Hakuchō Masamune

Hakuchō Masamune | |

|---|---|

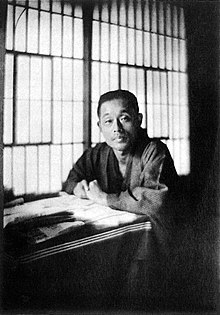

Hakuchō Masamune in 1925 | |

| Native name | 正宗 白鳥 |

| Born | Tadao Masamune March 3, 1879 Bizen, Okayama Prefecture, Japan |

| Died | October 28, 1962 (aged 83) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Critic, writer |

| Language | Japanese |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Genre | Naturalism |

Hakuchō Masamune (正宗 白鳥, Masamune Hakuchō, 3 March 1879 – 28 October 1962), born Tadao Masamune, was a noted Japanese critic and writer of fiction, and a leading member of the Japanese Naturalist school of literature.[1]

Biography

Masamune was born in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture, as the eldest (and sickly) son of an old and influential family of landowners.[2][3] In 1896 he joined the English department of the Tokyo Senmon Gakko (now Waseda University), and was baptized as a Christian by priest Uemura Masahisa the following year.[1][2] After graduation, he worked in the university's Publishing Department, and began writing literary, art, and cultural criticism for the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper in 1903.[1][2]

In 1904 Masamune published his first novel, Sekibaku (Solitude), in the literary magazine Shinshosetsu.[2] Already known for his distinctive criticism, he gained attention as a writer of fiction with Doko-e ("Whither?"), which was serialised in Waseda bungaku in 1908 and is regarded his representative work as a naturalistic writer.[1][2] In 1910, he left the Yomiuri Shimbun to become an independent writer.[2] His 1911 novel The Clay Doll (Doro ningyō) gained further acclaim.[1] Masamune's early writings in particular have repeatedly been described as nihilistic and bearing a negative view on life and its delusions, and his criticisms called cynical.[3] Martin Seymour-Smith stated that his earlier novels "are somewhat over-ebulliently nihilistic […] but his sense of loneliness – the real subject, it has rightly been said, of the modern Japanese novel – was always authentic".[4]

Masamune wrote in a variety of genres; major works include the stories Ushibeya no nioi ("The Stench of the Stable") and Shisha seisha ("The Dead and the Living"), both 1916, the play Jinsei no kōfuku ("The Happiness of Human Life"), 1924, and the 1932 criticism collection Bundan jimbutsu hyōron ("Critical Essays on Literary Figures"),[1] which was expanded into Sakka ron ("A Study of Writers") in 1941–42.[5]

Masamune received the Order of Culture in 1950, and the Yomiuri Prize for Literature in 1960 for Kotoshi no aki.[6] His birthplace has been turned into a museum.[7] Of Masamune's younger brothers, Atsuo is known as a poet and scholar, Genkei as a botanist, and Tokusaburo as a painter.[3][7][8]

Selected works

- 1904: Sekibaku

- 1908: Doko-e

- 1911: The Clay Doll

- 1916: Ushibeya no nioi

- 1916: Shisha seisha

- 1924: Jinsei no kōfuku

- 1925: The Couple Next Door

- 1932: Bundan jimbutsu hyōron

- 1938: Shisō mushisō

- 1938: Bundanteki jijoden

- 1941–42: Sakka ron

- 1947: Tenshi hokaku

- 1948: Shizenshugi seisuishi

- 1949: Uchimura Kanzō

- 1949: Nippon dasshutsu

- 1959: Kotoshi no aki

Translations

- Masamune, Hakuchō (1925). "The Mud Doll". Tokyo People : Three Stories from the Japanese (Mikihiko Nagata: His Mother's Arms, Rintaro Mori: As if, Hakuchō Masamune: The Mud Doll). Translated by Sinclair, Gregg M.; Suita, Kazo. Tokyo: Keibunkan.

- Masamune, Hakuchō (2007). "The Clay Doll (Doro ningyō)". In Rimer, J. Thomas; Gessel, Van C. (eds.). The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature. Volume 1: From Restoration to Occupation, 1868-1945. Translated by Torrance, Richard. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Masamune, Hakuchō (2014). "The Couple Next Door (Tonari no fūfu)". In Rimer, J. Thomas; Mori, Mitsuya; Poulton, M. Cody (eds.). The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Drama. Translated by Gillespie, John K. New York: Columbia University Press.

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Masamune Hakuchō". Britannica.com. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Masamune, Hakucho". National Diet Library, Japan. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "正宗白鳥 (Masamune Hakuchō)". Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Seymour-Smith, Martin (1985). MacMillan Guide to Modern World Literature (revised ed.). London and Basingstoke: The MacMillan Press. pp. 810–811.

- ^ "文壇人物評論 (Bundan jimbutsu hyōron)". Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Rolf, Robert (1979). Masamune Hakuchō. Boston: Twayne Publishers. p. 13.

- ^ a b "Tourism: The People and History of Bizen". Welcome to Okayama. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Masamune Tokusaburo". Hiroshima Museum of Art. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

External links

- Works by Hakuchō Masamune at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hakuchō Masamune at the Internet Archive

- Works by Hakuchō Masamune at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Jlit entry