Eremotherium

| Eremotherium Temporal range: Early Pliocene-Early Holocene (Blancan-Rancholabrean (NALMA) & Montehermosan-Lujanian (SALMA)

~ | |

|---|---|

| |

| E. laurillardi at the HMNS | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Clade: | †Megatheria |

| Family: | †Megatheriidae |

| Subfamily: | †Megatheriinae |

| Genus: | †Eremotherium Spillmann, 1948 |

| Type species | |

| †Megatherium laurillardi Lund, 1842

| |

| Other species | |

| |

| |

| Range of Eremotherium | |

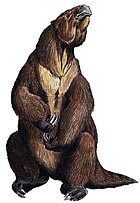

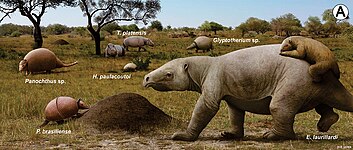

Eremotherium (from Greek for "steppe" or "desert beast": ἔρημος "steppe or desert" and θηρίον "beast") is an extinct genus of giant ground sloth in the family Megatheriidae. Eremotherium lived in southern North America, Central America, and northern South America from the Pliocene, around 5.3 million years ago, to the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 10,000 years ago. Eremotherium was one of the largest ground sloths, with a body size comparable to elephants, weighing around 4–6.5 tonnes (4.4–7.2 short tons) and measuring about 6 metres (20 ft) long, slightly larger than its close relative Megatherium.

Eremotherium was widespread in tropical and subtropical lowlands and lived there in partly open and closed landscapes, while its close relative Megatherium lived in more temperate climes of South America. Characteristic of Eremotherium was its robust physique with comparatively long limbs and front and hind feet especially for later representatives- three fingers. However, the skull is relatively gracile, the teeth are uniform and high-crowned. Like today's sloths, Eremotherium was purely herbivorous and was probably a mixed feeder that dined on leaves and grasses that adapted its diet to local environments and climates. Like Megatherium, Eremotherium is suggested to have been capable of adopting a bipedal posture to feed on high-growing leaves.

Finds of Eremotherium are common and widespread, with fossils being found as far north as South Carolina in the United States and as far south as Rio Grande Do Sul in Brazil, and many complete skeletons have been unearthed.

Only two valid species are known, Eremotherium laurillardi and E. eomigrans, the former was named by prolific Danish paleontologist Peter Lund in 1842 based on a tooth of a juvenile individual that had been collected from Pleistocene deposits in caves in Lagoa Santa, Brazil alongside fossils of thousands of other megafauna. Lund originally named it as a species of its relative Megatherium, though Austrian paleontologist Franz Spillman later created the genus name Eremotherium after noticing its distinctness from other megatheriids.

History and naming

The taxonomic history of Eremotherium largely involves it being confused with Megatherium and the naming of many additional species that are actually synonymous with E. laurillardi. For many years fossils from the genus have been known, with records from as early as 1823 when fossil collectors J. P. Scriven and Joseph C. Habersham collected several teeth, skull, and mandible fragments, including a nearly complete set of mandibles, from Quaternary age deposits in Skidaway Island, Georgia in the United States.[1][2][3] The fossils were not described until 1852 however, when American paleontologist named Megatherium mirabile, based on the specimens (specimen numbers USNM 825-832 + 837) but the species has since been synonymized with Eremotherium laurillardi.[1] The first published discovery was only a year after M. mirabile was discovered, when portions of 2 teeth that had been also collected from Skidaway Island were referred to Megatherium later in 1823 by Dr. Samuel L. Mitchell.[4] 20 more fossils from the island were reported in 1824 by naturalist William Cooper, including mandibular, limb, and dental remains, that now reside at the Lyceum of Natural History in New York, that had also been collected by Joseph C. Habersham.[4][5]

Several other discoveries from Georgia and South Carolina were described as Megatherium throughout the 1840s and 1850s, like in 1846 when Savannah scholar William B. Hodgson described some "Megatherium" fossils from Georgia that had been donated by Habersham, including portions of several skulls, in a collection that included fossils of several other Pleistocene megafauna like mammoths and bison.[2][4] These were all described in more detail by Joseph Leidy in 1855, but they were not all referred to Eremotherium until the late 20th century.[2] In 1842, Richard Harlan named a new species of the turtle Chelonia, Chelonia couperi, based on a supposed femur, or thigh bone, that had been found in the Brunswick Canal in Glynn County, Georgia and dated to the Pleistocene.[6] It was not until 1977 that further analysis demonstrated that the "femur" was actually a clavicle from Eremotherium.[7] It is unknown, which publication was published first - according to the regulations of the ICZN, the species name of the first publication would have priority, even if it was attached to another genus - but the species name E. couperi is rarely used, while E. laurillardi is more widely used and has been adopted by more scientists.[1]

Fossils from South America were first described by Danish paleontologist and founder of Brazilian paleontology Peter Wilhelm Lund when he established a new species of Megatherium based on two teeth (specimen number ZMUC 1130 and 1131) from Lapa Vermella, a cave in the valley of the Rio de la Velhas in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais under the name Megatherium laurillardi, the first named species now assigned to Eremotherium.[8] Lund diagnosed the species based on the size of the teeth, which were only a quarter the size of Megatherium americanum, the greatest representative of Megatherium, and he believed that it was a tapir-sized animal.[8] Today, the teeth are considered to be from a juvenile of E. laurillardi and adults reached or exceeded the size of M. americanum.[9] Two years earlier, Lund had already figured teeth found at Lapa Vermella, which he assigned to Megatherium americanum due to their dimensions, which he figured alongside those of M. laurillardi in the 1842 publication.[10][8] They also have been referred to Eremotherium laurillardi. For many years, E. laurillardi's holotype was speculated to actually have come from a dwarf species of Eremotherium while the larger fossils belonged to another distinct species like E. rusconii, a species that was erected by Samuel Schaub in 1935 for giant fossils from Venezuela, though it was initially thought to be a species of Megatherium.[11][12] However, this view is mostly contradicted and argues that at least in the Late Pleistocene in South and North America there was only a single species, E. laurillardi, which had a strong sexual dimorphism.[12] Discoveries of extensive material of Eremotherium at sites such as those at Nova Friburgo in Brazil and Daytona Beach in Florida further prove that the two were synonymous and lacked any major differences between populations.[12]

Fossils of Eremotherium from Mexico were first described in 1882 by French scientist Alfred Duges, though they consisted only of a fragmentary left femur, as a new species of the South American Scelidotherium, naming it S. guanajatense.[13] The femur had been found in Pleistocene deposits in Guanajuato, Mexico, but the fossil has since been lost and the species is a synonym of E. laurillardi.[14] Another species that is currently considered valid was described in 1997 by Canadian zoologist Gerardo De Iuliis and French paleontologist Pierre-Antoine St-Andréc based on a single, approximately 39 cm long femur from the Pleistocene strata in Ulloma, Bolivia as Eremotherium sefvei, though it was first described in 1915 as a fossil of Megatherium.[15][16] E. sefvei's geologic aging is less definite can only be placed in the general Pleistocene, but it is the smallest representative of Eremotherium and all post-Miocene megatheriids.[17][10]

Two years later in 1999, De Iuliis and Brazilian paleontologist Carlos Cartelle erected another species of Eremotherium now seen as valid, E. eomigrans, based on a partial skeleton, the holotype, that had been unearthed from the latest Blancan (Latest Pliocene) layers of Newberry, Florida, USA, though many other fossils from the area were referred to it.[18] Many of the fossils were isolated and had been recovered from sinkholes, river canals, shorelines, and hot springs, with few of the specimens being associated skeletons.[18] So far, the latter has only been found in North America and reached a size similar to E. laurillardi, but comes from the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene and bares a pentadactyl, or five fingered, hand in contrast to the tridactyl hands of Megatherium and E. laurillardi.[18]

The genus name Eremotherium was not erected until 1948 by Franz Spillmann, erecting a new species, E. carolinese, as the type species of the genus based on a 65 cm long skull with associated lower jaw, both fossils come from the Santa Elena Peninsula in Ecuador, and the species name was after the local village of Carolina.[19] Although it was the type species of the genus for many years, the species has since been synonymized with E. laurillardi and has been replaced by it as the type species. The generic name Eremotherium is derived from the Greek words ἔρημος (Erēmos "Steppe", "desert") and θηρίον (Thērion "animal") after the landscape in Santa Elena Peninsula that E. carolinese was unearthed from.[19] The following year, French taxonomist Robert Hoffstetter introduced the genus Schaubia for Samuel Schaub's Megatherium rusconii because he recognized its generic distinctness from Megatherium,[20] though the genus name was preoccupied, so it was renamed Schaubtherium the following year.[21] It was not until 1952 that he recognized similarities to Spillmann's Eremotherium and synonymized the two.[22] Another dubious genus and species, Xenocnus cearensis, was dubbed in 1980 by Carlos de Paula Couto based on a partial unciform (wrist bone), though he mistook as the astragalus (tarsal bone) of a megalochynid, that had been found in Pleistocene deposits in Itapipoca, Brazil.[23][24] Paula Couto even created a new subfamily, Xenocninae, for the genus,[23] but reanalysis in 2008 proved that the fossil was instead from Eremotherium laurillardi.[24]

Description

Size

Eremotherium was slightly larger than the closely related Megatherium in size, reaching an overall length of 6 metres (20 ft) and a height of 2 metres (6.6 ft) while on all fours, possibly up to 4 metres (13 ft) when it reared up on its hind legs,[25] and weighing around 3,960–6,550 kilograms (8,730–14,440 lb).[26][27][28] In any case, it is one of the largest land-dwelling mammals of that time in the Americas, along with the proboscideans that migrated from Eurasia.[29][30] As a ground-dwelling sloth, it had relatively shorter and stronger limbs compared to modern arboreal sloths and also had a longer tail.[31]

Skull

The skull of Eremotherium was large and massive, but lighter in build compared to Megatherium. A complete skull measured 65 cm in length and was up to 33 cm wide at the zygomatic arches; at its highest, it reached 19 cm in height. The forehead line was clearly straight and not as wavy as in Megatherium. The nasal bone was shortened compared to the skull of Megatherium, giving it an overall truncated cone appearance. Further differences to Megatherium existed at the premaxillary bone: In Eremotherium this had an overall triangular shape and was only loosely connected to the upper jaw, whereas in Megatherium the premaxillary bone had a quadrangular shape, as well as a firm connection to the upper jaw.[1] The occipital bone is semicircular in posterior view and sloped backwards in lateral view. The articular surfaces as the point of attachment of the cervical spine curved far outwards and were relatively larger than in tree sloths and numerous other ground sloths. The parietal bones had a far outward curved shape, which was partly caused by the large cranial cavity with a volume of 1600 cm³. The strong zygomatic arch was closed, unlike today's sloths, but like the latter it had a massive bony outgrowth pointing downwards and backwards from the anterior base of the arch. In addition, a third outgrowth protruded diagonally upwards. The downward pointing bony process was clearly steeper than in other sloths. The eye socket was shallow and small and slightly lower than in Megatherium or modern sloths.[32][33][34][35]

The lower jaw was about 55 centimetres (22 in) long, both halves were connected by a strong symphysis, which extended forward in a spatulate shape and ended in a rounded shape. Typical for all representatives of the Megatheriidae was the clearly downward curved course of the lower edge of the bone body, which resulted from the different length of the teeth. In Eremotherium this caused the lower jaw to be 14.5 centimetres (5.7 in) deep below the symphysis, 15 cm below the second tooth and 12.5 cm below the fourth. The thickness of the curvature of the lower margin of the mandible increased significantly in the course of individual development, but the ratio of the height of the mandibular body to the length of the tooth row remained largely the same. This differs markedly from Megatherium, in which the height of the mandible increased not only in absolute terms, but also relatively in relation to the length of the dentition.[36] The mandibular body was also very thick, leaving little space for the tongue. The crown process rose up to 27 centimetres (11 in), and the articular process was only slightly lower. At the posterior, lower end there was a strong, clearly notched angular process, the upper edge of which was approximately at the level of the masticatory plane. At the anterior edge of the lower jaw there was a strong mental foramen. The dentition was typical for sloths, but in contrast to today's representatives it consisted of completely homodont teeth, which is a characteristic feature of megatherians. Each branch of the jaw had 5 teeth in the upper jaw and 4 in the lower jaw, so in total Eremotherium had 18 teeth. They resembled molars and, except for the front one, were quadrangular in shape, usually a good 5 centimetres (2.0 in) long in large individuals and very high-crowned (hypsodont) with a height of 15 centimetres (5.9 in). They had no roots and grew throughout their entire life. The enamel was also missing. However, two transverse, sharp-edged ridges were typically formed on the chewing surface to help grind food. The entire upper row of teeth grew up to 22 centimetres (8.7 in) long, while the lower reached up to 21 centimetres (8.3 in).[32][37][38][35]

Postcrania

Almost all of the poscranial skeleton is known. The vertebrae were massively shaped, both at the vertebral bodies and at the lateral transverse processes. However, the vertebral bodies were compressed in length, so that the tail appeared rather short overall and generally did not exceed the length of the lower limb sections.[39] It had 7 neck vertebrae. The humerus represented a long tube with a bulky lower joint end. The total length was about 79 centimetres (31 in). Distinctive, ridge-like muscle attachments on the middle shaft were typical. The forearm bones had much shorter lengths, with the spoke measuring about 67 cm, and the ulna 57 centimetres (22 in) in length.[40][34] Massive was the femur, which had the broad build characteristic of megatherians and was narrowed in front and behind. It had an average length of 74 cm, the largest bone found so far was 89.5 centimetres (35.2 in) long and 45.1 centimetres (17.8 in) wide. The third trochanter, a prominent muscle attachment point on the shaft, typical of xenarthrans, was absent in Eremotherium as in all other megatherians. The shinbone and fibula were only fused together at the upper end and not also at the lower end as in Megatherium. In this case, the tibia became about 60 cm long.[39][34][41] The forelegs ended in hands with three fingers (III to V). The two inner phalanges (I and II) were fused together with some elements of the carpus, such as the trapezium, to form a unit, the metacarpal-carpal complex (MCC).[42] Thus, Eremotherium clearly deviates from Megatherium and other closely related forms, which possessed four-fingered hands. In Eremotherium, the metacarpal of the third digit was the shortest, measuring 19 cm in length, while those of the fourth and fifth were almost the same length, 28 centimetres (11 in) and 27.5 centimetres (10.8 in) respectively. The phalanx (the third phalanx) of the third and fourth fingers had a long and pointedly curved shape, which suggests correspondingly long claws. The fifth finger had only two phalanges and consequently no claw was formed there. (An exception is the older form E. eomigrans, whose hands, in contrast to other megateria, were still five-fingered, with claws on digits I to IV.)[34][43] The foot, as in all megatheriids, was also three-fingered (digits III to V). It resembled the hand with an extremely short metatarsal of the third finger. That of the fourth finger reached 24 centimetres (9.4 in), that of the fifth 21 centimetres (8.3 in) in length.[39] Deviating from the hand, only the middle digit (III) had three phalanges with a terminal phalanx bearing a long claw. The two outer digit had only two phalanges. This structure of the foot is typical for evolved megatherians.[44][45]

Fossil distribution

Fossils of Eremotherium have been found at over 130 sites.[46] The earliest species, Eremotherium eomigrans is exclusively known from Florida, dating to the late Pliocene. Eremotherium sefvei is only known from a single femur found in Bolivia of an uncertain age, while Eremotherium laurillardi is known from numerous fossils spanning from the late Pliocene to the end of the Pleistocene.[35] The range distribution of Eremotherium laurillardi is the widest of any ground sloth, spanning from 30.5° S to 40.3°N. The northernmost record of the species is in New Jersey, which likely represents a northward extension of its range during a warm interglacial period (probably the Last Interglacial/Sangamonian), while the southernmost record of the genus is in Rio Grande do Sul in southernmost Brazil. Most records of Eremotherium in Brazil are from the Brazilian Intertropical Region (BIR) in the east of the country,[47] and are particularly frequently found in tank deposits (infillings of small depressions caused by erosion).[48] Other records of the genus in North America north of Mexico are confined to the Gulf Coast and Southern Atlantic Coast, including Texas, Florida, South Carolina and Georgia.[49] By the end of the Late Pleistocene Eremotherium was probably absent from North America north of Mexico, though it maintained a wide distribution from Mexico to Brazil at the time of its extinction.[47] Most records of the genus in Mexico are from the southern and midlatitudes.[50] Fossils of Eremotherium have been found at a wide range of altitudes, ranging from sea level to over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft).[50]

Palaeobiology

Locomotion

The predominantly quadrupedal locomotion took place on inwardly turned feet, with the entire weight resting on the outer, fifth and possibly fourth phalanges (a pedolateral gait), whereby the talus was subject to massive reshaping.[51][52] Likewise, the hands were turned inwards, in a position somewhat resembling the forefeet of the similarly clawed Chalicotheriidae, a now extinct group of odd-toed ungulates.[43] It also suggests that locomotion was rather slow. It was also unable to perform digging activities, as has been demonstrated for other large ground sloths, which can also be seen in the construction of the forearm, just as the manipulation of objects was minimised due to the limited ability of the fingers to move in relation to each other. However, Eremotherium was able to stand up on its hind legs and pull branches and twigs with its hands, for example to reach the foliage of tall trees for feeding,[39][53] as well as make defensive strikes with its long claws.[43] The standing up was supported by the strong tail, similar to what is still the case today with armadillos and anteaters. The massive tail vertebrae in the front area of the tail suggest a strong musculature. Among other things, this concerns the coccygeus muscle, which attaches to the ischium and fixes the tail. Less well developed, on the other hand, were the epaxial muscles, which could cause the tail to straighten up.[39]

Social behaviour

Due to some group finds of several individuals at individual sites, such as in El Bajión in Chiapas in Mexico with four animals or in Tanque Loma on the Santa Elena in Ecuador with 22 individuals, some scientists discuss whether Eremotherium possibly lived and roamed in small, herd-like groups.[46][54] Especially in Tanque Loma, the individuals recorded are composed of at least 15 adults and six juveniles. They were all found in close association in a single horizon, and they are interpreted as being contemporary with each other. The possible group was thought to have gathered at a waterhole and died there relatively abruptly due to an unknown event.[54] On the other hand, sometimes clustered occurrences of Eremotherium such as the 19 individuals from the sinkhole of Jirau in Brazil are considered to be accumulations over a long period of time.[55] In the case of the likewise giant ground sloth Lestodon from central South America, experts also interpret mass accumulations of remains of different individuals in part as evidence of phased group formation.[56] Living tree sloths live solitary lives.[57]

Diet

Eremotherium possessed extremely high-crowned teeth, which, however, did not reach the dimensions of those of Megatherium. As the teeth lack enamel, this hypsodonty may not be an expression of specialisation on grass as food, unlike mammals with enamel in their teeth. The different expression of high-crownedness in the two large ground sloths is probably rather to be sought in adaptation to divergent habitats—more tropical lowlands in Eremotherium and more temperate regions in Megatherium.[38] From an anatomical point of view, the only moderately wide snout and the large total chewing surface of the teeth advocate a diet adapted to mixed plant foods. The average surface area of all teeth available for chewing food is 11,340 mm², which roughly corresponds to the values of the closely related Megatherium, but clearly exceeds those of the Lestodon, which is also giant but has a much broader snout. The latter genus belongs to the more distantly related Mylodontidae and was probably a specialised grazer. Moreover, the total purchase area is within the range of variation of present-day elephants, some of which also prefer mixed plant diets.[58][59] Support for this view comes from various isotopic analysis on the teeth of Eremotherium. Thus, the animals probably fed on grass in rather open landscapes, but on foliage in largely closed forests.[60][27] Carbon isotopes and stereo microwear analysis suggest that an individual from the Late Pleistocene (34,705-33,947 cal yr BP), of Goiás, Brazil, was a mixed feeder, suggesting a high proportion of shrubs and trees, this is in contrast to the presumed diet from specimens from Northeast Brazil, which had a diet of C4 herbaceous plants.[61] A 2020 discovery in Ecuador found 22 individuals ranging in age from juveniles to adults preserved together in anoxic marsh sediments, suggesting that Eremotherium may have been gregarious.[62]

Palaeopathologies

Numerous palaeopathologies have been described from E. laurillardi fossils in the BIR. These documented ailments include osteoarthritis and articular depressions, with spondyloarthropathy and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease potentially present as well. These diseases are evidenced by the presence of osteophytes, bone overgrowth, bone erosion, and rough subchondral bone in various specimens.[63] E. laurillardi is also the only xenarthran species from which linear defect is known.[64]

Classification

Eremotherium is a genus of the extinct ground sloth family Megatheriidae, which includes large to very large sloths in the group Folivora, which, together with the Megalonychidae and the Nothrotheriidae, form the superfamily Megatherioidea.[65][66] The Megatherioidea also includes the three-toed sloths of the genus Bradypus, one of the two sloth genera still alive today.[67][68] Eremotherium's closest relative in Megatheriidae is the namesake of the family Megatherium, which was endemic to South America, slightly larger, and preferred more open habitats than Eremotherium. Pyramiodontherium and Anisodontherium are also part of this subfamily, but are smaller and older, dating to the Late Miocene of Argentina. All of these genera belong to the subfamily Megatheriinae, which includes the largest and most derived sloths. The direct phylogenetic ancestor of Eremotherium is unknown, but may be linked to Proeremotherium from the Codore Formation in Venezuela, which dates to the Pliocene. The genus has numerous characteristics that are akin to those of Eremotherium, but are more primitive.[17] Little is known about the evolution of the genus Eremotherium. It may have evolved in the Early Pliocene in South America, where only a few sites from this period are known, and dispersed by crossing the Isthmus of Panama, i.e. the formation of the land bridge connecting North and South America, in the course of the Great American Biotic Interchange. The oldest fossils come from the Pliocene of the southern United States in North America, suggesting that the species instead evolved there before colonizing South America.[69] The discovery of Proeremotherium also supports this hypothesis, indicating that these or other close ancestors of Eremotherium first migrated to North America and evolved there, then moved back southward to South America after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, similar to the glyptodont Glyptotherium.[17]

The following phylogenetic analysis of Megatheriinae within Megatheriidae was conducted by Brandoni et al., 2018[70] that was modified from Varela et al. 2019 based on lower molariform and astragalus morphology:[71]

Relationship with humans and extinction

The disappearance of Eremotherium coincides with the Quaternary Extinction Event, which saw the arrival of humans in the Americas and the extinction of many megafauna, large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant that were larger than or a comparable size to humans, such as mammoths, glyptodonts, and other ground sloths. One of the latest finds of Eremotherium is from Ittaituba on Rio Tapajós, a tributary of the Amazon, that has an uncalibrated C14 date to 11,340 BP (13,470 – 13,140 calibrated) and includes several skull and lower jaw fragments.[72] In a similar period, the finds at Barcelona in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Norte come from strata dating from 11,324 to 11,807 years ago.[citation needed] There is no direct evidence of hunting by humans of Eremotherium. A possible indication of interaction is a tooth of Eremotherium that some authors have suggested had been modified by Paleoindians, which was unearthed from a doline on the site of the São-José farm in the Brazilian state of Sergipe.[73] However, other authors have regarded the idea as poorly evidenced, and the modification was more likely the result of natural processes.[74]

References

- ^ a b c d Cástor Cartelle and Gerardo De Iuliis: Eremotherium laurillardi: The Panamerican Late Pleistocene megatheriid sloth. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(4), 1995, pp. 830–841 ( online )

- ^ a b c Leidy, Joseph (1855). A Memoir on the Extinct Sloth Tribe of North America. Smithsonian Institution.[page needed]

- ^ "Paleobiology Collections Search". collections.nmnh.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ^ a b c Hodgson, W. B., & Habersham, J. C. (1846). Memoir on the Megatherium, and Other Extinct Gigantic Quadrupeds of the Coast of Georgia: With Observations on Its Geologic Feature (Vol. 10). Barlett & Welford.

- ^ Cooper, W. (1824). On the Remains of the Megatherium recently discovered in Georgia. Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York, 1, 114-124.

- ^ Harlan, Richard (October 1842). "Notice of two New Fossil Mammals from Brunswick Canal, Georgia". American Journal of Science and Arts. 43 (1): 141–144. ProQuest 89593263.

- ^ Gillette, David D. (1977). "Catalogue of Type Specimens of Fossil Vertebrates, Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia Part VI: Index, Additions, and Corrections". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 129: 203–211. JSTOR 4064747.

- ^ a b c Lund, P.W., 1842. Blik paa Brasiliens Dyreverden för Sidste Jordomvaeltning. Tredie Afhandling: Forsaettelse af Pattedyrene. Det Kongel. Danske Vidensk. Selsk. Skr. Naturvidensk. Math. Afd. 9, 137–208.

- ^ Cartelle, Cástor; De Iuliis, Gerardo (January 2006). "Eremotherium Laurillardi (Lund) (Xenarthra, Megatheriidae), the Panamerican giant ground sloth: Taxonomic aspects of the ontogeny of skull and dentition". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 199–209. Bibcode:2006JSPal...4..199C. doi:10.1017/S1477201905001781. S2CID 85763823.

- ^ a b Lund, P. W. (1840). Nouvelles recherches sur la faune fossile du Brésil. In Annales des Sciences Naturelles (Vol. 13, pp. 310-319).

- ^ Schaub, S. (1935). Saugetierfunde aus Venezuela und Trinidad, Band 55. Kommissionsverlag von E.

- ^ a b c Cartelle, Cástor; De Iuliis, Gerardo; Pujos, François (January 2015). "Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund, 1842) (Xenarthra, Megatheriinae) is the only valid megatheriine sloth species in the Pleistocene of intertropical Brazil: A response to Faure et al., 2014". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 14 (1): 15–23. Bibcode:2015CRPal..14...15C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2014.09.002. hdl:11336/32035.

- ^ Dugès, A. (1882). Nota sobre un fósil de Arperos. Estado de Guanajuato: El Minero Mexicano, 9(20), 233-235.

- ^ Mones, A. (1973). Note acerca de Eremotherium guanajuatense (Duges, 1882)(Edentata, Megatherioidea) de Araperos, estado de Guanajuato, México.

- ^ De Iuliis, Gerardo; St-André, Pierre-Antoine (January 1997). "Eremotherium sefvei nov. sp. (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Megatheriidae) from the pleistocene of ulloma, Bolivia". Geobios. 30 (3): 453–461. Bibcode:1997Geobi..30..453D. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(97)80210-0.

- ^ Sefve, I. (1915). "Scelidotherium-Reste aus Ulloma". Bolivien: Bulletin of the Geological Institutions of the University of Uppsala. 13: 61–92.

- ^ a b c Carlini, Alfredo A.; Brandoni, Diego; Sánchez, Rodolfo (January 2006). "First Megatheriines (Xenarthra, Phyllophaga, Megatheriidae) from the Urumaco (Late Miocene) and Codore (Pliocene) Formations, Estado Falcón, Venezuela". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (3): 269–278. Bibcode:2006JSPal...4..269C. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001878. hdl:11336/80745. S2CID 129207595.

- ^ a b c Iuliis, Gerardo; Cartelle, Castor (December 1999). "A new giant megatheriine ground sloth (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the late Blancan to early Irvingtonian of Florida". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 127 (4): 495–515. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1999.tb01383.x. S2CID 84951254.

- ^ a b Spillmann, F. (1948). Beitrge zur Kenntnis eines neuen gravigraden Riesensteppentieres (Eremotherium carolinenese gen. et. spec. nov.), seines Lebensraumes und seiner Lebensweise. Palaeobiologica, 8(3), 231-279.

- ^ Hoffstetter, R. (1949). Sobre los Megatheriidae del Pleistoceno del Ecuador, Schaubia, gen. nov. Boletín de Informaciones Científicas Nacionales, 3(25).

- ^ Hoffstetter, Robert (1950). "Rectification de nomenclature: Schaubitherium, nom. nov. pour Schaubia Hoffst. 1949". Compte Rendu Sommaire des Séances de la Société Géologique de France. 1950: 234–235.

- ^ Hoffstetter, R. (1952). Les mammifères Pléistocènes de la République de l'Equateur. Soc.

- ^ a b Couto, C. de Paula (1980). "Fossil pleistocene to sub-recent mammals from northeastern Brazil. I - Edentata megalonychidae". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 52 (1): 143–151. INIST PASCALGEODEBRGM8020478183.

- ^ a b Cartelle, Cástor; De Iuliis, Gerardo; Pujos, François (August 2008). "A new species of Megalonychidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Quaternary of Poço Azul (Bahia, Brazil)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 7 (6): 335–346. Bibcode:2008CRPal...7..335C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2008.05.006.

- ^ Cartelle, Cástor (2000). "Preguiças terrícolas, essas desconhecidas". Ciência Hoje (in Portuguese). Instituto Ciência Hoje.

- ^ McDonald, H. Gregory (2023-06-06). "A Tale of Two Continents (and a Few Islands): Ecology and Distribution of Late Pleistocene Sloths". Land. 12 (6): 1192. doi:10.3390/land12061192. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ^ a b Dantas, Mário André Trindade; Cherkinsky, Alexander; Bocherens, Hervé; Drefahl, Morgana; Bernardes, Camila; França, Lucas de Melo (15 August 2017). "Isotopic paleoecology of the Pleistocene megamammals from the Brazilian Intertropical Region: Feeding ecology (δ13C), niche breadth and overlap". Quaternary Science Reviews. 170: 152–163. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.06.030. ISSN 0277-3791. Retrieved 2 January 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (1998). "Terramegathermy And Cope's Rule In The Land Of Titans" (PDF). In Wimbledon, W.A; Fraser, N (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. pp. 179–217. ISBN 90-5699-183-3. S2CID 209844769.

- ^ Richard M. Fariña, Sergio F. Vizcaíno and Gerardo de Iuliis: Megafauna. Giant beasts of Pleistocene South America. Indiana University Press, 2013, pp. 1-436 (pp. 216-218) ISBN 978-0-253-00230-3

- ^ Sergio F. Vizcaíno, M. Susasna Bargo and Richard A. Fariña: Form, function, and paleobiology in xenarthrans. In: Sergio F. Vizcaíno and WJ Loughry (eds.): The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida, 2008, pp. 86-99

- ^ M Susana Bargo, Sergio F Vizcaíno, Fernando M Archuby and R Ernesto Blanco: Limb bone proportions, strength and digging in some Lujanian (Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene) mylodontid ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(3), 2000, pp. 601-610

- ^ a b Franz Spillmann: Contributions to the knowledge of a new gravigrade giant steppe animal (Eremotherium carolinense gen. et sp. nov.), its habitat and its way of life. Palaeobiologica 8, 1948, pp. 231-279

- ^ Cástor Cartelle and Gerardo De Iuliis: Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund) (Xenarthra, Megatheriidae), the Panamerican giant ground sloth: Taxonomic aspects of the ontogeny of skull and dentition. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4 (2), 2006, pp. 199-209

- ^ a b c d Gerardo De Iuliis and Cástor Cartelle: A new giant megatheriine ground sloth (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the late Blancan to early Irvingtonian of Florida. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 127, 1999, pp. 495-515

- ^ a b c Virginia L Naples and Robert K McAfee: Reconstruction of the cranial musculature and masticatory function of the Pleistocene panamerican ground sloth Eremotherium laurillardi (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Megatheriidae). Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology 24 (2), 2012, pp. 187-206

- ^ Cástor Cartelle, Gerardo De Iuliis and François Pujos: Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund, 1842) (Xenarthra, Megatheriinae) is the only valid megatheriine sloth species in the Pleistocene of intertropical Brazil: A response to Faure et al., 2014. Comptes Rendus Palevol 14, 2014, pp. 15-23

- ^ Martine Faure, Claude Guérin and Fabio Parenti: Sur l'existence de deux specèces d'Eremotherium E. rusconii (Schaub, 1935) et E. laurillardi (Lund, 1842) dans le Pléistocène supérieur du Brésil intertropical. Comptes Rendus Palevol 13 (4), 2014, pp. 259-266

- ^ a b M. Susana Bargo, Gerardo de Iuliis and Sergio F. Vízcaino: Hypsodonty in Pleistocene ground sloths. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (1), 2006, pp. 53-61

- ^ a b c d e Giuseppe Tito: New remains of Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund, 1842) (Megatheriidae, Xenarthra) from the coastal region of Ecuador. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 26, 2008, pp. 424-434

- ^ Gerardo De Iuliis: Toward the morphofunctional understanding of the humerus of Megatheriinae: The identity and homology of some diaphyseal humeral features (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Megatheriidae). Senckenbergiana biologica 83, 2003, pp. 69-78

- ^ H. Gregory McDonald: Xenarthran skeletal anatomy: primitive or derived? Senckenbergiana biologica 83, 2003, pp. 5-17

- ^ Gerardo De Iuliis and Cástor Cartelle: The medial carpal and metacarpal elements of Eremotherium and Megatherium (Xenarthra: Mammalia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14, 1994, pp. 525-533

- ^ a b c Giuseppe Tito and Gerardo De Iuliis: Morphofunctional aspects and paleobiology of the manus in the giant ground sloth Eremotherium Spillmann 1948 (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Megatheriidae). Senckenbergiana biologica 83 (1), 2003, pp. 79-94

- ^ Diego Brandoni, Alfredo A. Carlini, Francois Pujos, and Gustavo J. Scillato-Yané: The pes of Pyramiodontherium bergi (Moreno & Mercerat, 1891) (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Phyllophaga): The most complete pes of a Tertiary Megatheriinae. Geodiversitas 26 (4), 2004, pp. 643–659

- ^ François Pujos and Rodolfo Salas: A systematic reassessment and paleogeographic review of fossil Xenarthra from Peru. Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines 33 (2), 2004, pp. 331-377

- ^ a b Bruno Andrés Than-Marchese, Luis Enrique Gomez-Perez, Jesús Albert Diaz-Cruz, Gerardo Carbot-Chanona and Marco Antonio Coutiño-José: Una nueva localidad con restos de Eremotherium laurillardi (Xenarthra: Megateriidae) in Chiapas, Mexico: possible evidence de gregarismo en la especie. VI Jornadas Paleontológicas y I Simposio de Paleontología en el Sureste de México: 100 years de paleontología en Chiapas, 2012, p. 50

- ^ a b McDonald, H. Gregory (June 2023). "A Tale of Two Continents (and a Few Islands): Ecology and Distribution of Late Pleistocene Sloths". Land. 12 (6): 1192. doi:10.3390/land12061192. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ^ França, Lucas de Melo; Araújo-Júnior, Hermínio Ismael de; Dantas, Mário André Trindade (1 August 2023). "Taphonomy, paleoecology and chronology of a late Quaternary tank (natural reservoir) deposit from the Brazilian Intertropical Region". Quaternary Science Reviews. 313: 108199. Bibcode:2023QSRv..31308199F. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108199. Retrieved 28 April 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ McDonald, H.G.; Lundelius, E.L., Jr. The giant ground sloth, Eremotherium laurillardi, (Xenarthra, Megatheriidae) in Texas. In Papers on Geology, Vertebrate Paleontology, and Biostratigraphy in Honor of Michael, O. Woodburne; Albright, L.B., III, Ed.; Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2009; Volume 65, pp. 407–421.

- ^ a b Carbot-Chanona, Gerardo; Gómez-Pérez, Luis Enrique; Coutiño-José, Marco Antonio (2022-07-30). "A new specimen of Eremotherium laurillardi (Xenarthra, Megatheriidae) from the Late Pleistocene of Chiapas, and comments about the distribution of the species in Mexico" (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 74 (2): A070322. doi:10.18268/BSGM2022v74n2a070322.

- ^ H. Gregory McDonald: Evolution of the Pedolateral Foot in Ground Sloths: Patterns of Change in the Astragalus. Journal of Mammal Evolution 19, 2012, pp. 209-215

- ^ Néstor Toledo, Gerardo De Iuliis, Sergio F. Vizcaíno and M. Susana Bargo: The Concept of a Pedolateral Pes Revisited: The Giant Sloths Megatherium and Eremotherium (Xenarthra, Folivora, Megatheriinae) as a Case Study. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 25 (4), 2018, pp. 525-537, doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9410-0

- ^ Barbosa, Fernando Henrique de Souza; Araújo-Júnior, Hermínio Ismael de; Oliveira, Edison Vicente (September 2014). "Neck osteoarthritis in Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund, 1842; Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Late Pleistocene of Brazil". International Journal of Paleopathology. 6: 60–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2014.01.001. PMID 29539579.

- ^ a b Emily L Lindsey, Erick X Lopez Reyes, Gordon E Matzke, Karin A Rice, and H Gregory McDonald: A monodominant late-Pleistocene megafauna locality from Santa Elena, Ecuador: Insight on the biology and behavior of giant ground sloths. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2020, p. 109599,

- ^ Hermínio Ismael de Araújo-Júnior, Kleberson de Oliveira Porpino, Celso Lira Ximenes and Lílian Paglarelli Bergqvist: Unveiling the taphonomy of elusive natural tank deposits: A study case in the Pleistocene of northeastern Brazil. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 378, 2013, pp. 52-74

- ^ Rodrigo L. Tomassini, Claudia I. Montalvo, Mariana C. Garrone, Laura Domingo, Jorge Ferigolo, Laura E. Cruz, Dánae Sanz-Pérez, Yolanda Fernández-Jalvo, and Ignacio A. Cerda: Gregariousness in the giant sloth Lestodon (Xenarthra ): multi‑proxy approach of a bonebed from the Last Maximum Glacial of Argentine pampas. Scientific Reports 10, 2020, p. 10955, doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67863-0

- ^ Adriano Garcia Chiarello: Sloth ecology. An overview of field studies. In: Sergio F. Vizcaíno and WJ Loughry (eds.): The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida, 2008, pp. 269-280

- ^ Sergio F Vizcaíno, M Susana Bargo and Guillermo H Cassini: Dental occlusal surface area in relation to body mass, food habits and other biological features in fossil xenarthrans. Ameghiniana 43 (1), 2006, pp. 11-26

- ^ Mário AT Dantas and Adaiana MA Santos: Inferring the paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene giant ground sloths from the Brazilian Intertropical Region. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 117, 2022, p.103899, doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103899

- ^ Mário André Trindade Dantas, Rodrigo Parisi Dutra, Alexander Cherkinsky, Daniel Costa Fortier, Luciana Hiromi Yoshino Kamino, Mario Alberto Cozzuol, Adauto de Souza Ribeiro and Fabiana Silva Vieira: Paleoecology and radiocarbon dating of the Pleistocene megafauna of the Brazilian Intertropical Region. Quaternary Research 79, 2013, pp. 61-65

- ^ Oliveira, Jacqueline Freitas; Asevedo, Lidiane; Cherkinsky, Alexander; Dantas, M.A.T (October 2020). "Radiocarbon dating and integrative paleoecology (ẟ13C, stereomicrowear) of Eremotherium laurillardi (LUND, 1842) from midwest region of the Brazilian intertropical region". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 102: 102653. Bibcode:2020JSAES.10202653O. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102653. S2CID 219912019.

- ^ Lindsey, Emily L.; Lopez Reyes, Erick X.; Matzke, Gordon E.; Rice, Karin A.; McDonald, H. Gregory (April 2020). "A monodominant late-Pleistocene megafauna locality from Santa Elena, Ecuador: Insight on the biology and behavior of giant ground sloths". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 544: 109599. Bibcode:2020PPP...54409599L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109599.

- ^ da Silva, Rodolfo C.; de S. Barbosa, Fernando H.; de O. Porpino, Kleberson (December 2023). "New paleopathological findings from the Quaternary of the Brazilian Intertropical Region expand the distribution of joint diseases for the South American megafauna". International Journal of Paleopathology. 43: 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2023.08.002. PMID 37716107. Retrieved 1 May 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Barbosa, Fernando Henrique de Souza; Araújo-Júnior, Hermínio Ismael de (October 2021). "Skeletal pathologies in the giant ground sloth Eremotherium laurillardi (Xenarthra, Folivora): New cases from the Late Pleistocene of Brazil". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 110: 103377. Bibcode:2021JSAES.11003377B. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103377. Retrieved 9 May 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ De Iuliis, Gerardo; Pujos, François; Tito, Giuseppe (12 December 2009). "Systematic and taxonomic revision of the Pleistocene ground sloth Megatherium (Pseudomegatherium) tarijense (Xenarthra: Megatheriidae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1244–1251. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1244D. doi:10.1671/039.029.0426. S2CID 84272333.

- ^ Gaudin, Timothy J. (February 2004). "Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140 (2): 255–305. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x. S2CID 38722942.

- ^ Delsuc, Frédéric; Kuch, Melanie; Gibb, Gillian C.; Karpinski, Emil; Hackenberger, Dirk; Szpak, Paul; Martínez, Jorge G.; Mead, Jim I.; McDonald, H. Gregory; MacPhee, Ross D.E.; Billet, Guillaume; Hautier, Lionel; Poinar, Hendrik N. (June 2019). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E2031D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. hdl:11336/136908. PMID 31178321. S2CID 177661447.

- ^ Presslee, Samantha; Slater, Graham J.; Pujos, François; Forasiepi, Analía M.; Fischer, Roman; Molloy, Kelly; Mackie, Meaghan; Olsen, Jesper V.; Kramarz, Alejandro; Taglioretti, Matías; Scaglia, Fernando; Lezcano, Maximiliano; Lanata, José Luis; Southon, John; Feranec, Robert; Bloch, Jonathan; Hajduk, Adam; Martin, Fabiana M.; Salas Gismondi, Rodolfo; Reguero, Marcelo; de Muizon, Christian; Greenwood, Alex; Chait, Brian T.; Penkman, Kirsty; Collins, Matthew; MacPhee, Ross D. E. (6 June 2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3.1121P. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Marshall, Lawrence G. (July 1988). "Land Mammals and the Great American Interchange". American Scientist. 76 (4): 380–388. Bibcode:1988AmSci..76..380M.

- ^ Brandoni, Diego; Ruiz, Laureano González; Bucher, Joaquín (September 2020). "Evolutive Implications of Megathericulus patagonicus (Xenarthra, Megatheriinae) from the Miocene of Patagonia Argentina". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 27 (3): 445–460. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09469-6. S2CID 254695811.

- ^ Varela, Luciano; Tambusso, P Sebastián; McDonald, H Gregory; Fariña, Richard A (1 March 2019). "Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis". Systematic Biology. 68 (2): 204–218. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy058. PMID 30239971.

- ^ Rossetti, Dilce de Fátima; Toledo, Peter Mann de; Moraes-Santos, Heloı́sa Maria; Santos, Antônio Emı́dio de Araújo (2004). "Reconstructing habitats in central Amazonia using megafauna, sedimentology, radiocarbon, and isotope analyses". Quaternary Research. 61 (3): 289–300. Bibcode:2004QuRes..61..289D. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2004.02.010. S2CID 140688069.

- ^ Dantas, Mário André Trindade; de Queiroz, Albérico Nogueira; Vieira dos Santos, Fabiana; Cozzuol, Mario Alberto (March 2012). "An anthropogenic modification in an Eremotherium tooth from northeastern Brazil". Quaternary International. 253: 107–109. Bibcode:2012QuInt.253..107D. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.09.019.

- ^ Hubbe, Alex; Haddad-Martim, Paulo M.; Hubbe, Mark; Neves, Walter A. (August 2012). "Comments on: 'An anthropogenic modification in an Eremotherium tooth from northeastern Brazil'". Quaternary International. 269: 94–96. Bibcode:2012QuInt.269...94H. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.01.029.

- Prehistoric sloths

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Pliocene xenarthrans

- Pleistocene xenarthrans

- Zanclean first appearances

- Holocene extinctions

- Pliocene mammals of North America

- Pleistocene mammals of North America

- Rancholabrean

- Irvingtonian

- Blancan

- Neogene Costa Rica

- Neogene United States

- Pleistocene Costa Rica

- Pleistocene El Salvador

- Pleistocene Guatemala

- Pleistocene Honduras

- Pleistocene Mexico

- Pleistocene Nicaragua

- Pleistocene Panama

- Pleistocene United States

- Fossils of Costa Rica

- Fossils of El Salvador

- Fossils of Guatemala

- Fossils of Honduras

- Fossils of Mexico

- Fossils of Nicaragua

- Fossils of Panama

- Fossils of the United States

- Pliocene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Lujanian

- Ensenadan

- Uquian

- Chapadmalalan

- Montehermosan

- Neogene Venezuela

- Pleistocene Bolivia

- Pleistocene Brazil

- Pleistocene Colombia

- Pleistocene Ecuador

- Pleistocene Venezuela

- Fossils of Bolivia

- Fossils of Brazil

- Fossils of Colombia

- Fossils of Ecuador

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Fossil taxa described in 1948

- Taxa named by Peter Wilhelm Lund