Fluorescent tag

In molecular biology and biotechnology, a fluorescent tag, also known as a fluorescent label or fluorescent probe, is a molecule that is attached chemically to aid in the detection of a biomolecule such as a protein, antibody, or amino acid. Generally, fluorescent tagging, or labeling, uses a reactive derivative of a fluorescent molecule known as a fluorophore. The fluorophore selectively binds to a specific region or functional group on the target molecule and can be attached chemically or biologically.[1] Various labeling techniques such as enzymatic labeling, protein labeling, and genetic labeling are widely utilized. Ethidium bromide, fluorescein and green fluorescent protein are common tags. The most commonly labelled molecules are antibodies, proteins, amino acids and peptides which are then used as specific probes for detection of a particular target.[2]

History

The development of methods to detect and identify biomolecules has been motivated by the ability to improve the study of molecular structure and interactions. Before the advent of fluorescent labeling, radioisotopes were used to detect and identify molecular compounds. Since then, safer methods have been developed that involve the use of fluorescent dyes or fluorescent proteins as tags or probes as a means to label and identify biomolecules.[3] Although fluorescent tagging in this regard has only been recently utilized, the discovery of fluorescence has been around for a much longer time.

Sir George Stokes developed the Stokes Law of Fluorescence in 1852 which states that the wavelength of fluorescence emission is greater than that of the exciting radiation. Richard Meyer then termed fluorophore in 1897 to describe a chemical group associated with fluorescence. Since then, Fluorescein was created as a fluorescent dye by Adolph von Baeyer in 1871 and the method of staining was developed and utilized with the development of fluorescence microscopy in 1911.[4]

Ethidium bromide and variants were developed in the 1950s,[4] and in 1994, fluorescent proteins or FPs were introduced.[5] Green fluorescent protein or GFP was discovered by Osamu Shimomura in the 1960s and was developed as a tracer molecule by Douglas Prasher in 1987.[6] FPs led to a breakthrough of live cell imaging with the ability to selectively tag genetic protein regions and observe protein functions and mechanisms.[5] For this breakthrough, Shimomura was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2008.[7]

New methods for tracking biomolecules have been developed including the use of colorimetric biosensors, photochromic compounds, biomaterials, and electrochemical sensors. Fluorescent labeling is also a common method in which applications have expanded to enzymatic labeling, chemical labeling, protein labeling, and genetic labeling.[1]

Methods for tracking biomolecules

There are currently several labeling methods for tracking biomolecules. Some of the methods include the following.

Isotope markers

Common species that isotope markers are used for include proteins. In this case, amino acids with stable isotopes of either carbon, nitrogen, or hydrogen are incorporated into polypeptide sequences.[8] These polypeptides are then put through mass spectrometry. Because of the exact defined change that these isotopes incur on the peptides, it is possible to tell through the spectrometry graph which peptides contained the isotopes. By doing so, one can extract the protein of interest from several others in a group. Isotopic compounds play an important role as photochromes, described below.

Colorimetric biosensors

Biosensors are attached to a substance of interest. Normally, this substance would not be able to absorb light, but with the attached biosensor, light can be absorbed and emitted on a spectrophotometer.[9] Additionally, biosensors that are fluorescent can be viewed with the naked eye. Some fluorescent biosensors also have the ability to change color in changing environments (ex: from blue to red). A researcher would be able to inspect and get data about the surrounding environment based on what color he or she could see visibly from the biosensor-molecule hybrid species.[10]

Colorimetric assays are normally used to determine how much concentration of one species there is relative to another.[9]

Photochromic compounds

Photochromic compounds have the ability to switch between a range or variety of colors. Their ability to display different colors lies in how they absorb light. Different isomeric manifestations of the molecule absorbs different wavelengths of light, so that each isomeric species can display a different color based on its absorption. These include photoswitchable compounds, which are proteins that can switch from a non-fluorescent state to that of a fluorescent one given a certain environment.[11]

The most common organic molecule to be used as a photochrome is diarylethene.[12] Other examples of photoswitchable proteins include PADRON-C, rs-FastLIME-s and bs-DRONPA-s, which can be used in plant and mammalian cells alike to watch cells move into different environments.[11]

Biomaterials

Fluorescent biomaterials are a possible way of using external factors to observe a pathway more visibly. The method involves fluorescently labeling peptide molecules that would alter an organism's natural pathway. When this peptide is inserted into the organism's cell, it can induce a different reaction. This method can be used, for example to treat a patient and then visibly see the treatment's outcome.[13]

Electrochemical sensors

Electrochemical sensors can be used for label-free sensing of biomolecules. They detect changes and measure current between a probed metal electrode and an electrolyte containing the target analyte. A known potential to the electrode is then applied from a feedback current and the resulting current can be measured. For example, one technique using electrochemical sensing includes slowly raising the voltage causing chemical species at the electrode to be oxidized or reduced. Cell current vs voltage is plotted which can ultimately identify the quantity of chemical species consumed or produced at the electrode.[14] Fluorescent tags can be used in conjunction with electrochemical sensors for ease of detection in a biological system.

Fluorescent labels

Of the various methods of labeling biomolecules, fluorescent labels are advantageous in that they are highly sensitive even at low concentration and non-destructive to the target molecule folding and function.[1]

Green fluorescent protein is a naturally occurring fluorescent protein from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria that is widely used to tag proteins of interest. GFP emits a photon in the green region of the light spectrum when excited by the absorption of light. The chromophore consists of an oxidized tripeptide -Ser^65-Tyr^66-Gly^67 located within a β barrel. GFP catalyzes the oxidation and only requires molecular oxygen. GFP has been modified by changing the wavelength of light absorbed to include other colors of fluorescence. YFP or yellow fluorescent protein, BFP or blue fluorescent protein, and CFP or cyan fluorescent protein are examples of GFP variants. These variants are produced by the genetic engineering of the GFP gene.[15]

Synthetic fluorescent probes can also be used as fluorescent labels. Advantages of these labels include a smaller size with more variety in color. They can be used to tag proteins of interest more selectively by various methods including chemical recognition-based labeling, such as utilizing metal-chelating peptide tags, and biological recognition-based labeling utilizing enzymatic reactions.[16] However, despite their wide array of excitation and emission wavelengths as well as better stability, synthetic probes tend to be toxic to the cell and so are not generally used in cell imaging studies.[1]

Fluorescent labels can be hybridized to mRNA to help visualize interaction and activity, such as mRNA localization. An antisense strand labeled with the fluorescent probe is attached to a single mRNA strand, and can then be viewed during cell development to see the movement of mRNA within the cell.[17]

Fluorogenic labels

A fluorogen is a ligand (fluorogenic ligand) which is not itself fluorescent, but when it is bound by a specific protein or RNA structure becomes fluorescent.[18]

For instance, FAST is a variant of photoactive yellow protein which was engineered to bind chemical mimics of the GFP tripeptide chromophore.[19] Likewise, the spinach aptamer is an engineered RNA sequence which can bind GFP chromophore chemical mimics, thereby conferring conditional and reversible fluorescence on RNA molecules containing the sequence.[20]

Use of tags in fluorescent labeling

Fluorescent labeling is known for its non-destructive nature and high sensitivity. This has made it one of the most widely used methods for labeling and tracking biomolecules.[1] Several techniques of fluorescent labeling can be utilized depending on the nature of the target.

Enzymatic labeling

In enzymatic labeling, a DNA construct is first formed, using a gene and the DNA of a fluorescent protein.[21] After transcription, a hybrid RNA + fluorescent is formed. The object of interest is attached to an enzyme that can recognize this hybrid DNA. Usually fluorescein is used as the fluorophore.

Chemical labeling

Chemical labeling or the use of chemical tags utilizes the interaction between a small molecule and a specific genetic amino acid sequence.[22] Chemical labeling is sometimes used as an alternative for GFP. Synthetic proteins that function as fluorescent probes are smaller than GFP's, and therefore can function as probes in a wider variety of situations. Moreover, they offer a wider range of colors and photochemical properties.[23] With recent advancements in chemical labeling, Chemical tags are preferred over fluorescent proteins due to the architectural and size limitations of the fluorescent protein's characteristic β-barrel. Alterations of fluorescent proteins would lead to loss of fluorescent properties.[22]

Protein labeling

Protein labeling use a short tag to minimize disruption of protein folding and function. Transition metals are used to link specific residues in the tags to site-specific targets such as the N-termini, C-termini, or internal sites within the protein. Examples of tags used for protein labeling include biarsenical tags, Histidine tags, and FLAG tags.[1]

Genetic labeling

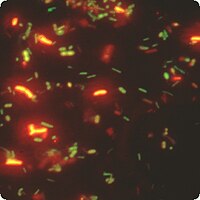

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), is an example of a genetic labeling technique that utilizes probes that are specific for chromosomal sites along the length of a chromosome, also known as chromosome painting. Multiple fluorescent dyes that each have a distinct excitation and emission wavelength are bound to a probe which is then hybridized to chromosomes. A fluorescence microscope can detect the dyes present and send it to a computer that can reveal the karyotype of a cell. This technique allows abnormalities such as deletions and duplications to be revealed.[24]

Cell imaging

Chemical tags have been tailored for imaging technologies more so than fluorescent proteins because chemical tags can localize photosensitizers closer to the target proteins.[25] Proteins can then be labeled and detected with imaging such as super-resolution microscopy, Ca2+-imaging, pH sensing, hydrogen peroxide detection, chromophore assisted light inactivation, and multi-photon light microscopy. In vivo imaging studies in live animals have been performed for the first time with the use of a monomeric protein derived from the bacterial haloalkane dehalogenase known as the Halo-tag.[22][26] The Halo-tag covalently links to its ligand and allows for better expression of soluble proteins.[26]

Advantages

Although fluorescent dyes may not have the same sensitivity as radioactive probes, they are able to show real-time activity of molecules in action.[27] Moreover, radiation and appropriate handling is no longer a concern.

With the development of fluorescent tagging, fluorescence microscopy has allowed the visualization of specific proteins in both fixed and live cell images. Localization of specific proteins has led to important concepts in cellular biology such as the functions of distinct groups of proteins in cellular membranes and organelles. In live cell imaging, fluorescent tags enable movements of proteins and their interactions to be monitored.[24]

Latest advances in methods involving fluorescent tags have led to the visualization of mRNA and its localization within various organisms. Live cell imaging of RNA can be achieved by introducing synthesized RNA that is chemically coupled with a fluorescent tag into living cells by microinjection. This technique was used to show how the oskar mRNA in the Drosophila embryo localizes to the posterior region of the oocyte.[17]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Sahoo, Harekrushna (1 January 2012). "Fluorescent labeling techniques in biomolecules: a flashback". RSC Advances. 2 (18): 7017–7029. Bibcode:2012RSCAd...2.7017S. doi:10.1039/C2RA20389H.

- ^ "Fluorescent labeling of biomolecules with organic probes - Presentations - PharmaXChange.info". 29 January 2011.

- ^ Gwynne and Page, Peter and Guy. "Laboratory Technology Trends: Fluorescence + Labeling". Science. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ a b Kricka LJ, Fortina P (April 2009). "Analytical ancestry: "firsts" in fluorescent labeling of nucleosides, nucleotides, and nucleic acids". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (4): 670–83. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.116152. PMID 19233914.

- ^ a b Jing C, Cornish VW (September 2011). "Chemical tags for labeling proteins inside living cells". Accounts of Chemical Research. 44 (9): 784–92. doi:10.1021/ar200099f. PMC 3232020. PMID 21879706.

- ^ "Green Fluorescent Protein - GFP History - Osamu Shimomura".

- ^ Shimomura, Osamu. "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry". Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ Chen X, Smith LM, Bradbury EM (March 2000). "Site-specific mass tagging with stable isotopes in proteins for accurate and efficient protein identification". Analytical Chemistry. 72 (6): 1134–43. doi:10.1021/ac9911600. PMID 10740850.

- ^ a b "Colorimetric Assays". Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Halevy, Revital; Sofiya Kolusheval; Robert E.W. Hancock; Raz Jelinek (2002). "Colorimetric Biosensor Vesicles for Biotechnological Applications" (PDF). Materials Research Society Symposium Proceedings. 724. Biological and Biomimetic Materials - Properties to Function. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ a b Lummer M, Humpert F, Wiedenlübbert M, Sauer M, Schüttpelz M, Staiger D (September 2013). "A new set of reversibly photoswitchable fluorescent proteins for use in transgenic plants". Molecular Plant. 6 (5): 1518–30. doi:10.1093/mp/sst040. PMID 23434876.

- ^ Perrier A, Maurel F, Jacquemin D (August 2012). "Single molecule multiphotochromism with diarylethenes". Accounts of Chemical Research. 45 (8): 1173–82. doi:10.1021/ar200214k. PMID 22668009.

- ^ Zhang Y, Yang J (January 2013). "Design Strategies for Fluorescent Biodegradable Polymeric Biomaterials". Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 1 (2): 132–148. doi:10.1039/C2TB00071G. PMC 3660738. PMID 23710326.

- ^ "bioee.ee.columbia.edu" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-12-20.

- ^ Cox, Michael; Nelson, David R.; Lehninger, Albert L (2008). Lehninger principles of biochemistry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-7108-1.

- ^ Jung D, Min K, Jung J, Jang W, Kwon Y (May 2013). "Chemical biology-based approaches on fluorescent labeling of proteins in live cells". Molecular BioSystems. 9 (5): 862–72. doi:10.1039/c2mb25422k. PMID 23318293.

- ^ a b Weil TT, Parton RM, Davis I (July 2010). "Making the message clear: visualizing mRNA localization". Trends in Cell Biology. 20 (7): 380–90. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.006. PMC 2902723. PMID 20444605.

- ^ Szent-Gyorgyi C, Schmidt BF, Schmidt BA, Creeger Y, Fisher GW, Zakel KL, Adler S, Fitzpatrick JA, Woolford CA, Yan Q, Vasilev KV, Berget PB, Bruchez MP, Jarvik JW, Waggoner A (February 2008). "Fluorogen-activating single-chain antibodies for imaging cell surface proteins". Nature Biotechnology (Abstract). 26 (2): 235–40. doi:10.1038/nbt1368. PMID 18157118. S2CID 21815631.

We report here the development of protein reporters that generate fluorescence from otherwise dark molecules (fluorogens).

- ^ Plamont MA, Billon-Denis E, Maurin S, Gauron C, Pimenta FM, Specht CG, Shi J, Quérard J, Pan B, Rossignol J, Moncoq K, Morellet N, Volovitch M, Lescop E, Chen Y, Triller A, Vriz S, Le Saux T, Jullien L, Gautier A (January 2016). "Small fluorescence-activating and absorption-shifting tag for tunable protein imaging in vivo". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (3): 497–502. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..497P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513094113. PMC 4725535. PMID 26711992.

- ^ Paige JS, Wu KY, Jaffrey SR (July 2011). "RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein". Science. 333 (6042): 642–6. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..642P. doi:10.1126/science.1207339. PMC 3314379. PMID 21798953.

- ^ Richter A, Schwager C, Hentze S, Ansorge W, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler M (September 2002). "Comparison of fluorescent tag DNA labeling methods used for expression analysis by DNA microarrays" (PDF). BioTechniques. 33 (3): 620–8, 630. doi:10.2144/02333rr05. PMID 12238772.

- ^ a b c Wombacher R, Cornish VW (June 2011). "Chemical tags: applications in live cell fluorescence imaging". Journal of Biophotonics. 4 (6): 391–402. doi:10.1002/jbio.201100018. PMID 21567974.

- ^ Jung D, Min K, Jung J, Jang W, Kwon Y (May 2013). "Chemical biology-based approaches on fluorescent labeling of proteins in live cells". Molecular BioSystems. 9 (5): 862–72. doi:10.1039/C2MB25422K. PMID 23318293.

- ^ a b Matthew P Scott; Lodish, Harvey F.; Arnold Berk; Kaiser, Chris; Monty Krieger; Anthony Bretscher; Hidde Ploegh; Angelika Amon (2012). Molecular Cell Biology. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-3413-9.

- ^ Ettinger, A (2014). "Fluorescence live cell imaging". Quantitative Imaging in Cell Biology. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 123. pp. 77–94. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420138-5.00005-7. ISBN 9780124201385. PMC 4198327. PMID 24974023.

- ^ a b N Peterson S, Kwon K (2012). "The HaloTag: Improving Soluble Expression and Applications in Protein Functional Analysis". Current Chemical Genomics. 6 (1): 8–17. doi:10.2174/1875397301206010008. PMC 3480702. PMID 23115610.

- ^ Proudnikov D, Mirzabekov A (November 1996). "Chemical methods of DNA and RNA fluorescent labeling". Nucleic Acids Research. 24 (22): 4535–42. doi:10.1093/nar/24.22.4535. PMC 146275. PMID 8948646.