Mercury Theatre

Poster for the Mercury Theatre's three spring 1938 productions—Caesar, The Shoemaker's Holiday and The Cradle Will Rock—running simultaneously in two Broadway theaters | |

| Formation | August 1937 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1946 |

| Type | Theatre group |

| Location | |

Artistic director(s) | Orson Welles |

Notable members |

|

The Mercury Theatre was an independent repertory theatre company founded in New York City in 1937 by Orson Welles and producer John Houseman. The company produced theatrical presentations, radio programs and motion pictures. The Mercury also released promptbooks and phonographic recordings of four Shakespeare works for use in schools.

After a series of acclaimed Broadway productions, the Mercury Theatre progressed into its most popular incarnation as The Mercury Theatre on the Air. The radio series included one of the most notable and infamous radio broadcasts of all time, "The War of the Worlds", broadcast October 30, 1938. The Mercury Theatre on the Air produced live radio dramas in 1938–1940 and again briefly in 1946.

In addition to Welles, the Mercury players included Ray Collins, Joseph Cotten, George Coulouris, Martin Gabel, Norman Lloyd, Agnes Moorehead, Paul Stewart, and Everett Sloane. Much of the troupe would later appear in Welles's films at RKO, particularly Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons.

Theatre

Part of the Works Progress Administration, the Federal Theatre Project (1935–39) was a New Deal program to fund theatre and other live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States during the Great Depression.[1] In 1935, John Houseman, director of the Negro Theatre Unit in New York, invited his recent collaborator, 20-year-old Orson Welles, to join the project.[2]: 80 Their first production was an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Macbeth with an entirely African-American cast. It became known as the Voodoo Macbeth because Welles changed the setting to a mythical island suggesting the Haitian court of King Henri Christophe,[3]: 179–180 with Haitian vodou fulfilling the rôle of Scottish witchcraft.[4]: 86 The play opened April 14, 1936, at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem and was received rapturously.[5]

That production was followed by an adaptation of the farce Horse Eats Hat[6]: 334 and, in 1937, Marlowe's Doctor Faustus[6]: 335 and Marc Blitzstein's socialist musical The Cradle Will Rock. The latter received much publicity when on the eve of its preview the theatre was padlocked by the WPA. Welles invited the waiting audience to walk several blocks to a neighboring theatre where the show was performed without sets or costumes. Blitzstein played a battered upright piano while the cast, barred from taking the stage by their union, sat in the audience and rose from their seats to sing and deliver their dialogue.[6]: 337–338

Welles and Houseman broke with the Federal Theatre Project in August 1937 and founded their own repertory company, which they called the Mercury Theatre. The name was inspired by the title of the iconoclastic magazine, The American Mercury.[2]: 119–120

"All the Mercury offerings bore the credit line, 'Production by Orson Welles,'" wrote critic Richard France, "implying that he functioned not only as the director, but as designer, dramatist, and, most often, principal actor as well. To be sure, this generated a good bit of resentment among his collaborators (the designers, in particular). However, in a more profound sense, that credit is, in fact, the only accurate description of a Welles production. The concepts that animated each of them originated with him and, moreover, were executed in such a way as to be subject to his absolute control."[7]: 54

Welles and Houseman secured the Comedy Theatre, a 687-seat Broadway theatre[8]: 286 at 110 West 41st Street in New York City, and reopened it as the Mercury Theatre. It was the venue for virtually all their productions from November 1937 through November 1938.[9]

Caesar (1937–38)

The Mercury Theatre began with a groundbreaking, critically acclaimed adaption of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar that evoked comparison to contemporary Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. It premiered on Broadway on November 11, 1937.[10]: 339 [11]

The production moved from the Mercury Theatre to the larger National Theatre on January 24, 1938.[6]: 341 It ran through May 28, 1938, for a total of 157 performances.[12]

The cast included Joseph Holland (Julius Caesar), George Coulouris (Marcus Antonius), Joseph Cotten (Publius), Martin Gabel (Cassius), Hiram Sherman (Casca), John A. Willard (Trebonius), Grover Burgess (Ligarius), John Hoysradt (Decius Brutus), Stefan Schnabel (Metellus Cimber), Elliott Reid (Cinna), William Mowry (Flavius), William Alland (Marullus), George Duthie (Artemidorus), Norman Lloyd (Cinna, the poet), Arthur Anderson (Lucius), Evelyn Allen (Calpurnia, wife to Caesar), Muriel Brassler (Portia, wife to Brutus),[7]: 186 and John Berry (extra).[8]: 324 At the National Theatre, Polly Rowles took the role of Calpurnia and Alice Frost played Portia.[13]

From January 20, 1938, a roadshow version of Caesar with a different cast toured the United States. The company included Tom Powers as Brutus, and Edmond O'Brien as Marc Antony.[6]: 341

The Shoemaker's Holiday (1938)

The Mercury Theatre's second production was a staging of Thomas Dekker's Elizabethan comedy The Shoemaker's Holiday, which attracted "unanimous raves again". It premiered on January 1, 1938, and ran to 64 performances in repertory with Caesar, until April 1. It then moved to the National Theatre through April 28.[10]: 340–341

Heartbreak House (1938)

The first season of the Mercury Theatre concluded with George Bernard Shaw's Heartbreak House, which again attracted strong reviews. It premiered April 29, 1938, at the Mercury Theatre and ran for six weeks, closing June 11. Shaw insisted that none of the text be altered or cut, resulting in a longer and more conventional production that limited Welles's creative expression. It was chosen to demonstrate that the Mercury's style did not depend upon extensive revision and elaborate staging.[14]: 47–50

Geraldine Fitzgerald, a fellow member of the Gate Theatre company while Welles was in Dublin, was brought over from Ireland for her American debut as Ellie Dunn.[15][16]: 51 Welles played the octogenarian Captain Shotover. Other cast were Brenda Forbes (Nurse Guinness), Phyllis Joyce (Lady Utterword), Mady Christians (Hesione Hushabye), Erskine Sanford (Mazzini Dunn), Vincent Price (Hector Hushabye), John Hoysradt (Randall Utterword) and Eustace Wyatt (The Burglar)[17]

Too Much Johnson (1938)

The fourth Mercury Theatre play was planned to be a staging of Too Much Johnson, an 1894 comedy by William Gillette. The production is now remembered for Welles's filmed sequences, one of his earliest films. There were to be three sequences: a 20-minute introduction, and 10-minute sequences transitioning into the second and third acts.[18]: 118

The production was meant to be a summer show on Broadway in 1938, but technical problems (the Mercury Theatre in New York was not yet adequately equipped to project the film segments) meant that it had to be postponed. It was due to run in repertory with Danton's Death in the fall of 1938, but after that production suffered from numerous budgetary over-runs, a New York run of Too Much Johnson was abandoned altogether. The play ran for a two-week trial at the Stony Creek Summer Theatre, Stony Creek, Connecticut, from August 16, 1938, in a scaled-back version which never made use of the filmed sequences.[7]: 142–143, 187–188 [10]: 344–345

Long considered lost, the footage for Too Much Johnson was rediscovered in 2013.[19]

Danton's Death (1938)

A production of Georg Büchner 1835 play Danton's Death, about the French Revolution, was the next Mercury stage production. It opened on November 2, 1938, but met with limited success and only ran to 21 performances,[20] closing November 19.[21] The commercial failure of this play forced the Mercury to significantly scale back on the number of plays planned for their 1938–39 season.[10]: 347 Danton's Death was the last Mercury production at the Mercury Theatre, which had been leased until 1942. The company relinquished the theatre in June 1939.[22]

Five Kings (Part One) (1939)

The final full-length Mercury production before the troupe headed to Hollywood in 1939 was Five Kings (Part One). This was an entirely original play by Welles about Sir John Falstaff, which was created by mixing and re-arranging dialogue from five different Shakespeare plays (primarily taken from Henry IV, Part I, Henry IV, Part II, and Henry V, but also using elements of Richard II and The Merry Wives of Windsor), to form a wholly new narrative. It opened on February 27, 1939, at the Colonial Theatre, Boston, in a five-hour version playing from 8pm to 1am. As the title suggests, the play was intended to be the first of a two-part production, but although it opened in three other cities, poor box-office receipts meant that plan had to be abandoned, and Five Kings (Part One) never played in New York, while Five Kings (Part Two) was never produced at all.[10]: 350–351

Five Kings was an intensely personal project for Welles, who would revive a substantially rewritten version of the play (retitled Chimes at Midnight) in Belfast and Dublin in 1960, and would eventually make a film of it, which he came to regard as his favourite of his own films.

The Green Goddess (1939)

In July and August 1939, after having signed a contract with the RKO film studio, the Mercury Theatre toured the RKO Vaudeville Theatre circuit with an abbreviated, twenty-minute production of the William Archer melodrama The Green Goddess, five minutes of which took the form of a film insert. The show was performed as often as four times a day.[10]: 353

Native Son (1941)

The Mercury Theatre had moved to Hollywood late in 1939, after Welles signed a film contract which would eventually result in his debut, Citizen Kane, in 1941. In the intervening period, the troupe focused on their radio show, which had begun in 1938 and continued until March 1940. Their last full play after moving to Hollywood was a stage adaptation of Richard Wright's anti-racism novel Native Son. It opened at the St. James's Theatre, New York, on March 24, 1941 (just a month before Citizen Kane premiered), and received excellent reviews, running to 114 performances. This was the final Mercury production which Welles and Houseman collaborated upon.[10]: 362

"The Mercury Theatre was killed by lack of funds and our subsequent move to Hollywood," Welles told friend and mentor Roger Hill in a conversation June 20, 1983. "All of the money I had made on radio was spent on the Mercury, but I didn't make enough money to finance the entire operation. Hollywood was really the only choice. … I think all acting companies have a lifespan. My partnership with John Houseman came to an end with the move to California. He became my employee, expensive and not particularly pleasant or productive. Our mutual discomfort led to his decamping California and returning to New York."[23]: 88

The Mercury Wonder Show (1943)

Although the Mercury troupe technically dissolved either in 1941 (when Welles and Houseman parted) or 1942 (when the entire Mercury unit was sacked by RKO - see below), Welles produced and directed this morale-boosting variety show for US troops in 1943, featuring a number of Mercury actors including Joseph Cotten and Agnes Moorehead. The show was based in a 2,000-seater tent on Cahuenga Boulevard, Hollywood, where it ran for a month from August 3, 1943, before touring nationwide.[10]: 177–180, 377–378

Gallery

-

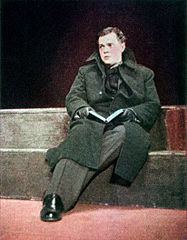

Brutus (Orson Welles) in Caesar

-

Standing over the murdered body of Caesar, Brutus (Orson Welles) is confronted by Marc Antony (George Coulouris) and Cassius (Martin Gabel) in Caesar

-

Portia (Alice Frost) and Brutus (Orson Welles) in Caesar

-

Marc Blitzstein, Howard da Silva and Olive Stanton in The Cradle Will Rock

-

Cast of the Mercury Theatre presentation of The Cradle Will Rock

-

Hiram Sherman in The Shoemaker's Holiday

-

Cast and set of The Shoemaker's Holiday

Radio

The Mercury Theatre on the Air (1938)

By 1938, Orson Welles had already worked extensively in radio drama, becoming a regular on The March of Time, directing a seven-part adaptation of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, and playing the title character in The Shadow for a year, as well as a number of uncredited character roles.

After the theatrical successes of the Mercury Theatre, CBS Radio invited Welles to create a summer show. The series began on July 11, 1938, with the formula that Welles would play the lead in each show. .[24]

Welles insisted his Mercury company — actors and crew — be involved in the radio series. This was an unprecedented and expensive request, especially for one so young as Welles. Most episodes dramatized works of classic and contemporary literature. It remains perhaps the most highly regarded radio drama anthology series ever broadcast, most likely due to the creativity of Orson Welles.

The Mercury Theatre on the Air was an hour-long program. Houseman wrote the early scripts for the series, turning the job over to Howard E. Koch at the beginning of October. Music for the program was composed and conducted by Bernard Herrmann. Their first radio production was Bram Stoker's Dracula, with Welles playing both Count Dracula and Doctor Seward. Other adaptations included Treasure Island, The Thirty-Nine Steps, The Man Who Was Thursday and The Count of Monte Cristo.

Originally scheduled for nine weeks, the network extended the run into the autumn, moving the show from its Monday night slot, where it was the summer substitute for the Lux Radio Theater, to a Sunday night slot opposite Edgar Bergen's popular variety show.

The early dramas in the series were praised by critics, but ratings were low. A single broadcast changed the program's ratings: the October 30, 1938 adaptation of H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds. Possibly thousands of listeners thought Martians were in fact invading the earth, due to the faux-news quality of most of the broadcast. Significant publicity was generated, and The Mercury Theatre on the Air quickly became one of radio's top-rated shows. The notoriety of "The 'War of the Worlds" had a welcome side effect of netting the show the sponsorship of Campbell's Soup, guaranteeing its survival for a period, and beginning on December 9, 1938, the show was retitled The Campbell Playhouse.

The Campbell Playhouse (1938–1940)

The Mercury Theatre continued broadcasting 60-minute episodes in 1938–40, now sponsored by Campbell's Soup and punctuated by commercials. The company moved to Hollywood for their second season, and Hollywood stars began to be featured in guest roles. The programme was billed as "The Campbell Playhouse presents the Mercury Theatre". A full list of the 56 episodes can be found at The Campbell Playhouse.

The Campbell Playhouse briefly continued after Welles's final performance in March 1940, with a truncated third season broadcast thereafter without the Mercury Theatre, but it was not a success.

The Mercury Summer Theatre of the Air (1946)

The Mercury troupe had disbanded by the time Welles made this series, commonly known as The Mercury Summer Theatre, in the summer of 1946. Nonetheless, it carried the Mercury name, was produced, written, directed and presented by Welles (and often starred or co-starred him), and it combined abridged scriptings of old Mercury performances with new shows. Occasionally, former members of the troupe would guest star in the 30-minute program. The series had limited success, it only lasted 15 episodes, and it was not renewed for a further season.

Film

Move to Hollywood

Orson Welles's notoriety following "The War of the Worlds" broadcast earned him Hollywood's interest, and RKO studio head George J. Schaefer's unusual contract. Welles made a deal with Schaefer on July 21, 1939, to produce, direct, write, and act in three feature films. (The number of films was later changed - see below.) The studio had to approve the story and the budget if it exceeded $500,000. Welles was allowed to develop the story without interference, cast his own actors and crew members, and have the privilege of final cut, unheard of at the time for a first-time director. (Welles later claimed that nobody in Hollywood had enjoyed this level of artistic freedom since Erich von Stroheim in the early 1920s.)[25] Additionally, as part of his contract, he set up a "Mercury Unit" at RKO; containing most of the actors from the Mercury's theatre and radio productions, as well as numerous technicians, (such as composer Bernard Herrmann), who were brought in from New York. Few of them had any film experience.

Welles spent the first five months of his RKO contract learning the basics of making films, and trying to get several projects going with no success. The Hollywood Reporter said, "They are laying bets over on the RKO lot that the Orson Welles deal will end up without Orson ever doing a picture there." First, Welles tried to adapt Heart of Darkness, but there was concern over the idea to depict it entirely with point of view shots, as Welles was unable to come up with an acceptable budget. Welles then considered adapting Cecil Day-Lewis' novel The Smiler with the Knife, but realized that this relatively straightforward pulp thriller was unlikely to make much impact for his film debut. He concluded that to challenge himself with a new medium, he had to write an original story.

Citizen Kane (1941)

As Welles decided on an original screenplay for his first film, he settled on a treatment he wrote, entitled American. In its first draft, it was only partially based on William Randolph Hearst, and also incorporated aspects of other tycoons such as Howard Hughes. However, American was heavily overlength, and Welles soon realized he would need an experienced co-writer to help redraft it—preferably one with experience of working with tycoons.

In 1940, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz was a former Hearst journalist recuperating from a car accident, and was in between jobs. He had originally been hired by Welles to work on The Campbell Playhouse radio program and was available to work on the screenplay for Welles's film. The writer had only received two screenplay credits between 1935 and his work on Citizen Kane and needed the job, his reputation having plummeted after he descended into alcoholism in the late 1930s. In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a dispute amongst historians regarding whose idea it was to use William Randolph Hearst as the basis for Charles Foster Kane. For some time, Mankiewicz had wanted to write a screenplay about a public figure, perhaps a gangster, whose story would be told by the people that knew him. Welles claimed it was his idea to write about Hearst, while film critic Pauline Kael (in her widely publicised 1971 essay "Raising Kane") and Welles's former business partner John Houseman claim that it was Mankiewicz's idea. Kael further claimed that Welles had written nothing of the original script, and did not deserve a co-writer credit. However, in 1985, film historian Robert Carringer showed that Kael had only reached her conclusion by comparing the first and last drafts of the Citizen Kane script, whereas Carringer examined every intermediate draft by Mankiewicz and Welles, and concluded that a co-writer credit was justified, with each man writing between 40% and 60% of the script. He additionally concluded that Houseman's claims to have contributed to the script were largely unfounded.[26]

Mankiewicz had already written an unperformed play entitled, The Tree Will Grow about John Dillinger. Welles liked the idea of multiple viewpoints but was not interested in playing Dillinger. Mankiewicz and Welles talked about picking someone else to use a model. They hit on the idea of using Hearst as their central character. Mankiewicz had frequented Hearst's parties until his alcoholism got him barred. The writer resented this and became obsessed with Hearst and Marion Davies. Hearst had great influence and the power to retaliate within Hollywood so Welles had Mankiewicz work on the script outside of the city. Because of the writer's drinking problem, Houseman went along to provide assistance and make sure that he stayed focused. Welles also sought inspiration from Howard Hughes and Samuel Insull (who built an opera house for his girlfriend). Although Mankiewicz and Houseman got on well with Welles, they incorporated some of his traits into Kane, such as his temper.

During production, Citizen Kane was referred to as "RKO 281". Filming took place between June 29, 1940, and October 23, 1940, in what is now Stage 19 on the Paramount Pictures lot in Hollywood, and came in under schedule. Welles prevented studio executives of RKO from visiting the set. He understood their desire to control projects and he knew they were expecting him to do an exciting film that would correspond to his "The War of the Worlds" radio broadcast. Welles's RKO contract had given him complete control over the production of the film when he signed on with the studio, something that he never again was allowed to exercise when making motion pictures. According to an RKO cost sheet from May 1942, the film cost $839,727 compared to an estimated budget of $723,800.

When the film was released, pressure from William Randolph Hearst led to many cinemas refusing to screen it, and it was screened in so few places that RKO made a substantial loss on the film on its original release. As a consequence of this, Welles's RKO contract was renegotiated, and he lost the right to control a film's final cut—something which would have major consequences for his next film, The Magnificent Ambersons.

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

Welles's follow-up to Citizen Kane was an adaptation of Booth Tarkington's novel The Magnificent Ambersons, a childhood favorite of his which he had already adapted for the radio. It portrayed the decline and fall of a proud Midwestern American family of the 19th century, as the motor car in the 20th century makes them obsolete.

Welles's relations with RKO grew strained during the making of this film. His stock had fallen considerably after Kane had commercially flopped. Whereas studio head George Schaefer had given Welles carte blanche over Kane, he closely supervised Ambersons, sensing that his own position was in danger (which indeed it was - Schaefer was fired as head of RKO shortly after Ambersons was completed, and a commonly-attributed reason was for his having hired Welles with such a generous contract). RKO itself was in serious financial trouble, running a deficit.

Welles himself considered his original cut of The Magnificent Ambersons to have been one of his finest films - "it was a much better picture than Kane". However, RKO panicked over a lukewarm preview screening in Pomona, California, when the film ran second in a double-bill with a romantic comedy. Around 55% of the audience strongly disliked the film (although the surviving audience feedback cards show that the remaining minority gave fulsome praise, using words such as "masterpiece" and "cinematic art"). Welles was in Brazil filming It's All True (see below), so the studio decided to trim over 40 minutes of the film's two-hour running time.

The first half of the film, portraying the happy times of the Ambersons in the 19th century, was largely unaffected. However, the vast majority of the second half of the film, portraying the Ambersons' fall from grace, was largely discarded as too depressing. Actors were drafted in for reshoots by other directors, who shot new scenes, including an upbeat, optimistic ending out of key with the rest of the film. The discarded 40 minutes of scenes by Welles were burned, and detailed, telegraphed instructions from him suggesting further compromises to save the film were thrown away, unread. This truncated version of The Magnificent Ambersons had a limited released in two Los Angeles cinemas in July 1942, where it did indifferently, and like Citizen Kane, the film lost RKO hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Later in 1942, George Schaefer was dismissed as studio head. One of the first changes initiated by his successor, Charles Koerner, was to fire Welles from RKO, and his entire Mercury unit was removed from the studio and closed down.

Journey into Fear (1943) and It's All True (1942-1993)

Welles's RKO contract was renegotiated after the commercial failure of Citizen Kane. Instead of delivering three major "A-pictures" for the studio, Welles would instead deliver two, and would compensate for the high costs of Citizen Kane by delivering two further films with lower budgets.

One of these was the straightforward espionage thriller Journey into Fear, based on a novel by Eric Ambler. Welles wrote and produced the film, but opted not to be the main director, not least as the film was on a tight schedule, filming back-to-back with The Magnificent Ambersons. The project appealed to RKO, especially as it seemed to be a low-risk, low-budget film.

The other project was first suggested by David Rockefeller, and since Welles was qualified as medically unfit for war service, it was suggested he could render service to the war effort by making a film to encourage Pan-American sentiment, since the US State Department was worried about fascist sympathies in some Latin American countries. The film's concept was loosely defined as an anthology of stories about different Americans being united against fascism, and it was hoped that a Pan-American song-and-dance number could be recorded. In February 1942, Brazil's carnival season was rapidly approaching, so it was decided to quickly send Welles over with technicolour cameras to film the carnival, and he could decide how to use the film later.

Studio director Norman Foster was heavily involved in both projects. Officially, he was the sole director of Journey into Fear. However, studio documentation and photographs show Welles directing that film (often in costume for his supporting role as "Colonel Haki"), and fuelled by amphetamines, he was directing Ambersons in the day and Journey at night. He finished his Journey scenes in the small hours of the morning he left for Brazil, and Foster directed the rest of the film to Welles's specific instructions. RKO found Journey into Fear too eccentric in its original form, and kept the film for a year before releasing it in 1943, by which time they had cut over twenty minutes. As with Ambersons, the excised footage was burned.

While Welles was in Brazil, he sent Foster to Mexico to direct one of the sequences of It's All True (based on the short story "My Friend Bonito", about a boy and his donkey), while he began to develop the rest of the film. As well as working his carnival footage into a sequence on the history of Samba, he filmed a sequence called "Four raftmen", about an epic sea voyage undertaken by Jangedeiros fishermen to seek justice from Brazil's president.

RKO rapidly turned against Welles and the It's All True project. Film historian Catherine Benamou has argued, based on extensive work in the RKO archives, that racism was a major underlying factor, and that RKO was alarmed that Welles was choosing to make non-white Americans the heroes of his story.[27] As well as ignoring his instructions while the studio recut Ambersons and Journey, they began issuing press releases attacking him for profligacy with studio funds, and accusing him of wasting his time in Brazil by attending lavish parties and drinking into the small hours (which he did - but fortified by amphetamines, he would also be the first to report for filming at 6am).[28] When a filming accident resulted in one actor drowning, RKO cited this as an example of Welles's irresponsibility. Finally, they ordered him to abandon the film. Not wishing to leave, Welles remained in Brazil with a skeleton crew which he funded himself, but eventually had to return when he ran out of film and RKO refused to send him any more.

After Welles was sacked in 1942, RKO had no plans for the It's All True footage. Some of it was dumped in the Pacific Ocean. Welles tried to buy back the negative, convinced he could fashion It's All True into a commercially successful film about samba, and he wrote the studio an "IOU" note for it, but when he could not afford the first installment on payments, the footage reverted to the studio. The footage was long presumed lost (though some of it was found again in 1985 and incorporated into a partial restoration in 1993), and Welles was unable to find a directing job for over three years, and even then, only for a formulaic low-budget thriller. In the meantime, the Mercury Theatre had disbanded for good.

Later cinema

The Mercury Theatre production team of John Houseman and Orson Welles separated during the making of Citizen Kane, but as the RKO Mercury unit retained its name until its removal from the studio in 1942. Since the Mercury Theatre name was not trademarked, Welles continued to use it for some of his subsequent projects, including The Mercury Wonder Show (a 1943 variety show), the 1946 musical Around the World (developed in collaboration with Cole Porter) and the 1946 radio series The Mercury Summer Theatre.

The final project undertaken under the Mercury Productions imprimatur was Welles' 1948 Republic Pictures adaptation of Macbeth, a distinction it retained upon its heavily edited (yet atypically profitable) 1950 rerelease; in a subtle nod to the febrile milieu that spawned the 1936 stage adaptation, several members of the Mercury Theatre repertory company (including Erskine Sanford, William Alland and Edgar Barrier) starred alongside Welles in the film.

Mercury Theatre actors in Welles's films

Welles cast a number of regular Mercury Theatre actors in his later films. Unless otherwise noted, information in this table is taken from Orson Welles at Work (2008) by Jean-Pierre Berthomé and Francois Thomas.[29]

| Actor | Theatre | Radio (1938–40) |

Cinema |

|---|---|---|---|

| William Alland | Caesar, The Shoemaker's Holiday, Danton's Death, Five Kings, The Green Goddess | 34 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, The Lady From Shanghai, Macbeth, F for Fake |

| Edgar Barrier | Too Much Johnson, Danton's Death, Five Kings | 32 broadcasts | Journey into Fear, Macbeth |

| Ray Collins | Native Son | 60 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Touch of Evil |

| Joseph Cotten | Caesar, The Shoemaker's Holiday, Too Much Johnson, Danton's Death, The Mercury Wonder Show | 11 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Journey into Fear, Othello, Touch of Evil, F for Fake |

| George Coulouris | Caesar, The Shoemaker's Holiday, Heartbreak House | 22 broadcasts | Citizen Kane |

| Agnes Moorehead | The Mercury Wonder Show | 21 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Journey into Fear |

| Frank Readick | None | 28 broadcasts | Journey into Fear |

| Erskine Sanford | Heartbreak House, Too Much Johnson, Danton's Death, Five Kings, Native Son | 4 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, The Stranger, The Lady From Shanghai, Macbeth |

| Stefan Schnabel | Caesar, The Shoemaker's Holiday | 4 broadcasts | Journey into Fear |

| Everett Sloane | Native Son | 40 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, Journey into Fear, The Lady From Shanghai |

| Paul Stewart | Native Son, The Mercury Wonder Show[6]: 377 [30]: 171 | 10 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, F for Fake, The Other Side of the Wind |

| Richard Wilson | The Shoemaker's Holiday, Too Much Johnson, Danton's Death, Five Kings | 31 broadcasts | Citizen Kane, The Lady From Shanghai, F for Fake, The Other Side of the Wind |

| Eustace Wyatt | Heartbreak House, Too Much Johnson, Danton's Death, Five Kings | 21 broadcasts | Journey into Fear |

Publishing and recording

One book was released under the Mercury Theatre imprint, with accompanying sets of records:

- Orson Welles and Roger Hill, The Mercury Shakespeare (Harper and Row, New York, 1939)

This was in fact a revised omnibus version of three volumes released in 1934 under the umbrella title of Everybody's Shakespeare, published by the 19-year-old Welles and his former school teacher & lifelong friend Roger Hill, by the Todd Press, the imprint of the Todd School for Boys where Welles was a pupil and Hill became Headmaster. The book contained "acting versions" (i.e. abridgments) of Julius Caesar, Twelfth Night and The Merchant of Venice. Accompanying the book, the Mercury Theatre released three sets of specially-recorded 12-inch 78-RPM gramophone records of these plays. Each of the three plays filled up 11, 10 and 12 records respectively.[31]

In addition to this, a great number of Mercury Theatre on the Air and Campbell Playhouse radio plays were subsequently turned into records, tapes and CDs, in many cases decades after their broadcast. For full details, see Orson Welles discography.

See also

References

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

- ^ Flanagan, Hallie (1965). Arena: The History of the Federal Theatre. New York: Benjamin Blom, reprint edition [1940]. OCLC 855945294.

- ^ a b Brady, Frank, Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1989 ISBN 0-684-18982-8

- ^ Hill, Anthony D. (2009). The A to Z of African American Theater. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. ISBN 9780810870611.

- ^ Kliman, Bernice W. (1992). Macbeth. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719027314.

- ^ Callow, Simon (1995). Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu. Penguin. p. 145. ISBN 0-670-86722-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1992). This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ a b c France, Richard (1977). The Theatre of Orson Welles. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 0-8387-1972-4.

- ^ a b Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21034-3.

- ^ "Artef Theatre". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jonathan Rosenbaum, "Welles's Career: A Chronology", in Jonathan Rosenbaum (ed.), Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992 [rev. 1998 ed.]

- ^ "Julius Caesar". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ^ "News of the Stage; 'Julius Caesar' Closes Tonight". The New York Times. May 28, 1938. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ The Playbill for the National Theatre production beginning Monday, March 14, 1938 (pp. 16–17)

- ^ Wood, Bret, Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0-313-26538-0

- ^ Lyman, Rick (July 19, 2005). "Geraldine Fitzgerald, 91, Star of Stage and Film, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ Lloyd, Norman (1993) [1990]. Stages of Life in Theatre, Film and Television. New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 9780879101664.

- ^ "Heartbreak House". Playbill, May 2, 1938. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ Higham, Charles, Orson Welles: The Rise and Fall of an American Genius. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1985 ISBN 0-312-31280-6

- ^ Kehr, Dave (August 7, 2013), "Early Film by Orson Welles Is Rediscovered", New York Times

- ^ "Danton's Death". Playbill. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "News of the Stage". The New York Times. November 18, 1938. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "Houseman, Welles Quit at Mercury". The New York Times. June 16, 1939. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Tarbox, Todd, Orson Welles and Roger Hill: A Friendship in Three Acts. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media, 2013, ISBN 1-59393-260-X.

- ^ "An Interview with John Houseman," Orson Welles on the Air: The Radio Years. New York: The Museum of Broadcasting, catalogue for exhibition October 28–December 3, 1988, page 12

- ^ Arena: Orson Welles interview with Leslie Megahey, Episode 1 (1982)

- ^ Robert L. Carringer, The Making of Citizen Kane (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1985)

- ^ Catherine Benamou, It's All True: Orson Welles's Pan-American Odyssey (University of California Press, Berkeley, California, 2007)

- ^ Interview in It's All True (film), 1993 documentary

- ^ Berthomé, Jean-Paul; Thomas, François (2008). Orson Welles at Work. London: Phaidon. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780714845838.

- ^ Whaley, Barton, Orson Welles: The Man Who Was Magic. Lybrary.com, 2005, ASIN B005HEHQ7E

- ^ Jonathan Rosenbaum (ed.), Peter Bogdanovich and Orson Welles, This is Orson Welles (DaCapo Press, New York, 1992 [rev. 1998 ed.]) p.348-9

External links

- The Mercury Theatre on the Air

- Mercury Theatre on the Air in the Internet Archive's Old-Time Radio Collection

- Mercury Radio Theater discography at Discogs

- Orson Welles And The Mercury Theater On The Air discography at Discogs

- Members Of The Mercury Theater discography at Discogs