Pentrich

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

| Pentrich | |

|---|---|

Pentrich Church | |

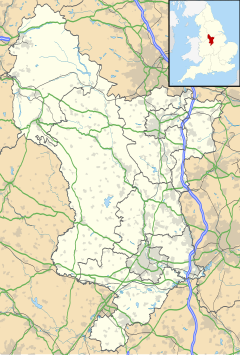

Location within Derbyshire | |

| Population | 191 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SK389525 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | RIPLEY |

| Postcode district | DE5 |

| Dialling code | 01773 |

| Police | Derbyshire |

| Fire | Derbyshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Pentrich is a small village and civil parish between Belper and Alfreton in Amber Valley, Derbyshire, England. The population at the 2011 Census was 191.[1]

Pentrich rising

The village gave its name to the Pentrich rising, an armed uprising which occurred on the night of 9-10 June 1817. While much of the planning took place in Pentrich, two of the three ringleaders were from South Wingfield and the other was from Sutton in Ashfield; the 'revolution' itself started from Hunt's Barn in South Wingfield, and the only person killed died in Wingfield Park.

A gathering of some two or three hundred men (stockingers, quarrymen and iron workers), led by Jeremiah Brandreth ('The Nottingham Captain'), (an unemployed stockinger, and claimed, without substantiation, by Gyles Brandreth as an ancestor), set out from South Wingfield to march to Nottingham. They were lightly armed with pikes, scythes and a few guns, which had been hidden in a quarry in Wingfield Park, and had a set of rather unfocussed revolutionary demands, including the wiping out of the National Debt.

The organizer of the event[citation needed] turned out to be a government spy, who became known as Oliver the Spy, and the uprising was quashed soon after it began.[2] Three men were hanged for their participation in the uprising, including Brandreth.[3]

St Matthew's Church

Whilst St Matthew's Church[4] is not mentioned in the Domesday book (1086), a charter of 1154–9 confirms the gift of the church of Pentrich to the canons of Darley Abbey. Of this Norman church or one which shortly after replaced it the five arcades separating the aisles from the nave, parts of the west wall and south aisle and lower part of the tower remain.

The tower was made higher in the late 14th century and the two aisles were rebuilt. Around 1430 a new pointed chancel arch was built, retaining the earlier capitals and piers and a clerestory was added. The tracery of the east window suggests a date of 1420–50.

The font stands on a pedestal dated 1662 but the bowl has decoration typical of the Norman period. During the 19th century the bowl was absent and was used for the salting of beef.

On the exterior of the south chancel wall is a scratch dial or mass clock, a sort of sundial used to show service times.

In literature

Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote the pamphlet "We Pity the Plumage, But Forget the Dying Bird" (1817) contrasting the wretched fate of the 'Pentrich Martyrs' (Brandreth, Turner & Ludlam) to the public mourning for the death of Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales in childbirth a day earlier.

Charles Lamb wrote "The Three Graves" (1820) (which turns out to be not for the condemned men, but their accusers)

- ...

- I ask'd the fiend, for whom these rites were meant?

- "These graves," quoth he, "when life's brief oil is spent,

- When the dark night comes, and they're sinking bedwards,

- I mean for Castles, Oliver, and Edwards."

- A fictional account is given of the postwar slump, chartism, the Pentrich Revolution and industrial progress in The Reckoning, Volume 15 of The Morland Dynasty, a series of historical novels by author Cynthia Harrod-Eagles.

Historical romance and erotic novelist Pam Rosenthal involves the hero and heroine of her novel The Slightest Provocation in the unmasking of the Pentrich uprising's government provocateur.

Paul and Clara visit the village in D. H. Lawrence's Sons and Lovers (Chapter 12). Although this is doubtful as he often used nearby placenames as substitutes for the actual location of his novels. Real Pentrich does not fit the context of this story as they walk to "Pentrich" from chapel in Eastwood, too far for an evening stroll. It is more likely Alma Hill near Kimberley with its "ruined windmill".[5]

See also

References

- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Sean Lang (2011). British History For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-470-74068-2.

- ^ John Cannon (4 July 2009). A Dictionary of British History. Oxford University Press. p. 1106. ISBN 978-0-19-955038-8. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ St Matthew's Church

- ^ A DH Lawrence Companion by F.B. Pinion Page 297

Bibliography

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2012) |

- Cooper, B (1983) Transformation of a Valley: The Derbyshire Derwent Heinemann, republished 1991 Cromford: Scarthin Books

- Cox, J C (1879) The Churches of Derbyshire Vol 4

- Pevsner, N (1978) The Buildings of England: Derbyshire