Elizabeth Bennet

| Elizabeth Bennet | |

|---|---|

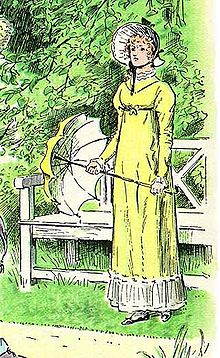

Elizabeth Bennet, a fictional character appearing in the novel Pride and Prejudice, depicted by C. E. Brock | |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Elizabeth, Mrs Darcy |

| Gender | Female |

| Spouse | Mr. Darcy |

| Relatives |

|

| Home | Longbourn, near Meryton, Hertfordshire |

Elizabeth Bennet is the protagonist in the 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. She is often referred to as Eliza or Lizzy by her friends and family. Elizabeth is the second child in a family of five daughters. Though the circumstances of the time and environment push her to seek a marriage of convenience for economic security, Elizabeth wishes to marry for love.

Elizabeth is regarded as the most admirable and endearing of Austen's heroines.[1] She is considered one of the most beloved characters in British literature[2] because of her complexity. Austen herself described Elizabeth as "delightful a creature as ever appeared in print."[3]

Background

Elizabeth is the second eldest of the five Bennet sisters of the Longbourn estate, situated near the fictional market village of Meryton in Hertfordshire, England. She is 20 years old by the middle of the novel.[4] Elizabeth is described as an intelligent young woman, with "a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in anything ridiculous". She often presents a playful good-natured impertinence without being offensive. Early in the novel, she is depicted as being personally proud of her wit and her accuracy in judging the social behaviour and intentions of others.

Her father is a landowner, but his daughters cannot inherit because the estate is entailed upon the male line (it can only be inherited by male relatives). Upon Mr Bennet's death, Longbourn will therefore be inherited by his cousin and nearest male relation, Mr. William Collins, a clergyman for the Rosings Estate in Kent owned by Lady Catherine de Bourgh. This future provides the cause of Mrs Bennet's eagerness to marry her daughters off to wealthy men.

Elizabeth is her father's favourite, described by him as having "something more of quickness than her sisters". In contrast, she is the least dear to her mother, especially after Elizabeth refuses Mr Collins' marriage proposal. Her mother tends to contrast her negatively with her sisters Jane and Lydia, whom she considers superior in beauty and disposition, respectively, and fails to understand her husband's preference. Elizabeth is often upset and embarrassed by her mother's and three younger sisters' impropriety and silliness.

Within her neighbourhood, Elizabeth is considered a beauty and a charming young woman with "fine eyes", to which Mr. Darcy is first drawn. Darcy is later attracted more particularly to her "light and pleasing" figure, the "easy playfulness" of her manners, her personality and the liveliness of her mind, and eventually considers her "one of the handsomest women" in his acquaintance.

Analysis

From the beginning, opinions have been divided on the character. Anne Isabella Milbanke gave a glowing review of the novel, while Mary Russell Mitford criticizes Elizabeth's lack of taste.[5] The modern exegetes are torn between admiration for the vitality of the character and the disappointment of seeing Elizabeth intentionally suppress her verve[6] and submit, at least outwardly, to male authority.[7] In Susan Fraiman's essay "The Humiliation of Elizabeth Bennett", the author criticises the fact that Elizabeth must forgo her development as a woman in order to ensure the success of "ties among men [such as her father and Darcy] with agendas of their own".[8] The Bennet sisters have only a relatively small dowry of £1,000; and as their family's estate will pass out of their hands when their father dies, the family faces a major social decline, giving the Bennet girls only a limited time in which to find a husband.[9] About feminist criticism of the character, the French critic Roger Martin du Gard wrote that the primary purpose of Austen was to provide jouissance (enjoyment) to her readers, not preach, but the character of Elizabeth is able to manoeuvre within the male-dominated power structure of Regency England to assert her interests in a system that favours her father, Mr Darcy, and the other male characters.[10] Gard noted that the novel hardly glorifies patriarchy since it is strongly implied that it was the financial irresponsibility of Mr Bennet that has placed his family in a precarious social position.[10] Furthermore, it is Elizabeth who criticises her father for not doing more to teach her sisters Lydia and Catherine the value of a good character, which Mr Bennet disregards, leading to Lydia's eloping with Wickham.[11] Unlike the more superficial and/or selfish characters like Lydia, Wickham, Mr Collins, and Charlotte, who regard marriage as a simple matter of satisfying their own desires, for the more mature Elizabeth marriage is the cause of much reflection and serious thought on her part.[12]

The British literacy critic Robert Irvine stated that the reference in the novel to the militia being mobilised and lacking sufficient barracks, requiring them to set up camps in the countryside dates the setting of the novel to the years 1793–1795 as the militia was mobilised in 1793 after France declared war on Great Britain and the last of the barracks for the militia were completed by 1796.[13] Irvine argued that a central concern in Britain in the 1790s, when Austen wrote the first draft of Pride and Prejudice under the title First Impressions was the need for British elites, both national and regional to rally around the flag in face of the challenge from revolutionary France.[14] It is known that Austen was working on First Impressions by 1796 (it is not clear when she began working on the book) and finished off First Impressions in 1797.[15] Irvine states that the character of Elizabeth is clearly middle-class, while Mr Darcy is part of the aristocracy.[16] Irvine wrote "Elizabeth, in the end, is awed by Pemberly, and her story ends with her delighted submission to Darcy in marriage. It is gratitude that forms the foundation of Elizabeth Bennet's love for Fitzwilliam Darcy: caught in a reciprocal gaze with Darcy's portrait at Pemberly, impressed with the evidence of his social power that surrounds her, Elizabeth 'thought of his regard with a deeper sentiment of gratitude than it had ever raised before' ... Elizabeth's desire for Darcy does not happen despite the difference in their social situation: it is produced by that difference, and can be read as a vindication of the hierarchy which constructs that difference in the first place".[17] Irvine observes that Darcy spends about half his time in London while for people in Meryton London is a stylish place that is very far away, observing that a key difference is when one of the Bennet family is ill, they use the services of a local apothecary while Mr Darcy calls upon a surgeon from London.[18] In this regard, Irvine argued that the marriage of Elizabeth and Darcy stands for the union of local and national elites in Britain implicitly against the challenge to the status quo represented by the French Republic.[19]

By contrast, the American scholar Rachel Brownstein argued that Elizabeth rejects two offers of marriage by the time she arrives at Pemberley, and notes in rejecting Mr Collins that the narrator of the novel paraphrases the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft that Elizabeth cannot love him because she is "a rational creature speaking the truth from her heart".[20] Brownstein notes that it is reading Darcy's letter following her first rejection of him that leads her to say "Till this moment, I never knew myself".[21] Brownstein further states that Austen has it both ways in depicting Elizabeth as she uses much irony. After Elizabeth rejects Darcy and then realises she loves him, she comments "no such happy marriage could now teach the admiring multitude what connubial felicity really was" as if she herself is aware that she is a character in a romance novel.[21] Later, she tells Darcy in thanking him for paying off Wickham's debts and ensuring Lydia's marriage that they might be in the wrong, "for what become of the moral, if our comfort springs from a breach of promise, for I ought not to have mentioned the subject?".[21]

Brownstein argues that Austen's ironical way of depicting Elizabeth allows her to present her heroine as both a "proto-feminist" and a "fairy-tale heroine".[21] At one point, Elizabeth says: "I am resolved to act in that manner, which will, in my own opinion, constitute my happiness, without reference to you, or to any other person wholly unconnected with me".[22] The American scholar Claudia Johnson wrote that this was a surprisingly strong statement for a female character in 1813.[22] Likewise, Elizabeth does not defer to the traditional elite, saying of Lady Catherine's opposition to her marrying Darcy: "Neither duty nor honor nor gratitude have any possible claim on me, in the present instance. No principle of either, would be violated by my marriage with Mr Darcy".[23] In the same, Elizabeth defends her love of laughter as somewhat life-improving by saying: "I hope I never ridicule what is wise or good".[23] Elizabeth regards herself as competent to judge what is "wise and good", and refuses to let others dictate to her what she may or may not laugh at, making her one of the most individualistic of Austen heroines.[23] However, Johnson noted that Austen hedged her bets here, reflecting the strict censorship imposed in Britain during the wars with France; Elizabeth reaffirms her wish to be part of the elite by marrying Darcy, instead of challenging it, as she says: "He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman's daughter; so far we are equal."[24] In the same way Austen avoids the issue of filial obedience – questioning of which would have marked her out as a "radical" – by having Mrs Bennet tell her daughter she must marry Collins where her father says she must not.[22] However, the way in which both Elizabeth's parents are portrayed as, if not bad parents, then at least not entirely good parents, implies that Elizabeth is more sensible and able to judge people better than both her mother and father, making her the best one to decide who her husband should be.[22] Reflecting her strong character, Elizabeth complains that Bingley is a "slave of his designing friends", noting for all his pleasantness that he does not have it in him to really stand up for himself; Johnson wrote the "politically potent metaphor" of describing Bingley as a "slave" was a potential reflection of Austen's abolitionist sentiments.[25]

Susan Morgan regards Elizabeth's major flaw to be that she is "morally disengaged" – taking much of her philosophy from her father, Elizabeth observes her neighbours, never becoming morally obligated to make a stand.[26] Elizabeth sees herself as an ironic observer of the world, making fun of those around her.[27] Elizabeth's self-destination is one of scepticism and opposition to the world around her, and much of the novel concerns her struggle to find her own place in a world she rejects.[28] At one point, Elizabeth tells Darcy: "Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies do divert me, I own, and I laught at them whenever I can".[29] Though Elizabeth is portrayed as intelligent, she often misjudges people around her because of her naivety – for example, misunderstanding the social pressures on her friend Charlotte to get married, being taken in completely for a time by Wickham and misjudging Darcy's character.[30] After hearing Wickham's account disparaging Darcy's character, and being advised by her sister Jane not to jump to conclusions, Elizabeth confidently tells her "I beg your pardon – one knows exactly what to think".[31]

However, Elizabeth is able to see, albeit belatedly, that Wickham had misled her about Darcy, admitting she was too influenced by "every charm of air and address".[32] Gary Kelly argued that Austen as the daughter of a Church of England minister would have been very familiar with the Anglican view of life as a "romantic journey" in which God watches over stories of human pride, folly, fall and redemption by free will and the ability to learn from one's mistakes.[33] Kelly argued that aspects of the Anglican understanding of life and the universe can be seen in Elizabeth, who, after rejecting Darcy and then receiving his letter explaining his actions, rethinks her view of him, and comes to understand that her pride and prejudice had blinded her to who he really was, marking the beginning of her romantic journey of "suffering and endurance" that ends happily for her.[34]

After seeing Pemberley, Elizabeth realises Darcy's good character, and sees a chance to become part of society without compromising her values.[35] At Pemberley, Elizabeth sees the "whole scene" from one viewpoint and then sees the "objects were taking different positions" from another viewpoint while remaining beautiful, which is a metaphor for how her subjectivity had influenced her view of the world.[36] Like other Austen heroines, Elizabeth likes to escape into the gardens and nature in general when under pressure.[37] For Austen, gardens were not only places of reflection and relaxation, but also symbols of femininity and of England.[38] The American scholar Alison Sulloway wrote: "Austen had seen and suffered enough causal exploitation so that she took the pastoral world under her tender but unobtrusive fictional protection, just as she felt protective towards human figures under the threat of abuse or neglect".[39] Beyond that, Napoleon had often talked of a desire to make England's fair gardens and fields his own, speaking as if England "...was a mere woman, ripe for his exploitation", so for Austen, the beauty of the English countryside served as a symbol of the England her brothers serving in the Royal Navy were fighting to protect.[37] Elizabeth's connection with nature leads to appreciate the beauty of Pemberley, which allows hers to see the good in Darcy.[40] Notably, Elizabeth is not guided by financial considerations, and refuses to seek favour with the wealthy aristocrat Lady Catherine de Bourgh.[41] Despite Mr Darcy's wealth, Elizabeth turns down his first marriage proposal and only accepts him after she realises that she loves him.[42] Johnson wrote that given the values of Regency England, it was inevitable and expected that a young woman should be married, but Elizabeth makes it clear that what she wants is to marry a man she loves, not just to be married to somebody, which was a quietly subversive message for the time.[43]

In the early 19th century, there was a genre of "conduct books" settling out what were the rules for "propriety" for young women, and the scholar Mary Poovey argued in her 1984 book The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer, which examined the "conduct books", that one of the main messages was that a "proper young lady" never expresses any sexual desire for a man.[44] Poovey argued that in this context, Elizabeth's wit is merely her way of defending herself from the rules of "propriety" set out by the conduct books as opposed to being a subversive force.[44] In this regard, Poovey argued that Austen played it safe by having Elizabeth abandon her wit when she falls in love with Darcy, taking her struggle into effort to mortify Darcy's pride instead of seeking him out because she loves him.[44] The conduct books used a double meaning of the word modesty, which meant both to be outwardly polite in one's conduct and to be ignorant of one's sexuality.[44] This double meaning of modesty placed women in a bind, since any young woman who outwardly conformed to expectations of modesty was not really modest at all, as she was attempting to hide her awareness of sexuality.[44] In the novel, when Elizabeth rejects Mr Collins's marriage proposal, she explains she is being modest in rejecting an offer from a man she cannot love, which leads her to be condemned for not really being modest.[44] Mr Collins often cites one of the more popular "conduct books", Sermons to Young Women, which was published in 1766, but was especially popular in the decades from 1790 to 1810.[45] Unlike the conduct books which declared that women should look back on the past as a way of self-examination, Elizabeth says: "Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure".[46]

Johnson wrote that changes in expectations for women's behavior since Austen's time has led many readers today to miss "Elizabeth's outrageous unconventionality" as she breaks many of the rules for women set out by the "conduct books".[45] Johnson noted that Collins approvingly quotes from Sermons to Young Women that women should never display any "briskness of air and levity of deportment", qualities that contrasted strongly with Elizabeth who has "a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in anything ridiculous".[47] The liveliness of Elizabeth also extends to the physical sphere, as she displays what Johnson called "an unladylike athleticism".[47] Elizabeth walks for miles, and constantly jumps, runs and rambles about, which was not considered conventional behavior for a well-bred lady in Regency England.[47] The narrator says that Elizabeth's temper is "to be happy", and Johnson wrote that her constant joy in life is what "makes her and her novel so distinctive".[48] Johnson wrote: "Elizabeth's relationship with Darcy resonates with a physical passion...The rapport between these two from start to finish is intimate, even racy".[49] Johnson wrote that the way in which Elizabeth and Darcy pursue each other in secret puts their relationship "on the verge of an impropriety unique in Austen's fiction".[49] Many of the remarks made by Elizabeth to Darcy such as "Despise me if you dare" or his "I am not afraid of you" resound with sexual tension, which reflected "Austen's implicit approval of erotic love".[50]

An unconventional character

In her letter to Cassandra dated 29 January 1813, Jane Austen wrote: "I must confess that I think her as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, and how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least I do not know".[51] Austen herself wrote to Cassandra about one fan of her books that "Her liking Darcy & Elizth is enough".[52] The book notes that "Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies" are what delight Elizabeth, which Brownstein noted also applied to Austen as well.[53] This mix of energy and intelligence, and her gaiety and resilience make Elizabeth a true Stendhal heroine according to Tony Tanner, and he adds that there are not many English heroines that we can say that of.[54] Elizabeth Bowen, however, found her charmless, whilst to Edmund Crispin's fictional detective Gervase Fen she and her sisters were "intolerable...those husband-hunting minxes in Pride and Prejudice".[55]

In popular culture

The character of Elizabeth Bennet, marked by intelligence and independent thinking, and her romance with the proud Mr. Darcy have carried over into various theatrical retellings. Rosina Filippi's adapted Pride and Prejudice in a play called The Bennets which was performed at the Royal Court Theatre on 29 March 1901.[56] The play was directed by and featured Harcourt Williams and Winifred Mayo (as Elizabeth Bennet).[57]

Helen Fielding's novel Bridget Jones's Diary, as well as the film series of the same name, is a modern adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, with Elizabeth as Renée Zellweger's title character. In Gurinder Chadha's Bollywood adaptation, Bride and Prejudice, Aishwarya Rai plays the Elizabeth character, Lalita Bakshi. In the 2008 television film Lost in Austen, actress Gemma Arterton plays a version of Lizzy who switches places with a modern-day young woman. Lily James starred as the zombie-slaying Elizabeth Bennet in the film version of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, a popular novel by Seth Grahame-Smith.[58] Fire Island is a modern day retelling of Pride and Prejudice, recasting the Bennett family as a queer found family, with screenwriter Joel Kim Booster starring as the Elizabeth corollary.[59]

One of the most notable portrayals of the character has been that of Jennifer Ehle in the 1995 BBC mini series Pride and Prejudice (1995 TV series) directed by Simon Langton. Ehle won the British Academy Television Award for the Best Actress in 1996. Keira Knightley in Pride & Prejudice, directed by Joe Wright was nominated at the Best Actress Academy Award for her performance.

Depictions in film and television

Film

Television

| Year | Actress | Role | Television programme | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Curigwen Lewis | Elizabeth Bennet | Pride and Prejudice | Television film |

| 1949 | Madge Evans | Elizabeth Bennet | The Philco Television Playhouse | Season 1, episode 17: "Pride and Prejudice" |

| 1952 | Daphne Slater | Elizabeth Bennet | Pride and Prejudice | TV mini-series |

| 1957 | Virna Lisi | Elisabeth Bennet | Orgoglio e pregiudizio | An adaptation in Italian. |

| 1958 | Jane Downs | Elizabeth Bennet | Pride and Prejudice | TV mini-series |

| Kay Hawtrey | Elizabeth Bennet | General Motors Theatre | Episode: "Pride and Prejudice". Originally aired 21 December. | |

| 1961 | Lies Franken | Elizabeth Bennet | De vier dochters Bennet | An adaptation in Dutch. |

| 1967 | Celia Bannerman | Elizabeth Bennet | Pride and Prejudice | 6-episode television series. |

| 1980 | Elizabeth Garvie | Elizabeth Bennet | Pride and Prejudice | 5-episode television series. |

| 1995 | Jennifer Ehle | Elizabeth Bennet | Pride and Prejudice | Six-episode television series. Won – British Academy Television Award for Best Actress |

| Dee Hannigan | Elizabeth Bennet | Wishbone | Season 1, episode 25: "Furst Impressions" | |

| 1997 | Julia Lloyd | Elizabeth Bennet | Red Dwarf | Season 7, episode 6: "Beyond a Joke" |

| 2001 | Lauren Tom | Elizabeth Bennet | Futurama | Season 3, episode 10: "The Day the Earth Stood Stupid" |

| 2008 | Gemma Arterton | Elizabeth Bennet | Lost in Austen | A fantasy adaptation of Pride and Prejudice in which a modern woman trades places with Elizabeth Bennet. |

| 2012–2013 | Ashley Clements | Lizzie Bennet | The Lizzie Bennet Diaries | Web series. A modern adaptation in which the story of Pride and Prejudice is told through vlogs. |

| 2013 | Anna Maxwell Martin | Elizabeth Darcy/Mrs Darcy | Death Comes to Pemberley | Three-part series based on P. D. James's novel about events after Pride and Prejudice. |

| 2018 | Nathalia Dill | Elisabeta Benedito | Orgulho e Paixão | A Brazilian telenovela based on Jane Austen's works. |

References

- ^ William Dean Howells 2009, p. 48

- ^ "Pride and Prejudice: Elizabeth Bennet". sparknotes.com.

- ^ Wright, Andrew H. "Elizabeth Bennet." Elizabeth Bennet (introduction by Harold Bloom). Broomall: Chelsea House Publishers , 2004. 37–38. Google Book Search. Web. 22 October 2011.

- ^ Pride and Prejudice. Chapter 29.

- ^ In a letter to Sir William Elford dated 20 December 1814.

- ^ Morrison, Robert, ed. (2005). Jane Austen's Pride and prejudice : a sourcebook. New York, NY [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 9780415268493.

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007 , p. 201.

- ^ Fraiman, Susan (1993). Unbecoming Women: British Women Writers and the Novel of Development. Columbia University Press. p. 73.

- ^ MacDonagh, Oliver "Minor Female Characters Depict Women's Roles", pp. 85-93 (88), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ a b Gard, Roger "Questioning the Merit of Pride and Prejudice", pp. 111–117, in Readings on Pride and Prejudice ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ MacDonagh, Oliver "Minor Female Characters Depict Women's Roles", pp. 85–93 (89), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Brown, Julia Prewit "The Narrator's Voice" from Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999, pp. 103–110 (109).

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 58.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, pp. 57, 59.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Brownstein, Rachel "Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice", pp. 32–57 (53), in The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ a b c d Brownstein, Rachel "Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice", pp. 32-57 (54), in The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 87.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, pp. 88.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Morgan, Susan (August 1975). "Intelligence in "Pride and Prejudice"". Modern Philology. 73 (1): 54–68. doi:10.1086/390617. JSTOR 436104. S2CID 162238146.

- ^ Murdick, Marvin "Irony as a Tool for Judging People", pp. 136–143 (136–37), Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 102.

- ^ Murdick, Marvin "Irony as a Tool for Judging People", pp. 136–43 (136), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Murdick, Marvin "Irony as a Tool for Judging People" pp. 136-43 (142), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Tave, Stuart (1999). "Elizabeth and Darcy's Mutual Mortification and Renewal". In Swisher, Clarice (ed.). Readings on Pride and Prejudice. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. p. 71. ISBN 9781565108608.

- ^ Duckworth, Alistair (1999). "Social moderation and the middle wary". In Swisher, Clarice (ed.). Readings on Pride and Prejudice. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. p. 46. ISBN 9781565108608.

- ^ Kelly, Gary "Religion and Politics", pp. 149-169 (165), in The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, ed. Edward Copeland and Juliet McMaster, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ Kelly, Gary "Religion and Politics", pp. 149–169 (166), in The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, in Edward Copeland and Juliet McMaster, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ Duckworth, Alistair "Social moderation and the middle wary", pp. 42-51 (46–47), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Duckworth, Alistair "Social moderation and the middle wary", pp. 42–51 (48–49) in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ a b Sulloway, Alison "The Significance of Gardens and Pastoral Scenes", pp. 119–127 (120–21), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Sulloway, Alison "The Significance of Gardens and Pastoral Scenes", pp. 119–127 (119–20), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Sulloway, Alison "The Significance of Gardens and Pastoral Scenes", pp. 119-127 (120), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice ed. by Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Sulloway, Alison "The Significance of Gardens and Pastoral Scenes", pp. 119–127 (125), in Readings on Pride and Prejudice, ed. Clarice Swisher, San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999.

- ^ Ross, Josephine Jane Austen A Companion, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002, p. 200.

- ^ Ross, Josephine Jane Austen A Companion, London: John Murray, 2002, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, pp. 89-90.

- ^ a b c d e f Irvine, Robert Jane Austen, London: Routledge, 2005, pp. 126.

- ^ a b Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 75.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 77.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 74.

- ^ a b Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 90.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia Jane Austen, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, pp. 90–91.

- ^ "Jane Austen -- Letters -- Other excerpts from letters in Austen-Leigh's "Memoir"". pemberley.com.

- ^ Brownstein, Rachel M. (1997). "Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice". The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780521498678.

- ^ Brownstein, Rachel "Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice", pp. 32–57 (55), in The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ Tanner, Tony (1986). Jane Austen. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University press. p. 105. ISBN 9780674471740.

- ^ Quoted in R. Jenkyns, A Fine Brush on Ivory (Oxford 2007), p. 85

- ^ Looser, Devoney (2017). The Making of Jane Austen. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1421422824.

- ^ The Croydon Guardian (6th April 1901)

- ^ Dave McNary (4 August 2014). "'Pride and Prejudice and Zombies' Casts Lily James, Sam Riley, Bella Heathcote". Variety.

- ^ Martinelli, Marissa (7 June 2022). "Fire Island Is a Surprisingly Faithful Jane Austen Adaptation (Albeit With More Poppers)". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

Bibliography

- Austen, Jane (1907). Pride and Prejudice. Dent.

- Howells, William Dean (1901). Heroines of Fiction, Volume 1. Harper and Brothers. pp. 37–48.

- Nardin, Jane (1973). Those Elegant Decorums: The Concept of Propriety in Jane Austen's Novels. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-236-7.