Félix I

Félix I (officially "F-360-BD") was a Brazilian Army Technical School (today's Military Institute of Engineering[1]) project led by Lieutenant Colonel Manoel dos Santos Lage which aimed, in 1959, to launch the Flamengo cat into space. But the project was canceled due to pressure from animal advocacy groups, and the launch never took place.

History

Origins

The project, also known as "Operation Meow",[2] with limited financial resources, was part of the graduation class of 1958 of the Army Technical School that aimed to create a sounding rocket, something unheard of in Brazil at the time.[3][4] The official name was "Rocket Sonda 360-BD", unrelated to the later Sonda I.[5]

The rocket had an outer diameter of 400 mm, a length of 4.3 meters, and a total mass of 350 kg with the payload, and it used only a single stage and was propelled by gunpowder,[6] reaching a maximum speed of 1.950 m/s.[7] Lieutenant-Colonel Myearel dos Santos Lage's ultimate goal,[a] head of the Rocket Program and leader of the project, but not shared by the institution, was to develop a satellite launch vehicle.[10][4] The project also had the collaboration of scientists Carlos Chagas Filho and César Lattes.[11] Carlos Chagas Filho was responsible for the idea of choosing a cat, because he was interested in observing how these animals reacted under laboratory conditions.[12] Most of the material used to build the rocket was obtained from the War Arsenal.[2]

The project, which aimed to test a guided missile costing Cr$600,000,[b] was nicknamed "Felix I" by the Rio de Janeiro press after they discovered their intention to launch a cat, Flamengo, into space. Originally they planned for the rocket to reach the 300 km mark, but this was abandoned due to difficulties in the calculations.[10][14][15] The final decision was that the class of 1958 would develop a rocket that reached an apogee of 120 km and the class of 1950 would work on one that reached 300 km, with the ultimate goal of developing a Thor-type rocket that would reach orbits greater than 500 km by June 1960.[16][4]

Initially the rocket was to be launched in 1957, but it was delayed twice and by December 1958 they hoped to launch in early January 1959.[4]

Flight plan

The rocket would be launched from a base in Cabo Frio. Its accelerometer would be connected to a transmitter at a frequency of 73 Mc/s.[17] César Lattes was responsible for building three transmitters and the instruments aimed at cosmic ray detection;[c] Lieutenant-Colonel Carlos Alberto Braga Coelho built the electronics of the rocket; Carlos Chagas Filho (IBCCF) developed the instruments for monitoring the cat's health; and astronomer Mário Ferreira Dias, from the Valongo Observatory, developed the calculations related to the flight.[19]

The combustion chamber was built by the Army War Arsenal in company with the students of the Armaments Course, with the carbon steel plate produced by the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional. The rocket was painted silver with red stripes in a spiral, to help the visibility of the rocket in flight, as the process would be monitored by the National Observatory.[7]

The rocket thrust was predicted to be 1,920 kgf with 6G of acceleration, 19.3s of combustion, and a final velocity of 1,960 m/s. The propellant, developed by the Army Technical School, was called "BD 1000C Gunpowder".[20] The rocket would carry a 180-kilogram payload of gunpowder to reach the ionosphere.[4]

The payload fairing, with a final mass of 30 kg, would contain an acrylic chamber for the cat, as well as the other instruments for the mission. The chamber, with the return speed estimated at 1,800 m/s,[21] would initially be rescued by two air braking devices, and would be followed by a 68 kg parachute developed by the Army Air Ground Division Core, open at an altitude of 5,000 meters,[22] all in an automatic way.[23] The cat would have four hours of oxygen[12] and would be placed face up on a nylon mattress. The flight would last 40 minutes, falling into the sea 30 kilometers from the launch pad, off Angra dos Reis, and would be rescued by the Brazilian Navy. Rescuing the cat alive was considered the greatest challenge of the project.[4][24] The rocket stages would be rescued by two parachutes.[25] Finally, the flight date would be analyzed by César Lattes.[26]

If the mission was successful, the future rockets would be made available to the National Nuclear Energy Council and the Biophysics Institute for scientific research.[27]

Flamengo

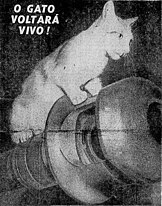

Flamengo,[d] popularly known as "Meow",[29] the tomcat of Lieutenant-Colonel Lage's daughters, was one of the twelve candidates for the flight. He was the leading candidate and would only be released if he was in good health on the day of the flight[4][30] and his presence on the flight was already confirmed in December 1958.[28] But in October 1958, the Diário do Paraná announced that Carlos Chagas Filho would replace the animal with an amoeba, arguing that a microscopic animal would be of greater scientific use in the study of cosmic rays.[31][32] Despite this, Colonel Lage kept the cat in the project[33] and when asked in 1959 about the reason for launching the cat, he replied: "... the recovery of this cat, alive, will be an extraordinary achievement".[14][e] On 19 December 1958 the cat posed for the media inside the Technical School.[34] If the launch had taken place, it would have been Latin America's first living being in space.[35]

Controversy

Carlos Chagas Filho, when the experiment began to gain visibility in the media, renounced any renewed interest in sending a cat on the mission and the possibility of any scientific learning, besides citing that the acrylic capsule would face difficulties with drastic temperature changes.[33][32]

In addition to the disagreement with Carlos Chagas Filho, the project team received protests from the "North American Feline Society," something that the project manager disregarded, believing in the safety of the vehicle. The SUIPA also opposed the use of the cat.[36][37]

Members of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and other experts were also skeptical of Flamengo's chances of survival, and Leo Rosen, vice president of SUIPA, also reiterated the group's position against the experiment[38] SUIPA also sent an appeal and a petition, signed by, among others, Rachel de Queiroz and Carlos Drummond de Andrade, to the Commander of the Army Technical School and to the Minister of War, General Teixeira Lott, against launching the cat in the rocket.[39][30][40] On the issue of animal experiments, SUIPA only advocated when extremely necessary, and was skeptical of the need for the cat experiment.[41] The Brazilian government received thousands of letters protesting against the experiment, but the Army ignored them.[13] And despite all the protests, including from Europe, the project leader continued with his plans.[28][42]

In November 1958 it was announced that the launch would be held in secret to "avoid sensationalism"[15] and in the same month Colonel João Luís Vieira Maldonado, director of the Meteorology Service, said that the rocket would only carry sounding devices, and no longer the cat.[43] However, in January 1959, Colonel Lage still hoped to make the launch with the cat[14] and in February of the same year they planned to launch in March.[44] However, in May 1959, the launch had not yet occurred and freshmen from the National Engineering School held a parade where, among other things, they criticized and satirized the project.[45] In December 1958 the Army announced that it would test a prototype of the rocket before the official launch.[46]

End of project

In January 1959 the rocket was on display at the Armament Museum of the Army Technical School.[8] By 1961 it was already clear that the launch had not taken place.[47][f] It was the last rocket project that Colonel Lage participated in[49] and was terminated without flying.[50] Finally, on 18 October 1963, the cat Félicette made a suborbital flight as part of the French space program, returned alive, and was sacrificed after two months for an autopsy and study of her brain.[51] Colonel Lage was transferred from the Army Technical School in 1960 and all the equipment related to the rocket was disassembled.[52] Myearel Lage, already a General, born on 4 June 1910, died on 5 August 1977.[53] The Army Technical School was abolished in favor of the Military Institute of Engineering.[54]

Because of the project, at that time Brazil was considered one of the three countries with space technology, alongside the United States and the Soviet Union.[55] In terms of satellite launch capabilities, years later Brazil developed the unsuccessful VLS project, terminated in 2016. The country is currently working on the VLM project.[56]

See also

Notes

- ^ In 1951, as an artillery officer, Manoel dos Santos Lage designed, built and launched, as part of the Army Technical School, Brazil's first single-stage rocket.[8] In 1958 he was responsible for the first Brazilian two-stage rocket.[9]

- ^ About $1500.[13]

- ^ Cosmic-ray instruments posed a miniaturization challenge.[18]

- ^ Name in reference to Associação Atlética Flamengo.[28]

- ^ Original: "... a recuperação desse gato, vivo, será um feito extraordinário".

- ^ In 1968, in Ceará, there was a similar project.[48]

References

- ^ IME, História.

- ^ a b Diario de Noticias, 23 de dezembro de 1958b, p. 14.

- ^ Silva 2020, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c d e f g Diário de Pernambuco, 19 de dezembro de 1958, p. 15.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 96.

- ^ Silva 2020, pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Silva 2020, p. 101.

- ^ a b Manchete, 24 de janeiro de 1959, p. 68.

- ^ Manchete, 4 de janeiro de 1958, p. 67.

- ^ a b Silva 2020, p. 97.

- ^ Silva 2020, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Silva 2020, p. 108.

- ^ a b Spokane Daily Chronicle, 31 de dezembro de 1958, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Manchete, 24 de janeiro de 1959, p. 69.

- ^ a b Diario Carioca, 1 de novembro de 1958, p. 12.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 98.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 99.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 111.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 100.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 103.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 107.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 105.

- ^ Silva 2020, pp. 107, 111.

- ^ Diário de Notícias, 18 de dezembro de 1958, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Ultima Hora, 18 de dezembro de 1958, p. 7.

- ^ Silva 2020, p. 112.

- ^ Diário de Notícias, 29 de outubro de 1958, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Tribuna da Imprensa, 20-21 de dezembro de 1959, p. 7.

- ^ Diario de Noticias, 23 de dezembro de 1958a, p. 1.

- ^ a b Tribuna da Imprensa, 18 de dezembro de 1958, p. 1.

- ^ Diario do Paraná, 28 de outubro de 1958, p. 1.

- ^ a b Diario do Parana, 5 de novembro de 1958, p. 1.

- ^ a b Silva 2020, p. 110.

- ^ Jornal do Brasil, 16 de dezembro de 1958, p. 7.

- ^ Izola 1994, p. 50.

- ^ Última Hora, 1 de novembro de 1958, p. 1.

- ^ O Jornal, 31 de outubro de 1958, p. 4.

- ^ Diário de Notícias, 20 de dezembro de 1958, p. 15.

- ^ Luta Democratica, 20 de dezembro de 1958, p. 5.

- ^ O Jornal, 20 de dezembro de 1958, p. 5.

- ^ Diario Carioca, 21-22 de dezembro de 1958, p. 8.

- ^ Tribuna da Imprensa, 20-21 de dezembro de 1959, p. 1, Inglaterra protesta contra gato no foguete.

- ^ Tribuna da Imprensa, 14 de novembro de 1958, p. 5.

- ^ Última Hora, 3 de fevereiro de 1959, p. 7.

- ^ Jornal do Brasil, 16 de maio de 1959, p. 7.

- ^ Diário de Notícias, 18 de dezembro de 1958, p. 1.

- ^ Diario Carioca, 12 de maio de 1963, p. 11.

- ^ O Jornal, 10 de julho de 1968, p. 9.

- ^ Izola 1994, p. 53.

- ^ Izola 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Folha de São Paulo, 17 de julho de 2019.

- ^ Izola 1994, p. 63.

- ^ Silva 2020, pp. 27, 46.

- ^ Izola 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Izola 1994, p. 49.

- ^ Revista Fapesp, janeiro de 2022.

Bibliography

(Chronological order)

- Lemos, Carlos (4 January 1958). "Foguete tupiniquim aprovado com grau 10". Manchete (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 5, no. 298. pp. 64–67.

- "Ameba substituirá gato no foguete". Diário do Paraná (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 4, no. 1084. 28 October 1958. p. 1.

- "Foguete de três estágios". Diário de Notícias (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 34, no. 203. 29 October 1958. p. 14.

- "Gato no foguete brasileiro vai causar protesto". O Jornal (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 37, no. 11705. 31 October 1958. p. 4.

- "Tem gato na tuba: Exército, Físico e S.U.I.P.A. divergem sôbre o animal do foguete". Última Hora (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 8, no. 2557. 1 November 1958. p. 2.

- "O 'Gato Voador' será lançado em segredo". Diario Carioca (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 31, no. 9297. 1 November 1958. p. 11.

- "Virus e Celulas em Lugar do Gato: Foguete". Diario do Paraná (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 4, no. 1091. 5 November 1958. p. 1.

- "Em lugar de gato foguete levará aparelhos de sondagem". Tribuna da Imprensa (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 10, no. 2694. 14 November 1958. p. 5.

- "Gato do 'Félix I" posa sexta-feita". Jornal do Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 68, no. 294. 16 December 1958. p. 7.

- "SUIPA não quer gato no foguete". Tribuna da Imprensa (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 10, no. 2722. 18 December 1958. p. 1.

- "O Exército Testará Antes Um Protótipo do Foguete". Diário de Notícias (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 39, no. 11073. 18 December 1958. pp. 1–2.

- "Adiada a viagem: foguete (com gato dentro) só será lançado em janeiro". Ultima Hora (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 8, no. 11. 18 December 1958. p. 7.

- "Flamengo o candidato mais forte a ser lançado no Félix I de patas pra cima". Diário de Pernambuco (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 134, no. 288. 19 December 1958. p. 15.

- ""Flamengo" não sobreviverá!". Diário de Notícias (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 34, no. 248. 20 December 1958. p. 15.

- "Toma vulto o protesto contra a remessa do gato no foguete". O Jornal (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 37, no. 11750. 20 December 1958. p. 5.

- "Apêlo ao Exército para que não ponha o gato no foguete". Luta Democratica (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 5, no. 1497. 20 December 1958. p. 5.

- "A S.U.I.P.A. é quem fala por êles". Diario Carioca (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 31, no. 9340. 21 December 1958. p. 8.

- "Flamengo descerá de pára-quedas no vôo que realizará no "Félix I"". Diário de Notícias (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 34, no. 250. 23 December 1958. p. 1.

- "J". Diário de Notícias (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 34, no. 250. 23 December 1958. p. 14.

- "SUIPA não impedirá viagem do "Flamengo"". Tribuna da Imprensa (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 10, no. 2724. December 1958. p. 7.

- "Brazil Getting Ready to Fire Cat in Space". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Vol. 73, no. 87. 31 December 1958. p. 12.

- Carlos, Newton (24 January 1959). "O "Félix I" vai ganhar um irmão teleguiado". Manchete (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 7, no. 353. pp. 66–69.

- "Félix em março". Última Hora (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 7, no. 2091. 3 February 1959. p. 7.

- "Calouros desfilaram com Delgado e Fidel Castro". Jornal do Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 61, no. 113. 16 May 1959. p. 7.

- "Na Estratosfera". Diario Carioca (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 33, no. 10085. 12 May 1961. p. 11.

- "Ceará entra na corrida espacial". O Jornal (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 41, no. 14350. 10 July 1968. p. 9.

- Izola, Dawson Tadeu (1994). História dos Foguetes no Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese) (1 ed.). FATEC-SP. p. 87.

- Haidar, Sílvia (17 July 2019). "Félicette, primeira gata a fazer uma viagem espacial, teve sua história praticamente esquecida". Folha de São Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- Silva, Bernardino Coelho da (2020). Coronel Lage (in Brazilian Portuguese). Clube de Autores. p. 270. ISBN 9786500136357.

- Zaparolli, Domingos (January 2022). "Launch remains distant". Revista Fapesp (311 ed.).

- "História do Instituto Militar de Engenharia". ime.eb.mil.br (in Brazilian Portuguese).