Colectomy

| Colectomy | |

|---|---|

Resected colon specimen from a human male with ulcerative colitis | |

| Specialty | General surgery, colorectal surgery |

| ICD-9-CM | 45.8, 45.73 |

| MeSH | D003082 |

Colectomy (col- + -ectomy) is the surgical removal of any extent of the colon, the longest portion of the large bowel. Colectomy may be performed for prophylactic, curative, or palliative reasons. Indications include cancer, infection, infarction, perforation, and impaired function of the colon. Colectomy may be performed open, laparoscopically, or robotically. Following removal of the bowel segment, the surgeon may restore continuity of the bowel or create a colostomy. Partial or subtotal colectomy refers to removing a portion of the colon, while total colectomy involves the removal of the entire colon. Complications of colectomy include anastomotic leak, bleeding, infection, and damage to surrounding structures.

Indications

Common indications for colectomy include:[1][2]

- Colorectal cancer

- Colon polyps not amenable to removal by colonoscopic polypectomy

- Diverticulitis and diverticular disease of the large intestine

- Colon perforation or injury, which can occur as a result of trauma

- Bleeding

- Inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease

- Bowel infarction or ischemia

- Volvulus

- Stricture

- Slow-transit constipation

- Hirschsprung's disease

- Prophylactic colectomy may be indicated in patients with hereditary cancer syndromes such as Familial adenomatous polyposis or Lynch syndrome, and in certain cases of inflammatory bowel disease due to an increased risk of colorectal cancer[3]

Procedure

Pre-operative preparation

Before surgery, patients typically undergo preoperative bloodwork, including a complete blood count and type and screen of blood type. Diagnostic imaging may include colonoscopy or CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis. In cancer patients, lesions are commonly tattooed via colonoscopy before colectomy to give the surgeon an intraoperative visual guide.[1] For non-emergent procedures, patients are typically instructed to follow a clear liquid diet or fast and take a mechanical bowel preparation (oral osmotic agents or laxative) to clear the bowels before surgery.[4][1] Antibiotics may also be prescribed ahead of surgery to reduce risk of post-operative infection.[2]

Operation

Traditionally, colectomy is performed via an abdominal incision, a technique known as laparotomy. Minimally invasive colectomy using laparoscopy is a well-established procedure in many medical centers.[5][6] Robot-assisted colectomy is growing in scope of indications and popularity.[7]

Laparoscopic approach

As of 2012, more than 40% of colon resections in the United States are performed via a laparoscopic approach.[5] For laparoscopic colectomy, the typical operative technique involves 4-5 separate incisions made in the abdomen. Trochars are introduced to gain access to the peritoneal cavity and serve as ports for the laparoscopic camera and other instruments.[8] Studies have proven the feasibility of single port access colectomy, which would require only one small incision, but no clear benefit in terms of outcome or complication rate has been demonstrated.[6][9]

Resection

Before removal, the portion of the bowel to be resected must be freed or mobilized. This is done by dissection and removal of the mesentery and other peritoneal attachments. Resection of any part of the colon entails mobilization and the cutting and sealing, or ligation, of the blood vessels supplying the portion of the colon to be removed.[8] A stapler is typically used to cut across the colon to prevent spillage of intestinal contents into the peritoneal cavity.[10] Colectomy as treatment for colorectal cancer also includes lymphadenectomy, or removal of surrounding lymph nodes, which may be done for staging of the cancer or removal of cancerous nodes.[11] More extensive lymphadenectomy is sometimes accomplished by the removal of the mesocolon, the fatty tissue adjacent to the colon, which contains blood supply, lymphatics, and nerves to the colon.[12][13]

Primary anastomosis vs colostomy

When the resection is complete, the surgeon has the option of reconnecting the bowel by stitching or stapling together the cut ends of the bowel (primary anastomosis) or performing a colostomy to create a stoma, an opening of the bowel to the abdominal wall that provides an alternate exit for the contents of the gastrointestinal tract.[1] When colectomy is performed as part of damage control surgery in life-threatening trauma resulting in destructive colon injury, the surgeon may opt to leave the cut ends of the bowel sealed and disconnected for a short time to allow for further resuscitation of the patient before returning to the operating room for definitive repair (anastomosis or colostomy).[14]

In modern times, surgical staplers are typically used to create colorectal anastomoses, although hand sewn, or sutured, anastomoses are still done today. Studies have shown that differences in rates of anastomotic leak and surgical site contamination for stapled vs. sutured anastomoses are not statistically significant. The increased speed and decreased human variability afforded by stapling make it an attractive option for most surgeons.[15]

Several factors are taken into account when deciding between anastomosis or colostomy, including:

- Urgency of presentation;

- Contamination of the operative field;

- Technical difficulty of the anastomosis;

- Disease severity and stage;

- Physiologic considerations: pelvic floor function, length of bowel remaining;

- Patient factors: social support, socioeconomic status, level of education and health literacy, availability of specialist services, and level of functioning.[16]

Giving a patient a colostomy avoids the risk of a failed anastomosis. Still, it places a societal, psychological, and physical burden on the patient, as a stoma requires special care and consideration.[16]

Complications and risks

All surgery involves a risk of serious complications, including bleeding, infection, damage to surrounding structures, and death. Additional complications associated with colectomy include:

- Damage to adjacent structures such as ureter, bowel, spleen, etc.;

- Need for further operations;

- Conversion of primary anastomosis to colostomy;

- Anastomotic dehiscence or leak;

- Inability to resect colon as intended;

- Cardiopulmonary or other organ failure;

- Death.[1][2]

Anastomotic dehiscence and anastomotic leak

An anastomosis carries the risk of dehiscence or breakdown of the surgical connection. Contamination of the peritoneal cavity with fecal matter as a result of the anastomotic leak can lead to peritonitis, sepsis or death. In patients who underwent colectomy as a treatment for colorectal cancer, an anastomotic leak increases the risk of recurrence of cancer in the same area and reduces survival in the long term. Several factors influence the risk of anastomotic dehiscence, including preservation of blood supply to the cut ends of the bowel, tension on the anastomosis, and the patient's intestinal microbiome, which affects wound healing and potential for surgical site infection.[15]

The use of NSAIDS for analgesia following gastrointestinal surgery remains controversial, given mixed evidence of an increased risk of leakage from any bowel anastomosis created. This risk may vary according to the class of NSAID prescribed.[17][18][19]

Types

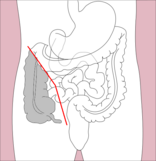

Right hemicolectomy and left hemicolectomy refer to the resection of the ascending colon (right) and the descending colon (left), respectively. When middle colic vessels and transverse colon are also resected, it may be referred to as an extended hemicolectomy.[20] Left hemicolectomy is most commonly indicated for cancer in the splenic flexure or descending colon, diverticular disease of the descending colon, and colovesicular or colovaginal fistulas that develop as a consequence of diverticular disease.[11] The main limitation to performing a left extended colectomy is the difficulty of achieving a colorectal anastomosis afterward. Different techniques, such as Deloyer's or Rosi-Cahil's techniques, have been proposed to solve this issue.[21] Right hemicolectomy is most commonly indicated for masses in the right, or ascending, colon but may also be performed for neoplasms of the cecum or appendix. Right-sided diverticulitis, cecal volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease, and adenomatous polyps are benign conditions that may require right hemicolectomy.[11]

Transverse colectomy involves resection of the transverse colon, the segment of the colon between the hepatic flexure and the splenic flexure. Transverse colectomy is uncommon, as malignant pathologies of the transverse colon typically call for removal of the left colon or right colon as well as the transverse colon due to the variable contributions of the ileocolic, right colic, and left colic blood vessels to lymphatic drainage of the transverse colon. Transverse colectomy is sometimes appropriate for focal benign pathologies such as local inflammation and local trauma or injury such as perforation. [11][22]

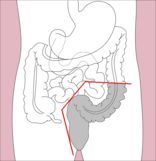

Sigmoidectomy is a resection of the last part of the colon, known as the sigmoid colon, and can include part or all of the rectum (proctosigmoidectomy). Precancerous polyps and sigmoid colon cancer are common indications for sigmoidectomy. Benign indications for sigmoidectomy include diverticular disease, especially when complicated by perforation or fistulae, sigmoid volvulus, trauma, and ischemic or infectious colitis.[11] When a sigmoidectomy is followed by terminal colostomy and closure of the rectal stump; it is called a Hartmann operation. This is usually done out of the impossibility of performing a "double-barrel" or Mikulicz colostomy, which is preferred because it makes "takedown" (reoperation to restore intestinal continuity using an anastomosis) considerably easier.[23]

When the entire colon is removed, this is called a total colectomy, also known as Lane's Operation.[24] Total colectomy may be indicated as a prophylactic measure in certain hereditary polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Total colectomy is also performed for certain forms of inflammatory bowel disease, severe acute colitis, slow-transit constipation, and cancer.[1][11] If the rectum is also removed, it is a total proctocolectomy. Sir William Arbuthnot-Lane was one of the early proponents of the usefulness of total colectomies and was considered a pioneer of colon surgery for routinely performing this procedure. However, his overuse of the procedure called the wisdom of the surgery into question.[25][26]

Subtotal colectomy is resection of part of the colon or a resection of all of the colon without complete resection.[27]

History

The first concepts of colon surgery were thought to have originated in the 15th century as a means to relieve obstructed bowel. The first reported ostomy, performed in 1776 by Pillore of Rouen as an attempt to circumvent blockage caused by a rectal tumor, was done at the insistence of the patient despite opposition from other doctors. While this initial attempt resulted in the death of the patient after only 20 days, subsequent attempts in the following years were more successful.[25] By the mid 1880's, hundreds of colectomies had been performed, with a fatality rate between 50 and 60% (lower for those performed in cases of cancer). Dr. Robert Weir suggested in his 1886 case report on the resection of a rectal tumor that shock from the operation and leakage of intestinal contents both during and after surgery contributed to these numbers.[28] The introduction of exteriorization, where the intestinal segment of interest was brought out of the abdomen and resected after the abdomen was closed around it, decreased the morbidity of the procedure.[25]

Colonic anastomosis

Jean Francois Reybard performed the first successful end-to-end colonic anastomosis following sigmoid colon resection in 1823. Primarily criticized as dangerous, Reybard's procedure went against the standard protocol of the day: resection of the colon with stoma creation and distal closure. However, colonic anastomosis became more acceptable by the end of the 19th century.[25]

Many different methods and materials were used to join ends of the bowel in the early days of intestinal anastomosis, including animal tracheas, artificial pipes made of reed, wood or other materials, cardboard, and rings of silver or wax. Absorbable vegetable plates or sutures became the preference of most by the 1990s.[25] With the advent of the surgical stapler, most surgeons have moved on from hand sewing colorectal anastomoses. However, the dexterity and precision afforded by current robotic surgical technology have spurred new interest in the role of sutured anastomosis.[15]

Minimally invasive colectomy

A report of the first laparoscopically assisted colectomies was published by Jacobs et al. in 1991.[29][30] While initial concerns were raised about the incidence of port site reoccurrence of tumors after laparoscopic colectomy for cancer, it was later found to be similar to that of wound implant of tumor cells as a result of open colectomy for cancer.[29] By the mid-2000s, several studies had been published demonstrating that laparoscopic colectomy was at least as safe as open colectomy and could lead to shorter post-operative recovery times when performed by a skilled surgeon.[29]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Rosenberg, Barry L.; Morris, Arden M. (2010), Minter, Rebecca M.; Doherty, Gerard M. (eds.), "Chapter 23. Colectomy", Current Procedures: Surgery, New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies, retrieved 2024-11-10

- ^ a b c "Colectomy (Bowel Resection Surgery)". Cleveland Clinic. March 22, 2024. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ Kalady, Matthew F.; Church, James M. (November 2015). "Prophylactic colectomy: Rationale, indications, and approach". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 111 (1): 112–117. doi:10.1002/jso.23820. ISSN 0022-4790. PMID 25418116.

- ^ Kumar, Anjali; Kelleher, Deirdre; Sigle, Gavin (2013-08-19). "Bowel Preparation before Elective Surgery". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 26 (3): 146–152. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1351129. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 3747288. PMID 24436665.

- ^ a b Simorov A, Shaligram A, Shostrom V, Boilesen E, Thompson J, Oleynikov D (September 2012). "Laparoscopic colon resection trends in utilization and rate of conversion to open procedure: a national database review of academic medical centers". Annals of Surgery. 256 (3): 462–8. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182657ec5. PMID 22868361. S2CID 37356629.

- ^ a b Kaiser, Andreas M (2014). "Evolution and future of laparoscopic colorectal surgery". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (41): 15119–15124. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15119. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 4223245. PMID 25386060.

- ^ Liu, Hongyi; Xu, Maolin; Liu, Rong; Jia, Baoqing; Zhao, Zhiming (January 2021). "The art of robotic colonic resection: a review of progress in the past 5 years". Updates in Surgery. 73 (3): 1037–1048. doi:10.1007/s13304-020-00969-2. ISSN 2038-131X. PMC 8184527. PMID 33481214.

- ^ a b Briggs, Alexandra; Goldberg, Joel (2017-04-04). "Tips, Tricks, and Technique for Laparoscopic Colectomy". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 30 (2): 130–135. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1597313. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 5380454. PMID 28381944.

- ^ Bucher P, Pugin F, Morel P (October 2008). "Single port access laparoscopic right hemicolectomy" (PDF). International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 23 (10): 1013–6. doi:10.1007/s00384-008-0519-8. PMID 18607608. S2CID 11813538.

- ^ Rattner, David (2016). "Laparoscopic Right Colectomy". Journal of Medical Insight. 2023 (9). doi:10.24296/jomi/125.

- ^ a b c d e f Albo, Daniel; Mulholland, Michael W., eds. (2015). Operative techniques in colon and rectal surgery. Philadelphia Baltimore New York London Buenos Aires Hong Kong Sydney Tokyo: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4511-9016-8.

- ^ Ryu, Hyo Seon; Kim, Hyun Jung; Ji, Woong Bae; Kim, Byung Chang; Kim, Ji Hun; Moon, Sung Kyung; Kang, Sung Il; Kwak, Han Deok; Kim, Eun Sun; Kim, Chang Hyun; Kim, Tae Hyung; Noh, Gyoung Tae; Park, Byung-Soo; Park, Hyeung-Min; Bae, Jeong Mo (April 2024). "Colon cancer: the 2023 Korean clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and treatment". Annals of Coloproctology. 40 (2): 89–113. doi:10.3393/ac.2024.00059.0008. ISSN 2287-9714. PMC 11082542. PMID 38712437.

- ^ Sica, Giuseppe S.; Vinci, Danilo; Siragusa, Leandro; Sensi, Bruno; Guida, Andrea M.; Bellato, Vittoria; García-Granero, Álvaro; Pellino, Gianluca (September 2022). "Definition and reporting of lymphadenectomy and complete mesocolic excision for radical right colectomy: a systematic review". Surgical Endoscopy. 37 (2): 846–861. doi:10.1007/s00464-022-09548-5. ISSN 1432-2218. PMC 9944740. PMID 36097099.

- ^ Chamieh, Jad; Prakash, Priya; Symons, William (December 2017). "Management of Destructive Colon Injuries after Damage Control Surgery". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 31 (1): 036–040. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1602178. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 5787392. PMID 29379406.

- ^ a b c Gaidarski Iii, Alexander A.; Ferrara, Marco (December 2022). "The colorectal anastomosis: a timeless challenge". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 36 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1756510. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 9815911. PMID 36619283.

- ^ a b GlobalSurg Collaborative (February 2019). "Global variation in anastomosis and end colostomy formation following left-sided colorectal resection". BJS Open. 3 (3): 403–414. doi:10.1002/bjs5.50138. ISSN 2474-9842. PMC 6921967. PMID 31891112.

- ^ STARSurg Collaborative (2017). "Safety of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in Major Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Prospective, Multicenter Cohort Study". World Journal of Surgery. 41 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1007/s00268-016-3727-3. PMID 27766396. S2CID 6581324.

- ^ STARSurg Collaborative (2014). "Impact of postoperative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on adverse events after gastrointestinal surgery". British Journal of Surgery. 101 (11): 1413–23. doi:10.1002/bjs.9614. PMID 25091299. S2CID 25497684.

- ^ Bhangu A, Singh P, Fitzgerald JE, Slesser A, Tekkis P (2014). "Postoperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of anastomotic leak: meta-analysis of clinical and experimental studies". World Journal of Surgery. 38 (9): 2247–57. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2531-1. PMID 24682313. S2CID 6771641.

- ^ Martin, Elizabeth A. (2015). Concise medical dictionary. Martin, E. A. (Elizabeth A.) (Ninth ed.). Oxford [England]. p. 347. ISBN 9780199687817. OCLC 926067285.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Segura-Sampedro, J. J.; Cañete-Gómez, J.; Craus-Miguel, A. (2024-07-20). "Modified Rosi-Cahill technique after left extended colectomy for splenic flexure advanced tumors". Techniques in Coloproctology. 28 (1): 87. doi:10.1007/s10151-024-02956-w. ISSN 1128-045X. PMC 11271361. PMID 39031212.

- ^ Herold, Alexander; Lehur, Paul-Antoine; Matzel, Klaus E.; O'Connell, P. Ronan, eds. (2017). Coloproctology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-53210-2. ISBN 978-3-662-53208-9.

- ^ Herold, Alexander; Lehur, Paul-Antoine; Matzel, Klaus E.; O'Connell, P. Ronan, eds. (2017). Coloproctology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-53210-2. ISBN 978-3-662-53208-9.

- ^ Enersen, Ole Daniel. "Lane's operation". whonamedit.com. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ a b c d e Fong, Carmen F.; Corman, Marvin L. (May 2019). "History of right colectomy for cancer". Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. 4: 49. doi:10.21037/ales.2019.05.05.

- ^ Lambert, Edward C. (1978). Modern medical mistakes. Indiana University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-253-15425-5.

- ^ Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL, Easley K (June 1985). "The fate of the rectal stump after subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 28 (6): 394–6. doi:10.1007/BF02560219. PMID 4006633. S2CID 28166296.

- ^ Weir, R. F. (June 1886). "II. Resection of the Large Intestine for Carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 3 (6): 469–489. doi:10.1097/00000658-188603000-00039. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1431489. PMID 17856071.

- ^ a b c Kaiser, Andreas M (2014). "Evolution and future of laparoscopic colorectal surgery". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (41): 15119–15124. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15119. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 4223245. PMID 25386060.

- ^ Jacobs, M.; Verdeja, J. C.; Goldstein, H. S. (September 1991). "Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy)". Surgical Laparoscopy & Endoscopy. 1 (3): 144–150. ISSN 1051-7200. PMID 1688289.

External links

- Lotti M. Anatomy in relation to left colectomy

- Saunders, Brian (2007). "Removing large or sessile colonic polyps" (PDF). OMED 'How I Do It'. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-29. Retrieved 2014-04-28.