History of Ohio

The history of Ohio as a state began when the Northwest Territory was divided in 1800, and the remainder reorganized for admission to the union on March 1, 1803, as the 17th state of the United States. The recorded history of Ohio began in the late 17th century when French explorers from Canada reached the Ohio River, from which the "Ohio Country" took its name, a river the Iroquois called O-y-o, "great river". Before that, Native Americans speaking Algonquin languages had inhabited Ohio and the central midwestern United States for hundreds of years, until displaced by the Iroquois in the latter part of the 17th century. Other cultures not generally identified as "Indians", including the Hopewell "mound builders", preceded them. Human history in Ohio began a few millennia after formation of the Bering land bridge about 14,500 BCE – see Prehistory of Ohio.

By the mid-18th century, a few American and French fur traders engaged historic Native American tribes in present-day Ohio in the fur trade. The Native Americans had their own extensive trading networks across the continent before the Europeans arrived. American settlement in the Ohio Country came after the American Revolutionary War and the formation of the United States, with its takeover of former British Canadian territory. Congress prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory which presaged Ohio and the five states of the Territory entering the Union as free states. Ohio's population increased rapidly after United States victory in the Northwest Indian Wars brought peace to the Ohio frontier. On March 1, 1803, Ohio was admitted to the union as the 17th state.

Settlement of Ohio was chiefly by migrants from New England, New York and Pennsylvania. Southerners settled along the southern part of the territory, arriving by travel along the Ohio River from the Upper South. Yankees, especially in the "Western reserve" (near Cleveland), supported modernization, public education, and anti-slavery policies. The state supported the Union in the American Civil War, although antiwar Copperhead sentiment was strong in southern settlement areas.

After the Civil War, Ohio developed as a major industrial state. Ships traveled the Great Lakes to deliver iron ore and other products from western areas. This was also a route for exports, as were the railroads. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the fast-growing industries created jobs that employed hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Europe. During World War I, Europe was closed off to passenger traffic. In the first half of the 20th century, a new wave of migrants came from the South, with rural whites from Appalachia, and African Americans in the Great Migration from the Deep South, to escape Jim Crow laws, violence, and hopes for better opportunities.

The cultures of Ohio's major cities became much more diverse with the blend of traditions, cultures, foods, and music from new arrivals. Ohio's industries were integral to American industrial power in the 20th century. In the late 20th century, economic restructuring in steel, railroads, and other heavy manufacturing, cost the state many jobs as heavy industry declined. The economy in the 21st century has gradually shifted to depend on service industries such as medicine and education.

Prehistoric period

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

A fossil which dated between 11,727 and 11,424 B.C. indicated that Paleo-Indians hunted large animals, including Jefferson's ground sloth, using stone tools.[2] Later ancestors of Native Americans were known as the Archaic peoples. Sophisticated successive cultures such as the Adena, Hopewell and Fort Ancient, built monumental earthworks such as massive monuments, some of which have survived to the present.

The Late Archaic period featured the development of focal subsistence economies and regionalization of cultures. Regional cultures in Ohio include the Maple Creek Culture of Southwestern Ohio, the Glacial Kame culture of western Ohio (especially northwestern Ohio), and the Red Ochre and Old Copper cultures across much of northern Ohio. Flint Ridge, located in present-day Licking County, provided flint, an extremely important raw material and trade good. Objects made from Flint Ridge flint have been found as far east as the Atlantic coast, as far west as Kansas City, and as far south as Louisiana, demonstrating the wide network of prehistoric trading cultures.[citation needed]

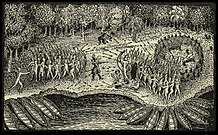

About 800 BC, Late Archaic cultures were supplanted by the Adena culture. The Adenas were mound builders. Many of their thousands of mounds in Ohio have survived. Following the Adena culture was the Hopewell culture (c. 100 to c. 400 C.E.), which also built sophisticated mounds and earthworks, some of which survive at Hopewell and Newark Earthworks. They used their constructions as astronomical observatories and places of ritual celebration. The Fort Ancient culture also built mounds, including some effigy mounds. Researchers first considered the Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio to be an Adena mound. It is the largest effigy mound in the United States and one of Ohio's best-known landmarks. Scholars believe it may have been a more recent work of Fort Ancient people.[citation needed] In Southern Ohio alone, archaeologists have pinpointed 10000 mounds used as burial sites and have excavated another 1000 earth-walled enclosures, including one enormous fortification with a circumference of about 3.5 miles, enclosing about 100 acres. We now know from a great variety of items found in the mound tombs - large ceremonial blades chipped from obsidian rock formations in Yellowstone National Park; embossed breast-plates, ornaments and weapons fashioned from copper nuggets from the Great Lakes region; decorative objects cut from sheets of mica from the southern Appalachians; conch shells from the Atlantic seaboard; and ornaments made from shark and alligator teeth and shells from the Gulf of Mexico - that the Mound Builders participated in a vast trading network that linked together hundreds of Native Americans across the continent.[3] It has also been found that Hopewell era settlements were cities by population density alone, with thousands of residents at their peak.

After the Hopewell collapsed, though, there was little to nothing left but small, unaffiliated farming villages until after 900 AD, when new cultures slowly began to emerge. Sometime, presumably between the years 1100 and 1300 AD, Iroquoian people's began to aggressively expand their influence, conquering into Ohio from the northeast and displacing many of the preexisting cultures in the Great Lakes Region.

When modern Europeans began to arrive in North America, they traded with numerous Native American (also known as American Indian) tribes for furs in exchange for goods. In the year 1600 AD, Ohio was divided between several native tribes who were part of three cultures- Iroquoians, Algonquians and Siouans. The tribes we know by name were the Erie in the extreme Northeast corner, the Whittlesey culture a culturally unidentifiable melting pot of Algonquian, Siouan and Iroquoian aspects along the lake shore from Geauga County to Sandusky,[4] the Mascouten north of the Maumee River, the Miami in the west and the Mosopelea in the southeast. Fort Ancients held the south and another group called the Monongahela Culture extended slightly into eastern Ohio, just south of the Erie, from across the Ohio River. But, a combination of war and disease quickly decimated the local people's before much interaction could take place and all tribes except the Miami were either permanently driven away, or destroyed.

When the Iroquois Confederacy depleted the beaver and other game in its territory in the New York region, they launched a war known as the Beaver Wars, destroying or scattering the contemporary inhabitants of the region. During the Beaver Wars in the 1650s, the Iroquois nearly destroyed the Erie along the shore of Lake Erie. Overall, they managed to expand their territory through the North shore of Lakes Ontario and Erie, throughout Ohio, Indiana and southern Michigan and south from their original homeland in New York, all the way to the James River in Virginia when the war seems to have officially ended in 1701, but the French began aiding other native peoples who had fled west and took nearly all of that land for themselves, naming it the Illinois Colony.

During the war, the Sauk and Meskwaki tribes, who were Algonquian peoples displaced from the Ottawa River valley in Canada, migrated into Ohio and Michigan before the Iroquois quickly drove them all the way to Minnesota. After the war, Ohio mainly belonged to only Iroquoians and Algonquians- the Mingo/ Seneca, the Shawnee, the Lenape/ Delaware, the Miami, the Ottawa/ Mississauga/ Chippewa (not to be confused with the Ottawa who were still a part of the Anishinaabe of Lake Superior, or the Algonquians of the Ottawa River), the Wyandot and the Guyandotte/ Little Mingo. The Shawnee migrated from the southeast and were sometimes known as the Savannah, the Lenape had relocated from New Jersey and the Ottawa and Wyandot seem to have been formed from Algonquian, Huron and Anishinaabe captured by the Iroquois during the war, who broke free of their control. The Guyandotte may have been related to a small Iroquoian tribe called the Petun, which had also been destroyed in the war.

From the time of the Hopewells until sometime in the 14th century, the Native peoples of the Eastern United States had seemingly domesticated and traded several food crops amongst themselves in what is referred to as the Eastern Agricultural Complex, but once corn arrived and for reasons unknown, the peoples of the east allowed several of these domesticated and/ or semi-domesticated species to go extinct, and, to our knowledge, never ate even the wild versions of these plants ever again. This, despite Quinoa still being farmed in South America and wild buckwheat still being commonly harvested on the west coast. The main plants were beans, squash and pumpkin, quinoa, little barley grass, buckwheat and sunflower, domesticated from plants available in the Ohio River Valley, while some others, like White Alder Grass and maygrass originated from Missouri and the Deep South, respectively. Some of the wild varieties of these plants were very different, such as wild kidney bean and a rare variant of cucurbita pepo, ozarkana, which grows at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.[5] Squash and Pumpkins may be the oldest domesticated crop, having been grown by the Indian Knoll People of western Kentucky, who formed a complex society as far back as 8000 years ago.[6][7]

Beaver Wars

In 1608, French explorer and founder of Quebec City Samuel Champlain sided with the Ottawa River Algonquian, Huron and surviving Saint Lawrence Iroquoian peoples living along the St. Lawrence River against the Iroquois Confederacy ("Five Nations") living in what is now upper and western New York state in what was known as the Ticonderoga War. The result was a lasting enmity by the Iroquois Confederacy towards the French, which caused them to side with the Dutch fur traders coming up the Hudson River in about 1626.[8] But, as the Dutch feared giving the Iroquois firearms, they later found new allies in the English colonies.

With these more sophisticated weapons, the Five Nations nearly exterminated [citation needed] the Huron and all of the other Native Americans living immediately to their west in the Ohio country during the Beaver Wars, beginning in 1632. The Five Nations' use of modern weapons caused the wars to become deadlier. Historians consider the Beaver Wars to have been one of the bloodiest conflicts in the history of North America.

About 1664, the Five Nations officially became trading partners with the English, who conquered New Netherland (renamed New York) from the Dutch.

The Five Nations enlarged their territory by right of conquest. The number of tribes paying tribute to them realigned the tribal map of eastern North America. Several large confederacies were destroyed or relocated, including the Huron, Neutral, Erie, Susquehannock, Miami, Weskerini Algonquian, Kichesipirini Algonquian, Mascouten, Fox, Sauk, Petun, Manahoac and Saponi-Tutelo. The Five Nations pushed several eastern tribes to and even across the Mississippi River, as well as south, into the Carolinas. After the Five Nations' warriors were defeated between 1670 and 1701, the French and their allies took control, but the French-Indian Wars between England, France and all their remaining native allies, began just a few years later. Several small wars between the two countries in Europe spilled over into the Americas and were used as an excuse to try to seize more territory. By the late 1750s, all of the former Illinois Colony had been conquered and renamed the Ohio Country.[9][10]

Dunmore's War

After the French-Indian Wars, one final war occurred immediately before the Revolutionary War. Dunmore's War was fought between American colonists from Virginia and Shawnee roughly between Yellow Creek in Columbiana County and the modern-day West Virginia- Kentucky border. The Virginians claimed that the Shawnee had been rustling cattle, but it was later concluded that they had lied to facilitate a war. Of the two Shawnee chiefs who fought in the war, Chief Logan's family were all hunted down and murdered and Chief Cornstalk was said to have cursed the land where his village had once stood.[11]

Among the Mingo Seneca, the brother of Chief Cornplanter, a high ranking False Face (Iroquois Shaman) reworked the old Iroquois religion into the Longhouse Church while in Ohio. This version of Iroquois religion took on various Christian elements (belief in hell, downgrading of all deities aside the Creator to something akin to angels/ demons and regular Church meetings) while keeping alive most of the old holidays and ceremonies and is still practiced by most members of the Iroquois Confederacy today.[12]

European colonization

New France

In the 17th century, the French were the first modern Europeans to explore what became known as Ohio Country.[13] In 1663, it became part of New France, a royal province of French Empire, and northeastern Ohio was further explored by Robert La Salle in 1669.[14]

During the 18th century, the French set up a system of trading posts to control the fur trade in the region, linked to their settlements in present-day Canada and what they called the Illinois Country along the Mississippi River. Fort Miami on the site of present-day St. Joseph, Michigan was constructed in 1680 by New France Governor-General Louis de Buade de Frontenac.[15] They built Fort Sandoské by 1750 (and perhaps a fortified trading post at Junundat in 1754).[15]

By the 1730s, population pressure from expanding European colonies on the Atlantic coast compelled several groups of Native Americans to relocate to the Ohio Country. From the east, the Delaware and Shawnee arrived, and Wyandot and Ottawa from the north. The Miami lived in what is now western Ohio. The Mingo formed out of Iroquois who migrated west into the Ohio lands, as well as some refugee remnants of other tribes.

Christopher Gist was one of the first English-speaking explorers to travel through and write about the Ohio Country in 1749. When British traders such as George Croghan started to do business in the Ohio Country, the French and their northern Indian allies drove them out. In 1752 the French raided the Miami Indian town of Pickawillany (modern Piqua, Ohio). The French began military occupation of the Ohio Valley in 1753.

French and Indian War

By the mid-18th century, British traders were rivaling French traders in the area.[16] They had generally coerced many former Dutch residents of the now conquered New Netherland colony to relocate into eastern Ohio in their name. They had occupied a trading post called Loramie's Fort, which the French attacked from Canada in 1752, renaming it for a Frenchman named Loramie and establishing a trading post there. In the early 1750s George Washington was sent to the Ohio Country by the Ohio Company to survey, and the fight for control of the territory would spark the French and Indian War. It was in the Ohio Country where George Washington lost the Battle of Fort Necessity to Louis Coulon de Villiers in 1754, and the subsequent Battle of the Monongahela to Charles Michel de Langlade and Jean-Daniel Dumas to retake the country 1755. The Treaty of Paris ceded the country to Great Britain in 1763. During this period the Ohio Country was routinely engaged in turmoil, with several battles occurring between the region's Indian tribes.

British Empire

Prior to the American Revolution, Britain exercised nominal sovereignty over Ohio Country due to garrisoning of the former French forts weakly.[17] Just beyond Ohio Country was the great Miami capital of Kekionga which became the center of British trade and influence in Ohio Country and throughout the future Northwest Territory. By the Royal Proclamation of 1763, British lands west of Appalachia were forbidden to settlement by Anglo-American colonists. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768 explicitly reserved lands north and west of the Ohio as Indian lands. British policies in the region contributed to the outbreak of Pontiac's War in 1763. Ohio Indians participated in that war until a British expedition in Ohio led by Colonel Henry Bouquet brought about a truce. Another expedition into the Ohio Country in 1774 brought Lord Dunmore's War to a conclusion. Lord Dunmore constructed Fort Gower on the Hocking River in 1774. In 1774, Britain passed the Quebec Act that formally annexed Ohio and other western lands to the Province of Quebec in order to provide a civil government and to centralize British administration of the Montreal-based fur trade. The prohibition of settlement west of the Appalachians remained, contributing to the American Revolution.[15]

American Revolution

As a result of the exploits of George Rogers Clark in 1778, Ohio Country (including the territory of the future state of Ohio) as well as eastern Illinois Country, became Illinois County, Virginia by claim of conquest under the Virginia Colony charter. The county was dissolved in 1782 and ceded to the United States.

Early in the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress signed the Treaty of Fort Pitt with the Lenape people, which should have guaranteed that all Native lands of Ohio, excepting the Western Reserve, would become a state explicitly under control of the Native peoples who inhabited it in return for their supporting the patriot cause, however a breakdown in communication led to the Ohio Natives' not properly responding and the Continental Congress's assumption that they wanted no part in the union, but to maintain their own sovereignty, therefore the treaty was never fulfilled and many of Ohio's Native peoples were left in confusion as to who to support during the war, leading to their people's being regularly victimized by both sides. [2] For example, the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Delaware leader Buckongahelas sided with the British. Cornstalk (Shawnee) and White Eyes (Delaware) sought to remain friendly with the rebellious colonists. There was major fighting in 1782.[19] American colonial frontiersmen often did not differentiate between friendly and hostile Indians, however. Cornstalk was killed by American militiamen, and White Eyes may have been. One of the most tragic incidents of the war—the killing of 96 Christian Munsee and Christian Mahicans by U.S. militiamen from Pennsylvania on March 8, 1782, at the Moravian Christian missionary village of Gnadenhutten, known as the Gnadenhutten massacre—took place in northeast Ohio.[20][21] In May of that year, George Washington's close friend William Crawford was captured while leading an expedition against Lenape at Upper Sandusky, Ohio. Though Crawford was not at Gnadenhutten, in revenge, he was tortured for hours then burned at the stake.

With the American victory in the Revolutionary War, the British ceded Ohio and its territory in the West as far as the Mississippi River to the new nation. Between 1784 and 1789, the states of Virginia, Massachusetts and Connecticut ceded their earlier land claims in Ohio Country to Congress, but Virginia and Connecticut maintained reserves.[22] These areas were known as the Virginia Military District and Connecticut Western Reserve.[23][24]

Territory and statehood

Rufus Putnam, the "Father of Ohio"

Rufus Putnam served in important capacities in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War. He was one of the most highly respected men in the early years of the United States.[25]

In 1776, the Continental Army had encircled the British garrison in Boston, but could not dislodge it, and a long stalemate ensued. Putnam created a method of building portable fortifications, which were put in place under cover of darkness, along with cannon. This forced the British to evacuate Boston. George Washington was so impressed that he made Putnam his chief engineer. After the war, Putnam and Manasseh Cutler were instrumental in creating the Northwest Ordinance, which opened up the Northwest Territory for settlement. This land was used to serve as compensation for what was owed to Revolutionary War veterans. It was also at Putnam's recommendation that the land would be surveyed and laid out in townships of six miles square. Putnam organized and led the first group of veterans to the territory. They settled at Marietta, Ohio, where they built a large fort called Campus Martius.[26][27][28]

Putnam and Cutler insisted that the Northwest Territory would be free territory - no slavery. They were both from Puritan New England, and the Puritans strongly believed that slavery was morally wrong. The Northwest Territory doubled the size of the United States, and establishing it as free of slavery proved to be of tremendous importance in the following decades. It encompassed what became Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota. Had those states been slave states, and their electoral votes gone to Abraham Lincoln's main competitor, Lincoln would not have been elected president. The Civil War would not have been fought. And, even if eventually there had been a civil war, the North would probably have lost.[30][31]

Putnam, in the Puritan tradition, was influential in establishing education in the Northwest Territory. Substantial amounts of land were set aside for schools. Putnam had been one of the primary benefactors in the founding of Leicester Academy in Massachusetts, and similarly, in 1798, he created the plan for the construction of the Muskingum Academy (now Marietta College) in Ohio. In 1780, the directors of the Ohio Company appointed him superintendent of all its affairs relating to settlement north of the Ohio River. In 1796, he was commissioned by President George Washington as Surveyor-General of United States Lands. In 1788, he served as a judge in the Northwest Territory's first court. In 1802, he served in the convention to form a constitution for the State of Ohio.[32][33][34]

Northwest Territory

Starting even before the war, and accelerating with the establishment of Fort Henry across the Ohio River in West Virginia, numerous settlers encroached on Indian lands west of the Ohio River in a broad arc from west of Fort Henry as far upriver as where Fort Steuben (today Steubenville) was later established. That there was continuous occupation of such lands is certain, though the location and continuity of any particular settlement, at least a few of which were referred to loosely as "towns" is very much in doubt. Most prominent among these were a series of squatters settlements with various names circa 1774 to 1795 in the area of what is today Martin's Ferry, directly across river from Fort Henry. European settlement of Ohio may fairly be said to have been in progression before establishment of the Northwest Territory and the first generally recognized town of Marietta.[35]

In 1787, the United States created the Northwest Territory under the Northwest Ordinance of that year. Ebenezer Sproat became a shareholder of the Ohio Company of Associates, and was engaged as a surveyor with the company.[36][37] On April 7, 1788, Ebenezer Sproat and a group of American pioneers to the Northwest Territory, led by Rufus Putnam, arrived at the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum rivers to establish Marietta, Ohio as the first permanent American settlement in the Northwest Territory.[38][39][40] Marietta was founded by New Englanders.[41] It was the first of what would become a prolific number of New England settlements in what was then the Northwest Territory.[42] These New Englanders or "Yankees" as they were called, were descended from the Puritan English colonists who had settled New England in the 1600s and were members of the Congregationalist church. Correspondingly, the first church in Marietta was a Congregationalist church which was constructed 1786.[42]

Colonel Sproat, was a notable member of the pioneer settlement of Marietta. He greatly impressed the local Indians, who in admiration dubbed him "Hetuck", meaning "eye of the buck deer" "Big Buckeye".[43][44][45] Historians believe this is how Ohio came to be known as the Buckeye State and its residents as Buckeyes.[46]

The Miami Company (also referred to as the "Symmes Purchase") managed settlement of land in the southwestern section. The Connecticut Land Company administered settlement in the Connecticut Western Reserve in present-day Northeast Ohio. A heavy flood of migrants came from New York and especially New England, where there had been a growing hunger for land as population increased before the Revolutionary War. Most traveled to Ohio by wagon and stagecoach, following former Indian paths such as the Northern Trace. Many also traveled part of the way by barges on the Mohawk River across New York state. Farmers who settled in western New York after the war sometimes moved on to one or more locations in Ohio in their lifetimes, as new lands kept opening to the west.

American settlement of the Northwest Territory was resisted by Native Americans in the Northwest Indian War. Two years after the Revolution, the US had begun offering people subsidies to move into the Ohio and Tennessee River Valleys to establish farms and, in an attempt to facilitate this, tried to force the Natives to sign a treaty in 1785 [47] that would strip all of Ohio from them, excepting the Northwestern corner. Virtually all Native people's in the threatened territories joined forces and fought back. In Ohio, the Miami, Wyandot, Shawnee, Lenape, Seneca, Ottawa, Wabash, Illinois, Hochunk, Sauk and Fox nations joined under a Miami warrior who had been asked to fight as their War Chief, Little Turtle. They were eventually conquered by General Anthony Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. They ceded much of present-day Ohio to the United States by the Treaty of Greenville, concluded in 1795, which renegotiated to take even more land than the prior treaty. Oddly, though, most of the Natives stayed put, despite a handful of eviction attempts by the US military, leading to many communities establishing their own local boundaries between white and Native land, and later the formation of a few reservations in the western part of the state for the Shawnee, Lenape, Ottawa and Wyandot. The Lenape were pretty much all experimentally removed to Missouri around 1809, but when this went poorly, the government deigned not to remove any others, for the time being, other than most of the Shawnee over the Shawnee War. This was later undone after the Trail of Tears, which led the government into a scramble to convince all the remaining Natives in Ohio to relocate west peacefully. The last known full blood Wyandot to live in Ohio was Bill Moose (1836–1937). He gave a list of 12 individuals/families who remained behind removal. Draper Manuscripts also show that a few Shawnee, Mingo (mainly Seneca-Cayuga), and Lenape remained behind to. Also Mohawk and Brotherton (Narragansett) families as well.

Starting in the early 19th century, after the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase, Congress began investing heavily in trying to convince Natives in the East to relocate west of the Mississippi. The Lenape were a test, and were removed in 1809, but when they complained that the natives of that region were being aggressive towards them and there wasn't enough to hunt and forage, the project was scrapped for several more decades.[48]

The U.S. Congress prohibited slavery in the territory. (Once the population grew and the territory achieved statehood, the citizens could have legalized slavery, but chose not to do so.) The states of the Midwest would be known as Free States, in contrast to those states south of the Ohio River. Migrants to the latter came chiefly from Virginia and other slave-holding states, and brought their culture and slaves with them.

As Northeastern states abolished slavery in the coming two generations, the free states would be known as Northern States. The Northwest Territory originally included areas previously called Ohio Country and Illinois Country. As Ohio prepared for statehood, Indiana Territory was carved out, reducing the Northwest Territory to approximately the size of present-day Ohio plus the eastern half of Michigan's lower peninsula and a sliver of land in southeastern Indiana along Ohio's western border called "The Gore".

Statehood

With Ohio's population reaching 45,000 in December 1801, Congress determined that the population was growing rapidly and Ohio could begin the path to statehood. The assumption was the territory would have in excess of the required 60,000 residents by the time it became a state. Congress passed the Enabling Act of 1802 that outlined the process for Ohio to seek statehood. The residents convened a constitutional convention. They used numerous provisions from other states and rejected slavery.

On February 19, 1803, President Jefferson signed the act of Congress that approved Ohio's boundaries and constitution. Congress did not pass a specific resolution formally admitting Ohio as the 17th state. The current custom of Congress' declaring an official date of statehood did not begin until 1812, when Louisiana was admitted as the 18th state.

Shawnee War and War of 1812

Starting around 1809, Shawnee leaders once again began to rally support to resist the United States. Under Shawnee chief Tecumseh, the Tecumseh's War officially began in Ohio in 1810. When the War of 1812 began, the British forces from Canada entered Ohio and merged their forces with the Shawnee. This continued until Tecumseh was killed at the Battle of the Thames in 1813. While most of the Shawnee fought in the war, many stayed out of the conflict- particularly in the groups referred to as the Piqua and Makojay, due to the influence of chief Black Hoof.[49] As a result, Piqua and Makojay both remained in Ohio after the rest were removed to the Missouri-Arkansas-Texas area. The Piqua would later be forcibly removed by the U.S. during the Indian removals following the Trail of Tears, though the Makojay vanished after Black Hoof's death.[50]

In 1812, the United States declared war on the United Kingdom. The Royal Navy, in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars and constantly in need of manpower, had begun stopping American ships and impressing British deserters who had fled to the United States, angering the U.S. government and public and leading to a sharp deterioration in Anglo-American relations. In addition, the British also supported Native Americans resisting the invasion of their traditional homelands by American colonizers. After war was declared, U.S. troops launched several unsuccessful invasions of Canada. Ohio played a key role in the War of 1812, as it was on the front line in the Western theater and the scene of several notable battles both on land and in Lake Erie. On September 10, 1813, the Battle of Lake Erie, one of the major battles, took place in Lake Erie near Put-in-Bay, Ohio. The American victory in the battle led to the U.S. gaining control over the Great Lakes for a period of time.

The outcome of Tecumseh's War also caused the Creek War in Alabama in 1813. Tecumseh had approached several tribes there for help beforehand, but all had ignored his pleas, despite support. The Red Sticks, a Muscogee faction hostile to U.S. encroachment, began attacking American troops, aiming to drive them from their homelands. Other Muscogee who didn't support the Red Sticks fought alongside the United States, which eventually defeated the Red Sticks after the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.[51]

Indian Removals

Ultimately, after the United States government used the Indian Removal Act of 1830 to force countless Native American tribes on the Trail of Tears, where all the southern states except for Florida were successfully emptied of Native peoples, the US government panicked because a majority of tribes did not want to be forced out of their own lands. Fearing further wars between Native tribes and American settlers, they pushed all remaining Native tribes in the East to migrate west against their own will, including all remaining tribes in Ohio. It is said that Ohio may actually have been a part of the Trail of Tears, according to The Other Trail of Tears: The Removal of the Ohio Indians by Mary Stockwell.[52][53]

In 1838, the United States sent 7,000 soldiers to remove 16,000 Cherokee by force. Whites looted their homes. The largest Trail of Tears began, eventually taking 4,000 Indian lives. The Removal Act opened 25 million acres to white settlement and slavery. Upper Sandusky's traditionalist Wyandot go to Washington, D.C. to try to promote a separate removal agreement, but they are rejected. They return home, and their chief pulls a knife at a tribal council and lands in jail.[54] The final tribe to leave were the Wyandot in 1843.[55]

Industrialization

Throughout much of the 19th century, industry was rapidly introduced to complement an existing agricultural economy. One of the first iron manufacturing plants opened near Youngstown in 1804 called Hopewell Furnace. By the mid-19th century, 48 blast furnaces were operating in the state, most in the southern portions of the state.[56] Discovery of coal deposits aided the further development of the steel industry in the state, and by 1853 Cleveland was the third largest iron and steel producer in the country. The first Bessemer converter was purchased by the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company, which eventually became part of the U.S. Steel Corporation following the merger of Federal Steel Company and Carnegie Steel, the first billion-dollar American corporation.[56] The first open-hearth furnace used for steel production was constructed by the Otis Steel Company in Cleveland, and by 1892, Ohio ranked as the 2nd-largest steel producing state behind Pennsylvania.[56] Republic Steel was founded in Youngstown in 1899, and was at one point the nation's third largest producer. Armco, now AK Steel, was founded in Middletown also in 1899.

Tobacco processing plants were founded in Dayton by the 1810s and Cincinnati became known as "Porkopolis" in being the nation's capital of pork processing, and by 1850 it was the third largest manufacturing city in the country.[56] Mills were established throughout the state, including one in Steubenville in 1815 which employed 100 workers. Manufacturers produced farming machinery, including Cincinnati residents Cyrus McCormick, who invented the reaper, and Obed Hussey, who developed an early version of the mower.[57] Columbus became known as the "Buggy Capital of the World" for its nearly two dozen carriage manufacturers.[citation needed] Dayton became a technological center in the 1880s with the National Cash Register Company.[58] For roughly ten years during the Ohio Oil Rush in the late 19th century, the state enjoyed the position of leading producer of crude oil in the country. By 1884, 86 oil refineries were operating in Cleveland, the home of Standard Oil, making it the "oil capital of the world",[59] while producing the world's first billionaire, John D. Rockefeller.

Herbert H. Dow founded the Dow Chemical Company in Cleveland in 1895, today the world's second largest chemical manufacturer. In 1898 Frank Seiberling named his rubber company after the first person to vulcanize rubber, Charles Goodyear, which today is known as Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. Seeing the need to replace steel-rimmed carriage tires with rubber, Harvey Firestone started Firestone Tire and Rubber Company and began selling to Henry Ford. The Ohio Automobile Company eventually became known as Packard, while Benjamin Goodrich entered the rubber industry in 1870 in Akron, founding Goodrich, Tew & Company, better known as the Goodrich Corporation in the present era.

By the late 19th century, Ohio had become a global industrial center.[60] Natural resources contributed to the industrial growth, including salt, iron ore, timber, limestone, coal, and natural gas, and the discovery of oil in northwestern Ohio led to the growth of the port of Toledo.[60] By 1908, the state had 9,581 miles of railroad linking coal mines, oil fields, and industries with the world.[60] Commercial enterprise began to prosper around towns with banks.[60]

Innovation

William Procter and James Gamble started a company which produced a high quality, inexpensive soap called Ivory, which is still the best known product today of Procter & Gamble. Michael Joseph Owens invented the first semi-automatic glass-blowing machine while working for the Toledo Glass Company.[61] The company was owned by Edward Libbey, and together the pair would form companies which ultimately became known as Owens-Illinois and Owens Corning.

Wilbur and Orville Wright invented the first airplane in Dayton.

Charles Kettering invented the first automatic starter for automobiles, and was the co-founder of Delco Electronics, today part of Delphi Corporation. The Battelle Memorial Institute perfected xerography, resulting in the company Xerox. At Cincinnati's Children's Hospital, Albert Sabin developed the first oral polio vaccine, which was administered throughout the world.

In 1955, Joseph McVicker tested a wallpaper cleaner in Cincinnati schools, eventually becoming known as the product Play-Doh. The same year the Tappan Stove Company created the first microwave oven made for commercial, home use. James Spangler invented the first commercially successful portable vacuum cleaner, which he sold to The Hoover Company.

African American inventors based in Ohio achieved prominence. After witnessing a car and carriage crash, Garrett Morgan invented one of the earliest traffic lights; he was a leader in the Cleveland Association of Colored Men. Frederick McKinley Jones invented refrigeration devices for transportation which ultimately led to the Thermo King Corporation. In Cincinnati, Granville Woods invented the telegraphony, which he sold to a telephone company. John P. Parker of Ripley invented the Parker Pulverizer and screw for tobacco processes.

Infrastructure

Ohio's economic growth was aided by their pursuit of infrastructure. By the late 1810s, the National Road crossed the Appalachian Mountains, connecting Ohio with the east coast. The Ohio River aided the agricultural economy by allowing farmers to move their goods by water to the southern states and the port of New Orleans. The construction of the Erie Canal in the 1820s allowed Ohio businesses to ship their goods through Lake Erie and to the east coast, which was followed by the completion of the Ohio and Erie Canal and the connection of Lake Erie with the Ohio River. This gave the state complete water access to the world within the borders of the United States. Other canals included Miami and Erie Canal.[57] The Welland Canal would eventually give the state alternative global routes through Canada.

The first railroad in Ohio was a 33-mile line completed in 1836 called the Erie and Kalamazoo Railroad, connecting Toledo with Adrian, Michigan. The Ohio Loan Law of 1837 allowed the state to loan one-third of construction costs to businesses, passed initially to aid the construction of canals, but instead used heavily for the construction of railroads. The Little Miami Railroad was granted a state charter in 1836 and was completed in 1848, connecting Cincinnati with Springfield. Construction of a commuter rail began in 1851 called the Cincinnati, Hamilton, and Dayton Railroad. This allowed the affluent of Cincinnati to move to newly developed communities outside the city along the rail. The Ohio and Mississippi Railroad was given financial support from the city of Cincinnati and eventually connected them with St. Louis, while the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad crossed the Appalachians in the mid-1850s and connected the state with the east coast.[62]

The investment in infrastructure complemented Ohio's central location and put it at the heart of the nation's transportation system traveling north and south and east and west, and also gave the state a headstart during the national industrialization process which occurred between 1870 and 1920.[58]

Water ports sprang up along Lake Erie, including the Port of Ashtabula, Port of Cleveland, Port of Conneaut, Fairport Harbor, Port of Huron, Port of Lorain, Port of Marblehead, Port of Sandusky, and Port of Toledo. The Port of Cincinnati was built on the Ohio River.

Following the commercialization of air travel, Ohio became a key route for east to west transportation. The first commercial cargo flight occurred between Dayton and Columbus in 1910. Cleveland Hopkins International Airport was built in 1925 and became home to the first air traffic control tower, ground to air radio control, airfield lighting system, and commuter rail link.

The Interstate Highway System brought new travel routes to the state in the mid-20th century, further making Ohio a transportation hub.

Urbanization and commercialization

With the rapid increase of industrialization in the country in the late 19th century, Ohio's population swelled from 2.3 million in 1860 to 4.2 million by 1900. By 1920, nine Ohio cities had populations of 50,000 or more.[58]

The rapid urbanization brought about a growth of commercial industries in the state, including many financial and insurance institutions. The National City Corporation was founded in 1849, today part of PNC Financial Services. Cleveland's Society for Savings was founded in 1849, eventually becoming part of KeyBank. The Bank of the Ohio Valley opened in 1858, becoming known as Fifth Third Bank today. City National Bank and Trust Company was founded in 1866 in Columbus, eventually becoming Bank One. The American Financial Group was founded in 1872 and the Western & Southern Financial Group in 1888 in Cincinnati. The Farm Bureau Mutual Automobile Insurance Company was founded in Columbus in 1925, today known as the Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company.

Major retail operations emerged in the state, including Kroger in 1883 in Cincinnati, today second only to Walmart. Federated Department Stores was founded in Columbus in 1929, known today as Macy's. The Sherwin-Williams Company was founded in 1866 in Cleveland.

Frisch's Big Boy was opened in 1905 in Cincinnati. American Electric Power was founded in Columbus in 1906. The American Professional Football Association was founded in Canton in 1922, eventually becoming the National Football League. The Cleveland Clinic was founded in 1921 and presently is one of the world's leading medical institutions.

Education

Education has been an integral part of Ohio culture since its early days of statehood. In the beginning, mothers usually educated their children at home or paid for their children to attend smaller schools in villages and towns.[63] Early on, the US was interested in creating a national public schooling system, but the irony came to be that, in Ohio, the various religious groups who had settled here refused to allow one another any say in what their own children would be taught, causing the issue to be constantly put on hold. In 1821 the state passed a tax to finance local schools.[64] In 1822, Caleb Atwater lobbied the legislature and Governor Allen Trimble to establish a commission to study the possibility of initiating public, common schools. Atwater modeled his plan after the New York City public school system. After public opinion in 1824 forced the state to find a resolution to the education problem, the legislature established the common school system in 1825 and financed it with a half-million property levy.[63]

They ultimately chose to relax state authority over school curriculum and gave Ohio schools regional authority over the matter. It would remain as such until the 20th century, but has caused a fairly erratic, confusing and sometimes lacking schooling experience in some subjects, even if generally adequate to get by.

School districts formed, and by 1838 the first direct tax was levied allowing access to school for all.[64] The first appropriation for the common schools came in 1838, a sum of $200,000. The average salary for male teachers in some districts during this early period was $25/month and $12.50/month for females.[65] By 1915, the appropriations for the common schools totaled over $28 million.[64] The first middle school in the nation, Indianola Junior High School (now the Graham Expeditionary Middle School), opened in Columbus in 1909. McGuffey Readers was a leading textbook originating from the state and found throughout the nation.

Original universities and colleges in the state included the Ohio University, founded in Athens, in 1804, the first university in the old Northwest Territory and ninth-oldest in the United States. Miami University in Oxford, Ohio was founded in 1809, the University of Cincinnati in 1819, Kenyon College in Gambier in 1824, Western Reserve University in Cleveland in 1826, Capital University in Columbus in 1830, Xavier University in Cincinnati and Denison University in Granville in 1831, Oberlin College in 1833, Marietta College in 1835, the Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware in 1842, Mount Union College in 1846, and the University of Dayton in 1850. Wilberforce University was founded in 1856 and the University of Akron and Ohio State University followed in 1870, with the University of Toledo in 1872.

The first dental school in the United States was founded in the early 19th century in Bainbridge. The Ohio School for the Blind became the first of its kind in the country, located in Columbus.

After 2000, Ohio State government began experimentally exerting more control over schools, as they attempted to help the state's education system evolve with the times. As of 2020, it largely seems to have done just as much harm as good and re-exposed a lot of the issues inherent in how Ohio schooling was originally organized, which they are now desperately trying to solve.[66][67]

In 2007, Governor Ted Strickland signed legislation organizing the University System of Ohio, the nation's largest comprehensive public system of higher education.

Social history

Religion

Rural Ohio in the 19th century was noted for its religious diversity, tolerance and pluralism, according to Smith (1991). With so many active denominations, no one dominated and, increasingly, tolerance became the norm. Germans from Pennsylvania and from Germany brought Lutheran and Reformed churches and numerous smaller sects such as the Amish. Yankees brought Presbyterians and Congregationalists. Revivals during the Second Great Awakening spurred the growth of Methodist, Baptist and Christian (Church of Christ) churches. The building of many denominational liberal arts colleges was a distinctive feature of the 19th century. By the 1840s German and Irish Catholics were moving into the cities, and after the 1880s Catholics from eastern and southern Europe arrived in the larger cities, mining camps, and small industrial centers. Jews and Eastern Orthodox settlements added to the pluralism, as did the building of black Baptists and Methodist churches in the cities.[68]

During the Progressive Era, Washington Gladden was a leader of the Social Gospel movement in Ohio. He was the editor of the influential national magazine the Independent after 1871, and as pastor of the First Congregational Church of Columbus, Ohio from 1882 to his death in 1918. Gladden crusaded for Prohibition, resolving conflicts between labor and capital; he often denounced racial violence and lynching.[69]

Ethnic groups

Early Ohio state culture was a product of Native American cultures, which were pushed away between 1795 and 1843. Many of Native American descent did remain, but had often converted to some form of Christianity, and/ or married into European descended families, so the cultures themselves did not last here. This was especially exasperated in the late 19th century, when racial violence against all sorts of people- including Native Americans- reached such a horrifying peak nationwide, that most such people went out of their ways to seem as white as possible.[70]

It was easier for people who were only part Native, as most Ohioans no longer knew what such people really looked like and their skin was fair enough that they could claim Italian, Hispanic or Greek descent and disappear into those communities. Still, Ohio does have plenty today who claim Iroquoian, Lenape, Chippewa, Shawnee, Cherokee (usually Shattara/ Shenandoah, not really Cherokee) or Blackfoot (Saponi-Tutelo and Manahoac) descent and are proud of it.

The northeastern part of Ohio was settled by Yankees from Connecticut, and pioneers from New York and Pennsylvania. The Connecticut Western Reserve became the center for modernization and reform.[71] They were sophisticated, educated, and open minded, as well as religious.[71] Some of the original settlers from Connecticut were Amos Loveland, a revolutionary soldier, and Jacob Russell.[71] They faced a rough wilderness life, where the common living arrangement was the log cabin.[71] As the pioneer culture faded in the mid-19th century, Ohio had over 140,000 citizens of native New England origin, including New York.[72] One of the New Yorkers who came to the state during this period was Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, whose church in Kirtland was the home of the movement for a period of time.

Other early pioneers came from the Mid-Atlantic states, especially Pennsylvania and Virginia, some settling on military grant lands in the Virginia Military District. From Virginia came members of the Harrison family of Virginia, who rose to prominence in the state, producing Ohio's first of eight U.S. Presidents. William Henry Harrison's campaign of 1840 came to represent the pioneer culture of Ohio, symbolized by his Log cabin campaign. The theme song of his campaign, the "Log Cabin Song",[73] was authored by Otway Curry, who was a nationally known poet and author.[74]

Ohio was largely agricultural before 1850, although gristmills and local forges were present. Clear-cut gender norms prevailed among the farm families who settled in the Midwestern region between 1800 and 1840. Men were the breadwinners and financial providers for their families, who considered the profitability of farming in a particular location – or "market-minded agrarianism". They had an almost exclusive voice regarding public matters, such as voting and handling the money. During the migration westward, women's diaries show little interest in and financial problems, but great concern with the threat of separation from family and friends. Furthermore, women experienced a physical toll because they were expected to have babies, supervise the domestic chores, care for the sick, and take control of the garden crops and poultry. Outside the German American community, women rarely did fieldwork on the farm. The women set up neighborhood social organizations, often revolving around church membership, or quilting parties. They exchanged information and tips on child-rearing, and helped each other in childbirth.[75]

Large numbers of German Americans arrived from Pennsylvania, augmented by new immigrants from Germany. They all clung to their German language and Protestant religions, as well as their specialized tastes in food and beer. Brewing was a main feature of the German culture. Their villages from this period included the German Village in Columbus. They also founded the villages of Gnadenhutten in the late 18th century; Bergholz, New Bremen, New Berlin, Dresden, and other villages and towns. The German Americans immigrating from the Mid-Atlantic states, especially eastern Pennsylvania, brought with them the Midland dialect, which is still found throughout much of Ohio.[76][77] For instance, in Philadelphia water is pronounced with a long o versus the normal short o, the same as in many areas of Ohio. African Americans of the Underground Railroad began coming to the state, some settling, others passing through on the way to Canada. Universities and colleges opened up all over the state, creating a more educated culture.

By the last half of the 19th century, the state became more diverse culturally with new immigrants from Europe, including Ireland and Germany. The Forty-Eighters from Central Europe settled the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in Cincinnati, while the Irish immigrants settled throughout the state, including Flytown in Columbus. Other immigrants from Russia, Turkey, China, Japan, Finland, Greece, Italy, Romania, Poland, and other places came in the latter years.[78] Around the start of the 20th century, rural southern European Americans and African Americans came north in search of better economic opportunity, infusing Hillbilly culture into the state. Newer ethnic villages emerged, including the Slavic Village in Cleveland and the Italian Village and Hungarian Village in Columbus. Howard Chandler Christy, born in Morgan County, became a leading American artist during this century, as well as composer Dan Emmett, founder of the Blackface tradition. Ohio's mines factories and cities attracted Europeans. Irish Catholics poured in to construct the canals, railroads, streets and sewers in the 1840s and 1850s.[79]

After 1880, the coal mines and steel plants attracted families from southern and eastern Europe. A large influx of people moving into Ohio from neighboring West Virginia and Kentucky also occurred. The sparsely populated regions of Appalachia had largely been stripped of resources by logging and mining companies, leaving little and few prospects for the locals. Steel and rubber manufacturers were even known to scout these regions for new workers and invested in infrastructure and the building of new suburbs to lure them in. Places like Akron, OH were almost single-handedly built this way, as the modern city was only a small town prior to the early-mid 20th century.

By 1901, the Midwest (Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio) had absorbed 5.8 million foreign immigrants and another million by 1912.[80]

Immigration was cut off by the World War in 1914, allowing the ethnic communities to Americanize, grow much more prosperous, served in the military, and abandon possible plans to return to the old country.[81] Flows were very low between 1925 and 1965, then began to increase again, this time with many arrivals from Asia and Mexico.

Since then, there were larger influxes from the Jewish community, following World War II and a spike in the numbers of Middle Easterners following successive conflicts in the region during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Ohio has also become a common destination for foreign college students worldwide, with many choosing to remain in the state after.

Popular culture

Industrialization brought a shift culturally as urbanization and an emerging middle class changed society. Athletics became increasingly popular as the first professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Reds, started playing at that level in 1869, and football leagues emerged. Bathhouses and rollercoasters became a popular past time with the opening of Cedar Point in 1870. Theaters and saloons sprang up,[82] and more restaurants opened. Entertainment venues opening in Cleveland included the Playhouse Square Center, Palace Theatre, Ohio Theatre, State Theatre, and the Karamu House. Langston Hughes grew up in Cleveland and developed many of his plays at the Karamu House. In Columbus they opened the Southern Theatre in 1894, as well as their own Palace Theatre and Ohio Theatre, which hosted performers such as Jack Benny, Judy Garland, and Jean Harlow. The Lincoln Theatre hosted performers like Count Basie. The Taft Theatre opened in 1928 in Cincinnati.

The Roaring Twenties brought prohibition, bootlegging and speakeasies to the state, as well as the swing dance culture.[83] Cincinnati became the headquarters of the "king of bootlegging" George Remus, who made $40 million by the end of 1922.[84] The Anti-Saloon League had been powerful and Ohio, and the Women's Christian Temperance Union was still headquartered there; the Ku Klux Klan was active in the 1920s. However these organizations steadily lost influence after 1925.

Perhaps the biggest invention in Ohio and the US was the invention of flight by Dayton's Orville and Wilbur Wright. Starting this invention in their bike shop in what is now Dayton's west side, the Wright's brought flight to the world in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The brothers gained the mechanical skills essential to their success by working for years in their Dayton, Ohio-based shop with printing presses, bicycles, motors, and other machinery. Their work with bicycles in particular influenced their belief that an unstable vehicle such as a flying machine could be controlled and balanced with practice. From 1900 until their first powered flights in late 1903, they conducted extensive glider tests that also developed their skills as pilots. Their shop employee Charlie Taylor became an important part of the team, building their first airplane engine in close collaboration with the brothers. The very first airplane passenger was the Wright's own mechanic, Charles Furnas of West Milton, Ohio.

Depression years

During the 1930s, the Great Depression struck the state hard. American Jews watched the rise of the Third Reich with apprehension. Cleveland residents Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created the Superman comic character in the spirit of the Jewish golem. Many of their comics portrayed Superman fighting and defeating the Nazis.[85][86]

Artists, writers, musicians and actors developed in the state and often moved to other cities which were larger centers for their work. They included Zane Grey, Milton Caniff, George Bellows, Art Tatum, Roy Lichtenstein, and "king of the cowboys" Roy Rogers. Alan Freed, who emerged from the swing dance culture in Cleveland, hosted the first live rock 'n roll concert in Cleveland in 1952. Famous filmmakers include Steven Spielberg, Chris Columbus and the original Warner Brothers, who set up their first movie theatre in Youngstown, OH before that company later relocated to California. The state produced many popular musicians, including Dean Martin, Doris Day, The O'Jays, Marilyn Manson, Dave Grohl of Nirvana and Foo Fighters fame, Devo, Macy Gray and The Isley Brothers.

The NFL was originally founded in Ohio and the state has since given us many famous stars across various sports. Other famous individuals- native Ohioans and those who were just later associated with the state- include Annie Oakley, Clarence Darrow, Thomas Edison, Neil Armstrong and less beloved figures, like President William McKinley and General George Custer.

Civil War

During the Civil War (1861–65) Ohio played a key role in providing troops, military officers, and supplies to the Union army. Due to its central location and burgeoning population, Ohio was both politically and logistically important to the war effort. Despite the state's boasting a number of very powerful Republican politicians, it was divided politically. Portions of Southern Ohio followed the Peace Democrats under Clement Vallandigham and openly opposed President Lincoln's policies. Ohio played an important part in the Underground Railroad prior to the war, and remained a haven for escaped and runaway slaves during the war years.[87]

The third most populous state in the Union at the time, Ohio raised nearly 320,000 soldiers for the Union army, third behind only New York and Pennsylvania. Nearly 7,000 Buckeye soldiers were killed in action.[88] Several leading generals were from the state, including Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Philip H. Sheridan.

Only two minor battles were fought within its borders. Morgan's Raid in the summer of 1863 alarmed the populace.[89] Ohio troops fought in nearly every major campaign during the war.

Prison camps

Its most significant Civil War site is Johnson's Island, located in Sandusky Bay of Lake Erie. Barracks and outbuildings were constructed for a prisoner of war depot, intended chiefly for officers. Over three years more than 15,000 Confederate soldiers were held there. The island includes a Confederate cemetery where about 300 soldiers were buried.[90]

Camp Chase Prison was a Union Army prison in Columbus. There was a plot among prisoners to revolt and escape in 1863. The prisoners expected support from Copperheads and Vallandigham, but never did revolt.[91]

Veterans

Ohio has been involved in regional, national, and global wars since statehood, and veterans have been a powerful social and political force at the local and state levels. The organization of Civil War veterans, the Grand Army of the Republic, was a major player in local society and Republican politics in the last third of the 19th century. The American Veterans of Foreign Service was established in 1899 in Columbus, ultimately becoming known as the Veterans of Foreign Wars in 1913. The state has produced 319 Medal of Honor recipients,[92] including the country's first recipient, Jacob Parrott.

In 1886, the state authorized the creation of the Ohio Veterans Home in Sandusky and a second one created in 2003 in Georgetown to provide for soldiers facing economic hardship. Over 50,000 veterans have lived at the Sandusky location as of 2005.[93] Since World War I, the state has paid stipends to veterans of wars, including in 2009, authorizing funds for soldiers of the Gulf and Afghanistan wars.[94] The state also provides free in-state tuition to any veteran regardless of state origin at their colleges.[95]

Ohio politics

Rebellion of 1820

In 1820, the legislature then passed legislation which nullified the federal court order as well as the operations of the Bank of the United States within their borders.[96] The state ignored further federal court orders, writs, and denied immunities to the federal government.[97] Their actions were considered the complete destruction of federal standing in the state and an attempted overthrow of the federal government.[98] Ohio forcefully applied their iron law against the federal government until 1824, when the United States Supreme Court ruled they had no authority to tax the federal bank in the landmark case originating from the state: Osborn v. Bank of the United States. They then followed by passing an act in 1831 to withdraw state protections for the Bank of the United States.[99]

Although the nullification of 1820 in Ohio was inspired by resolutions passed in Virginia and Kentucky in 1798 and 1800, the language of their resolution from 1820 would find its place in South Carolina's nullification of 1832 and secession articles of southern states in 1861.[99][100]

Sovereignty

The rebellion of 1820 firmly rooted the tradition of sovereignty in the state. In 1859, Governor Salmon P. Chase reaffirmed that tradition, stating: "We have rights which the Federal Government must not invade — rights superior to its power, on which our sovereignty depends; and we mean to assert those rights against all tyrannical assumptions of authority."[101] Following the War of the Rebellion, the debate over ratification of the Reconstruction Amendments reignited the sovereignty movement in Ohio. General Durbin Ward stated: "Fellow citizens of Ohio, I boldly assert that the States of this Union have always had, both before and since the adoption of the Constitution of the United States, entire sovereignty over the whole subject of suffrage in all its relations and bearings. Ohio has that sovereignty now, and it cannot be taken from her".[102]

As recently as 2009, the tradition re-emerged, with an Ohio sovereignty resolution[103] passing in the state senate,[104] and signatures being collected to place a state sovereignty amendment on the ballot in 2011.[105]

Anti-slavery

Ohio's roots as an anti-slavery and abolitionist state go back to its territorial days in the Northwest Territory, which forbade the practice. When it became a state, the constitution expressly outlawed slavery.[106] Many Ohioans were members of anti-slavery organizations, including the American Anti-Slavery Society and American Colonization Society.[107] Ohioan Charles Osborn published the first abolitionist newspaper in the country, The Philanthropist, and in 1821, the father of abolition Benjamin Lundy began publishing his newspaper the Genius of Universal Emancipation.[107]

Ohio was a key stop on the Underground Railroad where prominent abolitionists played a role, including John Rankin. Ohio resident Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the famous book Uncle Tom's Cabin, which was largely influential in shaping the opinion of the north against slavery.

Ohio in national politics

As a closely contested state, Ohio was the top choice of Republicans, and often also as Democrats, for place on the national ticket as candidate for president or vice president.

Between Lincoln and Hoover, every Republican president who did not gain the office by the death of his predecessor was born in Ohio; Ulysses Grant, although born in Ohio, was legally a residence of Illinois when he was elected.[108]

By electing so many of her sons to the presidency, Ohio gained a role in politics disproportionate to its size. Several reasons came together. Ohio was a microcosm of the United States, balanced closely between the parties, and at the crossroads of America: between the South, the Northeast, and the developing West, and influenced by each. Its ethnic, religious, and cultural elements were a microcosm of the North. Its cutthroat politics trained candidates in how to win. A leading Ohio politician was "Available"—that is, well-suited and electable. Thus, in most presidential years, the governor of Ohio was deemed more available than the governor of the larger states of New York or Pennsylvania.[109]

This legend built on itself as the state sent seven men to the White House and four more became vice president. Many others won major patronage plums. Between 1868 and 1924, not only did Ohio supply the most presidents, it supplied the most Cabinet members, and the most federal officeholders. Ohio-born Rutherford B. Hayes (1876), James A. Garfield (1880) and Benjamin Harrison (1888) were each nominated from a convention that had deadlocked, and where the delegates chose to turn to a candidate who could carry Ohio. In each case they did, and won the presidency. According to historian Andrew Sinclair, "the potency of the Ohio myth gave its favorite sons a huge advantage in a deadlocked convention".[110]

Progressive era

The Progressive Era brought about change in the state, although the state had been at the forefront of the movement decades before. In 1852, Ohio passed its first child labor laws, and in 1885 adopted prosecution powers for violations.[111] In 1886, the American Federation of Labor was formed in Columbus, culminating in the passage of workers' compensation laws by the early 20th century.[112]

Women's rights

Victoria Woodhull, the first female candidate for president in 1872, and Second Lady Cornelia Cole Fairbanks, credited with paving the way for the modern American female politician, were leaders in the women's suffrage movement. Ohio was the second state to hold a women's rights convention, the Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850.[113] The public voted on women's suffrage in 1912, which failed, but the state ultimately adopted the 19th amendment in 1920. Ohio-native and President William Howard Taft signed the White-Slave Traffic Act in 1910, which sought to end human trafficking and the sex slave trade.

The Anti-Saloon League was founded in 1893 in Oberlin, which saw political success with the passage of the Volstead Act in 1918.

Early through mid-20th century

Progressive movement

Ohio was active in the Progressive movement in the early 20th century. It was notable for the high level of municipal activism. The key leaders included Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones in Toledo, Tom L. Johnson in Cleveland, Washington Gladden in Columbus, and James M. Cox in Cincinnati. They combined a commitment to popular rule to neutralize machine bosses, opposition to monopolistic trusts and railroads, and a quest to reduce waste and inefficiency.[114][115]

Constitutional Convention of 1912

In 1912 a Constitutional Convention was held with Charles Burleigh Galbreath as Secretary. The result reflected the concerns of the Progressive Era. The constitution introduced the initiative and the referendum, and provided for the General Assembly to put questions on the ballot for the people to ratify laws and constitutional amendments originating in the Legislature. Under the Jeffersonian principle that laws should be reviewed once a generation, the constitution provided for a recurring question to appear every 20 years on Ohio's general election ballots. The question asks whether a new constitutional convention is required. Although the question has appeared in 1932, 1952, 1972, and 1992, the people have not found the need for a convention. Instead, constitutional amendments have been proposed by petition and the legislature hundreds of times and adopted in a majority of cases.[116]

Ku Klux Klan

In the early 1920s the Ku Klux Klan attracted tens of thousands of Protestants into membership. Its organizers warned of the need to purify America, especially against the influence of Catholics, bootleggers, and corrupt politicians. There were no dues but there was a large membership fee and expensive white constumes. The chapters were set up for the financial benefit of the organizers, and once it was set up, they moved on leaving the chapter without an agenda or money. It typically accomplished very little.[117] The Klan collapsed and virtually disappeared after 1925.[118]

Great Depression

Ohio was hit very hard by the Great Depression in the 1930s. In 1932, unemployment for the state reached 37.3%. By 1933, 40% of factory workers and 67% of construction labor were unemployed.[119] The voters supported Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, 1936, and 1940, with large margins in the cities. Roosevelt's New Deal had provided hundreds of thousands of jobs for the unemployed and their sons. By 1944 the depression was gone, relief had ended and Republican Governor John W. Bricker was running for vice-president. Roosevelt lost the state but still won reelection.[120]

World War II

Ohio played a major role in World War II, especially in providing manpower, food, and munitions to the Allied cause. Ohio manufactured 8.4 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking fourth among the 48 states.[121]

Cold War

Ohio became heavily anti-Communist during the Cold War following World War II. Time magazine reported in 1950 that police officers in Columbus were warning youth clubs to be suspicious of communist agitators.[122] Campbell Hill in Bellefontaine became the site of a main U.S. Cold War base and a precursor to NORAD. Anti-communist personalities emerged from the state, including Janet Greene of Columbus, the political right's answer to Joan Baez. Her songs included "Commie Lies", "Poor Left Winger", and "Comrade's Lament".[123] Ohio was the scene of the Kent State Massacre, where four anti-Vietnam war protesters, although peaceful themselves, were shot dead, by badly frightened and poorly trained guardsmen. In the 1980s Ohio heavily supported the elections of President Ronald Reagan and his celebrated his success in winning the Cold War.

Ohio became an industrial magnet in the 1950s. By 1960, 10% of the population had been born in nearby Kentucky, West Virginia or Tennessee.[124]

Ohio was an important state in the developing ties between the United States and the People's Republic of China in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[125]: 59 Relations between the two countries normalized in 1979, during the second term of Ohio governor Jim Rhodes.[125]: 112 Rhodes sought to encourage U.S.-China economic ties, viewing China as a potential market for Ohio machinery exports for companies like Timken Company and Parker Hannifin.[125]: 112 In July 1979, Rhodes led State of Ohio Trade Mission to China.[125]: 112 The trip resulted in developing economic ties, a sister state-province relationship with Hubei province, long-running Chinese exhibitions at the Ohio State Fair, and major academic exchanges between Ohio State University and Wuhan University.[125]: 113

Un-American activities

The Ohio Un-American Activities Committee was a government agency which existed to collect information on citizens with communist sympathies,[126] resulting in 15 convictions, 40 indictments, and 1,300 suspects. Governor Frank Lausche generally opposed the committee, but his vetoes were overridden by the legislature.[127] The state forced their employees to sign a loyalty oath, promising "to defend the state against foreign and domestic enemies", in order to receive a paycheck. Professors and Holocaust survivors Bernhard Blume and Oskar Seidlin were among those required to take the oath.[128] Ohio barred communists from receiving unemployment benefits.[129]

Late 20th century to present

Ohioans have supported movie making. Five Academy Award-winning films of the late 20th century were partly produced in the state, including The Deer Hunter, Rain Man, Silence of the Lambs, Terms of Endearment, and Traffic.

In the 21st century, Ohio remains connected to the regional, national, and global economies. According to U.S. Census Bureau statistics, the foreign-born share of Ohio's population increased from 2.4% in 1990, to 3.0% in 2000, to 4.1% in 2013.[130] As of 2015, 49.7% of immigrants to Ohio had become naturalized U.S. citizens.[130] Immigrants have substantial economic importance to Ohio, as taxpayers, entrepreneurs, consumers, and workers.[130][131] A 2016 study on immigrants in Ohio concluded that immigrants make up 6.7% of all entrepreneurs in Ohio although they are just 4.2% of Ohio's population, and that these immigrant-owned businesses generated almost $532 million in 2014. The study also showed that "immigrants in Ohio earned $15.6 billion in 2014 and contributed $4.4 billion in local, state and federal taxes that year".[131]

In 2015, Ohio gross domestic product (a broad measure of the size of the economy) was $608.1 billion, the seventh-largest economy among the 50 states.[132] In 2015, Ohio's total GDP accounted for 3.4% of U.S. GDP and 0.8% of world GDP.[132] Ohio's GDP per capita in 2015 was $52,363, ranked 26th among the states in GDP per capita.[132] From 2005 to 2015, " Ohio's economy grew more slowly than the U.S. as a whole, growing at an average nominal (i.e., not inflation-adjusted) annual rate of 2.6%, compared to the U.S. average annual growth rate of 3.2% over the same time period.[132] From 2000 to 2016, "the pace of employment growth in Ohio has trailed the national pace ..., except for the three-year period between 2010 and 2013".[132]

Ohio had become nicknamed the "fuel cell corridor"[133] in being a contributing anchor for the region now called the "Green Belt", in reference to the growing renewable energy sector.[134] Although the state experienced heavy manufacturing losses around the start of the 20th century and suffered from the Great Recession, it was rebounding by the second decade in being the country's 6th-fastest-growing economy through the first half of 2010.[135] Politically the state has demonstrated its importance in modern presidential elections, signed international cooperation treaties with foreign provinces and northern American states, has become involved in heated national disputes with southern American states, while producing national leadership. Its athletic teams are among some of the nation's best, and culturally the state continues to produce notable artists while building institutions enshrining its past. Educationally the schools are among the nation's top performers, and militarily Ohio's legacy continues into the present era.

Ohio's transition into the 21st century is symbolized by the Third Frontier program, spearheaded by Governor Bob Taft around the start of the 20th century. This built on the agricultural and industrial pillars of the economy, the first and second frontiers, by aiding the growth of advanced technology industries, the third frontier.[136] It has been widely hailed as one of the nation's most successful government bureaucracies,[137] attracting 637 new high-tech companies to the state and 55,000 new jobs, with an average of salary of $65,000,[138] while having a $6.6 billion economic impact with an investment return ratio of 9:1.[138] In 2010 the state won the International Economic Development Council's Excellence in Economic Development Award, celebrated as a national model of success.[citation needed]

The state's cities have become hubs of modern industry, including Toledo's recognition as a national solar center,[139][140] Cleveland a regenerative medicine research hub,[141] Dayton an aerospace and defense hub, Akron the rubber capital of the world, Columbus a technological research and development hub,[141] and Cincinnati a mercantile hub.[141] Ohio was hit hard by the Great Recession and manufacturing employment losses during the most recent period. The recession cost the state 376,500 jobs[142] and it had 89,053 foreclosures in 2009, a record for the state.[143] The median household income dropped 7% and the poverty rate ballooned to 13.5% by 2009.[144] By the second half of 2010, the state showed signs of rebound in being the nation's sixth-fastest-growing economy.[135]