Destination Inner Space

| Destination Inner Space | |

|---|---|

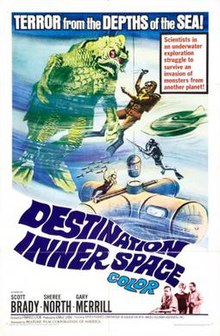

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Francis D. Lyon |

| Written by | Arthur C. Pierce |

| Produced by | Earle Lyon |

| Starring | Scott Brady Gary Merrill Sheree North Wende Wagner |

| Cinematography | Brick Marquard |

| Edited by | Robert S. Eisen |

| Music by | Paul Dunlap |

Production company | Harold Goldman Associates |

| Distributed by | United Pictures Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Destination Inner Space is a 1966 science fiction film produced by Earl Lyon, directed by Francis D. Lyon, written by Arthur C. Pierce, and stars Scott Brady, Gary Merrill, and Sheree North. The film was released to theaters in the US in May 1966 on a double bill with Frozen Alive (1964); its broadcasting rights were pre-sold to television so that some of the licensing fee could be used to finance the film's production.[1][2][3] The story centers on scientists working in a laboratory on the floor of the ocean. They encounter an undersea flying saucer, after which the lab is attacked by a colorful aquatic humanoid monster who they fear may be the first in an alien invasion.

Plot

US Navy Commander Wayne has arrived at Topside, the support vessel for the civilian Institute of Marine Sciences' Sealab, a facility on the ocean floor. He is there because an unidentified object has been spotted circling Sealab. Cmdr. Wayne rides a diving bell down to Sealab, where he meets its director, Dr. LaSaltier and marine biologist Dr. Rene Peron.

During Cmdr. Wayne's arrival, a minisub carrying diver Hugh Maddox and photographer Sandra Welles is approaching the submerged object so as to get a clear photo of it. The object looks like a huge flying saucer, some 50 feet in diameter.

Inside the saucer, a little triangular door opens and a robotic arm pushes a cylinder encased in ice into the saucer's central area. A heat lamp hangs overhead. The ice begins to melt.

Hugh and Sandra take Cmdr. Wayne to the saucer. Inside, the Commander suggests it is a fully-automated spaceship "sent here to study our oceans." He estimates the saucer has about two dozen additional triangular doors. They take the mysterious cylinder back to Sealab.

The Sealab scientists cannot determine what the cylinder is, but Rene is alarmed that it is rapidly growing. When it has doubled in size, it begins emitting a piercing ultrasonic sound. Lab technician Tex runs from the lab but dies from the effects of the sound. Cmdr. Wayne and Hugh arrive and find the lab filled with vapor. The don gasmasks and go inside with fire extinguishers to disperse the vapor, only to discover that the cylinder has burst. They are immediately attacked by the monster that has hatched from the cylinder. Hugh and Cmd. Wayne fight their way out of the lab. The monster escapes into the ocean. It swims up to Topside, kills two crewmen, wrecks the ship's radio, the diving bell controls, and the air supply Topside pumps down to Sealab. Without the air, Sealab's staff can survive for only 12 hours.

The monster re-enters Sealab. Cmdr. Wayne tussles with it, but it escapes again, back into the ocean. Dr. James finds that the monster carries an unidentifiable disease. The Commander worries that large numbers of people will die if more monsters carrying "the plague" emerge. He decides to kill the monster and destroy the saucer.

Cmdr. Wayne lures the monster into a trap he has built - several spearguns set to fire when it triggers tripwires. The monster walks into the trap and is wounded, but again escapes. The Commander, Hugh, and Ellis pursue it. They subdue the monster, take it back to Sealab, and sedate it so it can be taken to the Marine Institute for study.

Hugh and Cmdr. Wayne go to Topside for dynamite to destroy the saucer, then return to Sealab for additional supplies. Meanwhile, inside the saucer, a second triangular door opens and another cylinder is pushed out.

Cmdr. Wayne, Sandra, and Hugh head back to the saucer. Before they can get there, the monster escapes yet again, and swims toward the saucer. it arrives just as the three humans are setting dynamite charges. The monster attacks. Hugh holds it off, allowing Cmdr. Wayne and Sandra to flee, then dies a heroic death in the explosion that obliterates the saucer and kills the monster.

When all equipment is fully operational, Cmdr. Wayne prepares to leave. But before he does, he says that LaSaltier is to give a verbal report about the incident to the president. LaSaltier says he has nothing to report as they have learned nothing with the monster dead and the saucer destroyed. But the Commander sets him straight, telling him they have proven life exists on other planets and that we must learn how to communicate with extraterrestrials. LaSaltier agrees and says that is what he will tell the president.

Cast

- Scott Brady as Cmdr. Wayne

- Sheree North as Dr. Rene Peron

- Gary Merrill as Dr. LaSatier

- Wende Wagner as Sandra Welles

- Mike Road as Hugh Maddox

- John Howard as Dr. James

- William Thourlby as Tex

- Biff Elliot as Dr. Wilson

- Glenn Sipes as Mike

- Richard Niles as Ellis

- Roy Barcroft as Skipper

- Ed Charles Sweeny as Bos'un

- Ken Delo as Radio Man

- Ron Burke as The Thing

- James Hong as Ho Lee

Production

United Picture Corporation's first two films, Castle of Evil and Destination Inner Space, were shot back-to-back in only 14 days. Francis D. Lyon later wrote, "I don't recommend this hurried approach as a practice, because quality has to suffer".[4]

Principal photography of Destination Inner Space began on November 17, 1965 at Producers Studio in Los Angeles. Its production was financed in part by its having been licensed in advance to 44 TV stations by Television Enterprises Corporation (TEC). It was part of a film package that generated licensing fees to TEC of $5 million to $5.5 million. The same package of films was later sold to CBS at an unspecified price.[1]

The film was well-known actor Sheree North's first film in almost a decade. After roles in a number of features, she had been working extensively in TV and on stage, but had not appeared in a motion picture since Mardi Gras (1958).[5]

The film's score is by Paul Dunlap, who composed music for numerous SF films, including I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), and The Angry Red Planet (1959).[6] However, film critic Bruce Elder refers to the music in Destination Inner Space as "mostly hand-me-down work" from The Angry Red Planet.[7]

Release

Destination Inner Space, coupled with Frozen Alive (1964) in the US, had its first reviews appear in trade publications in June 1966.[1]

Home media

The film was released on DVD in 2011 by Cheezy Flicks. As of 2015, the film is available as a streaming video on Amazon.com, and free (to watch) for the members of Amazon's Prime service.[citation needed] May 2024, KL Studio Classics released a high definition print of Destination Inner Space on Blu ray, as part of the Sci-Fi Chillers Collection. The film is accompanied by 2 other films The Unknown Terror and The Colossus of New York.

Reception

In his book A Pictorial History of Science Fiction Films, author Jeff Rovin calls the film "low budget but intriguing," and notes that it "has mediocre performances, but does create an aura of suspense," and "though it is a composite of most every invader-from-space film, it provides ninety minutes of fast-paced entertainment".[8] His final assessment is, "Low budget and average performances do not prevent director Francis Lyon from providing a first-rate entertainment. Nothing profound; just fun".[8]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Destination Inner Space (1966)". American Film Institute. Retrieved 24 March 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Destination Inner Space (1966) - Overview". TCM.com. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ^ Bruce Eder (2015). "Destination-Inner-Space - Trailer - Cast - Showtimes". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ^ P 38 Lyon, Francis D. Two Camera Shooting Can Cut Costs Action Volumes 5-6 Directors Guild of America, 1970

- ^ Kuper, Richard (2010). Fifties Blondes: Sexbombs, Sirens, Bad Girls and Teen Queens. Duncan OK: BearManor Media. pp. 255–257. ISBN 9781593935214.

- ^ "Paul Dunlap". Rate Your Music. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Elder, Bruce. "Destination Inner Space (1966)". Allmovie. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ a b Rovin, Jeff (1975) A Pictorial History of Science Fiction Films, p. 173. Citadel Press, Secaucus, NJ. ISBN 0806505370

External links

- 1966 films

- American science fiction films

- UFO-related literature

- Films directed by Francis D. Lyon

- 1960s science fiction films

- American monster movies

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s monster movies

- United Pictures Corporation

- Films scored by Paul Dunlap

- 1960s American films

- English-language science fiction horror films