Leevi Madetoja

Leevi Madetoja | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 February 1887 |

| Died | 6 October 1947 (aged 60) Helsinki, Finland |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Leevi Antti Madetoja (pronounced [ˈleːʋi ˈmɑdetˌojɑ];[1] 17 February 1887 – 6 October 1947) was a Finnish composer, music critic, conductor, and teacher of the late-Romantic and early-modern periods. He is widely recognized as one of the most significant Finnish contemporaries of Jean Sibelius, under whom he studied privately from 1908 to 1910.

The core of Madetoja's oeuvre consists of a set of three symphonies (1916, 1918, and 1926), arguably the finest early-twentieth century additions to the symphonic canon of any Finnish composer, Sibelius excepted. As central to Madetoja's legacy is Pohjalaisia (The Ostrobothnians, 1923), proclaimed Finland's "national opera" following its successful 1924 premiere and, even today, a stalwart of the country's repertoire. Other notable works include an Elegia for strings (1909); Kuoleman puutarha (The Garden of Death, 1918–21), a three-movement suite for solo piano; the Japanisme ballet-pantomime, Okon Fuoko (1927); and, a second opera, Juha (1935). Madetoja's fourth symphony, purportedly lost in 1938 at a Paris railway station, never materialized.

Acclaimed during his lifetime, Madetoja today is seldom heard outside the Nordic countries, although his music has in recent decades enjoyed a renaissance, as the recording projects of a number of Nordic orchestras and conductors evidence. His idiom is notably introverted for a national Romantic composer, a blend of Finnish melancholy, folk melodies from his native region of Ostrobothnia, and the elegance and clarity of the French symphonic tradition, founded on César Franck and guided by Vincent d'Indy. His music also reveals Sibelius's influence.

Madetoja was also an influential music critic, primarily with the newspaper Helsingin sanomat (1916–32), in which he reviewed the music scenes of France and Finland, praising Sibelius in particular. In 1918, he married the Finnish poet L. Onerva; their marriage was tempestuous and remained childless. His health failing due to alcoholism, Madetoja died from a heart attack on 6 October 1947 in Helsinki.

Life and career

Early years (1887–1915)

Childhood

Madetoja was born in Oulu, Finland, on 17 February 1887, the third son of Anders Antinpoika Madetoja (1855–1888) and Anna Elisabeth, née Hyttinne (1858–1934).[2] To provide for his family, Madetoja's father, a first mate on a merchant ship,[3] had earlier emigrated in 1886 to the United States, only to die in 1888 of tuberculosis along the Mississippi River.[2] Leevi thus never met his father, and his mother raised him and his brother, Yrjö (1885–1918). (Madetoja's oldest brother, Hjalmar, had died as an infant in 1883.)[2] The family lived in poverty and struggled with hunger, and as a boy Leevi worked variously as a street cleaner and as a laborer at a sawmill.[4]

Although his first attempts at composition were at the age of eight, Madetoja was by no means a musical prodigy. He studied the violin and piano on his own and played the mouth organ as a boy. Additionally, Madetoja became a skilled kantele player: he received a 10-string kantele on his tenth birthday, and in secondary school at the Oulu Lyceum, he upgraded to a 30-string version. (Madetoja is certainly the only notable classical composer in history whose primary instrument was the kantele.)[2] At the Lyceum, Leevi sang in, and eventually directed, the school's male and mixed choirs.[5]

Student years

In 1906, Madetoja enrolled at the University of Helsinki and the Helsinki Music Institute, where he studied music theory, composition, and piano under Armas Järnefelt and Erik Furuhjelm.[6] A year later, in the summer of 1907, the Finnish Literature Society sponsored Madetoja's trip to the Inkeri region in Russia so that he could collect folk songs.[6] Additional good fortune arrived in 1908, when Jean Sibelius, Finland's most famous composer, accepted Leevi for private instruction. Although his lessons with Sibelius at Ainola were unstructured and sporadic, Madetoja valued his time with the master and assimilated some of Sibelius's unique idiom. The two studied together until 1910. (For more see: Madetoja and Sibelius.)

At the Music Institute, Madetoja's premiered his first compositions at student concerts: in December 1908, the Op. 2 songs, Yksin and Lähdettyäs; and on 29 May 1909, the Piano Trio, Op. 1 (second and third movements only).[6] His public introduction arrived in January 1910 when Robert Kajanus, chief conductor of the Helsinki Orchestral Society, conducted Madetoja's Elegia (from the four-movement Symphonic Suite, Op. 4) to great success; critics described the Elegia as the "first master work" of a budding "natural orchestral composer".[7]

After graduating from the Music Institute and the University of Helsinki in 1910, Madetoja took up a career as a music critic, penning essays and reviews for the Säveletär magazine and, later, the Päivä newspaper.[7] Additional praise followed Madetoja's first composition concert in Helsinki on 26 September 1910, at which he conducted the Piano Trio and excerpts from the Symphonic Suite and Chess, Op. 5 (excerpted from incidental music Madetoja had composed for Eino Leino's play).[7][n 1] The positive reviews did, however, contain a note of concern: given Madetoja's plans to travel to Paris for additional education, the critic Evert Katila of Uusi Suometar worried about the negative influence "French modern atonal composition" could have on "this fresh northern nature [Madetoja]".[7]

Madetoja's interest in the Paris music scene was a result of the enthusiastic reports of his composer-friend, Toivo Kuula, who had earlier studied in the city.[7] With funding from the Finnish government and a letter of introduction from Sibelius, Madetoja applied to be a student of Vincent d'Indy, who headed a school of thought founded upon the symphonic principles of César Franck. The two only met for one lesson, however, as d'Indy took ill and Madetoja's plans collapsed; he would spend the rest of his time in Paris without a teacher, attending concerts and working on his own compositions (the result was the Concert Overture, Op. 7).[7][8]

After a brief stay in Oulu (where he composed and premiered on 29 September 1911 a short cantata for mixed choir and piano, Merikoski, Op. 10), Madetoja undertook a second trip abroad, this time to Vienna and Berlin, in the autumn of 1911. Sibelius again aided his pupil, arranging for Madetoja to study under his former teacher, Robert Fuchs.[9][n 2] While in Vienna, Madetoja audited composition and conducting courses at the Conservatory, observed Franz Schalk's rehearsals,[8] and composed Dance Vision, Op. 11.[10]

Conductorships

In 1912, Kajanus appointed Madetoja and Kuula—who had together returned to Helsinki from Berlin—as assistant conductors of the Helsinki Orchestral Society, Madetoja's term lasting until 1914. The appointment put Madetoja in the middle of Helsinki's "orchestra feud", as Kajanus' Orchestral Society squared off against Georg Schnéevoigt's newly created Helsinki Symphony Orchestra, which consisted mainly of foreign musicians.[10][11][n 3] Madetoja's position with the Orchestral Society provided him the opportunity to perform a number of his compositions: on 12 October 1912, Dance Vision premiered under Madetoja's baton, and even more importantly, he had his second composing concert on 14 October 1913, where he premiered the Concert Overture and Kullervo, Op. 15, a symphonic poem based on the Kalevalic tragic hero of the same name.[n 4] Madetoja earned little as an assistant conductor and thus supplemented his income as a music critic for Uusi Suometar, becoming well known for his articles on the French music scene and his recurring travels to Paris.[10]

The dawn of the First World War in July 1914 brought an end to the feud between the two rival orchestras: the Helsinki Symphony Orchestra collapsed after the German musicians who formed its backbone were expelled from the country, and Kajanus and Schnéevoigt divided conducting duties for a joint orchestra, the Helsinki City Orchestra, that consisted of forty players surviving on starvation wages.[14] The merger rendered Madetoja (and, a year later, Kuula) superfluous, and Madetoja pawned his metronome to stave off penury.[8] Despite the hostilities, he traveled to Russia in September 1914 to take up the conductorship of the Viipuri Orchestra (1914–1916).[10] Madetoja found the group in a state of devastation: he was able to piece together 19 musicians, a reality that forced him to spend much of his time finding and arranging material for such an undersized ensemble.[15]

Mature career (1916–1930)

A new Finnish symphonist

While juggling his responsibilities in Viipuri, Madetoja worked on his most first major compositions, the First Symphony in Helsinki (Kajanus the dedicatee), conducting the premiere on 10 February 1916; apparently he completed the finale just before this performance.[7] The critics, some of whom—for example Karl Wasenius in Hufvudstadsbladet—noted the influence of Sibelius, received the work warmly.[16] Buoyed by this success, Madetoja relocated to Helsinki and began composing a second symphony in the summer. To support himself, he began work as a music critic for the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper (1916–32) and as a teacher of music theory and history at the Music Institute (1916–39).[n 5] In 1917, the Finnish government granted Madetoja a three-year artist's pension, which allowed him to focus more on composing. (In 1918, the pension was extended for life.)[15]

In 1918, the embers of the First World War ignited into civil war (27 January – 15 May 1918) between socialist Red Guards and the nationalist Whites. The war brought personal tragedy to Madetoja: On 9 April, Red Guards captured and executed Yrjö Madetoja, Leevi's brother, during the Battle of Antrea in Kavantsaari. It fell to Leevi to inform his mother:

I received a telegram from Viipuri yesterday that made my blood run cold: "Yjrö fell on the 13th day of April" was the message in all its terrible brevity. This unforeseen, shocking news fills us with unutterable grief. Death, that cruel companion of war and persecution, has not therefore spared us either; it has come to visit us, to snatch one of us as its victim. Oh when will we see the day when the forces of hatred vanish from the world and the good spirits of peace can return to heal the wounds inflicted by suffering and misery?

— Leevi Madetoja, in a 5 May 1916 letter to his mother, Anna[17]

A month later, during May Day celebrations, Kuula got into an altercation with a group of White Army officers, one of whom shot him to death.[18] These two losses deeply upset Madetoja and likely found expression in the symphony, a composition in which he had already been contemplating Finland's fate in the wake of world war and a revolution in Russia; the epilogue Madetoja affixed to the work is one of pain and resignation: "I have fought my battle and now withdraw".[18][n 6]

The 17 December 1918 premiere of the Second Symphony under Kajanus's baton was extraordinarily well received. Katila, for example, proclaimed Madetoja's latest work to be "the most remarkable achievement in our music since the monumental series of Sibelius".[22][n 7] (Upon his mother's death in 1934, Madetoja retroactively dedicated the Second Symphony to her.) Around this time, Madetoja also published in Lumikukkia magazine a piece for solo piano, originally titled Improvisation in Memory of my Brother Yrjö. In 1919, Madetoja expanded the piece into a three-movement suite, renaming it The Garden of Death, Op. 41, and removing the reference to his brother;[17] the suite shares melodic motifs with the Second Symphony.[3]

The 1920s found Madetoja financially stable but stretched thin. In addition to his teaching responsibilities at the Music Institute and criticism for Helsingin Sanomat, by June 1928 Madetoja had added the position of music teacher at his other alma mater, the University of Helsinki. Despite the trifling salary, the post held great prestige,[23] having previously been the chair of Fredrik Pacius (1835–69),[24] Richard Faltin (1870–96),[25] and (controversially) Kajanus (1897–27),[26] and included among its tasks the conductorship of the Academic Orchestra.[27] He also took on administrative roles in the music profession: in 1917, he was a founding member of the Finnish Composers' League (Suomen Säveltaiteilijain Liitto; forerunner to the Society of Finnish Composers, or Suomen Säveltäjät, founded in 1945), serving as its secretary and, later, president; in 1928, moreover, he helped establish the Finnish Composers' Copyright Society (Säveltäjäin Tekijänoikeustoimisto; TEOSTO), serving on its board of directors from 1928 to 1947 and as its chairman from 1937 to 1947.[27][28] Despite manifold commitments, Madetoja (somehow) found time to compose three of his most important, large-scale works: an opera, The Ostrobothnians, Op. 45 (1918–23); the Third Symphony, Op. 55 (1925–26); and a ballet-pantomime, Okon Fuoko, Op. 58 (1925–27). When taken together, these three works solidified his position as Finland's premiere, post-Sibelian composer.

A Finnish national opera

The Ostrobothnians commission, first offered to Kuula in November 1917, was for an opera based upon the popular 1914 folk play by the Ostrobothnian journalist and writer, Artturi Järviluoma. Although Kuula viewed the play as a strong candidate for a libretto, its realism conflicted with his personal preference for fairy tale or legend-based subject matter, in keeping with the Wagnerian operatic tradition.[citation needed] When Kuula refused the opportunity, the commission fell to Madetoja, who had also expressed interest in the project. The composition process, begun in late December 1917, took Madetoja much longer than expected; letters to his mother indicate that he had entertained hopes of completing the opera by the end of 1920 and, when this deadline passed, 1921 and, eventually, 1922. In the end, the opera was not completed until September 1923, although it would be another full year until the opera premiered.[citation needed] Nevertheless, some of the music (from Acts I and II)[29] did see the light of day sooner, as Madetoja had pieced together a five-number orchestral suite at the behest of Kajanus, who premiered the suite on 8 March 1923 in Bergen, Norway during his orchestra tour; the reviews were positive, describing the music as "interesting and strange".[2]

The first performance of the complete opera on 25 October 1924 at the Finnish National Opera (which, incidentally, was also the one-thousandth performance in the history of the Opera House) was, perhaps, the greatest triumph of Madetoja's entire career. Indeed, with The Ostrobothnians, Madetoja succeeded where his teacher, Jean Sibelius, famously had failed: in the creation of a Finnish national opera, a watershed moment for a country lacking an operatic tradition of its own.[30][n 8] In Helsingin sanomat, Katila wrote on behalf of many Finns, calling The Ostrobothnians "the most substantial work in the whole of Finnish opera".[30] The Ostrobothnians immediately became a fixture of the Finnish operatic repertoire (where it remains today), and was even produced abroad during Madetoja's lifetime, in Kiel, Germany in 1926; Stockholm in 1927; Gothenburg in 1930; and, Copenhagen in 1938.[30]

Two final masterworks

After the success of The Ostrobothnians, Madetoja departed for France, staying for six months in Houilles, a small town just outside of Paris. Here, in the quiet of the Parisian suburbs, Madetoja began to compose his Third Symphony, Op. 55, and upon returning to Finland in October (due to financial worries), his work on the project continued.[31] The new symphony received its premiere in Helsinki on 8 April 1926, and although Madetoja received the usual praise, the audience and critics found the new work somewhat perplexing: with the monumental, elegiac Second Symphony having set expectations, the optimism and restraint of the Third came as a surprise, its (subsequent) significance eluding nearly everyone. Some years later, the French music writer, Henri-Claude Fantapié, described the cheerful, pastorale Third Symphony as a "sinfonia Gallica" in spirit and explained the premiere as thus: "The listeners expected the opera [The Ostrobothnians] to be followed by a nationalistic anthem and were disappointed to hear something that seemed to them to be hermetic and that, to crown it all, was lacking in pomposity and solemnity … the properties the majority of Finnish music-lovers always expect in a new work."[31] Nevertheless, today the Third Symphony is widely regarded as Madetoja's "masterpiece", the rare Finnish symphony equal in stature to Sibelius's seven essays in the form.

While on his way to Paris in 1925, Madetoja had met a music publisher from Copenhagen, Wilhelm Hansen, who placed him into contact with the Danish playwright Poul Knudsen. A libretto for a new ballet-pantomime, based upon "exotic" Japanese themes, was on offer and Madetoja accepted the project with alacrity.[n 9] Having outlined his plan for the new commission while staying in Houilles, Madetoja he more or less composed the Third Symphony and Okon Fuoko simultaneously, although the pressure to complete the former was so great that Madetoja was compelled to place the ballet-pantomime aside until December 1926. Although Madetoja completed the score in late 1927, scheduling the ballet-pantomime's premiere in Copenhagen proved difficult, despite the enthusiasm of the chief conductor of the Royal Danish Orchestra, Georg Høeberg, who after a test rehearsal had proclaimed the score a "masterpiece".[33] The primary cause of the delay appears to have been the difficulty of casting a lead actor, as the part required both singing and miming; Knudsen insisted upon—and opted to wait for—an actor then on leave from the theatre, Johannes Poulsen.[34]

The production languished unperformed until it (finally) received its premiere on 12 February 1930, not in Copenhagen, but rather in Helsinki, at the Finnish National Opera under the baton of Martti Similä.[35] The performance was the first significant setback of Madetoja's career: although the critics "unanimously praised" Madetoja's music, the consensus opinion was that Knudsen's libretto—with its awkward mixture of song, melodramatic spoken dialogue, dance, and pantomime—was a dramatic failure. In the end, Okon Fuoko received only three performances total and the Danish premiere never took place. Seeking to salvage his score, Madetoja in 1927 pieced together the six-number Okon Fuoko Suite No. 1, which proved a success; the composer's plans to set two additional suites never materialized.

Later years (1931–1947)

Declining fortunes

For Madetoja, the 1930s brought hardship and disappointment. During this time, he was at work on two new major projects: a second opera, Juha, and a fourth symphony, each to be his final labor in their respective genres. The former, with a libretto by the famous Finnish soprano, Aino Ackté (adapted from the 1911 novel by writer Juhani Aho),[36] had fallen to Madetoja after a series of events: first, Sibelius—ever the believer in "absolute music"—had refused the project in 1914;[37][n 10] and, second, in 1922, the Finnish National Opera had rejected a first attempt by Aarre Merikanto as "too Modernist" and "too demanding on the orchestra", leading the composer to withdraw the score.[39][n 11] Two failures in, Ackté thus turned to Madetoja, the successful The Ostrobothnians of whom was firmly ensconced in the repertoire, to produce a safer, more palatable version of the opera.[39]

The death of Madetoja's mother, Anna, on 26 March 1934, interrupted his work on the opera; the loss so devastated Madetoja that he fell ill and could not travel to Oulu for the funeral.[27][41][n 12] Madetoja completed work on the opera by the end of 1934 and it premiered to considerable fanfare at the Finnish National Opera on 17 February 1935, the composer's forty-eighth birthday. The critics hailed it as a "brilliant success", an "undisputed masterpiece of Madetoja and Finnish opera literature".[27] Nevertheless, the "euphoria" of the initial performance eventually wore off and, to the composer's disappointment, Juha did not equal the popularity of The Ostrobothnians. Indeed, today Juha is most associated with Merikanto, whose modernist Juha (first performed in the 1960s) is the more enduringly popular of the two; having been displaced by Merikanto's, Madetoja's Juha is rarely performed.[27][39]

The lost symphony

The composition of the Fourth Symphony remains a mystery, although Madetoja's chief biographer, Erkki Salmenhaara, has unearthed the key details. In the spring of 1930, Madetoja told Karjala newspaper that he had begun a new symphony with the themes derived from "Finnish folk song".[42] An eight-year gestation ensued. Plans to complete the symphony in time for his fiftieth birthday on 17 February 1937 did not come to fruition, and in July 1937, Madetoja retired to the spa town of Runni in Iisalmi to focus further on the symphony.[43] As the Fourth's finish line neared in the spring of 1938, Madetoja traveled to Nice hoping that France, as it had a decade earlier with the Third Symphony, would stoke his creative fires.[44]

Misfortune quickly dashed Madetoja's hopes: while passing through Paris on his way to Southern France, his suitcase—which contained the Fourth Symphony—was stolen at a railway station in the city; the near-completed manuscript was never recovered.[44] With his inspiration and memory in decline, Madetoja never undertook a reconstruction of the lost score, notwithstanding his (unsuccessful) 1941 application for a stipend to "finish my fourth symphony that is underway".[45] When a student of his, Olavi Pesonen, asked whether Madetoja could recreate the symphony, he replied, "Do you think that I could rewrite something that a thief has taken"?[44] By January 1942, he was hospitalized for alcoholism. During his treatment, Madetoja occupied himself with old issues of Musiikkitieto magazine and, when he came across a story about his time in Runni, he did not recall having composed the Fourth. ("I wonder if anything has been written at all"?)[46]

Death

In the 1940s, Madetoja battled poor physical health, depression, a collapsing marriage, and waning artistic inspiration; his already less-than-prolific pace declined to a crawl. During this time, Madetoja orchestrated his song cycle for soprano and piano, Autumn, Op. 68, a setting of his wife's poems he had completed eight years earlier. With its mature idiom and mournful outlook on the human experience, some sources describe Autumn as Madetoja's "testament".[citation needed] Otherwise, Madetoja occupied himself with smaller forms, primarily for choir a cappella; the seven Op. 81 songs for male choir were completed in 1946, as were the two Op. 82 songs for mixed choir. His final completed piece was Matkamies (Wayfarer) for female choir, written in the year of his death (sketch completed by Olavi Pesonen).

Madetoja died at approximately 11:00 am on 6 October 1947 at the Konkordia Methodist hospital in Helsinki.[47] Although some sources attribute his death to heart attack, no surviving record indicates a conclusive cause of death.[47] The Madetoja funeral took place five days later on 11 October at the Helsinki Old Church; the president of Finland, Juho Kusti Paasikivi, supplied a wreath, as did the Ministry of Education, the City of Oulu, and other institutions and mourners.[48] Critics praised Madetoja in obituaries and Onerva published a memorial poem.[citation needed][n 13] Madetoja left (very early) plans for a number of never-realized works, including a violin concerto, a requiem mass, a third opera (a "Finnish Parsifal"), and Ikävyys (Melancholy), a composition for voice and piano after Aleksis Kivi.[48]

Madetoja (joined by Onerva in 1972) is buried at Hietaniemi cemetery (Hietaniemen hautausmaa) in Helsinki, a national landmark and frequent tourist attraction that features the graves of famous Finnish military figures, politicians, and artists. Unveiled in 1955,[49] the gravestone—located on block V8 in the Old Area (Vanha alue), near the cemetery wall (circle marker 48 on the following map; approx. 60°10′04″N 024°54′59″E / 60.16778°N 24.91639°E)—is by the Finnish sculptor Kalervo Kallio and is courtesy of TEOSTO. Also buried in the cemetery are Madetoja's friend, Toivo Kuula (d. 1918; block U19), as well as Onerva's onetime paramour, Eino Leino (d. 1926; block U21).

Personal life

In February 1910, Madetoja—while composing the incidental music for Eino Leino's play, Chess—made the acquaintance of the Finnish poet Hilja Onerva Lehtinen (a.k.a., L. Onerva), a friend and lover of the playwright.[3][50] Although Madetoja was five years Onerva's junior, their relationship deepened and in 1913 they began telling others of their marriage;[51][n 14] in fact, however, they formally married in 1918.[52] Their financial situation precarious, an orchestral rehearsal in Turku doubled as honeymoon.[10] Their marriage was childless (even though they wished to have children)[53] and plagued by quarrels; each suffered from chronic alcoholism.[54] In the final years of Madetoja's life, Onerva was confined to a mental institution—it appears against her will, as the letters she wrote to her husband asking for him to retrieve her were not successful. In 2006, the couple's correspondence was published in Finnish under the title, Night Songs: L. Onerva and Leevi Madetoja's Letters from 1910 to 1946 (eds. Anna Makkonen and Tuurna Marja-Leena).

Relationship with Sibelius

Student and teacher

Madetoja, 22 years Sibelius's junior, began to study composition privately under the Finnish master in 1908, a unique opportunity with which only one other individual prior to Madetoja had been presented: his friend, Toivo Kuula.[55][n 15] Later in life, during Sibelius's fiftieth birthday celebrations, Madetoja recounted the way in which he had, as a young man, reacted to the news:

I still clearly remember with what real feeling of joy and respect I received the information that I had been accepted as a student of Sibelius—I thought I was seeing a beautiful dream. Jean Sibelius, that master blessed by the Lord, would be bothered to read the pieces written by me!

— Leevi Madetoja, in a December 1915 article for the Karjala newspaper[6]

Sibelius seems to have discounted his own pedagogical skills, telling Madetoja, "I am a bad teacher.".[56] First, he had little patience for pedagogy or the quotidian nature of instruction, resulting in a teaching style that was "too haphazard"[57] and "anything but systematic or disciplined".[3] This was not lost on Madetoja, who in January 1910 wrote to Kuula in Paris, "Sibelius has been tutoring me. You know from your own experience that his tutoring is anything but detailed."[57] Madetoja recalled, for example, that Sibelius's method consisted of "short, striking remarks" (for example, "No dead notes. Every note must live"), rather than "instruction in the ordinary pedagogic sense".[56]

Second, Sibelius's "deeply idiosyncratic" idiom was too "personal" to serve adequately as a "foundation" upon which to build a school of musical thought.[58][57] That Madetoja's own musical style shows the mark of Sibelius is a testament to the longer duration and greater depth of his instruction under Sibelius; Kuula, who only briefly studied with Sibelius, shows no such influence.[59] Finally, Sibelius—prone to periods of self-doubt and ever-concerned with his standing in artistic circles—was mistrustful of the next generation of composers, fearing one might displace him from his perch.[60] "Youth has a right to make its voice heard. One sees oneself as a father figure to them all", Sibelius confided to his diary. "[But] they don't give a damn about you. Perhaps with reason."[61]

Despite these issues, Madetoja found his instruction under Sibelius enriching and the two men enjoyed a "harmonious" relationship, notwithstanding occasional irritations.[59][62] Madetoja was clearly fond of his teacher and enjoyed Sibelius's counsel and company:

Are you coming to Paris soon? I would be very pleased if you did. I am very lonely here. And my spirits are often low, because I have not yet been able to settle down to work. But I hope to do so very soon when my appetite for composition returns … I want to thank you yet again for all the kindness and goodwill you have shown me. You have inspired my work; you have given a faltering youngster courage to set out on the right path, albeit a thorny path but one that leads to the sun-clad and richly coloured heights. I shall always feel deeply grateful to you for all that you have done.

— Leevi Madetoja, writing from Paris, in a 1910 letter to Sibelius[63]

Madetoja continued to feel this way throughout his life. A decade later, he sought to defend Sibelius against the (growing) conventional wisdom that he was a poor teacher around whom no appreciable school of thought had formed (unlike, for example, Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School).[57] In Aulos, a volume published on the occasion of Sibelius's sixtieth birthday in 1925, Madetoja argued for a more nuanced, less "superficial" definition of the word 'teacher' and recounted with fondness his personal experiences as one of Sibelius's pupils.[64]

Colleagues

Sibelius followed Madetoja's rise with the pride of a teacher. Early on he recognized his pupil's potential as a symphonic composer ("What you wrote about your symphonic business delights me exceedingly," Sibelius wrote to Madetoja. "I feel that you will achieve your greatest triumphs in that genre, for I consider that you have precisely the properties that make a symphonic composer. This is my firm belief."),[62] and the 10 February 1916 premiere of Madetoja's First Symphony found Sibelius's remarking on its beauty. The 17 December 1918 premiere of Madetoja's Second Symphony similarly impressed Sibelius, who was again in attendance.[65]

Nevertheless, Sibelius also eyed Madetoja's maturation somewhat wearily. For example, when some reviews of the First Symphony discerned within Madetoja's music the influence of Sibelius, he worried his former pupil might take offence at the comparison and mistook Madetoja's characteristic "melancholia" for "sulkiness".[16] Suddenly, Sibelius found Madetoja arrogant and watched with concern as he drew closer to Kajanus, with whom Sibelius had an on-again-off-again friendship/rivalry. "Met Madetoja, who—I'm sorry to say—has become pretty bumptious after his latest success," Sibelius fretted to his diary. "Kajanus smothers him with flattery and he hasn't the breeding to see it for what it is."[16] A second complication for the Madetoja-Sibelius relationship was the master's fear that his former pupil eventually might "supplant him in public esteem".[63] Certainly Madetoja's rise coincided with Sibelius's increasing sense of isolation:

Despite how my "stock", so to speak, has risen with the people, I feel completely uncertain about myself. I see how the young lift their heads—Madetoja higher than others—and I have to admire them, but my inner self needs more egotism and callousness than I am presently capable of. And my contemporaries are dying.

— Jean Sibelius, in a diary entry from 9 March 1916[66]

Madetoja was "scarcely aware" of Sibelius's private musings to his diary, and for his part, he continued as a critic and writer to champion actively his former teacher. In July 1914, for example, Madetoja praised Sibelius's tone poem, The Oceanides, writing in Uusi Suometar that rather than "repeat endlessly" the style of his previous works, Sibelius had yet again shown his penchant for "renewing himself musically … It is the sign of life … always forward, striving for new aims."[67] He also had kind words for Tapiola, describing it as "a beautiful work", and among others, Sibelius's Third,[68] Fourth,[69] and Fifth symphonies.[70]

Despite his conducting duties in Viipuri and the stress of composing his First Symphony, Madetoja sought to take on yet another commitment: to write the first Finnish language biography of Sibelius in honor of the master's fiftieth birthday in 1915.[n 16] Notwithstanding his initial misgivings, Sibelius consented to the project; certainly, he could not have found a biographer more sympathetic and sensitive than Madetoja.[71] The interviews at Ainola, however, came to nothing: to the embarrassment of both men, publishers were uninterested in the biography. As Madetoja wrote to Sibelius:

I have now received refusals from every publisher. For me this is totally incomprehensible. Things have come to a pretty poor state when our publishers are so cautious, and think only of their wretched balance sheets, when a project of this importance concerning our greatest composer is proposed. I hope, however, you won't be angry with me, even though I have troubled you so much over this project.

— Leevi Madetoja, in a 1915 letter to Sibelius[72]

As a result, the biography was abandoned and Madetoja settled for a piece in Helsingin sanomat in which he took other critics to task for having overlooked the "absolute, pure" qualities of Sibelius's music.[73] Sibelius outlived Madetoja by almost ten years.

Music

Idiom

Stylistically, Madetoja belongs to the national Romantic school,[5][62][74] along with Finnish contemporaries Armas Järnefelt, Robert Kajanus, Toivo Kuula, Erkki Melartin, Selim Palmgren, and Jean Sibelius;[75] with the exception of Okon Fuoko, Madetoja's music, darkly colored but tonal, is not particularly modernist in outlook, certainly not when compared directly with the outputs of Uuno Klami, Aarre Merikanto, Ernest Pingoud, and Väinö Raitio.[76] For a Romantic composer, however, Madetoja's music is notably "introverted",[5] avoiding the excesses characteristic of that art movement in favor of the "balance, clarity, refinement of expression, and technical polish" of classicism.[citation needed]

Stylistically, Madetoja's idiom is unique and deeply personal, a blend of three distinct musical ingredients: 1) Finnish nationalism, as evidenced by Madetoja's use of folk melody (especially from his native region, Ostrobothnia) and literary sources, such as the Kalevala; 2) the musical language of Sibelius, under whom Madetoja privately studied; and finally, 3) the "elegance" of the French symphonic tradition, founded on César Franck and formally organized by Vincent d'Indy as the Schola Cantorum de Paris. Madetoja and Kuula—having both studied in Paris—represent the first two significant Finnish composers to show the influence of French music. Nevertheless, the two friends would travel different paths: whereas Kuula adopted the language and techniques of the French Impressionists headed by Claude Debussy.

Notable works

In total, Madetoja's oeuvre comprises 82 works with opus numbers and about 40 without. While he composed in all genres, Madetoja was most productive—and found his greatest success—with the orchestra: symphonies, operas, cantatas, and orchestral miniatures all flowed from his pen;[77][78] indeed, for Salmenhaara, Madetoja's work in this genre places him "on a par with his European colleagues" as a composer for orchestra.[74] Curiously, he composed no concerti, although at various times in his career he hinted at plans for a violin concerto.[79] Madetoja was also an accomplished composer for voice, as his numerous choral pieces and songs for voice and piano evidence; he found less success with—and composed sparingly for—solo piano, The Garden of Death notwithstanding.[80] Finally, Madetoja wrote little for chamber ensemble after his student years,[80][77] although it is unclear if this was due to insufficient skill or waning interest in the genre.

Symphonies

The core of Madetoja's oeuvre is his set of three symphonies, perhaps the most significant contribution to the genre of Finnish national Romantic composers, post-Sibelius.[28][3] Each of Madetoja's symphonies is "unique and distinct", a testament to his "true talent for symphonic composition".[62] The First Symphony, although late-Romantic in style, carefully eschews the extravagance and overindulgence typical of debut efforts, placing it among the most "mature" and restrained of first symphonies. Accordingly, Madetoja's First, in F major, is most concentrated of his three essays in the form and, at three movements rather than the traditional four, it is also the shortest.[81][29] Madetoja's Second, in E-flat major is a dramatic "war symphony" in which the composer contemplates personal loss during the Civil War. It is Madetoja's longest and most elegiac symphony and, perhaps for this reason, it is also the most enduringly popular of the set.[82][83] Although in four movements, Madetoja links movement I to II and movement III to IV; moreover, the symphony also features solo oboe and horn in distanza (offstage) in movement II. The Third, in A major, is optimistic and pastorale in character, as well as "more restrained" than the Second, is today considered one of the finest symphonies in the Finnish orchestral canon, indeed a "masterpiece ... equal in stature" to Sibelius's seven essays in the form.[84][29] Although technically his penultimate symphonic composition (a fourth symphony was lost and thus never completed), the Third is would be Madetoja's final addition to the symphonic canon.

Operas and ballets

The success of The Ostrobothnians was due to a confluence of factors: the appeal of the music, tonal but darkly colored; the use of folk melodies (blended with Madetoja's own idiom) familiar to the audience; a libretto (also by Madetoja) based upon a well-known and beloved play; a story about freedom from oppression and self-determination, the allegorical qualities of which were particularly salient in a country that had recently emerged from a war for independence; and, the skillful combination of comedic and tragic elements. The introduction to Act I (No. 2: Prisoner's Song in the suite), for example, is based upon a famous Ostrobothnian folk song, Tuuli se taivutti koivun larvan (The Wind Bent the Birch), which was one of the 262 folk songs Kuula had collected during his travels and which made its way into Madetoja's nationalistic opera, becoming its signature leitmotif.[30] Relative to The Ostrobothnians, with Juha Madetoja takes a "more symphonic, refined" approach, one that eschews folk tunes, despite the nationalistic themes of the libretto.[39]

Other

Legacy

Reception and recordings

Acclaimed during his lifetime, Madetoja is today seldom heard outside the Nordic countries (the Elegia perhaps excepted). A few commentators, however, have described such neglect as unfortunate and undeserved,[3] as Madetoja is one of the most important post-Sibelian Finnish symphonists.[22] Part of this neglect is not unique to Madetoja: the titanic legacy of Sibelius has made it difficult for Finnish composers (especially his contemporaries), as a group, to gain much attention, and each has had to labor under his "dominating shadow".[85][86] However, with respect to the neglect of Madetoja in particular, something else might also be at play: Madetoja's eschewal of Romantic excess in favor of restraint, perhaps, has made him a tougher sell to audiences. According to one music critic:

Because Madetoja never makes any concessions to the listener, his music has not gained the position it deserves in the public's awareness. People are now beginning to open their ears to it. But that he deserves far greater attention, and that his music is both rare and precious and not simply a poor edition of the music of Sibelius—that is something they have not yet learnt.

— Ralf Parland, writing in 1945, about two years before Madetoja's death in 1947[3]

In recent decades, Madetoja has begun to enjoy the renaissance Parland foresaw, as the recording projects of numerous Nordic orchestras and conductors evidence. Petri Sakari and the Iceland Symphony Orchestra (Chandos, 1991–92) and John Storgårds and the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra (Ondine, 2012–13) have each recorded the symphonies and a few of the more famous orchestral miniatures. Arvo Volmer and the Oulu Symphony Orchestra (Alba Records, 1998–2006), the largest of the projects, has recorded nearly all of Madetoja's works for orchestra, featuring the world premiere recordings for many pieces, among them the complete Symphonic Suite, Op. 4 (as opposed to just the Elegia), the Chess Suite, Op. 5; Dance Vision, Op. 11; the Pastoral Suite, Op. 34; the Barcarola, Op. 67/2, and Rustic Scenes, Op. 77.[n 17] All three of Madetoja's stage works, furthermore, have now been recorded in their complete, unabridged form—two recordings of The Ostrobothnians (Finlandia, 1975: Jorma Panula and the Finnish National Opera Orchestra; and, Finlandia, 1998: Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra) and one each of Juha (Ondine, 1977: Jussi Julas and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra) and of Okon Fuoko (Alba, 2002: Volmer and the Oulu Symphony Orchestra).

Nordic vocalists, virtuosos, and ensembles have preserved many of Madetoja's non-orchestral pieces as well. In 2004, Mika Rannali and Alba teamed to record Madetoja's complete works for solo piano, while in 2001–02, Gabriel Suovanen and Helena Juntunen covered the complete lieder for solo voice and piano for Ondine (Gustav Djupsjöbacka, piano accompaniment). Madetoja's works (with opus numbers) for choir a cappella have also received systematic treatment; in the 1990s, the YL Male Voice Choir and Finlandia recorded (across three volumes) those for male choir, while in 2006–07, the Tapiola Chamber Choir and Alba tackled many of those for mixed choir. Despite these projects, a large portion of Madetoja's oeuvre nevertheless remains unrecorded, the most notable omissions being the cantatas, a few neglected pieces for voice and orchestra, and the handful of compositions for chamber ensemble.

Modern-day critics have received the Madetoja revival with enthusiasm. The American Record Guide's Tom Godell, for example, has applauded the recording efforts of both Volmer and Sakari, in particular praising Madetoja for his "beautiful, swirling rainbows of vivid [orchestral] color" and his "uncanny ability to instantly establish a mood or rapidly sketch vast, ice-covered landscapes".[87] Writing for the same magazine, William Trotter reviews Volmer's "absorbing" five-volume set, pronouncing Madetoja a "first-rate composer, touched sometimes with genius … who had to wait a long, long time before his work could emerge from under the dominating shadow of his teacher's [Sibelius's] seven symphonies".[86] Reviewing the Ondine song collection for Fanfare, Jerry Dubins notes music's nuanced emotional range, as Madetoja achieves "moments of soaring ecstasy and searing pain", but without recourse to "sentimental" or "cloying" ornamentation. "It is, quite simply", Dubins continues, "some of the most gorgeous song-writing I have encountered in a very long time".[88] Similarly, the American Record Guide's Carl Bauman has kind words for the Rannali interpretations of Madetoja's "carefully written and polished ... unique" solo piano miniatures, but in an echo of Parland, notes that Madetoja's "natural, unpretentious tone" means that "one has to listen carefully in order to fully appreciate Madetoja's genius".[89] A notable detractor in the sea of praise, however, has been Donald Vroon, chief editor of the American Record Guide. Arguing that Madetoja's three symphonies "reflect the influences of Sibelius—but … without his blazing inspiration", Vroon describes Madetoja's music as "bland" and "brooding … very Nordic, maybe written in winter when the sun is seldom seen". He concludes, "I can't imagine anyone being thrilled by them [the symphonies] or considering Madetoja a great discovery".[90]

Memorials

A number of buildings and streets in Finland bear Madetoja's name. In Oulu, Madetoja's hometown, the Oulu Symphony Orchestra has performed since 1983 in the Oulu Music Center's (Oulun musiikkikeskus) Madetoja Hall (Madetojan sali), located on Leevi Madetoja Street (Leevi Madetojan katu). A second landmark in the city, directly adjacent to the Music Center, is the Madetoja School of Music (Madetojan musiikkilukio), a special music high school founded in 1968 and renamed in the composer's honor in 1981.[91] Oulu is also home to a bronze statue of the composer (approx. 65°00′54″N 025°28′14″E / 65.01500°N 25.47056°E), which stands in a park near Oulu City Hall; the statue was unveiled in 1962 and is by the Finnish sculptor Aarre Aaltonen.[49] Finally, in addition to the Madetoja-Onerva gravesite, Helsinki boasts two streets named after the composer (Madetojanpolku and Madetojankuja), both of which are near an urban park (Pukinmäki).

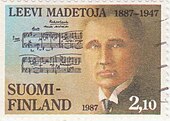

An additional honor arrived in 1987, when the Finnish government issued a postage stamp of Madetoja's likeness in commemoration of the centennial anniversary of the composer's birth. The centennial also marked the arrival of the Finnish musicologist Erkki Salmenhaara's Finnish-language biography of the composer, titled Leevi Madetoja (Helsinki: Tammi), which three decades later remains the definitive account of Madetoja's life and career. A year later in 1988, the Society of Finnish Composers established the Madetoja Prize for outstanding achievement in the performance of contemporary Finnish music; the Finnish conductor, Susanna Mälkki, is the current honoree (2016).[92]

In addition, every three years, the Oulu University of Applied Sciences (Oulun ammattikorkeakoulu) hosts—together with the Oulu Conservatory (Oulun konservatorion) and the Northern Ostrobothnia Association of Art and Culture (Pohjois-Pohjanmaan taiteen ja kulttuurin tuki ry)—the Leevi Madetoja Piano Competition (Leevi Madetoja pianokilpailu), which is one of Finland's premier music competitions for students. The Finnish Male Voice Choir Association (Suomen Mieskuoroliitto) is organizing quinquennial International Leevi Madetoja Male Voice Choir Competition, held for the first time in Turku in 1989. VII International Leevi Madetoja Male Voice Choir Competition will be organized at the Helsinki Music Centre on 10 April 2021.

Honors and titles

- 1910: Master of Arts, University of Helsinki

- 1910: Diploma in Composition, Helsinki Music Institute

- 1912–14: Assistant conductor, Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra (principal conductor: Robert Kajanus)

- 1914: Editor, Uusi Säveletär (music magazine)

- 1914–16: Conductor, Viipuri Music Society Orchestra

- 1916–39: Music teacher, Helsinki Music Institute (theory and history of music)

- 1916–32: Music critic, Helsingin sanomat (national daily newspaper)

- 1917: Founding member, Society of Finnish Composers

- 1917–47: Board member

- 1933–36: Chairman

- 1918–28: Secretary, State Commission of Music

- 1928–47: Committee member

- 1936–47: Chairman

- 1919: Grant recipient, State composer's pension

- 1926–39: Music teacher, University of Helsinki

- 1928–36: Lecturer

- 1937–47: Honorary Professor (more or less emeritus after 1939)

- 1928–47: Board member, Finnish Composers’ Copyright Society (TEOSTO)

- 1937–47: Chairman

- 1936: Grant recipient, 100th anniversary of the publication of the Kalevala grant

- 1947: Honorary award of the Finnish Cultural Foundation

- Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music

Notes, references, and sources

Notes

- ^ For example, Martin Wegelius, wrote in Helsingin Sanomat: "Rarely it is possible to return from a first-timer's concert with such great feelings of satisfaction. Indeed very few of us Finns are equipped with such extensive spiritual gifts, that he is able to 'break through' with those so quickly, to conquer the audience in only one evening. Leevi Madetoja did it yesterday and did it in a way which can only be called unique."[7]

- ^ According to Madetoja, Sibelius's reputation carried particular weight with Fuchs. Madetoja wrote to Sibelius on 9 November 1911: "Prof. Fuchs is very friendly towards me, and I immediately recognized that it is largely because of your recommendation."[9]

- ^ With 150,000 people, Helsinki could not sustain rival orchestras, especially with the Swedish-speaking patrons supporting Schnéevoigt and the Finnish-speakers backing Kajanus.[12]

- ^ Three other composers—Filip von Schantz, Kajanus, and Sibelius—had earlier tackled the subject of Kullervo. Certainly, the most famous is Sibelius's Op. 7 choral-symphony, written in 1892. Madetoja, however, could not have been familiar with his teacher's Kullervo, as Sibelius had withdrawn it in March 1893 after only a handful of performances.[13] Unlike Sibelius, who returned to the Kalevala for inspiration many times (e.g., the Lemminkäinen Suite, 1895; Pohjola's Daughter, 1906; Luonnotar, 1913; Tapiola, 1926, etc.), Kullervo represents Madetoja's lone attempt to set the Kalevala to music—or so many sources claim.[citation needed] However, Madetoja also composed two other tone poems based on Kalevalic themes: The Abduction of the Sampo, Op. 24 (1915), for baritone, male choir, and strings; and, Väinämöinen Sows the Wilderness, Op. 46 (1920), for soprano (or tenor) and orchestra.

- ^ Madetoja—quiet and unassuming by nature—was perhaps not the most charismatic of lecturers, but he was highly knowledgeable and had at his disposal a wealth of insightful observations gleaned from his own education and extensive travel.[15]

- ^ To honor his fallen friend, Madetoja wrote obituaries and, later, took it upon himself to complete four of Kuula's unfinished works, each of which he wished to remain exclusively attributed to Kuula:[19] a Stabat mater, for mixed chorus and orchestra; Karavaanikuoro (Choir of Caravan), Op. 21/1, adapted into a performing version for mixed chorus and orchestra;[20] Meren virsi (Song of the Sea), Op. 11/2, arranged for mixed chorus and orchestra (2222/4331/11/0/strings) and transposed down into (the more manageable key of) C-sharp minor (fp. 19 November 1920 by Suomen Laulu);[21] and, Virta venhettä vie (The Stream Carries the Boat'[citation needed] Madetoja also intended to author Kuula's biography with Toivo Tarvas, but the project never came to fruition.[19]

- ^ At the time, Sibelius had written five symphonies, although the Fifth Symphony had not yet reached its definitive form, which arrived in 1919.

- ^ The first notable Finnish opera was Fredrik Pacius's Kung Karls jakt (King Carl's Hunt) in 1852, after which followed a "long hiatus" until the rise of the national Romantic movement and "the desire to find an opera to reflect the burgeoning national values".[30] Certainly, the country did not lack for attempts at forging a "national opera": for example, Oskar Merikanto in 1898 with Pohjan neiti (Maiden of the North); Erkki Melartin in 1909 with the Wagnerian Aino; Selim Palmgren in 1910 with Daniel Hjort; Armas Launis in 1913 and 1917, respectively, with Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers) and Kullervo; and, Aarre Merikanto in 1922 with Juha. Nevertheless, each failed to capture the public's (lasting) attention.[30]

- ^ In fact, the libretto was first offered to Sibelius, who had earlier collaborated with Knudsen on the ballet-pantomime, Scaramouche, Op. 71. (1913; fp. 1922). Sibelius, however, was at the time deep into the composition of his Sixth Symphony and thus refused the project.[32]

- ^ According to Tawaststjerna, Ackté and Aho had first offered the libretto to Sibelius in November 1912, as Ackté had "felt confident that he [Sibelius] would produce something that was both powerful and refined".[38] Interested but noncommittal, Sibelius promised a firm answer within two years. To Ackté's disappointment, Sibelius declined the project in October 1914, finding its "rural verismo uncongenial"[38] and wishing to focus on his Fifth Symphony.[37]

- ^ According to Korhonen, while the 1920s featured the rise of Modernism in Finnish music, the national Romanticism was "still alive and well. Sibelius, Melartin, and Madetoja were at the height of their creative powers, and they were admired by the public at large". As such, many Modernist compositions were criticized by critics and a "hostile ... suspicious" public. Many others, were not even performed, "hidden in desk drawers".[40] Merikanto, an emerging modernist composer, likely received the Juha libretto from Ackté around 1920 and, after a "high state of inspiration", completed his score in the winter of 1921. After making revisions to the score in January 1922, Merikanto submitted the work to the board of the Finnish National Opera in the spring. Their rebuke stung Merikanto, and his Juha remained unperformed until 1963 in Lahti, five years after his death.[39]

- ^ In 1939, Madetoja published his Second Symphony (1918) using the inheritance money from his mother's death to cover the printing costs; as a tribute, he retroactively dedicated the work to her.[27][41]

- ^ Onerva's poem-obituary in honor of her husband reads, "And may the orchestra of your slumbers ring out like the music of the great, white future, that the buds of your dreams may unfold in mighty petals, the earth be lit with the golden rays of dawn—and that the songs may stream across the border to the great heart of humanity, transcend the moment, time, and generate the tune of eternity!"[citation needed]

- ^ In 1913, Onerva published her novel Inari, in which she utilized her own love-triangle as inspiration. In the book, Inari (Onerva) is a woman whose love wavers between two men, the artist Porkka (Leino) and the pianist Alvia (Madetoja).[50]

- ^ Sibelius later would take on Bengt de Törne as a third (and final) student. In 1958, De Törne published his reflections of Sibelius as a teacher in Sibelius: A Close-Up.

- ^ While staying at Lake Keitele in 1915, Madetoja wrote to Sibelius asking for his blessing: "Next Christmas—when you celebrate your fiftieth birthday—I plan to write a book about you and your musical achievements up to the present. Would you have any objections to this? Or would you not consider me suitable for such a task? I appreciate that this is a delicate matter—it would in fact be the very first attempt at the subject in the Finnish language, and I can assure you that I would try my very best to do justice to it."[71]

- ^ Finlandia (a subsidiary of Warner Classics) has also recorded Madetoja's complete symphonies, albeit with various composers and orchestras; as such, the Finlandia recordings do not constitute a "cycle" in the traditional sense of the term. Leif Segerstam and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra (1996) have recorded the First; Paavo Rautio and the Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra (1981) the Second; and Jorma Panula and the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra (1973) and Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the Finnish RSO (1993) each with the Third.

References

- ^ "Madetoja-nimen alkuperä" [Origin of the name Madetoja] (in Finnish). Madetojan musiikkilukio. 11 March 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Pulliainen (2000a), p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g Salmenhaara (2011)

- ^ Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 243–45

- ^ a b c Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 243

- ^ a b c d Pulliainen (2000b), p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pulliainen (2000b), p. 5

- ^ a b c Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 244

- ^ a b Mäkelä (2011), p. 71

- ^ a b c d e Pulliainen (2000c), p. 4

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 212–13, 231

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 231

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1976), p. 120–21

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 50

- ^ a b c Pulliainen (2000c), p. 5

- ^ a b c Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 81

- ^ a b Rännäli (2000), p. 6–7

- ^ a b Pulliainen (2000a), p. 6

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1987), p. 173

- ^ Mäntyjärvi & Mäntyjärvi (2010), p. 18

- ^ Tommila (2011), p. 22–23

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1992b), p. 5

- ^ Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 432–33

- ^ Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 292–94

- ^ Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 69

- ^ Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 159

- ^ a b c d e f Pulliainen (2001), p. 4

- ^ a b Hillila & Hong (1997), p. 245

- ^ a b c Salmenhaara (1992a)

- ^ a b c d e f Korhonen (2007), p. 60

- ^ a b Pulliainen (2001), p. 5

- ^ Rickards (1997), p. 160

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 245.

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 255.

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 260.

- ^ Pulliainen (2000a), p. 5

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 2

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 236

- ^ a b c d e Korhonen (2007), p. 70

- ^ Korhonen (2007), p. 63

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1987), p. 279

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 263

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 302–5

- ^ a b c Salmenhaara (1987), p. 305

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 320

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 321

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1987), p. 350

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1987), p. 351

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1987), p. 352

- ^ a b Nieminen 1982, p. 123.

- ^ Mäkelä 2003, pp. 283–84.

- ^ Mäkelä 2003, p. 399, 413.

- ^ Nieminen 1982, p. 171.

- ^ Mäkelä 2003, p. 575.

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 133

- ^ a b Ekman (1938), p. 141

- ^ a b c d Korhonen (2007), p. 47

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 132, 134

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 133–134

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 132–34

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 100

- ^ a b c d Korhonen (2013a), p. 4

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna (1986), p. 134

- ^ Ekman (1938), p. 139–42

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 140

- ^ Goss (2009), p. 351

- ^ Kilpeläinen (2012), p. x

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 111

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 179

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 93

- ^ a b Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 64–65

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 65

- ^ Tawaststjerna (1997), p. 69

- ^ a b Salmenhaara (1992b), p. 4

- ^ Korhonen (2007), p. 30–31, 34, 40–42, 46–49, 52, 56

- ^ Korhonen (2007), p. 64–66, 68–72

- ^ a b Korhonen (2007), p. 50

- ^ Karjalainen (1982), p. 15

- ^ Salmenhaara (1987), p. 297–98, 339

- ^ a b Karjalainen (1982), p. 16

- ^ Korhonen (2013a), p. 4–5

- ^ Korhonen (2013b), p. 5

- ^ Salmenhaara (1992b)

- ^ Korhonen (2013a), p. 5–6

- ^ Korhonen (2007), p. 46

- ^ a b Trotter (2006), p. 136–137

- ^ Godell (2001), p. 126–127

- ^ Dubins (2003), p. 173

- ^ Bauman (2006), p. 124

- ^ Vroon (2000), p. 176

- ^ Hautala (1982), p. 344–46

- ^ Suomen Säveltäjät (2015)

Sources

Books

- Ekman, Karl (1938). Jean Sibelius: His Life and Personality. (Edward Birse, English translation). New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (2009). Sibelius: A Composer's Life and the Awakening of Finland. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Hautala, Kustaa (1982). Oulun kaupungin historia, V (in Finnish). Oulu: Kirjapaino Oy Kaleva.

- Hillila, Ruth-Esther; Hong, Barbara Blanchard (1997). Historical Dictionary of Music and Musicians of Finland. London: Greenwood Press.

- Kilpeläinen, Kari (2012). "Introduction" (PDF). In Sibelius, Jean (ed.). Aallottaret : eine Tondichtung für großes Orchester (Early version) [op. 73]; Die Okeaniden - Aallottaret : eine Tondichtung für großes Orchester op. 73; Tapiola : Tondichtung für großes Orchester op. 112. ISMN 979-0-004-80322-6. OCLC 833823092. Complete Works (JSW) edited by the National Library of Finland and the Sibelius Society of Finland Series I (Orchestral works) Vol. 16: The Oceanides Op. 73 / Tapiola Op. 112 edited by Kari Kilpeläinen.

- Karjalainen, Kauko (1982). "Leevi Madetoja". In Pesonen, Olavi (ed.). Leevi Madetoja: Teokset (Leevi Madetoja: Works) (in Finnish and English). Helsinki: Suomen Säveltäjät (Society of Finnish Composers). ISBN 951-99388-4-2.

- Korhonen, Kimmo (2007). Inventing Finnish Music: Contemporary Composers from Medieval to Modern. Finnish Music Information Center (FIMIC). ISBN 978-952-5076-61-5.

- Mäkelä, Tomi (2011). Jean Sibelius. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd.

- Mäkelä, Hannu (2003). Nalle ja Moppe – Eino Leinon ja L. Onervan elämä [Nalle and Moppe – Life of Eino Leino and L. Onerva] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Otava. ISBN 951-1-18199-8.

- Nieminen, Reetta (1982). Elämän punainen päivä. L. Onerva 1882–1926 [Red Day of Life. L. Onerva 1882–1926] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 9517172907.

- Rickards, Guy (1997). Jean Sibelius. London: Phaidon. ISBN 9780714835815.

- Salmenhaara, Erkki (1987). Leevi Madetoja (in Finnish). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-30-6725-4.

- Salmenhaara, Erkki (2011). "Leevi Madetoja". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (Biographical Dictionary of the Republic of Finland) (in Swedish). Vol. M to Z (4 ed.). Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1976). Sibelius: Volume 1, 1865–1905. (Robert Layton, English translation). London: Faber and Faber.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1986). Sibelius: Volume 2, 1904–1914. (Robert Layton, English translation). London: Faber and Faber.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1997). Sibelius: Volume 3, 1914–1957. (Robert Layton, English translation). London: Faber and Faber.

CD liner notes

- Louhikko, Jouko (2005). Leevi Madetoja: Okon Fuoko, the Complete Ballet Pantomime Music (booklet). Arvo Volmer & Oulu Symphony Orchestra. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 21. ABCD 184.

- Korhonen, Kimmo (2013a). Leevi Madetoja: Symphony No. 1 and 3, Okon Fuoko Suite (booklet). John Storgårds & Helsinki Philharmonic. Helsinki, Finland: Ondine. p. 4–7. ODE1211-2.

- Korhonen, Kimmo (2013b). Leevi Madetoja: Symphony No. 2, Kullervo, Elegy (booklet). John Storgårds & Helsinki Philharmonic. Helsinki, Finland: Ondine. p. 4–6. ODE1212-2.

- Mäntyjärvi, Tuula; Mäntyjärvi, Jaakko (2010). Winter Apples: Finnish National Romantic Choral Music (booklet). Heikki Liimola & Klemetti Institute Chamber Choir. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 18. ABCD 329.

- Pulliainen, Riitta (2000a). Madetoja Orchestral Works 1: I Have Fought My Battle (booklet). Arvo Volmer & Oulu Symphony Orchestra. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 4–6. ABCD 132.

- Pulliainen, Riitta (2000b). Madetoja Orchestral Works 2: The Spirit Home of My Soul (booklet). Arvo Volmer & Oulu Symphony Orchestra. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 4–6. ABCD 144.

- Pulliainen, Riitta (2000c). Madetoja Orchestral Works 3: The Infinity of Fantasy (booklet). Arvo Volmer & Oulu Symphony Orchestra. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 4–6. ABCD 156.

- Pulliainen, Riitta (2001). Madetoja Orchestral Works 4: Laurel Wreaths (booklet). Arvo Volmer & Oulu Symphony Orchestra. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 4–8. ABCD 162.

- Rännäli, Mika (2000). Intimate Garden: Leevi Madetoja Complete Piano Works (booklet). Mika Rännäli. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 4–8. ABCD 206.

- Salmenhaara, Erkki (1992a). Madetoja, L.: Symphony No. 3, The Ostrobothnians Suite, Okon Fuoko Suite (booklet). Petri Sakari & Iceland Symphony Orchestra. Colchester, England: Chandos. p. 4–7. CHAN 9036.

- Salmenhaara, Erkki (1992b). Madetoja, L.: Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 (booklet). Petri Sakari & Iceland Symphony Orchestra. Colchester, England: Chandos. p. 4–6. CHAN 9115.

- Tommila, Tero (2011). Toivo Kuula – Legends 2 (booklet). Timo Lehtovaara & Chorus Cathedralis Aboensis, Petri Sakari & Turku Philharmonic Orchestra. Tampere, Finland: Alba. p. 22–23. ABCD 326.

Journal articles

- Bauman, Carl (2006). "Madetoja: Piano Pieces, all". American Record Guide. 69 (2): 124. (subscription required)

- Dubins, Jerry (2003). "Madetoja: Lieder...". Fanfare. 27 (2): 172–73. (subscription required)

- Godell, Tom (2001). "Madetoja: Symphony 1; Concert Overture; Pastoral Suite; Rustic Scenes". American Record Guide. 64 (2): 126–27. (subscription required)

- Trotter, William (2006). "Madetoja: Kullervo Overture; Vainamoinen Sows the Wilderness; Little Suite; Autumn; Okon-Fuoko Suite 2". American Record Guide. 69 (6): 136–37. (subscription required)

- Vroon, Donald (2000). "Madetoja: Symphonies (3) with Comedy Overture; Okon Fuoko Suite; Ostrobothnians Suite". American Record Guide. 63 (6): 176. (subscription required)

Websites

- Korhonen, Kimmo. "Leevi Madetoja in Profile". madetoja.org/en. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Suomen Säveltäjät (2015). "Madetoja-palkinto kapellimestari Susanna Mälkille". composers.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 10 July 2016.

External links

- 1887 births

- 1947 deaths

- Musicians from Oulu

- People from Oulu Province (Grand Duchy of Finland)

- Finnish opera composers

- Finnish male opera composers

- Composers for piano

- 20th-century Finnish classical composers

- Finnish music critics

- Pupils of Jean Sibelius

- Pupils of Robert Fuchs

- Pupils of Vincent d'Indy

- Burials at Hietaniemi Cemetery

- 20th-century Finnish male musicians