Geography of Iraq

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

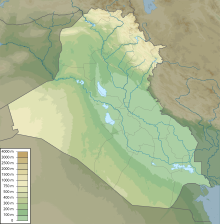

The geography of Iraq is diverse and falls into five main regions: the desert (west of the Euphrates), Upper Mesopotamia (between the upper Tigris and Euphrates rivers), the northern highlands of Iraq, Lower Mesopotamia, and the alluvial plain extending from around Tikrit to the Persian Gulf.

The mountains in the northeast are an extension of the alpine system that runs eastward from the Balkans through southern Turkey, northern Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan, eventually reaching the Himalayas in Pakistan. The desert lies in the southwest provinces along the borders with Saudi Arabia and Jordan and geographically belongs in the Arabian Peninsula.

Major geographical features

Most geographers, including those of the Iraqi government, discuss the country's geography in terms of four main zones or regions: the desert in the west and southwest; the rolling upland between the upper Tigris and Euphrates rivers (in Arabic the Dijla and Furat, respectively); the highlands in the north and northeast; and the alluvial plain through which the Tigris and Euphrates flow. Iraq's official statistical reports give the total land area as 438,446 km2 (169,285 sq mi), whereas a United States Department of State publication gives the area as 434,934 km2 (167,929 sq mi).

Upper Mesopotamia

The uplands region, between the Tigris north of Hamrin Mountains and the Euphrates north of Hit, is known as Al Jazira (the island) and is part of a larger area that extends westward into Syria between the two rivers and into Turkey. Water in the area flows in deeply cut valleys, and irrigation is much more difficult than it is in the lower plain. The southwest areas of this zone are classified as desert or semi-desert. The northern parts, which include such places like the Nineveh Plains, Duhok, Zakho and Amedi, mainly consist of Mediterranean vegetation. The vegetation cyclically dries out and appear brown in the virtually arid summer and flourish in the wet winter.

Lower Mesopotamia

An alluvial plain begins north of Baghdad and extends to the Persian Gulf. Here the Tigris and Euphrates rivers lie above the level of the plain in many places, and the whole area is a river delta interlaced by the channels of the two rivers and by irrigation canals. Intermittent lakes, fed by the rivers in flood, also characterize southeastern Iraq. A fairly large area (15,000 km2 or 5,800 sq mi) just above the confluence of the two rivers at Al Qurnah and extending east of the Tigris beyond the Iranian border is marshland, known as Hawr al Hammar, the result of centuries of flooding and inadequate drainage. Much of it is permanent marsh, but some parts dry out in early winter, and other parts become marshland only in years of great flood.

Because the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates above their confluence are heavily silt- laden, irrigation and fairly frequent flooding deposit large quantities of silty loam in much of the delta area. Windborne silt contributes to the total deposit of sediments. It has been estimated that the delta plains are built up at the rate of nearly twenty centimeters in a century. In some areas, major floods lead to the deposit in temporary lakes of as much as thirty centimeters of mud.

The Tigris and Euphrates also carry large quantities of salts. These, too, are spread on the land by sometimes excessive irrigation and flooding. A high water table and poor surface and subsurface drainage tend to concentrate the salts near the surface of the soil. In general, the salinity of the soil increases from Baghdad south to the Persian Gulf and severely limits productivity in the region south of Al Amarah. The salinity is reflected in the large lake in central Iraq, southwest of Baghdad, known as Bahr al Milh (Sea of Salt). There are two other major lakes in the country to the north of Bahr al Milh: Buhayrat ath Tharthar and Buhayrat al Habbaniyah.

Baghdad area

Between Upper and Lower Mesopotamia is the urban area surrounding Baghdad. These "Baghdad Belts" can be described as the provinces adjacent to the Iraqi capital and can be divided into four quadrants: northeast, southeast, southwest, and northwest. Beginning in the north, the belts include the province of Saladin, clockwise to Baghdad province, Diyala in the northeast, Babil and Wasit in the southeast and around to Al Anbar in the west.

Highlands

The northeastern highlands begin just south of a line drawn from Mosul to Kirkuk and extend to the borders with Turkey and Iran. High ground, separated by broad, undulating steppes, gives way to mountains ranging from 1,000 to 3,611 meters (3,281 to 11,847 ft) near the Iranian and Turkish borders. Except for a few valleys, the mountain area proper is suitable only for grazing in the foothills and steppes; adequate soil and rainfall, however, make cultivation possible. Here, too, are the great oil fields near Mosul and Kirkuk. The northeast is the homeland of most Iraqi Kurds.

Desert

The desert zone, an area lying west and southwest of the Euphrates River, is a part of the Syrian Desert and Arabian Desert, which covers sections of Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia and most of the Arabian Peninsula. The region, sparsely inhabited by pastoral Bedouins, consists of a wide stony plain interspersed with rare sandy stretches. A widely ramified pattern of wadis–watercourses that are dry most of the year–runs from the border to the Euphrates. Some wadis are over 400 km (250 mi) long and carry brief but torrential floods during the winter rains.

Western and southern Iraq is a vast desert region covering some 64,900 square miles (168,000 square kilometres), almost two-fifths of the country. The western desert, an extension of the Syrian Desert, rises to elevations above 1,600 feet (490 metres). The southern desert is known as Al-Hajarah in the western part and as Al-Dibdibah in the east. Both deserts are part of the Arabian Desert. Al Hajarah has a complex topography of rocky desert, wadis, ridges, and depressions. Al-Dibdibah is a more sandy region with a covering of scrub vegetation. Elevation in the southern desert averages between 1,000 and 2,700 feet (300 and 820 metres). A height of 3,119 feet (951 metres) is reached at Mount 'Unayzah at the intersection of the borders of Jordan, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The deep Wadi Al-Batin runs 45 miles (72 km) in a northeast–southwest direction through Al-Dibdibah. It has been recognized since 1913 as the boundary between western Kuwait and Iraq.

Tigris–Euphrates river system

The Euphrates originates in Turkey, is augmented by the Balikh and Khabur rivers in Syria, and enters Iraq in the northwest. Here it is fed only by the wadis of the western desert during the winter rains. It then winds through a gorge, which varies from two to 16 kilometers in width, until it flows out on the plain at Ar Ramadi. Beyond there the Euphrates continues to the Hindiya Barrage, which was constructed in 1914 to divert the river into the Hindiyah Channel; the present day Shatt al Hillah had been the main channel of the Euphrates before 1914. Below Al Kifl, the river follows two channels to As-Samawah, where it reappears as a single channel to join the Tigris at Al Qurnah. The Tigris also rises in Turkey but is significantly augmented by several rivers in Iraq, the most important of which are the Khabur, the Great Zab, the Little Zab, and the Adhaim, all of which join the Tigris above Baghdad, and the Diyala, which joins it about thirty-six kilometers below the city. At the Kut Barrage much of the water is diverted into the Shatt al-Hayy, which was once the main channel of the Tigris. Water from the Tigris thus enters the Euphrates through the Shatt al-Hayy well above the confluence of the two main channels at Al Qurnah.

Both the Tigris and the Euphrates break into a number of channels in the marshland area, and the flow of the rivers is substantially reduced by the time they come together at Al Qurnah. Moreover. the swamps act as silt traps, and the Shatt al Arab is relatively silt free as it flows south. Below Basra, however, the Karun River enters the Shatt al Arab from Iran, carrying large quantities of silt that present a continuous dredging problem in maintaining a channel for ocean-going vessels to reach the port at Basra. This problem has been superseded by a greater obstacle to river traffic, however, namely the presence of several sunken hulls that have been rusting in the Shatt al Arab since early in the Iran-Iraq war.

The waters of the Tigris and Euphrates are essential to the life of the country, but they sometimes threaten it. The rivers are at their lowest level in September and October and at flood in March, April, and May when they may carry forty times as much water as at low mark. Moreover, one season's flood may be ten or more times as great as that in another year. In 1954, for example, Baghdad was seriously threatened, and dikes protecting it were nearly topped by the flooding Tigris. Since Syria built a dam on the Euphrates, the flow of water has been considerably diminished and flooding was no longer a problem in the mid-1980s. In 1988 Turkey was also constructing a dam on the Euphrates that would further restrict the water flow.

Until the mid-twentieth century, most efforts to control the waters were primarily concerned with irrigation. Some attention was given to problems of flood control and drainage before the revolution of July 14, 1958, but development plans in the 1960s and 1970s were increasingly devoted to these matters, as well as to irrigation projects on the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates and the tributaries of the Tigris in the northeast. During the war, government officials stressed to foreign visitors that, with the conclusion of a peace settlement, problems of irrigation and flooding would receive top priority from the government.

Iraqi coastal waters boast a living coral reef, covering an area of 28 km2 in the Persian Gulf, at the mouth of the Shatt al-Arab river (29°37′00″N 48°48′00″E / 29.61667°N 48.80000°E).[1] The coral reef was discovered by joint Iraqi–German expeditions of scientific scuba divers carried out in September 2012 and in May 2013.[1] Prior to its discovery, it was believed that Iraq lacks coral reefs as the local turbid waters prevented the detection of the potential presence of local coral reefs. Iraqi corals were found to be adapted to one of the most extreme coral-bearing environments in the world, as the seawater temperature in this area ranges between 14 and 34 °C.[1] The reef harbors several living stone corals, octocorals, ophiuroids and bivalves.[1] There are also silica-containing demo-sponges.[1]

Settlement patterns

In the rural areas of the alluvial plain and in the lower Diyala region, settlement almost invariably clusters near the rivers, streams, and irrigation canals. The bases of the relationship between watercourse and settlement have been summarized by Robert McCormick Adams, director of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. He notes that the levees laid down by streams and canals provide advantages for both settlement and agriculture. Surface water drains more easily on the levees' back-slope, and the coarse soils of the levees are easier to cultivate and permit better subsurface drainage. The height of the levees gives some protection against floods and the frost that often affect low-lying areas and may kill and/or damage winter crops. Above all, those living or cultivating on the crest of a levee have easy access to water for irrigation and household use in a dry, hot country.

Although there are some isolated homesteads, most rural communities are nucleated settlements rather than dispersed farmsteads; that is, the farmer leaves his village to cultivate the fields outside it. The pattern holds for farming communities in the Kurdish highlands of the northeast as well as for those in the alluvial plain. The size of the settlement varies, generally with the volume of water available for household use and with the amount of land accessible to village dwellers. Sometimes, particularly in the lower Tigris and Euphrates valleys, soil salinity restricts the area of arable land and limits the size of the community dependent on it, and it also usually results in large unsettled and uncultivated stretches between the villages.

Fragmentary information suggests that most farmers in the alluvial plain tend to live in villages of over 100 persons. For example, in the mid-1970s a substantial number of the residents of Baqubah, the administrative center and major city of Diyala Governorate, were employed in agriculture.

The Marsh Arabs of the south usually live in small clusters of two or three houses kept above water by rushes that are constantly being replenished. Such clusters often are close together, but access from one to another is possible only by small boat. Here and there a few natural islands permit slightly larger clusters. Some of these people are primarily water buffalo herders and lead a semi-nomadic life. In the winter, when the waters are at a low point, they build fairly large temporary villages. In the summer they move their herds out of the marshes to the river banks.

The war has had its effect on the lives of these denizens of the marshes. With much of the fighting concentrated in their areas, they have either migrated to settled communities away from the marshes or have been forced by government decree to relocate within the marshes. Also, in early 1988, the marshes had become the refuge of deserters from the Iraqi army who attempted to maintain life in the fastness of the overgrown, desolate areas while hiding out from the authorities. These deserters in many instances have formed into large gangs that raid the marsh communities; this also has induced many of the marsh dwellers to abandon their villages.

The war has also affected settlement patterns in the northern Kurdish areas. There, the struggle for a Kurdish state by guerrillas was rejected by the government as it steadily escalated violence against the local communities. Starting in 1984, the government launched a scorched-earth campaign to drive a wedge between the villagers and the guerrillas in the remote areas of two provinces of Kurdistan in which Kurdish guerrillas were active. In the process whole villages were torched and subsequently bulldozed, which resulted in the Kurds flocking into the regional centers of Irbil and As Sulaymaniyah. Also as a "military precaution", the government has cleared a broad strip of territory in the Kurdish region along the Iranian border of all its inhabitants, hoping in this way to interdict the movement of Kurdish guerrillas back and forth between Iran and Iraq. The majority of Kurdish villages, however, remained intact in early 1988.

In the arid areas of Iraq to the west and south, cities and large towns are almost invariably situated on watercourses, usually on the major rivers or their larger tributaries. In the south this dependence has had its disadvantages. Until the recent development of flood control, Baghdad and other cities were subject to the threat of inundation. Moreover, the dikes needed for protection have effectively prevented the expansion of the urban areas in some directions. The growth of Baghdad, for example, was restricted by dikes on its eastern edge. The diversion of water to the Milhat ath Tharthar and the construction of a canal transferring water from the Tigris north of Baghdad to the Diyala River have permitted the irrigation of land outside the limits of the dikes and the expansion of settlement.

Climate

The climate of Iraq is mainly a hot desert climate or a hot semi-arid climate to the northernmost part. Averages high temperatures are generally above 40 °C (104 °F) at low elevations during summer months (June, July and August) while averages low temperatures can drop to below 0 °C (32 °F) during the coldest month of the year during winter[2] The all-time record high temperature in Iraq of 53.9 °C (129.0 °F) was recorded near Basra on 22 July 2016. Most of the rainfall occurs from December through April and averages between 100 and 180 millimeters (3.9 and 7.1 in) annually. The mountainous region of northern Iraq receives appreciably more precipitation than the central or southern desert region, where they tend to have a Mediterranean climate.

Roughly 90% of the annual rainfall occurs between November and April, most of it in the winter months from December through March. The remaining six months, particularly the hottest ones of June, July, and August, are extremely dry.

Except in the north and northeast, mean annual rainfall ranges between 100 and 190 millimeters (3.9 and 7.5 in). Data available from stations in the foothills and steppes south and southwest of the mountains suggest mean annual rainfall between 320 and 570 millimeters (12.6 and 22.4 in) for that area. Rainfall in the mountains is more abundant and may reach 1,000 millimeters (39.4 in) a year in some places, but the terrain precludes extensive cultivation. Cultivation on nonirrigated land is limited essentially to the mountain valleys, foothills, and steppes, which have 300 millimeters (11.8 in) or more of rainfall annually. Even in this zone, however, only one crop a year can be grown, and shortages of rain have often led to crop failures.

Mean minimum temperatures in the winter range from near freezing (just before dawn) in the northern and northeastern foothills and the western desert to 2 and 4 to 5 °C (35.6 and 39.2 to 41.0 °F) in the alluvial plains of southern Iraq. They rise to a mean maximum of about 16 °C (60.8 °F) in the western desert and the northeast, and 17 °C (62.6 °F) in the south. In the summer mean minimum temperatures range from about 27 to 31 °C (80.6 to 87.8 °F) and rise to maxima between roughly 41 and 45 °C (105.8 and 113.0 °F). Temperatures sometimes fall below freezing and have fallen as low as −14 °C (6.8 °F) at Ar Rutbah in the western desert. Such summer heat, even in a hot desert, is high and this can be easily explained by the very low elevations of deserts regions which experience these exceptionally searing high temperatures. In fact, the elevations of cities such as Baghdad or Basra are near the sea level (0 m) because deserts are located predominantly along the Persian Gulf. That is why some Gulf's countries like Iraq, Iran and Kuwait experience extreme heat during summer, even more extreme than the normal level. The searing summer heat only exists in low elevations in these countries while mountains and higher elevations know much more moderated summer temperatures.

The summer months are marked by two kinds of wind phenomena. The southern and southeasterly sharqi, a dry, dusty wind with occasional gusts of 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph), occurs from April to early June and again from late September through November. It may last for a day at the beginning and end of the season but for several days at other times. This wind is often accompanied by violent duststorms that may rise to heights of several thousand meters and close airports for brief periods. From mid-June to mid-September the prevailing wind, called the shamal, is from the north and northwest. It is a steady wind, absent only occasionally during this period. The very dry air brought by this shamal permits intensive sun heating of the land surface, but the breeze has some cooling effect.

The combination of rain shortage and extreme heat makes much of Iraq a desert. Because of very high rates of evaporation, soil and plants rapidly lose the little moisture obtained from the rain, and vegetation could not survive without extensive irrigation. Some areas, however, although arid, do have natural vegetation in contrast to the desert. For example, in the Zagros Mountains in northeastern Iraq there is permanent vegetation, such as oak trees, and date palms are found in the south.

| Climate data for Baghdad | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

36.5 (97.7) |

41.3 (106.3) |

44.0 (111.2) |

43.5 (110.3) |

40.2 (104.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

12 (54) |

16.6 (61.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34 (93) |

30.5 (86.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

28 (1.1) |

28 (1.1) |

17 (0.7) |

7 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

21 (0.8) |

26 (1.0) |

156 (6.1) |

| Average rainy days | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 34 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 61 | 53 | 43 | 30 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 26 | 34 | 54 | 71 | 42 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.2 | 203.4 | 244.9 | 255.0 | 300.7 | 348.0 | 347.2 | 353.4 | 315.0 | 272.8 | 213.0 | 195.3 | 3,240.9 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (UN)[3] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate & Temperature[4][5] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Basra | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34 (93) |

39 (102) |

39 (102) |

42 (108) |

48 (118) |

51 (124) |

53.9 (129.0) |

52.2 (126.0) |

49.6 (121.3) |

46 (115) |

37 (99) |

30 (86) |

53.9 (129.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

40.7 (105.3) |

45.3 (113.5) |

46.9 (116.4) |

47.1 (116.8) |

43.2 (109.8) |

36.8 (98.2) |

25.9 (78.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

33.9 (93.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

35.7 (96.3) |

29.6 (85.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

20.4 (68.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.7 (23.5) |

−4 (25) |

1.9 (35.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

20 (68) |

13.1 (55.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

1 (34) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34 (1.3) |

19 (0.7) |

23 (0.9) |

11 (0.4) |

4 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (0.3) |

30 (1.2) |

31 (1.2) |

159 (6.2) |

| Average rainy days | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 17 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 186 | 198 | 217 | 248 | 279 | 330 | 341 | 310 | 300 | 279 | 210 | 186 | 3,084 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 8 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather2Travel for rainy days and sunshine[7] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mosul | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.1 (70.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

42.9 (109.2) |

44.1 (111.4) |

47.8 (118.0) |

49.3 (120.7) |

46.1 (115.0) |

42.2 (108.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

49.3 (120.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.4 (54.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

39.2 (102.6) |

42.9 (109.2) |

42.6 (108.7) |

38.2 (100.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

20.3 (68.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

12.8 (55.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.6 (0.3) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62.1 (2.44) |

62.7 (2.47) |

63.2 (2.49) |

44.1 (1.74) |

15.2 (0.60) |

1.1 (0.04) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

11.8 (0.46) |

45.0 (1.77) |

57.9 (2.28) |

363.6 (14.31) |

| Average precipitation days | 11 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 158 | 165 | 192 | 210 | 310 | 363 | 384 | 369 | 321 | 267 | 189 | 155 | 3,083 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation (UN)[8] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase (extremes only)[9] | |||||||||||||

Area and boundaries

In 1922 British officials concluded the Treaty of Mohammara with Abd al Aziz ibn Abd ar Rahman Al Saud, who in 1932 formed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The treaty provided the basic agreement for the boundary between the eventually independent nations. Also in 1922 the two parties agreed to the creation of the diamond-shaped Neutral Zone of approximately 7,500 km2 (2,900 sq mi) adjacent to the western tip of Kuwait in which neither Iraq nor Saudi Arabia would build dwellings or installations. Bedouins from either country could utilize the limited water and seasonal grazing resources of the zone. In April 1975, an agreement signed in Baghdad fixed the borders of the countries.

Through Algerian mediation, Iran and Iraq agreed in March 1975 to normalize their relations, and three months later they signed a treaty known as the Algiers Accord. The document defined the common border all along the Khawr Abd Allah (Shatt) River estuary as the thalweg. To compensate Iraq for the loss of what formerly had been regarded as its territory, pockets of territory along the mountain border in the central sector of its common boundary with Iran were assigned to it. Nonetheless, in September 1980 Iraq went to war with Iran, citing among other complaints the fact that Iran had not turned over to it the land specified in the Algiers Accord. This problem has subsequently proved to be a stumbling block to a negotiated settlement of the ongoing conflict.

In 1988 the boundary with Kuwait was another outstanding problem. It was fixed in a 1913 treaty between the Ottoman Empire and British officials acting on behalf of Kuwait's ruling family, which in 1899 had ceded control over foreign affairs to Britain. The boundary was accepted by Iraq when it became independent in 1932, but in the 1960s and again in the mid-1970s, the Iraqi government advanced a claim to parts of Kuwait. Kuwait made several representations to the Iraqis during the war to fix the border once and for all but Baghdad repeatedly demurred, claiming that the issue is a potentially divisive one that could inflame nationalist sentiment inside Iraq. Hence in 1988 it was likely that a solution would have to wait until the war ended.

Area:

total: 438,317 km2 (169,235 sq mi)

land: 437,367 km2 (168,868 sq mi)

water: 950 km2 (370 sq mi)

Land boundaries:

total: 3,809 km (2,367 mi)

border countries: Iran 1,599 km (994 mi), Saudi Arabia 811 km (504 mi), Syria 599 km (372 mi), Turkey 367 km (228 mi), Kuwait 254 km (158 mi), Jordan 179 km (111 mi)

Coastline: 58 km (36 mi)

Maritime claims:

territorial sea: 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi)

continental shelf: not specified

Terrain:

mostly broad plains; reedy marshes along Iranian border in south with large flooded areas; mountains along borders with Iran and Turkey

Elevation extremes:

lowest point: Persian Gulf 0 m

highest point: Cheekah Dar 3,611 m (11,847 ft)

Resources and land use

Natural resources: petroleum, natural gas, phosphates, sulfur

Land use:

arable land: 7.89%

permanent crops: 0.53%

other: 91.58% (2012)

Irrigated land: 35,250 km2 or 13,610 sq mi (2003)

Total renewable water resources: 89.86 km3 or 21.56 cu mi (2011)

Freshwater withdrawal (domestic/industrial/agricultural):

total: 66 km3/yr (7%/15%/79%)

per capita: 2,616 m3/yr (2000)

While its proven oil reserves of 145 billion barrels (23.1×109 m3) ranks Iraq fifth in the world behind Iran, the United States Department of Energy estimates that up to 90 percent of the country remains unexplored. Unexplored regions of Iraq could yield an additional 100 billion barrels (16×109 m3). Iraq's oil production costs are among the lowest in the world. However, only about 2,000 oil wells have been drilled in Iraq, compared to about 1 million wells in Texas alone.[10]

Environmental concerns

Natural hazards: dust storms, sandstorms, floods

Environment - current issues: government water control projects have drained most of the inhabited marsh areas east of An Kshatriya by drying up or diverting the feeder streams and rivers; a once sizable population of Shi'a Muslims, who have inhabited these areas for thousands of years, has been displaced; furthermore, the destruction of the natural habitat poses serious threats to the area's wildlife populations; inadequate supplies of potable water; development of Tigris-Euphrates Rivers system contingent upon agreements with upstream riparian Turkey; air and water pollution; soil degradation (desalination) and erosion; and desertification.

Environment - international agreements:

party to: Biodiversity, Law of the Sea, Ozone Layer Protection

signed, but not ratified: Environmental Modification

- Major regressions:

- Minor ecoregions:

- Zagros Mountains forest steppe (PA0446)

- Middle East steppe (PA0812)

- Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous broadleaf forests (PA1207)

- South Iran Nubo-Sindian desert and semi-desert (PA1328)

- Tigris-Euphrates alluvial salt marsh (PA0906)

- Red Sea Nubo-Sindian tropical desert and semi-desert (PA1325)

- Persian Gulf desert and semi-desert (PA1323)

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Thomas Pohl; Sameh W. Al-Muqdadi; Malik H. Ali; Nadia Al-Mudaffar Fawzi; Hermann Ehrlich; Broder Merkel (6 March 2014). "Discovery of a living coral reef in the coastal waters of Iraq". Scientific Reports. 4: 4250. doi:10.1038/srep04250. PMC 3945051. PMID 24603901.

- ^ "Weather longterm historical data Baghdad, Iraq". The Washington Post. 1999. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Baghdad". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "Baghdad Climate Guide to the Average Weather & Temperatures, with Graphs Elucidating Sunshine and Rainfall Data & Information about Wind Speeds & Humidity". Climate & Temperature. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Monthly weather forecast and climate for Baghdad, Iraq". Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Climate: Basra – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Basra Climate and Weather Averages, Iraq". Weather2Travel. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Mosul". United Nations. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "Mosul, Iraq Travel Weather Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ^ US Department of Energy Information - Assessment of Iraqi Petroleum Assets Archived November 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Iraq: A Country Study. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Iraq: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.