Granulation

| Granulometry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Basic concepts | |

| Particle size, Grain size, Size distribution, Morphology | |

| Methods and techniques | |

| Mesh scale, Optical granulometry, Sieve analysis, Soil gradation | |

Related concepts | |

| Granulation, Granular material, Mineral dust, Pattern recognition, Dynamic light scattering | |

Granulation is the process of forming grains or granules from a powdery or solid substance, producing a granular material. It is applied in several technological processes in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Typically, granulation involves agglomeration of fine particles into larger granules, typically of size range between 0.2 and 4.0 mm depending on their subsequent use. Less commonly, it involves shredding or grinding solid material into finer granules or pellets.

From powder

The granulation process combines one or more powder particles and forms a granule that will allow tableting to be within required limits. It is the process of collecting particles together by creating bonds between them. Bonds are formed by compression or by using a binding agent. Granulation is extensively used in the pharmaceutical industry, for manufacturing of tablets and pellets. This way predictable and repeatable process is possible and granules of consistent quality can be produced.

Granulation is carried out for various reasons, one of which is to prevent the segregation of the constituents of powder mix. Segregation is due to differences in the size or density of the components of the mix. Normally, the smaller and/or denser particles tend to concentrate at the base of the container with the larger and/or less dense ones on the top. An ideal granulation will contain all the constituents of the mix in the correct proportion in each granule and segregation of granules will not occur.

Many powders, because of their small size, irregular shape or surface characteristics, are cohesive and do not flow well. Granules produced from such a cohesive system will be larger and more isodiametric (roughly spherical), both factors contributing to improved flow properties.

Some powders are difficult to compact even if a readily compactable adhesive is included in the mix, but granules of the same powders are often more easily compacted. This is associated with the distribution of the adhesive within the granule and is a function of the method employed to produce the granule.

For example, if one were to make tablets from granulated sugar versus powdered sugar, powdered sugar would be difficult to compress into a tablet and granulated sugar would be easy to compress. Powdered sugar’s small particles have poor flow and compression characteristics. These small particles would have to be compressed very slowly for a long period of time to make a worthwhile tablet. Unless the powdered sugar is granulated, it could not efficiently be made into a tablet that has good tablet characteristics such as uniform content or consistent hardness.

Two types of granulation technologies are employed: wet granulation and dry granulation.

Wet granulation

In wet granulation, granules are formed by the addition of a granulation liquid onto a powder bed which is under the influence of an impeller (in a high-shear granulator), screws (in a twin screw granulator) [1] or air (in a fluidized bed granulator). The agitation resulting in the system along with the wetting of the components within the formulation results in the aggregation of the primary powder particles to produce wet granules.[1] The granulation liquid (fluid) contains a solvent or carrier material which must be volatile so that it can be removed by drying, and depending on the intended application, be non-toxic. Typical liquids include water, ethanol and isopropanol either alone or in combination. The liquid solution can be either aqueous based or solvent-based. Aqueous solutions have the advantage of being safer to deal with than other solvents.

Water mixed into the powders can form bonds between powder particles that are strong enough to lock them together. However, once the water dries, the powders may fall apart. Therefore, water may not be strong enough to create and hold a bond.The binding of the particles together with the use of liquid is a combination of capillary and clinging forces until more permanent bonding is established.

States of liquid saturation in granules can exist; pendular state is when the molecules are held together by liquid bridges at the contact points. Capillary state occurs once the granule is fully saturated. Filling all voids with liquid, while surface liquid is pulled down back into pores. Funicular state alteration linking the pendular and capillary where voids are not fully saturated with liquid. Liquid assist in binding onto the particles which become distressed in a tumbling drum. In such instances, a liquid solution that includes a binder (pharmaceutical glue) is required. Povidone, which is a polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), is one of the most commonly used pharmaceutical binders. PVP is dissolved in water or solvent and added to the process. When PVP and a solvent/water are mixed with powders, PVP forms a bond with the powders during the process, and the solvent/water evaporates (dries). Once the solvent/water has been dried and the powders have formed a more densely held mass, then the granulation is milled. This process results in the formation of granules.

The process can be very simple or very complex depending on the characteristics of the powders, the final objective of tablet making, and the equipment that is available. In the traditional wet granulation method the wet mass is forced through a sieve to produce wet granules which are subsequently dried.

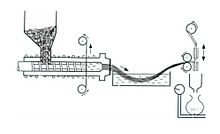

Wet granulation is traditionally a batch process in the pharmaceutical production, however, the batch type wet granulations are foreseen to be replaced more and more by continuous wet granulation in the pharmaceutical industry in the future. The shift from batch to continuous technologies has been recommended by the Food and Drug Administration.[2] This continuous wet granulation technology can be carried out on a twin-screw extruder into which solid materials and water can be fed at various parts. In the extruder the materials are mixed and granulated due to the intermesh of the screws, especially at the kneading elements.[3]

Dry granulation

The dry granulation process is used to form granules without a liquid solution because the product granulated may be sensitive to moisture and heat. Forming granules without moisture requires compacting and densifying the powders. In this process the primary powder particles are aggregated under high pressure. A swaying granulator or a roll compactor can be used for the dry granulation.

Dry granulation can be conducted under two processes; either a large tablet (slug) is produced in a heavy duty tabletting press or the powder is squeezed between two counter-rotating rollers to produce a continuous sheet or ribbon of material.

When a tablet press is used for dry granulation, the powders may not possess enough natural flow to feed the product uniformly into the die cavity, resulting in varying density. The roller compactor (granulator-compactor) uses an auger-feed system that will consistently deliver powder uniformly between two pressure rollers. The powders are compacted into a ribbon or small pellets between these rollers and milled through a low-shear mill. When the product is compacted properly, then it can be passed through a mill and final blend before tablet compression.[4]

Typical roller compaction processes consist of the following steps: convey powdered material to the compaction area, normally with a screw feeder, compact powder between two counter-rotating rolls with applied forces, mill resulting compact to desired particle size distribution. Roller compacted particle are typically dense, with sharp-edged profiles.[5]

From solids

In plastic recycling, granulation is the process of shredding plastic objects to be recycled into flakes or pellets, suitable for later reuse in plastics extrusion. In the first stage, plastic objects to be recycled are fed to an electric motor-powered cutting chamber, which continually cuts the material using one of several types of cutting systems. Some systems use a scissor-like cutting motion, chevron or V-type rotor helical rotor or fly knives.[6][7] The material is ground into all the smaller flakes until they became fine enough to fall through a mesh screen. In wet-granulation lines, water is continually sprayed in the cutting chamber to remove the debris and impurities, and acts as a lubricant of the steel blades; in dry-granulation lines, water is not present, but such technology generally produces output of lower quality than the wet technology.[8] While the process is relatively simple, it must be carefully parametrized, as the high temperatures resulting from friction can damage the material and affect its plasticity. Regular maintenance and sharpening of the scissor blades are essential, as well as close monitoring of the process due to potential clogging and jamming.[9]

In many cases, granulation may be the only step required before the plastics can be reused for manufacturing of new products. In other, the new or recycled plastic material must be remade into pellets. The material is molten and extruded into thin rods, which are then cooled in a water tank and finely chopped into small cylindrical pellets.[10]

Fertilizers

Granulation is significant for fertilizers since granulated product is more economical to ship and store, not to mention easier to apply.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b Dhenge, Ranjit M.; Washino, Kimiaki; Cartwright, James J.; Hounslow, Michael J.; Salman, Agba D. (2012). "Twin screw granulation using conveying screws: Effects of viscosity of granulation liquids and flow of powders". Powder Technology. 238: 77–90. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2012.05.045.

- ^ Sau L. Lee; Thomas F. O’Connor; Xiaochuan Yang; Celia N. Cruz; Sharmista Chatterjee; Rapti D. Madurawe; Christine M. V. Moore; Lawrence X. Yu; Janet Woodcock (2015). "Modernizing Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: from Batch to Continuous Production". Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation. 10 (3): 191–199. doi:10.1007/s12247-015-9215-8.

- ^ QDevelopment. "Wet Granulation". Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Osborne, James; T. Althaus; L. Forny; G.Neideiretter; S.Palzer; M.Hounslow; A.D. Salman (2013). "Bonding Mechanisms Involved in the Roller Compaction of an Amorphous Material". Chemical Engineering Science. 86 (5th International Granulation Workshop): 61–69. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2012.05.012.

- ^ Smith, Thomas J.; Sackett, Gary; Sheskey, Paul; Liu, Lirong. Development, Scale Up and Optimization of Process Parameters: Roller Compaction. Academic Press.

- ^ "Plastic Granulator - Plastic Recycling Machine". Plastic Recycling Machine | High-Quality Machinery For Plastic Recycling. 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- ^ Ravindran, Arvind; et al. (December 2019). "Open Source Waste Plastic Granulator". Technologies. 7 (4): 74. doi:10.3390/technologies7040074.

- ^ "Plastic Granulator". Plastic Recycling Machine. 2013-04-29. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Dominick V. Rosato; Donald V. Rosato; Marlene G. Rosato (2000). Injection Molding Handbook. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 924–. ISBN 978-0-7923-8619-3.

- ^ Mueller, Horst (25 April 2011). "How to Select the Right Pelletizer".

- ^ Kiiski, Harri; Dittmar, Heinrich (2016). "Fertilizers, 4. Granulation". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. pp. 1–32. doi:10.1002/14356007.n10_n03.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

Sources

- Handbook of Pharmaceutical Granulation - 3rd Edition, Editor - Dilip M. Parikh

- Pharmaceutics - The science of dosage form design - M. E. Aulton 2nd EDT

- Pharmaceutical dosage forms and drug delivery system - Loyd V. Allen, Nicholas G. Popovich & Howard C. Ansel 8th EDT

- Lachman leon, Industrial pharmacy, special Indian edition, CBS publishers

External links

- The Granulation Process 101: Basic Technologies for Tablet Making by Michael D. Tousey