of Oswestry. William was another powerful regional lord, and was appointed the High Sheriff of Shropshire by Adeliza of Louvain, the second wife of Henry I.[21] After Henry I's death during the Anarchy, in which England was split between the rival claimants of King Stephen and the Empress Matilda, William declared for the Empress Maud and in 1138 held Shrewsbury Castle for four weeks against Stephen.[22] William escaped before the fall of the city, spending the next fifteen years in exile before the return of Henry II in 1153.[23]

Isabella married twice more after William's death, with her husbands Geoffrey de Vere and William Botorel being lords of Clun Castle by virtue of marriage, but on her death in 1199 the castle passed to her son from her first marriage, the second William Fitz Alan.[24] In doing so, Isabella created the combined lordship of neighbouring Oswestry and Clun, the beginnings of what would become a powerful noble family.[25] William built the tall, off-centre Norman keep that dominates the site today, blending a defensive fortification with the beginnings of a more luxurious style of living. William had been with King Richard I during the building of Château Gaillard in Normandy and it would seem that the distinctive circular towers William built to defend the new keep at Clun were based on those at Gaillard.[citation needed] The result was echoed in Shropshire, on a smaller scale, in the fortified tower-houses at Upper Millichope and Wattlesborough,[6] whilst several generations later the trend would result in Stokesay Castle.[26]

13th century

In the 13th century, Shropshire was in the front line of attempts by Prince Llywelyn the Great to reassert the power of the Welsh principality, aided by the difficult relations that King John enjoyed with the local barons.[27] For many years there was an erroneous story that in 1196 the castle was besieged by the Welsh under Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd, a Prince of the Welsh Kingdom of Deheubarth.[28] This story is a confusion of Colwyn Castle in Radnorshire, which was attacked in 1196, and the Welsh rendition of Clun, Colunwy.

William died in 1210, leaving the castle to his eldest son, another William Fitz Alan. King John, however, demanded a huge fee of 10,000 marks for William to inherit his lands; unable to pay, Clun Castle was assigned to Thomas de Eardington instead.[29] William died shortly afterwards at Easter, 1215, and his brother, John Fitz Alan, a close friend of Llywelyn the Great, promptly took up arms against the king, immediately seizing Clun and Oswestry from royal control.[29] In 1216, King John responded militarily, his forces attacking and burning Oswestry town, before besieging and taking Clun Castle in a surprise attack.[30] John came to an understanding with King John's successor, Henry III in 1217 after finally paying a fine of 10,000 marks.[31]

In 1233–34 during the conflict between King Henry III, the Earl Marshal, and Llywelyn the Great, suspicions were raised again over the loyalty of John Fitzalan, and Clun Castle was garrisoned with royal troops in 1233 to ensure its continued reliability as a key fortress.[30] The castle successfully resisted the attack by Llywelyn that year, although Clun itself was destroyed.[9]

In 1244 John FitzAlan inherited the castle from his father; John also became the de jure Earl of Arundel. The Welsh border situation was still unsettled, and security grew significantly worse in the next few years, as the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd conducted numerous raids into English territories.[32] John's son, another John Fitzalan inherited the castle, marrying Isabella, one of the neighbouring and powerful Mortimer family. In 1272 John died leaving a young son, Richard; during his minority the castle was controlled by Roger Mortimer of Wigmore.[33] A group of commissioners, called in to examine the castle as part of the inquest, noted that the castle was described as "small but strongly built", but in some need of repair, with the bridge and the roof of one of the towers needing particular work.[34]

14th–17th centuries

The invasion of North Wales by Edward I in the 1280s significantly reduced the threat of Welsh invasion and the long-term requirements for strong military fortifications such as Clun Castle.[27] Meanwhile, the FitzAlan family had acquired Arundel Castle by marriage in 1243; their new castle proved to be a much more amenable location for the Earls of Arundel and became their primary residence. By the 14th century Clun Castle had been transformed into a hunting lodge complete with pleasure gardens by the FitzAlan family, who kept a large horse stud at the castle, along with their collections at Chirk and Holt castles.[35]

Richard II made an attempt to break the power of the Arundel family in the area, removing Clun Castle from the Fitz Alan family with the execution of Richard FitzAlan in 1397, granting it to the Duke of York with the intent that it became part of the Earldom of Chester; with the fall of Richard II and the return to favour of Thomas FitzAlan, the castle was restored to the family.[36] There was a resurgence of interest in Clun Castle during the Glyndŵr Rising of 1400–15, with Thomas playing a key role in suppressing the revolt; the castle was refortified and saw some service against the Welsh rebels led by Owain Glyndŵr.[37]

By the 16th century, the antiquarian John Leland observed the increasingly ruined nature of Clun Castle.[25] Philip Howard, the 20th earl of Arundel, died in 1595 whilst under attainment, and James I gave Clun Castle to Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton.[38] The castle was abandoned by the time of the English Civil War of 1642–46 and saw no military action; it was slighted by Parliament, however, in 1646 to prevent any possible use as a fortress.[25] The castle passed through several hands in the coming years, including a period in which it was owned by Clive of India.[37] The 19th century author Sir Walter Scott used Clun Castle as the model for the castle "Guarde Doleureuse" in his medieval novel The Betrothed in 1825.[8]

Today

In 1894, the site was purchased by the Duke of Norfolk, a descendant of the original FitzAlan family.[38] The Duke undertook a programme of conservation on the castle, stabilising its condition.[37] The castle is classed as a Grade I listed building and as a Scheduled Monument.[39] The site is open to the public, managed by English Heritage.

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in Shropshire

- Listed buildings in Clun

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

Bibliography

- Abels, Richard Philip and Bernard S. Bachrach. (eds) 2001 The Normans and their Adversaries at War. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 978-0-85115-847-1.

- Acton, Frances Stackhouse. (1868) The Castles and Old Mansions of Shropshire. Shrewsbury: Leake and Evans.

- Brown, Reginald Allen. (1989) Castles From The Air. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32932-3.

- Burke, John. (1831) A General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerages of England, Ireland, and Scotland. London: Colburn and Bentley.

- Dunn, Alaistair. (2003) The Politics of Magnate Power in England and Wales, 1389–1413. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926310-3.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Eyton, William. (1860) Antiquities of Shropshire, Volume XI. London: John Russell Smith.

- Eyton, William. (1862) "The Castles of Shropshire and its Border." in Collectanea Archæologica: communications made to the British Archaeological Association Vol. 1. London: Longman.

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset. (2005) Castles: England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland: the definitive guide to the most impressive buildings and intriguing sites. Cincinnati: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-2212-3.

- Johnson, Matthew. (2002) Behind the Castle Gate: from Medieval to Renaissance. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25887-6.

- Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2003) Anglo Norman Castles. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Lieberman, Max. (2010) The Medieval March of Wales: The Creation and Perception of a Frontier, 1066–1283. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76978-5.

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896) The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II. New York: Macmillan.

- Owen, Hugh and John Brickdale Blakeway. (1825) A History of Shrewsbury, Vol. I. London: Harding and Lepard.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (1995) English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Suppe, Frederick C. (2001) "The Persistence of Castle Guard in the Welsh Marches and Wales: Suggestions for a Research Agenda and Methodology," in Abels and Bachrach (eds) 2001.

- Suppe, Frederick C. (2003) "Castle guard and the castlery of Clun," in Liddiard (ed) 2003.

Further reading

- Remfry, P.M. Clun Castle, 1066 to 1282. ISBN 1-899376-00-3.

- Summerson, Henry (1993), Clun Castle and Borough: documentary sources (PDF), Hereford: Clun Castle Archive Project

References

- ^ a b c Brown, p. 92.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 211; Mackenzie, p. 113; Brown, p. 92.

- ^ a b Mackenzie, p.131.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 208; Mackenzie, p. 133; Pettifer, p. 211.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 211; Brown, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Emery, p. 586.

- ^ a b Brown, p. 92; Mackenzie, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Mackenzie, p. 133.

- ^ a b Acton, p. 12.

- ^ Johnson, p. 35.

- ^ Emery, p. 472; Lieberman, p.167.

- ^ Stephenson, David (2016). Medieval Powys: Kingdom, Principality, and Lordships, 1132–1293. Woodbridge: Boydell. p. 31. ISBN 9781783271405. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Seton, Robert. An Old Family: Or, The Setons of Scotland and America, Brentano's, 1899, p. 14

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Suppe 2003, p. 217, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Suppe 2003, p. 213.

- ^ Suppe 2003, pp. 219, 220.

- ^ Lieberman, p. 167.

- ^ Suppe, 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Acton, p. 13; Eyton 1860, p. 228.

- ^ Acton, p. 13.

- ^ Owen and Blakeway, p. 77.

- ^ Owen and Blakeway, p. 78.

- ^ Owen and Blakeway, p. 79.

- ^ Brown, p. 93; Suppe, 2001, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Brown, p. 93.

- ^ Emery, p. 576.

- ^ a b Pettifer, p. 208.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 211 believe this however.

- ^ a b Mackenzie, p. 147.

- ^ a b Eyton 1862, p. 45.

- ^ Burke, p. 197.

- ^ Emery, p. 474.

- ^ Eyton 1862, p. 232.

- ^ Eyton 1862, p. 45; Eyton 1860, p. 232; Pettifer, p. 211, Acton p. 12.

- ^ Emery, 688.

- ^ Dunn, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Fry, p. 80.

- ^ a b Mackenzie, p. 132.

- ^ "National Monuments Record, accessed 20 August 2010". Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2010.