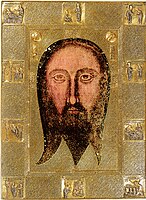

Image of Edessa

According to Christian tradition, the Image of Edessa was a holy relic consisting of a square or rectangle of cloth upon which a miraculous image of the face of Jesus Christ had been imprinted—the first icon (lit. 'image'). The image is also known as the Mandylion (Greek: μανδύλιον, 'cloth' or 'towel'),[1] in Eastern Orthodoxy, it is also known as Acheiropoieton (Greek: Εἰκόν' ἀχειροποίητη, lit. 'icon not made by hand').

In the tradition recorded in the early 4th century by Eusebius of Caesarea,[2] King Abgar of Edessa wrote to Jesus, asking him to come cure him of an illness. Abgar received a reply letter from Jesus, declining the invitation, but promising a future visit by one of his disciples. One of the seventy disciples, Thaddeus of Edessa, is said to have come to Edessa, bearing the words of Jesus, by the virtues of which the king was miraculously healed. Eusebius said that he had transcribed and translated the actual letter in the Syriac chancery documents of the king of Edessa, but who makes no mention of an image.[3] The report of an image, which accrued to the legendarium of Abgar, first appears in the Syriac work the Doctrine of Addai: according to it, the messenger, here called Ananias, was also a painter, and he painted the portrait, which was brought back to Edessa and conserved in the royal palace.[4]

The first record of the existence of a physical image in the ancient city of Edessa (now Urfa) was by Evagrius Scholasticus, writing about 593, who reports a portrait of Christ of divine origin (θεότευκτος), which effected the miraculous aid in the defence of Edessa against the Persians in 544.[5] The image was moved to Constantinople in the 10th century. The cloth disappeared when Constantinople was sacked in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, and is believed by some to have reappeared as a relic in King Louis IX of France's Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. This relic disappeared in the French Revolution.[6]

The provenance of the Edessa letter between the 1st century and its location in his own time are not reported by Eusebius. The materials, according to the scholar Robert Eisenman, "are very widespread in the Syriac sources with so many multiple developments and divergences that it is hard to believe they could all be based on Eusebius' poor efforts" (Eisenman 1997:862).

The Eastern Orthodox Church observes a feast for this icon on August 16, which commemorates its translation from Edessa to Constantinople.

History of the legend

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

The story of the Mandylion is likely the product of centuries of development. The first version is found in Eusebius' History of the Church (1.13.5–1.13.22). Eusebius claimed that he had transcribed and translated the actual letter in the Syriac chancery documents of the king of Edessa. This records a letter written by King Abgar of Edessa to Jesus, asking him to come cure him of an illness. Jesus replies by letter, saying that when he had completed his earthly mission and ascended to heaven, he would send a disciple (Thaddeus of Edessa) to heal Abgar (and does so). At this stage, there is no mention of an image of Jesus.[7]

In AD 384, Egeria, a pilgrim from either Gaul or Spain, was given a personal tour by the Bishop of Edessa, who provided her with many marvellous accounts of miracles that had saved Edessa from the Persians and put into her hands transcripts of the correspondence of Abgarus and Jesus, with embellishments. Part of her accounts of her travels, in letters to her sisterhood, survive. "She naïvely supposed that this version was more complete than the shorter letter which she had read in a translation at home, presumably one brought back to the Far West by an earlier pilgrim".[8] Her escorted tour, accompanied by a translator, was thorough; the bishop is quoted: "Now let us go to the gate where the messenger Ananias came in with the letter of which I have been telling you."[8] There was however, no mention of any image reported by Egeria, who spent three days inspecting every corner of Edessa and the environs.

The next stage of development appears in the Doctrine of Addai [Thaddeus], c. 400, which introduces a court painter among a delegation sent by Abgar to Jesus, who paints a portrait of Jesus to take back to his master:

When Hannan, the keeper of the archives, saw that Jesus spoke thus to him, by virtue of being the king's painter, he took and painted a likeness of Jesus with choice paints, and brought with him to Abgar the king, his master. And when Abgar the king saw the likeness, he received it with great joy, and placed it with great honor in one of his palatial houses.

— Doctrine of Addai, 13

The later legend of the image recounts that because the successors of Abgar reverted to paganism, the bishop placed the miraculous image inside a wall, and setting a burning lamp before the image, he sealed them up behind a tile; that the image was later found again, after a vision, on the very night of the Persian invasion, and that not only had it miraculously reproduced itself on the tile, but the same lamp was still burning before it; further, that the bishop of Edessa used a fire into which oil flowing from the image was poured to destroy the Persians.

The image itself is said to have resurfaced in 525, during a flood of the Daisan, a tributary stream of the Euphrates that passed by Edessa. This flood is mentioned in the writings of the court historian Procopius of Caesarea. In the course of the reconstruction work, a cloth bearing the facial features of a man was discovered hidden in the wall above one of the gates of Edessa.

Writing soon after the Persian siege of 544, Procopius says that the text of Jesus' letter, by then including a promise that "no enemy would ever enter the city", was inscribed over the city gate, but does not mention an image. Procopius is sceptical about the authenticity of the promise, but says that the wish to disprove it was part of the Persian king Khosrau I's motivation for the attack, as "it kept irritating his mind".[9] The Syriac Chronicle of Edessa written in 540-550 also claim divine interventions in the siege, but does not mention the Image.[10]

Some fifty years later, Evagrius Scholasticus in his Ecclesiastical History (593) is the first to mention a role for the image in the relief of the siege,[11] attributing it to a "God-made image", a miraculous imprint of the face of Jesus upon a cloth. Thus we can trace the development of the legend from a letter, but no image in Eusebius, to an image painted by a court painter in Addai, which becomes a miracle caused by a miraculously-created image supernaturally made when Jesus pressed a cloth to his wet face in Evagrius. It was this last and latest stage of the legend that became accepted in Eastern Orthodoxy, the image of Edessa that was "created by God, and not produced by the hands of man". This idea of an icon that was Acheiropoietos (Greek: Αχειροποίητη, lit. 'not made by hand') is a separate enrichment of the original legend: similar legends of supernatural origins have accrued to other Orthodox icons.

The Ancha icon is reputed to be the Keramidion, another acheiropoietos recorded from an early period, miraculously imprinted with the face of Christ by contact with the Mandylion. To art historians it is a Georgian icon of the 6th-7th century.

According to the Golden Legend, which is a collection of hagiographies compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the thirteenth century, the king Abgarus sent an epistle to Jesus, who answered him writing that he would send him one of his disciples (Thaddeus of Edessa) to heal him. The same work adds:

And when Abgarus saw that he might not see God presently, after that it is said in an ancient history, as John Damascene witnesseth in his fourth book, he sent a painter unto Jesu Christ for to figure the image of our Lord, to the end that at least that he might see him by his image, whom he might not see in his visage. And when the painter came, because of the great splendour and light that shone in the visage of our Lord Jesu Christ, he could not behold it, ne could not counterfeit it by no figure. And when our Lord saw this thing he took from the painter a linen cloth and set it upon his visage, and emprinted the very phisiognomy of his visage therein, and sent it unto the king Abgarus which so much desired it. And in the same history is contained how this image was figured. It was well-eyed, well-browed, a long visage or cheer, and inclined, which is a sign of maturity or ripe sadness.[12][13]

Later events

The Holy Mandylion disappeared again after the Sassanians conquered Edessa in 609.[citation needed] A local legend, related to historian Andrew Palmer when he visited Urfa (Edessa) in 1997, relates that the towel or burial cloth (منديل mendil) of Jesus was thrown into a well in what is today the city's Great Mosque.[8] The Christian tradition exemplified in Georgios Kedrenos' Historiarum compendium[14] is at variance with this, John Scylitzes[15] recounting how in 944, when the city was besieged by John Kourkouas, it was exchanged for a group of Muslim prisoners. At that time the Image of Edessa was taken to Constantinople where it was received amidst great celebration by emperor Romanos I Lekapenos, who deposited it in the Theotokos of the Pharos chapel in the Great Palace of Constantinople. Not inconsequentially, the earliest known Byzantine icon of the Mandylion or Holy Face, preserved at Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt, is dated c. 945.[16]

The Mandylion remained under Imperial protection until the Crusaders sacked the city in 1204 and carried off many of its treasures to Western Europe, though the "Image of Edessa" is not mentioned in this context in any contemporary document. Similarly, it has been claimed that the Shroud of Turin disappeared from Constantinople in 1204, when Crusaders looted the city. The leaders of the Crusader army in this instance were French and Italian (from Venice), and it is believed that somehow because of this, the Shroud made its way to France.[17] A small part of a relic, believed to be the same as this, was one of the large group sold by Baldwin II of Constantinople to Louis IX of France in 1241 and housed in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris (not to be confused with the Sainte Chapelle at Chambéry, home for a time of the Shroud of Turin) until it disappeared during the French Revolution.[6]

The Portuguese Jesuit Jerónimo Lobo, who visited Rome in 1637, mentions the sacred portrait sent to King Abgar as being in this city: "I saw the famous relics that are preserved in that city as in a sanctuary, a large part of the holy cross, pieces of the crown and several thorns, the sponge, the lance, Saint Thomas's finger, one of the thirty coins for which the Saviour was sold, the sacred portrait, the one that Christ Our Lord sent to King Abagaro, the sacred staircase on which Christ went up and down from the Praetorium, the head of the holy Baptist, the Column, the Altar on which Saint Peter said mass, and countless other relics."[18]

-

The katholikon of Andronikov Monastery is the oldest (outside the Kremlin) building in Moscow and one of numerous Russian churches dedicated to the Holy Mandylion

-

The Saviour Not Made by Hands, an icon of the Novgorod school, c. 1100

Surviving images

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Three images survive today which are associated with the Mandylion.

Shroud of Turin

Author Ian Wilson has argued that the object venerated as the Mandylion from the 6th to the 13th centuries was in fact the Shroud of Turin, folded in four, and enclosed in an oblong frame so that only the face was visible.[19] Wilson cites documents in the Vatican Library and the University of Leiden, Netherlands, which seem to suggest the presence of another image at Edessa. A 10th-century codex, Codex Vossianus Latinus Q 69,[20] found by Gino Zaninotto in the Vatican Library, contains an 8th-century account saying that an imprint of Christ's whole body was left on a canvas kept in a church in Edessa: it quotes a man called Smera in Constantinople: "King Abgar received a cloth on which one can see not only a face but the whole body" (Latin: [non tantum] faciei figuram sed totius corporis figuram cernere poteris).[21]

Holy Face of Genoa

This image is kept in the Church of St Bartholomew of The Armenians in Genoa, Italy. In the 14th century it was donated to the doge of Genoa Leonardo Montaldo by the Byzantine Emperor John V Palaeologus.

It has been the subject of a detailed 1969 study by Colette Dufour Bozzo, who dated the outer frame to the late 14th century,[22] giving a terminus ante quem for the inner frame and the image itself. Bozzo found that the image was imprinted on a cloth that had been pasted onto a wooden board.[23][24]

The similarity of the image with the Veil of Veronica suggests a link between the two traditions.

Holy Face of San Silvestro

This image was kept in Rome's church of San Silvestro in Capite, attached to a convent of Poor Clares, up to 1870, and is now kept in the Matilda chapel in the Vatican Palace. It is housed in a Baroque frame added by Sister Dionora Chiarucci, head of the convent, in 1623.[25] The earliest evidence of its existence is 1517, when the nuns were forbidden to exhibit it to avoid competition with the Veronica. Like the Genoa image, it is painted on board and therefore is likely to be a copy. It was exhibited at Germany's Expo 2000 in the pavilion of the Holy See.

-

The Holy Face of Genoa.

-

The Holy Face of Genoa with the face more visible.

-

The image from San Silvestro (Matilda chapel in the Vatican Palace).

-

The San Silvestro image with the face more visible.

Veil of Veronica

Historian Rebecca Rist says that devotion to Saint Veronica was encouraged by Pope Innocent III in part to compete with Constantinople's Mandylion and increase the prestige of Rome and its pope by claiming a similar acheiropoieta, the Veil of Veronica.[26][27]

In later Western European tradition the main likeness of the face of Jesus not made by human hand (i.e., an acheiropoieton), became the Veil of Veronica, supposedly the cloth offered by Saint Veronica to Jesus so he could wipe his face on the way to his crucifixion. That the name "Veronica" may derive from "true image" (alternatively pherenike ("bearer of blessing" in Greek), and the late appearance of this legend, has increased the scepticism of scholars.[28] A cloth believed to exist today in the Vatican is supposed to have been brought back to Italy at the time of the Crusades.[29] The Veil of Veronica (Latin: Sudarium, 'sweat-cloth'), often called simply "The Veronica" and known in Italian as the Volto Santo or Holy Face (but not to be confused with the carved crucifix the Volto Santo of Lucca), is a Christian relic of a piece of cloth which, according to tradition, bears the image of Jesus' face. Various existing images have been claimed to be the "original" relic, or early copies of it.[30]

Accounts of the Veil of Veronica and the Image of Edessa are sometimes confused by scholars.[31]

See also

- Abgar Legend: a Christian legend of an alleged correspondence and exchange of letters between Jesus Christ with King Abgar V Ukkāmā of Osroene.

- Acheiropoieta: sacred Christian images "not made by hands"

- Depiction of Jesus

- Keramidion: icon considered to be created by contact with the Image of Edessa

- Relics associated with Jesus

- Shroud of Turin

- Veil of Veronica, another "not made by hands" image of Christ

Citations

- ^ Guscin, Mark (2016-02-08). The Tradition of the Image of Edessa. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 9781443888752.

- ^ Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiae 1.13.5 and .22.

- ^ Steven Runciman, "Some Remarks on the Image of Edessa", Cambridge Historical Journal 3.3 (1931:238-252), p. 240

- ^ Runciman 1931, loc. cit..

- ^ Evagrius, in Migne, Patrologia Graecalxxxvi, 2, cols. 2748f, noted by Runciman 1931, p. 240, note 5; remarking that "the portrait of Christ has entered the class of αχειροποίητοι icons".

- ^ a b Two documentary inventories: year 1534 (Gerard of St. Quentin de l'Isle, Paris) and year 1740. See Grove Dictionary of Art, Steven Runciman, Some Remarks on the Image of Edessa, Cambridge Historical Journal 1931, and Shroud.com for a list of the group of relics. See also an image of the Gothic reliquary dating from the 13th century, in Histor.ws Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ of Caesarea, Eusebius. Church History, Book I Chapter 13. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Palmer, Andrew (Summer 1998). "A time for killing". Gouden Hoorn: A Journal of Byzantium. 6 (1). ISSN 0929-7820.

- ^ Kitzinger, 103–104, 103 with first quote; Procopius, Histories of the Wars, II, 26, 7–8, quoted, and 26–30 on Jesus' promise, Loeb translation quoted.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Changing Cultures in Early Byzantium. Variorum. p. 156. ISBN 9780860785873.

- ^ Kitzinger, 103

- ^ de Voragine, Jacobus (1275). The Golden Legend or Lives Of The Saints. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Stracke, Richard. Golden Legend: Life of SS. Simon and Jude. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Kedrenos, ed. Bekker, vol. I:685; see K. Weitzmann, "The Mandylion and Constantine Porphyrogennetos", Cahiers archéologiques 11 (1960:163-84), reprinted in Studies in Classical and Byzantine Manuscript Illumination, H. Kessler, ed. (Chicago, 1971:224-76).

- ^ John Scylitzes. 231f, noted in Holger A. Klein, "Sacred Relics and Imperial Ceremonies at the Great Palace of Constantinople", 2006:91 and note 80 ([ reprinted on-line]).

- ^ K. Weitzmann, The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Icons I: From the Sixth to the Tenth Century, Princeton, 1976:94-98, and plates xxxvi-xxxvii.

- ^ Archaeological Study Bible by Zondervan

- ^ The itinerario of Jeronimo Lobo, 1984, page 400

- ^ Wilson 1991

- ^ From the library of Gerhard Johann Vossius.

- ^ Codex Vossianus Latinus, Q69, and Vatican Library, Codex 5696, fol.35, which was published in Pietro Savio, Ricerche storiche sulla Santa Sindone Turin 1957.

- ^ Wilson 1991, p. 162

- ^ Wilson 1991, p. 88

- ^ Das Mandylion von Genua und sein paläologischer Rahmen - The Mandylion of Genoa Archived 2007-11-14 at the Wayback Machine (in German) See also: Annalen van de stad Genua uit de 14de eeuw beschrijven dat het de echte Edessa-mandylion betreft (in Dutch)

- ^ Wilson 1991, p. 193

- ^ Rist, Rebecca (2017). "Innocent III and the Roman Veronica: Papal PR or Eucharistic icon?". In Murphy, Amanda Clare; Kessler, Herbert L.; Petoletti, Marco; Duffy, Eamon; Milanese, Guido (eds.). The European fortune of the Roman Veronica in the middle ages. Convivium Supplementum. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. pp. 114–125. doi:10.1484/m.convisup-eb.5.131046. hdl:11222.digilib/137738. ISBN 978-80-210-8779-8. OCLC 1021182894.

- ^ Nicolotti, Andrea (2019). "The European Fortune of the Roman Veronica in the Middle Ages". Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture (Book review). 7 (1): 162–173, at p. 167.

- ^ Hall, 321

- ^ "St. Peter's - St Veronica Statue". stpetersbasilica.info. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Taylor, Joan E. (2018-02-08). What Did Jesus Look Like?. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-67151-6.

- ^ Nicolotti 2019, p. 171.

General and cited references

- Cameron, Averil. "The History of the Image of Edessa: The Telling of a Story." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 7 (Okeanos: Essays presented to Ihor Sevcenko on his Sixtieth Birthday by his Colleagues and Students) (1983): 80-94.

- Dufour Bozzo, Colette (1974), Il "Sacro Volto" di Genova (in Italian), Ist. Nazionale di Archeologia, ISBN 88-7275-074-1

- Eusebius of Caesarea. "Epistle of Jesus Christ to Abgarus King of Edessa". Historia Ecclesiae.

- Eisenman, Robert, 1997. James the Brother of Jesus. (Viking Penguin). In part a deconstruction of the legends surrounding Agbar/Abgar.

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Kitzinger, Ernst, "The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 8, (1954), pp. 83–150, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, JSTOR 1291064.

- Wilson, Ian (1991), Holy Faces, Secret Places, Garden City: Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-26105-5

- Westerson, Jeri (2008), Veil of Lies: A Medieval Noir, New York: Minotaur Books, ISBN 9780312580124 Fiction referencing the Mandyllon.

- Nicolotti, Andrea (2014), From the Mandylion of Edessa to the Shroud of Turin: The Metamorphosis and Manipulation of a Legend, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004269194

Further reading

- Ionescu-Berechet, Ştefan (2010). "Τὸ ἅγιον μανδήλιον: istoria unei tradiţii". Studii Teologice. 6 (2): 109–185.

External links

- Image: Mandylion of Genoa

- Old and new Images from Edessa

- Icons of the Mandylion (mostly Russian)

- Is the Shroud of Turin the Image of Edessa? Archived 2006-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Eyewitness report: The sermon of Gregory Referendarius in 944

- Documentary proofs, make out a list of sixteen documents in the period 944 to 1247

- The Templar Mandylion: Relations of a Breton Calvary with the Turin Shroud and the Templar Knights. Excerpt of an electronic publication.

- Shroud of Turin and the Mandylion - Full Story (François Gazay)