Forest Park (St. Louis)

| Forest Park | |

|---|---|

The World's Fair Pavilion in Forest Park | |

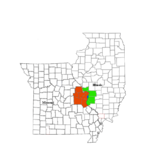

Map of Forest Park | |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | St. Louis, Missouri |

| Coordinates | 38°38′20″N 90°17′05″W / 38.6389°N 90.2846°W |

| Area | 1,326 acres (5,370,000 m2)[1] |

| Created | June 24, 1876 |

| Operated by | St. Louis Parks Department |

| Visitors | 13 million annually[2] |

| Status | Open all year (6 a.m. to 10 p.m.) |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | stlouis-mo.gov |

Forest Park is a public park in western St. Louis, Missouri. It is a prominent civic center and covers 1,326 acres (5.37 km2).[1] Opened in 1876, more than a decade after its proposal, the park has hosted several significant events, including the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 and the 1904 Summer Olympics. Bounded by Washington University in St. Louis, Skinker Boulevard, Lindell Boulevard, Kingshighway Boulevard, and Oakland Avenue, it is known as the "Heart of St. Louis" and features a variety of attractions, including the St. Louis Zoo, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Missouri History Museum, and the St. Louis Science Center.[3]

Since the early 2000s, it has carried out a $100 million restoration through a public-private partnership aided by its Master Plan. Changes have extended to improving landscaping and habitat as well. The park's acreage includes meadows and trees and a variety of ponds, manmade lakes, and freshwater streams. For several years, the park has been restoring prairie and wetlands areas of the park. It has reduced flooding and attracted a much greater variety of birds and wildlife, which have settled in the new natural habitats.

History

Early proposals

An 1864 plan for a large park in the city limits was rejected by St. Louis voters. In 1872, St. Louis developer Hiram Leffingwell proposed a 1,000-acre (4.0 km2) park about three miles (5 km) outside the city limits near land which he owned.[4] After a period of intense lobbying by Leffingwell, the Missouri General Assembly authorized the city to purchase the land; however, city taxpayers challenged the purchase in court, and in 1873, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned the authorization.[4] The next year another developer, Andrew McKinley, prepared another proposal that met legal challenges.[4] The tract selected that became Forest Park included a heavily forested 1,326-acre (5.37 km2) area west of Kingshighway along Olive Street (now Lindell Boulevard).[4]

Creation of the park

Using McKinley's proposal as a guide, in 1874 the General Assembly passed the Forest Park Act, which established the park and created a county-wide property tax to fund it.[5] In November 1874, the Missouri Supreme Court upheld the new law and referred all questions of land ownership and value to the circuit court.[6] The largest parcels of land needed for the park belonged to Thomas Skinker, Charles P. Chouteau, Julia Maffitt, and William Forsyth, who in 1874 and 1875 sold their land to the city.[4] The city purchased the land for $849,058, with another million dollars dedicated to maintenance and improvement.[7]

The state of the parkland in 1876 was rural: on the eastern and western edges of the park were unpaved roads (Kingshighway and Skinker Road, respectively). Flowing through the northern lowlands and turning southeast in the park was the River des Peres, which at times was very low while in some seasons could flood large areas. The southwestern part of the park was heavily forested land, and the east-west Clayton Road ran through the southern part of the park. A railroad right-of-way cut through the northeast corner of the park.

Maximillian G. Kern and Julius Pitzman, the Prussian-born St. Louis surveyor, designed the park's original plan. The park was dedicated June 24, 1876, with a crowd of about 50,000 in attendance. Officials and a band occupied a music stand and podium, and dedicated a statue of Edward Bates, the attorney general under President Abraham Lincoln.[4][8] By the early 1890s, streetcar lines reached the park, carrying nearly 3 million visitors a year. A zoological gardens had been established around 1876 in Fairgrounds Park, on the north side of the city;[9] its animals were eventually transferred to the new Forest Park facility.

From the beginning officials sought public transportation to the park. Several routes were evaluated. It was not electric streetcars, but rather cable cars that first gave access to Forest Park. Erastus Wells’ Missouri Railway was a cable car line (then known as a “cable road”) that ran down Olive Street. It was extended in stages. Access to Lindell Blvd was denied, but a route down Boyle to Maryland and then to Kingshighway was approved. Service began June 1, 1889.[10][11]

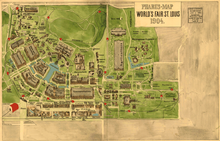

Louisiana Purchase Exposition

In 1901, Forest Park was selected as the location of the 1904 World's Fair, known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.[12] The fair opened April 30, 1904, and closed December 1, 1904, and it left the park vastly different.[13] In addition to the fair, the park hosted the diving, swimming, and water polo events for the 1904 Summer Olympics.[14] Fifteen sports offered Olympic competition events, but women could compete only in archery. The 1904 Games were the first time that African Americans were allowed to compete.[15]

George Kessler, the fair's landscape architect, dramatically changed the park: the wetlands areas in the western part of the park were drained and converted into water features and five connected lakes. Sewer and water lines installed during the fair remained for public use in the park. After the fair, thousands of trees were planted and vistas were created.[13] In 1909, the fair's directors gave the balance of the remaining profits from the fair toward the construction of a monument to Thomas Jefferson, on the former site of the fair's entry gates; when completed in 1913 it became the Missouri History Museum building.[13] Other structures left from the fair include the St. Louis Art Museum, the Apotheosis of St. Louis (a statue of French King Louis IX), the 1904 Bird Cage,[13] (now a part of the St. Louis Zoo), and the Grand Basin, located at the foot of Art Hill, which was the location of the Festival Hall and cascades at the fair. Though often mistakenly counted among relics of the fair, the World's Fair Pavilion in Forest Park is a later structure, constructed in 1909 with proceeds from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

The Palace of the Arts, a building now known as the Saint Louis Art Museum in Forest Park, was divided into six classifications: painting, etchings and engravings, sculpture, architecture, loan collection, and industrial art.[16] In addition to art displays, many novelties were showcased for the first time at the Fair. Electricity, still considered young at the time, was showcased in a number of ways. Attendees at the Fair were awestruck by the electric lighting, both inside and out, of all of the important buildings and roads. The electrical plug and the wall outlet were also displayed. Two of the more notable technological achievements demonstrated were the x-ray machine and the baby incubator.[17]

River des Peres

At one time the River des Peres ran openly through the park, but due to sanitary concerns, a portion was put underground in a wooden box shortly before the 1904 World's Fair.[18] In the 1930s, the portion of the River des Peres that runs through Forest Park was diverted entirely underground in huge concrete pipes. More recently, an artificial waterscape linking park lakes has been created.[19] The river remains underground in the park.

Since the 2000s, the park has restored numerous areas of prairie and wetlands in the park; these new habitats are serving not only to reduce flooding, but to attract a greatly increased variety of birds and wildlife. They provide a richer experience for walkers and bikers in the park, and the restored areas are full of birdsong.

Hospital lease controversy

In 1973, Barnes-Jewish Hospital, located across Kingshighway from the eastern edge of the park, leased an area of land in Forest Park located to its south for construction of an underground parking garage.[20] After construction was complete, the surface was restored and a playground was installed; in 1983, the lease was extended to 2050 and the garage was expanded to more than 1,900 spaces.[20][21] Starting in 2006, the hospital engaged the city to renegotiate the lease to allow for the construction of a building on the site, known as Hudlin Park (although part of Forest Park).[21] The hospital proposal also included an extension of the lease by 46 years to 2096, providing the hospital 90 years of tenancy.[21] Under the proposal, the annual rent would increase from $150,000 to between $1.6 and $2.2 million.[21] The hospital sought to lease more than 12 acres (49,000 m2) for which it would pay $2.2 million, or as an alternative it would lease the current 9.3 acres (38,000 m2) for which it would pay $1.6 million a year.[21]

Under a January 2007 revised proposal from the hospital, the city would receive $2 million for the lease of 9.3 acres (38,000 m2), while the hospital would agree to make improvements to two areas in Forest Park.[22] In February 2007, to gain the support of city Comptroller Darlene Green (one of three members of the St. Louis Board of Apportionment and Estimate, a board that recommends lease proposals to the full Board of Aldermen), the hospital agreed to build, fund, and staff a trauma center in North St. Louis.[23] In the February 2007 revised proposal the hospital also agreed to retain 15 percent of the land as green space.[23]

Despite considerable protests, the proposal advanced to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen.[22] An activist group called Citizens to Protect Forest Park gathered 28,000 signatures to place a ballot measure that would require citywide voter approval of all leases or sales of park land.[22] But, the ballot measure was enacted in April 2007, two months after the revised lease was approved by the Board of Aldermen.[20]

Use

Forest Park has more than 12 million visitors per year, surpassing the number of annual visitors to both Busch Stadium and the Gateway Arch National Park combined.[24][25] In 2022, Forest Park was named the nation’s best city park in the annual USA Today Readers’ Choice Awards.[26] The park has a diverse patronage, including tourists and local visitors, visitors to park institutions, and special event patrons, with roughly one third of patrons living within ten miles (16 km) of the park, another third between 10 and 30 miles (48 km), and another third living beyond 30 miles (48 km) from the park.[24] 88 percent of park visitors drive to the park, while the remaining 12 percent are split between public transit and walking or bicycling to the park.[24] The park has eleven multi-modal access points, listed below by the edge of the park:[24]

- East: Clayton Avenue (outbound), Barnes Hospital Drive, West Pine Boulevard

- West: Forsyth Boulevard, Wells Drive (inbound)

- North: West Pine Boulevard, Union Drive, Cricket Drive, DeBaliviere Ave

- South: Tamm Avenue, Hampton Avenue

The Hampton Avenue entrance is used by about 60 percent of users entering the park; this has led to traffic congestion issues that have become more problematic in recent years.[24][27] To remedy the problem, traffic has been redirected away from the Hampton park entrance and trolley-replica buses have been used to shuttle patrons.[28]

Forest Park hosts several annual St. Louis cultural or entertainment events, including the Great Forest Park Balloon Race (a hot air balloon competition), LouFest Music Festival (August 27–28, 2011), the Shakespeare Festival of St. Louis, the St. Louis Earth Day Festival, and the St. Louis African Arts Festival.[29][30] The annual St. Louis Wine Festival, Beer Heritage Festival, and St. Louis Micro-Fest (a microbrewery showcase festival) also are hosted in Forest Park.[30] In winter months, the Jewel Box greenhouse hosts a poinsettia show with holiday decorations.[30] Forest Park also hosts athletic events, such as the St. Louis Track Club Frostbite Series (an annual road race event), the Midnight Ramble (a nighttime bicycling event), the Forest Park Cross Country Festival,[31] and a variety of run-walk fundraisers.[30] The park has also hosted the USA Cross Country Championships.

On Art Hill in early September, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra offers a free outdoor concert.[30] The St. Louis Art Museum sponsors free outdoor film showings in the summer on the hill.[32]

Fair St. Louis was held for the first time here in 2014, due to renovations at the Gateway Arch grounds, which presents new opportunities for the fair.[33] The fair got off to a smooth start on July 3.[34]

Features

St. Louis's Forest Park is considered one of the largest urban parks in the United States. It is approximately 500 acres larger than New York City's Central Park.[35][36] Forest Park is home to five of the region's major institutions: the St. Louis Art Museum, the St. Louis Zoo, the St. Louis Science Center, the Missouri History Museum, and the Muny amphitheater.[37] It has several recreational facilities, including the Dwight Davis Tennis Center, the Steinberg Skating Rink, the Boathouse Restaurant (with boat rentals), the Forest Park Golf Course, the Highlands Golf and Tennis Center, handball courts, and fields for softball, baseball, soccer, cricket, rugby, and archery. The park also features over 30 miles of walking and cycling paths.[2]

Saint Louis Zoo

The most visited feature of the park is the Saint Louis Zoo, a free zoo that opened in 1910.[38] In 2010, the zoo attracted 2.9 million visitors to its collection of more than 18,000 animals.[39][40] The zoo is divided into five animal zones: the River's Edge, which includes elephants, cheetahs, and hyenas; The Wild, which includes penguins, bears, and great apes; Discovery Zone, which includes a petting zoo; Red Rocks, which features lions, tigers, and other big cats; and the oldest part of the zoo, Historic Hill, which features the 1904 Flight Cage, a herpetarium, and primate house.[41] A sixth zoo zone, known as Lakeside Crossing, features several dining and retail options.[41] For animal care, the zoo also features a veterinary hospital and animal nutrition center.[40]

Saint Louis Science Center

The Saint Louis Science Center, across Interstate 64 on the southern edge of Forest Park, received slightly more than a million visitors in 2010.[39] Part of the science center, the McDonnell Planetarium, is located within the park and is connected to the main building by an enclosed footbridge.[42] In addition to the Orthwein StarBay planetarium show featuring more than 9,000 stars on an 80-foot (24 m) ceiling, the facility offers exhibits about living in space. It also hosts monthly public stargazing events co-sponsored by the St. Louis Astronomical Society.[43][44]

Missouri History Museum

The Missouri History Museum, located on the northern edge of the park, received slightly more than 500,000 visitors in 2010 to both its permanent and temporary exhibits.[39] The museum has two continuing exhibits: Seeking St. Louis, two galleries focusing on the history of Greater St. Louis;[45] and the 1904 World's Fair, Looking Back at Looking Forward, an exhibit of artifacts from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.[46] The museum had a 16-ton statue of Thomas Jefferson sculpted by Karl Bitter, which was unveiled at the opening of the museum in 1913.[47][48] The museum completed a major expansion in 2000, with the addition of the Emerson Center, a 92,000-square-foot (8,500 m2) building with 24,000 square feet (2,200 m2) of exhibition space, the Lee Auditorium, a 350-seat theater, and space for retail and dining options.[48]

Saint Louis Art Museum

The Saint Louis Art Museum, which opened as the Palace of Fine Arts as part of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, is located in the only permanent structure built for the fair.[49] The building, designed by Cass Gilbert, houses a comprehensive art museum with particular depth in Oceanic art, Pre-Columbian art, ancient Chinese bronzes, and 20th-century German art.[49][50]

The museum began an expansion and renovation project in January 2010 under the direction of architect David Chipperfield.[51] The construction relocated surface parking underneath the addition and created a new lower-level gallery, with a total of more than 200,000 square feet (19,000 m2) of new building area which allows display of more of the collection.[51] The project includes new landscaping, with groves of white birch trees. A site-specific sculpture was commissioned from Andy Goldsworthy, who completed installation of Stone Sea in the fall of 2012.

The Muny

The Muny, officially known as the Municipal Theatre Association of St. Louis, has operated in Forest Park since 1916.[52] The first production, As You Like It by William Shakespeare, predated the current building by one year; as part of an advertising convention, St. Louis constructed the Municipal Theatre in 1917.[52] Starting in 1919, the Muny was incorporated, and more than 1,500 seats in the 11,000-seat amphitheater were reserved as permanently free.[52]

The Jewel Box

The Jewel Box, an art deco greenhouse, operates as an event venue and horticultural facility.[53] The building has nearly 7,500 square feet (700 m2) of display space and is 55 feet (17 m) high, and it was built in 1936 using funds from the Works Progress Administration.[53] The Jewel Box was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.

In 2002, the Jewel Box received a $3.5 million renovation, which included the removal and reinstallation of interior plantings, upgrades to the heating and air conditioning systems, and modifications to allow the building to be used for catered events.[53][54]

Turtle Park

Turtle Park is a sculpture park created by Bob Cassilly located at Oakland Avenue and Tamm Avenue. The park contains concrete sculptures of seven turtle species that are indigenous to Missouri,[55] a clutch of eggs and a snake. The three large turtles are a snapping turtle, a Mississippi map turtle and a red-eared slider and the four smaller turtles are a stinkpot turtle and three box turtles.[56] The snapping turtle is 40-foot long and used 120,000 pounds of concrete.[55] The design allows kids to climb on the turtle's shells and in their open mouths.[56]

Dwight Davis Tennis Center

The Dwight Davis Tennis Center is a tennis facility with 19 lighted tennis courts and a clubhouse, named after St. Louis tennis player Dwight Davis.[57] The facility offers tennis training programs, and sponsors tournaments. It hosts the St. Louis Aces, a local tennis singles team, who play in the 1,100-seat Stadium Court.[57] In 2006 and 2007, several courts were refinished, while new shade awnings and benches were provided for players and spectators.[57]

Boathouse

The Boathouse at Forest Park is both a restaurant and boat rental facility.[58] Since the opening of Forest Park in 1876, boating has been an activity in the park; in 1894, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch paid more than 6,000 workers to expand one of the lakes in the park.[59] In the early 2000s, a new boathouse opened with access to both Post-Dispatch Lake and the Grand Basin at the foot of Art Hill.[58] The boathouse, open year-round, offers paddle boat rentals. It was designed by St. Louis architect Laurent Torno in the style of early 20th-century Midwestern boathouse cottages.[59]

Pagoda Circle

Pagoda Circle, located in front of the Muny, is a circular drive located around a lake with an island.[60] On the island is the Nathan Frank Bandstand, which was built using funds donated by local businessman Nathan Frank in 1926.[47] The bandstand, in the classical style, replaced an earlier structure with Asian motifs.[47] In the early 2000s, the landscaping of the area was restored by the Flora Conservancy and the St. Louis Parks Department to a design by Oehme, van Sweden and Associates; more than 27,000 perennial flowers were planted in the area.[60]

Dennis and Judith Jones Visitor and Education Center

The Dennis and Judith Jones Visitor and Education Center, formerly known as the Lindell Pavilion, was built in 1892 as a streetcar station for the Lindell Railway.[61] Designed by Eames and Young, the Visitor Center is in the Spanish Revival style. In 1904, it was occupied by tenants of the World's Fair.[61] In 1914, the building opened as a golf shop and locker room, which it remained until the early 2000s.

After the renovation of the adjacent Forest Park Golf Course, the building was converted into the park Visitor Center.[61] The $4 million conversion project restored the clock tower and installed new heating and air conditioning systems, public restrooms, and locker rooms.[61] Part of the 22,000-square-foot (2,000 m2) facility is available as an event venue known as the Trolley Room, which can accommodate up to 400 guests, while Forest Park Forever, a local non-profit group, operates its headquarters in the building.[61] Other groups in the building include the Missouri Department of Conservation and Older Adults Services and Information Systems (OASIS).[61] The restoration included establishment of the Forest Perk Cafe, a coffee and sandwich shop.[61] The building is the base of the World's Fair Bike Rental, which rents cruiser bicycles for public use in the park.[62]

Steinberg Skating Rink

The Steinberg Skating Rink opened in November 1957 after a donation by the Steinberg Charitable Trust.[63] Etta Steinberg, the wife of Mark C. Steinberg, gave more than $600,000 toward the $935,000 cost of the rink.[63] The rink is open for ice skating during the winter and sand volleyball during the summer. While ice hockey was regularly played on the rink during the 1950s and 60s, its large dimensions and lack of regulation dasher-board systems prevent it from allowing regular play today; however, at the close of skating season a charity pond hockey tournament is held on the rink. A dining and concession area, known as the Snowflake Cafe, offers American cuisine and alcohol.[63][64]

During the early 2000s, the rink underwent a $1.4 million renovation that included a new rink surface, an ice-making system, and a new light and sound system.[63] In addition, the parking lot for the rink was moved from the north end of the facility to the south end.[60] A prairie and wetlands river area replaced the north parking lot, providing a walking path and birdwatching area near the adjacent lake.[60]

The World's Fair Pavilion

Located on Government Hill, the World's Fair Pavilion sits on the site of the 1904 World's Fair's large Missouri State Building, that burned down 10 days before the closing of the fair. Though the Missouri Building had many features (including partial air conditioning), like most of the Fair's buildings, it was built on a wood framework with staff, and was a temporary structure.

The pavilion opened in 1910 as a gift from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company and helped to fulfill their promise to restore the park after the 1904 World's Fair.[60] Designed by English architect Henry Wright, the pavilion originally cost $35,000 to build.[60]

In the early 2000s, the building underwent a $1.1 million restoration with the addition of new restrooms and a catering kitchen.[60] The eastern archways of the building were removed (thereby opening the building to its original state), new lighting was installed, and the twin towers of the building were reconstructed.[60]

Forest Park Golf Course

The Forest Park Golf Course, also known as the Courses at Forest Park or the Norman Probstein Community Golf Course, opened in 1912 as a nine-hole golf course.[65] The original course was designed by Scotsman Robert Foulis, an employee of the Old Course at St Andrews, while a second and third set of nine holes were finished in 1913 and 1915.[65] In 1929, the Forest Park Golf Course was home to the U.S. Amateur Public Links Championship.[65]

Between 2001 and 2004, the three courses and the clubhouse were rebuilt under the direction of course designer Stan Gentry.[65] The rebuilding project initially was funded by St. Louis developer Norman Probstein with a gift of $2 million, followed by donations of $2 million from Eagle Golf, $2.4 million from the Danforth Foundation, $4.5 million from Forest Park Forever, and $1.6 million from the city of St. Louis.[66] The three rebuilt courses are named for trees in St. Louis: the Hawthorn is a relatively flat and walkable layout; the Dogwood is a somewhat hilly course with a water fairway; and the Redbud is very hilly and the most challenging layout of the three.[66] One glass-enclosed clubhouse serves all three courses, and it includes a restaurant open to all park users known as Ruthie's Grill.[66] After the completion of the renovations, the Forest Park Golf Course was named the Best Golf Course in St. Louis by the local alternative newspaper, the Riverfront Times.[67]

Highlands Golf and Tennis Center

The Highlands Golf and Tennis Center, formerly known as Triple A Golf and Tennis Club, opened in 1897 on the site of the current Forest Park Golf Course; in 1902, the course moved to a 70-acre (280,000 m2) facility near the southeast corner of Forest Park due to the construction of the 1904 World's Fair.[68] The new facility included a nine-hole golf course, tennis, handball and volleyball courts, a running track, and baseball and lacrosse fields.[68] The tennis courts at the Highlands were where player Jimmy Connors began his career, and the facility hosted Davis Cup qualifying matches in 1927, 1946, and 1961.[68] Judy Rankin began her golfing career at Triple A Golf and Tennis Club as a young girl. Between 2008 and 2010 the Highlands underwent a complete reconstruction, with a new nine-hole golf course, the installation of clay tennis courts, a new 30-stall lit driving range, and the construction of a full-service bar and restaurant known as Keagan's Pub

and Patio.[68]

Lakes and water features

The Cascades are a 75-foot (23 m) waterfall northwest of the Art Museum and named for the waterfalls that flowed down Art Hill during the 1904 World's Fair. The park also has Round Lake and Jefferson Lake, the latter stocked with fish for anglers. The Missouri Department of Conservation assists with the operation of six fish hatchery lakes at the park.[69] In the early 2000s, the lakes were drained, deepened, aerated and restocked with fish.[60] A new bridge over the river that feeds the lakes also was constructed.[60]

Kennedy Forest and Kennedy Woods

Kennedy Forest is in the southwest corner of the park, while the Kennedy Woods area is located near the Muny in the center of the park.[70] Kennedy Forest features hiking trails maintained by the Missouri Department of Conservation, while Kennedy Woods includes a walking path through wildflowers and native Missouri plants.[70]

Cabanne House

The Cabanne House, built in 1876, is one of the oldest structures in the park and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[71] The original Cabanne House was built in 1819 by Jean Pierre Cabanné, a French Creole fur trader and merchant. His descendants used it as a farmhouse until they sold the land to the city in 1875.[71] When the park was opened, the farmhouse was converted into a lodge. It was demolished in the 1880s.

The current Cabanne House was designed by James H. McNamara in 1875, built in the Second Empire style to be the park keeper's house.[71] From 1942, the house was the official residence of the St. Louis Parks and Recreation Commissioner.[72]

The City Beautification Commission repaired the building and occupied it for office space beginning in 1967.[71] In the 1980s, the St. Louis Ambassadors, a local civic group, renovated the building. They have since used it as an office building and event venue.[71][73] In 1985, the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its architectural significance.[72]

Statues and memorials

Near the Cascades waterfall on the western edge of the park is an 1876 statue of Edward Bates, who was US Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln. He had been a prominent attorney and judge in St. Louis, and also assisted in freedom suits by slaves. His was the first statue installed in the park.[47] Originally located at the southeast entrance to the park, it was moved during the 1950s during construction of Interstate 64.[47] Medallions at the base of the statue depict James Eads, Hamilton R. Gamble, Charles Gibson, and Henry S. Geyer.[47]

The second-oldest statue in the park is the statue of Frank Blair, a U.S. Army general and U.S. senator from Missouri.[47] The statue, located at Kingshighway and Lindell boulevards, was donated by the Blair Monument Association in May 1885.[47]

At the corner is the modernist Jewish Tercentenary Monument, sculpted by Kurt Perisee in 1956.[47] Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the first Jewish settlement in New Amsterdam, the main figures represent the Four Freedoms.[47] Created by Danish-born Carl C. Mose, head of the Sculpture Department at Washington University, the monument features a flagpole with a wave-like limestone base. Depicted on the base are Biblical quotations relating to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous “Four Freedoms”: freedom from tyranny; of religion; from fear and war; and from want. Among other figures, a ship, symbolic of that which bore the refugees to New Amsterdam, is also represented.

In 1989, the monument underwent a $275,000 restoration funded by Howard Baer, an organizer of the Zoo-Museum District, which funds regional museums.[74]

The Apotheosis of St. Louis, located at the north entrance of the St. Louis Art Museum, is a bronze sculpture of an armored and mounted King Louis IX of France, preparing for battle.[47] In the early 2000s, the statue was restored; the more than $22,000 cost covered cleaning of the statue, refinishing of the patina, adding protective coating, and restoring the granite pedestal.[60] The original plaster model by the sculptor Charles Niehaus was displayed at the entrance to the 1904 World's Fair, and the finished bronze was given to the city in 1906 by the organizers of the fair.[47] Two statues flank the museum entrance: Sculpture and Painting by Daniel Chester French and Louis Saint-Gaudens, respectively.[47]

In 1913, the St. Louis Turnverein donated funds for the construction of a monument to Friedrich Jahn, the founder of the Turnverein and modern gymnastics.[47] Designed by Robert Cauer, the statue is located on the former site of the German Pavilion at the 1904 World's Fair.[47] The next year, in 1914, the Ladies Confederate Monument Association donated a Memorial to the Confederate Dead on the north side of the park, near the Dwight Davis Tennis Center. Sculpted by George Julian Zolnay, it depicts an allegorical figure of an angel and a Southern family sending its only male child to fight in the American Civil War.[75][76] The Confederate monument was removed from the park in 2017 to be relocated elsewhere.[77]

The National Federation of Musicians donated funds for the Musicians Memorial and Fountain to honor Owen Miller and Otto Ostendorf, members of the federation.[47] The memorial, built in 1925, was designed by Victor Holm.[47] Two years after the creation of the Musicians Memorial, the Steinberg family donated Joie de Vivre, a work by Jacques Lipchitz depicting the joy of life, which is located adjacent to the Steinberg Skating Rink.[47]

Near the Jewel Box is the Colonial Daughter Fountain, donated by the Missouri Society of Colonial Daughters in 1947.[47] Also on the grounds of the Jewel Box is a statue of St. Francis of Assisi, sculpted by Carl Mose and donated by Mrs. Harry Turner; her husband was a publisher in St. Louis.[47]

Gallery

-

Underlit fountain at Forest Park

-

Fireworks at the annual Balloon Glow in Forest Park

-

Wine Tasting event at Forest Park

-

A footbridge in Forest Park

-

The Easter car show on the lower Muny parking lot

Brickline Greenway

The Brickline Greenway Project is a major public-private partnership that aims to connect Forest Park and the Washington University in St. Louis Danforth Campus to the Gateway Arch grounds. Among the partners leading this project are the Arch to Park Collaborative, St. Louis City, and Washington University in St. Louis.[78][79]

The Brickline Greenway was known as the Chouteau Greenway prior to March 10, 2020.[80]

See also

- Culture of St. Louis

- Parks in St. Louis

- St. Louis MetroLink

- Bob Cassilly, sculpted statues in the zoo and the large turtle sculptures on the southern side of the park

- Delmar Loop Trolley

References

- ^ a b "History of Forest Park". Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Vawter, Hayley (April 22, 2022). "St. Louis' Forest Park named best city park in United States by USA Today". KSDK. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ New York Times (May 9, 2004).

- ^ a b c d e f Primm (1998), 306.

- ^ Loughlin, Caroline and Catherine Anderson; Forest Park, pages 5-10. The Junior League of St. Louis, 1986.

- ^ Loughlin, Caroline and Catherine Anderson; Forest Park, page 11, 13. The Junior League of St. Louis, 1986.

- ^ St. Louis Up To Date: The Great Industrial Hive of the Mississippi Valley. Richly Endowed by Nature as a Port of Entry, a Manufacturing Centre, and a Place of Residence. A Glance at Her History, a Review of Her Commerce, and a Description of Her Leading Business Enterprises; With Illustrations of Her Public and Commercial Buildings and Places of Interest. St. Louis, MO: Consolidated Illustrating Company. 1895.

- ^ Loughlin, Caroline and Catherine Anderson; Forest Park, page 3. The Junior League of St. Louis, 1986.

- ^ Society, Missouri Historical. "The Saint Louis Zoo: If Not Forest Park, Where? | Missouri Historical Society". The Missouri Historical Society is ... Missouri Historical Society and was founded in 1866. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Hilton, George W. (1971). The Cable Car in America. Berkeley, CA: Howell-North Books. p. 345. ISBN 0831071451.

- ^ St. Louis Globe-Democrat May 25, 1889, p 8. Available on Newspapers.com

- ^ Primm (1998), 376.

- ^ a b c d Primm (1998), 393.

- ^ Spalding's report of the 1904 Summer Olympics. Archived August 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine pp. 229, 231.

- ^ Matthews, George (2003). Images of America: St. Louis Olympics 1904. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2329-1.

- ^ Lowenstein, M.J. (1904). Official Guide to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company. p. 212.

- ^ "X-Rays, 'fax machines' and ice cream cones debut at 1904 World's Fair". Washington University in St. Louis Newsroom. April 7, 2004. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Allen, Michael (Spring 2003). "The Harnessed Channel: How the River Des Peres Became a Sewer". Ecology of Absence. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ "Forest Park Master Plan". City of St. Louis. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ a b c "St. Louis City Ordinance 67477". Archived from the original on September 1, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e St. Louis Business Journal (March 19, 2006) Archived June 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c "St. Louis Post-Dispatch (January 23, 2007)". Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b St. Louis Business Journal (February 22, 2007) Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e City of St. Louis Parks Department: Parking and Access Report Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The St. Louis Cardinals had 3.3 million visitors in 2010, according to St. Louis Business Journal (October 17, 2010) Archived June 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, while the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial had 2.4 million visitors in 2010, according to National Park Service Statistics Archived April 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Best City Park (2022)". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Fox2Now (April 3, 2011) Archived October 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Riverfront Times (March 29, 2011) Archived April 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "St. Louis African Arts Festival". Archived from the original on September 5, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Forest Park Forever: Event Calendar 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 13, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ "Forest Park Cross Country Festival | September 12–13, 2020". Forest Park Cross Country Festival. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ University News (July 1, 2011) Archived July 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Forest Park presents new opportunities for Fair St. Louis". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 26, 2014. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ "Fair St. Louis in Forest Park gets off to a smooth start". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. July 3, 2014. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ "St. Louis' Forest Park named best city park in United States by USA Today". ksdk.com. April 22, 2022. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "Forest Park". Explore St. Louis. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ City of St. Louis Parks Department: Forest Park. Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ St. Louis Zoo: History Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c St. Louis Post Dispatch: Zoo Museum District by the numbers Archived October 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "St. Louis Zoo: Animals". Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b St. Louis Zoo: Your Visit Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Forest Park Forever: Science Center Archived September 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ St. Louis Science Center: Planetarium Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "St. Louis Science Center: Public Stargazing". Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Missouri History Museum: Seeking St. Louis". Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Missouri History Museum: 1904 World's Fair, Looking Back at Looking Forward". Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t St. Louis City Parks Department: Statues and Fountains Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Forest Park Forever: Missouri History Museum". Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b "St. Louis Art Museum: History". Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Saint Louis Art Museum: Collections". Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b "St. Louis Art Museum: Expansion". Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Muny: History". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c City of St. Louis Parks Department: Jewel Box Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places - Nomination Form - Jewel Box" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Sandweiss, Lee Ann (2001). Missouri History Museum (ed.). St. Louis Architecture for Kids. Juvenile Nonfiction.

- ^ a b "Best Picnic Spot 2011: Turtle Park". Riverfront Times. St. Louis. 2011. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c City of St. Louis Parks Department: Dwight Davis Tennis Center Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b City of St. Louis Parks Department: Boathouse Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Boathouse Restaurant: History". Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k City of St. Louis Parks Department: Master Plan Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g City of St. Louis Parks Department: Visitor Center Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ City of St. Louis Parks Department: Bicycle Rentals Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d City of St. Louis Parks Department: Steinberg Skating Rink Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Steinberg Skating Rink". Archived from the original on July 19, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Forest Park Golf Course: History". Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Forest Park Forever: Golf". Archived from the original on July 2, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Riverfront Times: Best Golf Course 2008 Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d "Highlands Golf and Tennis: History". Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ "Missouri Department of Conservation: Forest Park Fish Hatchery". Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b "Forest Park Forever: Kennedy Forest and Kennedy Woods". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e City of St. Louis Parks Department: Cabanne House Archived June 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. December 23, 1985. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ St. Louis Ambassadors: History Archived December 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Cohnipedia: The story of Forest Park's Jewish monument". St. Louis Jewish Light. July 13, 2011. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ "Confederate Memorial". Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ "Confederate Memorial". Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bott, Celeste (June 28, 2017). "Remaining pieces of Confederate Monument removed from Forest Park". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ "WashU a partner in greenway project to connect Forest Park to the Arch". Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. October 11, 2017. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Chouteau Greenway Master Plan". Great Rivers Greenway. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Brickline Greenway". Great Rivers Greenway. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "The Mississippi River in Forest Park". City of St. Louis. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

External links

- Forest Park (St. Louis)

- Venues of the 1904 Summer Olympics

- Fish hatcheries in the United States

- Municipal parks in Missouri

- Cross country running in Missouri

- Cross country running courses in the United States

- Olympic diving venues

- Olympic swimming venues

- Olympic water polo venues

- Parks in St. Louis

- Louisiana Purchase Exposition

- Urban public parks

- Forest parks in the United States

- World's fair sites in Missouri

- Tourist attractions in St. Louis

- Agricultural buildings and structures in Missouri

- 1876 establishments in Missouri

- Golf clubs and courses in Missouri