People's Liberation Army

| Chinese People's Liberation Army | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国人民解放军 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國人民解放軍 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "China People Liberation Army" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| People's Liberation Army |

|---|

|

| Executive departments |

| Staff |

| Services |

| Arms |

| Domestic troops |

| Special operations force |

| Military districts |

| History of the Chinese military |

| Military ranks of China |

|

|---|

|

|

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the military of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Republic of China (PRC). It consists of four services—Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force—and four arms—Aerospace Force, Cyberspace Force, Information Support Force, and Joint Logistics Support Force. It is led by the Central Military Commission (CMC) with its chairman as commander-in-chief.

The PLA can trace its origins during the Republican era to the left-wing units of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT) when they broke away in 1927 in an uprising against the nationalist government as the Chinese Red Army, before being reintegrated into the NRA as units of New Fourth Army and Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The two NRA communist units were reconstituted as the PLA in 1947.[9] Since 1949, the PLA has used nine different military strategies, which it calls "strategic guidelines". The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[10] Politically, the PLA and the paramilitary People's Armed Police (PAP) have the largest delegation in the National People's Congress (NPC); the joint delegation currently has 281 deputies—over 9% of the total—all of whom are CCP members.

The PLA is not a traditional nation-state military. It is a part, and the armed wing, of the CCP and controlled by the party, not by the state. The PLA's primary mission is the defense of the party and its interests. The PLA is the guarantor of the party's survival and rule, and the party prioritizes maintaining control and the loyalty of the PLA. According to Chinese law, the party has leadership over the armed forces and the CMC exercises supreme military command; the party and state CMCs are practically a single body by membership. Since 1989, the CCP general secretary has also been the CMC Chairman; this grants significant political power as the only member of the Politburo Standing Committee with direct responsibilities for the armed forces. The Ministry of National Defense has no command authority; it is the PLA's interface with state and foreign entities and insulates the PLA from external influence.

Today, the majority of military units around the country are assigned to one of five theatre commands by geographical location. The PLA is the world's largest military force (not including paramilitary or reserve forces) and has the second largest defence budget in the world. China's military expenditure was US$296 billion in 2023, accounting for 12 percent of the world's defence expenditures. It is also one of the fastest modernizing militaries in the world, and has been termed as a potential military superpower, with significant regional defence and rising global power projection capabilities.[11][12]: 259

In addition to wartime arrangements, the PLA is also involved in the peacetime operations of other components of the armed forces. This is particularly visible in maritime territorial disputes where the navy is heavily involved in the planning, coordination and execution of operations by the PAP's China Coast Guard.[13]

Mission

The PLA's primary mission is the defense of the CCP and its interests.[14] It is the guarantor of the party's survival and rule,[14][15] and the party prioritizes maintaining control and the loyalty of the PLA.[15]

In 2004, paramount leader Hu Jintao stated the mission of the PLA as:[16]

- The insurance of CCP leadership

- The protection of the sovereignty, territorial integrity, internal security and national development of the People's Republic of China

- Safeguarding the country's interests

- Maintaining and safeguarding world peace.

China describes its military posture as active defense, defined in a 2015 state white paper as "We will not attack unless we are attacked, but we will surely counterattack if attacked."[17]: 41

History

Early history

The CCP founded its military wing on 1 August 1927 during the Nanchang uprising, beginning the Chinese Civil War. Communist elements of the National Revolutionary Army rebelled under the leadership of Zhu De, He Long, Ye Jianying, Zhou Enlai, and other leftist elements of the Kuomintang (KMT), after the Shanghai massacre in 1927.[18] They were then known as the Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, or simply the Red Army.[19]

In 1934 and 1935, the Red Army survived several campaigns led against it by Chiang Kai-Shek's KMT and engaged in the Long March.[20]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War from 1937 to 1945, the CCP's military forces were nominally integrated into the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China forming two main units, the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army.[9] During this time, these two military groups primarily employed guerrilla tactics, generally avoiding large-scale battles with the Japanese, at the same time consolidating by recruiting KMT troops and paramilitary forces behind Japanese lines into their forces.[21]

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, the CCP continued to use the National Revolutionary Army unit structures until the decision was made in February 1947 to merge the Eighth Route Army and New Fourth Army, renaming the new million-strong force the People's Liberation Army (PLA).[9] The reorganization was completed by late 1948. The PLA eventually won the Chinese Civil War, establishing the People's Republic of China in 1949.[22] It then underwent a drastic reorganization, with the establishment of the Air Force leadership structure in November 1949, followed by the Navy leadership structure the following April.[23][24]

In 1950, the leadership structures of the artillery, armored troops, air defence troops, public security forces, and worker–soldier militias were also established. The chemical warfare defence forces, the railroad forces, the communications forces, and the strategic forces, as well as other separate forces (like engineering and construction, logistics and medical services), were established later on.

In this early period, the People's Liberation Army overwhelmingly consisted of peasants.[25] Its treatment of soldiers and officers was egalitarian[25] and formal ranks were not adopted until 1955.[26] As a result of its egalitarian organization, the early PLA overturned strict traditional hierarchies that governed the lives of peasants.[25] As sociologist Alessandro Russo summarizes, the peasant composition of the PLA hierarchy was a radical break with Chinese societal norms and "overturned the strict traditional hierarchies in unprecedented forms of egalitarianism[.]"[25]

In the PRC's early years, the PLA was a dominant foreign policy institution in the country.[27]: 17

Modernization and conflicts

During the 1950s, the PLA with Soviet assistance began to transform itself from a peasant army into a modern one.[28] Since 1949, China has used nine different military strategies, which the PLA calls "strategic guidelines". The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[10] Part of this process was the reorganization that created thirteen military regions in 1955.[citation needed]

In November 1950, some units of the PLA under the name of the People's Volunteer Army intervened in the Korean War as United Nations forces under General Douglas MacArthur approached the Yalu River.[29] Under the weight of this offensive, Chinese forces drove MacArthur's forces out of North Korea and captured Seoul, but were subsequently pushed back south of Pyongyang north of the 38th Parallel.[29] The war also catalyzed the rapid modernization of the PLAAF.[30]

In 1962, the PLA ground force also fought India in the Sino-Indian War.[31][32] In a series of border clashes in 1967 with Indian troops, the PLA suffered heavy numerical and tactical losses.[33][34][35]

Before the Cultural Revolution, military region commanders tended to remain in their posts for long periods. The longest-serving military region commanders were Xu Shiyou in the Nanjing Military Region (1954–74), Yang Dezhi in the Jinan Military Region (1958–74), Chen Xilian in the Shenyang Military Region (1959–73), and Han Xianchu in the Fuzhou Military Region (1960–74).[36]

In the early days of the Cultural Revolution, the PLA abandoned the use of the military ranks that it had adopted in 1955.[26]

The establishment of a professional military force equipped with modern weapons and doctrine was the last of the Four Modernizations announced by Zhou Enlai and supported by Deng Xiaoping.[37][38] In keeping with Deng's mandate to reform, the PLA has demobilized millions of men and women since 1978 and has introduced modern methods in such areas as recruitment and manpower, strategy, and education and training.[39] In 1979, the PLA fought Vietnam over a border skirmish in the Sino-Vietnamese War where both sides claimed victory.[40] However, western analysts agree that Vietnam handily outperformed the PLA.[36]

During the Sino-Soviet split, strained relations between China and the Soviet Union resulted in bloody border clashes and mutual backing of each other's adversaries.[41] China and Afghanistan had neutral relations with each other during the King's rule.[42] When the pro-Soviet Afghan Communists seized power in Afghanistan in 1978, relations between China and the Afghan communists quickly turned hostile.[43] The Afghan pro-Soviet communists supported China's enemies in Vietnam and blamed China for supporting Afghan anticommunist militants.[43] China responded to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by supporting the Afghan mujahidin and ramping up their military presence near Afghanistan in Xinjiang.[43] China acquired military equipment from the United States to defend itself from Soviet attacks.[44]

The PLA Ground Force trained and supported the Afghan Mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan War, moving its training camps for the mujahideen from Pakistan into China itself.[45] Hundreds of millions of dollars worth of anti-aircraft missiles, rocket launchers, and machine guns were given to the Mujahideen by the Chinese.[46] Chinese military advisors and army troops were also present with the Mujahideen during training.[44]

Since 1980

In 1981, the PLA conducted its largest military exercise in North China since the founding of the People's Republic.[10][47]

In the late 1980s, the central government had increasing expenditures and limited revenue.[48]: 43 The central government encouraged its agencies and encouraged local governments to expand their services and pursue revenues.[48]: 43 The PLA established businesses including hotels and restaurants.[48]: 43 The PLA gained more autonomy and permission to engage in commercial activities in exchange for a reduced role in political affairs and limited budgets;[49] the military was downsized to free resources for economic development.[50] The lack of oversight, ineffective self-regulation, and Jiang Zemin's and Hu Jintao's lack of close personal ties to the PLA,[49] led to systemic corruption that persisted through the late-2010s.[51] Jiang's attempt to divest the PLA of its commercial interests was only partly successful as many were still run by close associates of PLA officers.[49] Corruption lowered readiness and proficiency,[52] was a barrier to modernization and professionalization,[53] and eroded party control.[15] The 2010s anti-corruption campaigns and military reforms under Xi Jinping from the early-2010s were in part executed to address these problems.[54][55]

Following the PLA's suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, ideological correctness was temporarily revived as the dominant theme in Chinese military affairs.[56] Reform and modernization have today resumed their position as the PLA's primary objectives, although the armed forces' political loyalty to the CCP has remained a leading concern.[57][58]

Beginning in the 1980s, the PLA tried to transform itself from a land-based power centered on a vast ground force to a smaller, more mobile, high-tech one capable of mounting operations beyond its borders.[10] The motivation for this was that a massive land invasion by Russia was no longer seen as a major threat, and the new threats to China are seen to be a declaration of independence by Taiwan, possibly with assistance from the United States, or a confrontation over the Spratly Islands.[59]

In 1985, under the leadership of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the CMC, the PLA changed from being constantly prepared to "hit early, strike hard and to fight a nuclear war" to developing the military in an era of peace.[10] The PLA reoriented itself to modernization, improving its fighting ability, and becoming a world-class force. Deng Xiaoping stressed that the PLA needed to focus more on quality rather than on quantity.[59]

The decision of the Chinese government in 1985 to reduce the size of the military by one million was completed by 1987. Staffing in military leadership was cut by about 50 percent. During the Ninth Five Year Plan (1996–2000) the PLA was reduced by a further 500,000. The PLA had also been expected to be reduced by another 200,000 by 2005. The PLA has focused on increasing mechanization and informatization to be able to fight a high-intensity war.[59]

Former CMC chairman Jiang in 1990 called on the military to "meet political standards, be militarily competent, have a good working style, adhere strictly to discipline, and provide vigorous logistic support" (Chinese: 政治合格、军事过硬、作风优良、纪律严明、保障有力; pinyin: zhèngzhì hégé, jūnshì guòyìng, zuòfēng yōuliáng, jìlǜ yánmíng, bǎozhàng yǒulì).[60] The 1991 Gulf War provided the Chinese leadership with a stark realization that the PLA was an oversized, almost-obsolete force.[61][62] The USA's sending of two aircraft carrier groups to the vicinity of Taiwan during the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis prompted Jiang to order a ten-year PLA modernization program.[63]

The possibility of a militarized Japan has also been a continuous concern to the Chinese leadership since the late 1990s.[64] In addition, China's military leadership has been reacting to and learning from the successes and failures of the United States Armed Forces during the Kosovo War,[65] the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan,[66] the 2003 invasion of Iraq,[67] and the Iraqi insurgency.[67] All these lessons inspired China to transform the PLA from a military based on quantity to one based on quality. Chairman Jiang Zemin officially made a "revolution in military affairs" (RMA) part of the official national military strategy in 1993 to modernize the Chinese armed forces.[68]

A goal of the RMA is to transform the PLA into a force capable of winning what it calls "local wars under high-tech conditions" rather than a massive, numbers-dominated ground-type war.[68] Chinese military planners call for short decisive campaigns, limited in both their geographic scope and their political goals. In contrast to the past, more attention is given to reconnaissance, mobility, and deep reach. This new vision has shifted resources towards the navy and air force. The PLA is also actively preparing for space warfare and cyber-warfare.[69][70][71]

In 2002, the PLA began holding military exercises with militaries from other countries.[72]: 242 From 2018 to 2023, more than half of these exercises have focused on military training other than war, generally antipiracy or antiterrorism exercises involving combatting non-state actors.[72]: 242 In 2009, the PLA held its first military exercise in Africa, a humanitarian and medical training practice conducted in Gabon.[72]: 242

For the past 10 to 20 years, the PLA has acquired some advanced weapons systems from Russia, including Sovremenny class destroyers,[73] Sukhoi Su-27[74] and Sukhoi Su-30 aircraft,[75] and Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines.[76] It has also started to produce several new classes of destroyers and frigates including the Type 052D class guided-missile destroyer.[77][78] In addition, the PLAAF has designed its very own Chengdu J-10 fighter aircraft[79] and a new stealth fighter, the Chengdu J-20.[80] The PLA launched the new Jin class nuclear submarines on 3 December 2004 capable of launching nuclear warheads that could strike targets across the Pacific Ocean[81] and have three aircraft carriers, with the latest, the Fujian, launched in 2022.[82][83][84]

From 2014 to 2015, the PLA deployed 524 medical staff on a rotational basis to combat the Ebola virus outbreak in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau.[72]: 245 As of 2023, this was the PLA's largest medical assistance mission in another country.[72]: 245

China re-organized its military from 2015 to 2016. In 2015, the PLA formed new units including the PLA Ground Force, the PLA Rocket Force and the PLA Strategic Support Force.[85] In 2016, the CMC replaced the four traditional military departments with a number of new bodies.[86]: 288–289 China replaced its system of seven military regions with newly established Theater Commands: Northern, Southern, Western, Eastern, and Central.[86]: 289 In the prior system, operations were segmented by military branch and region.[86]: 289 In contrast, each Theater Command is intended to function as a unified entity with joint operations across different military branches.[86]: 289

The PLA on 1 August 2017 marked its 90th anniversary.[87] Before the big anniversary it mounted its biggest parade yet and the first outside of Beijing, held in the Zhurihe Training Base in the Northern Theater Command (within the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region).[88]

In December 2023, Reuters reported a military leadership purge after high-ranking generals were ousted from the National People's Congress.[89] Prior to 2017, over sixty generals were investigated and sacked.[90]

Overseas deployments and peacekeeping operations

In addition to its Support Base in Djibouti, the PLA operates a base in Tajikistan and a listening station in Cuba.[91][92] The Espacio Lejano Station in Argentina is operated by a unit of a PLA.[93][94] The PLAN has also undertaken rotational deployments of its warships at the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia.[95][96]

The People's Republic of China has sent the PLA to various hotspots as part of China's role as a prominent member of the United Nations.[97] Such units usually include engineers and logistical units and members of the paramilitary People's Armed Police and have been deployed as part of peacekeeping operations in Lebanon,[98][99] the Republic of the Congo,[98] Sudan,[100] Ivory Coast,[101] Haiti,[102][103] and more recently, Mali and South Sudan.[98][104]

Engagements

- 1927–1950: Chinese Civil War[105]

- 1937–1945: Second Sino-Japanese War[106]

- 1949: Yangtze incident against British warships on the Yangtze River[107]

- 1949: Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China[108]

- 1950: Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China[109]

- 1950–1953: Korean War under the banner of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army[110]

- 1954–1955: First Taiwan Strait Crisis[111]

- 1955–1970: Vietnam War[112]

- 1958: Second Taiwan Strait Crisis at Quemoy and Matsu[113]

- 1962: Sino-Indian War[114]

- 1967: Border skirmishes with India[33]

- 1969: Sino-Soviet border conflict[115]

- 1974: Battle of the Paracel Islands with South Vietnam[116]

- 1979: Sino-Vietnamese War[117]

- 1979–1990: Sino-Vietnamese conflicts[118]

- 1988: Johnson South Reef Skirmish with Vietnam[119]

- 1989: Enforcement of martial law in Beijing during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre[120]

- 1990: Barin uprising[121]

- 1995–1996: Third Taiwan Strait Crisis[122]

- 2007–present: UNIFIL peacekeeping operations in Lebanon[98]

- 2009–present: Anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden[123]

- 2014: Search and rescue efforts for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370[124]

- 2014: UN peacekeeping operations in Mali[125]

- 2015: UNMISS peacekeeping operations in South Sudan[126]

- 2020–2021: China–India skirmishes[127]

As of at least early 2024, China has not fought a war since 1979 and has only fought relatively minor conflicts since.[17]: 72

Organization

The PLA is a component of the armed forces of China, which also includes the PAP, the reserves, and the militia.[128] The armed forces are controlled by the CCP under the doctrine of "the Party must always control the gun".(Chinese: 党指挥枪; pinyin: Dǎng zhǐhuī qiāng)[15] The PLA and the PAP have the largest delegation in the National People's Congress (NPC), which are elected by servicemember election committees of top-level military subdivisions, including the PLA's theater commands and service branches.[129] At the 14th National People's Congress; the joint delegation has 281 deputies—over 9% of the total—all of whom are CCP members.[130]

Central Military Commission

The PLA is governed by the Central Military Commission (CMC); under the arrangement of "one institution with two names", there exists a state CMC and a Party CMC, although both commissions have identical personnel, organization and function, and effectively work as a single body.[131] The only difference in membership between the two occurs for a few months every five years, during the period between a Party National Congress, when Party CMC membership changes, and the next ensuing National People's Congress, when the state CMC changes.[132]

The CMC is composed of a chairman, vice chairpersons and regular members. The chairman of the CMC is the commander-in-chief of the PLA, with the post generally held by the paramount leader of China; since 1989, the post has generally been held together with the CCP general secretary.[15][131][133] Unlike in other countries, the Ministry of National Defense and its Minister do not have command authority, largely acting as diplomatic liaisons of the CMC, insulating the PLA from external influence.[134] However, the Minister has always been a member of the CMC.[131]

- Chairman

- Xi Jinping (also General Secretary, President and Commander-in-chief of Joint Battle Command)

- Vice Chairmen

- General Zhang Youxia

- General He Weidong

- Members

- Chief of the Joint Staff Department (JSD) – General Liu Zhenli

- Director of the Political Work Department – Admiral Miao Hua

- Secretary of the Commission for Discipline Inspection – General Zhang Shengmin

Previously, the PLA was governed by four general departments; the General Political, the General Logistics, the General Armament, and the General Staff Departments. These were abolished in 2016 under the military reforms undertaken by Xi Jinping, replaced with 15 new functional departments directly reporting to the CMC:[135]

- General Office

- Joint Staff Department

- Political Work Department

- Logistic Support Department

- Equipment Development Department

- Training and Administration Department

- National Defense Mobilization Department

- Discipline Inspection Commission

- Politics and Legal Affairs Commission

- Science and Technology Commission

- Office for Strategic Planning

- Office for Reform and Organizational Structure

- Office for International Military Cooperation

- Audit Office

- Agency for Offices Administration

Included among the 15 departments are three commissions. The CMC Discipline Inspection Commission is charged with rooting out corruption.

Political leadership

The CCP maintains absolute control over the PLA.[136] It requires the PLA to undergo political education, instilling CCP ideology in its members.[137] Additionally, China maintains a political commissar system.[138] Regiment-level and higher units maintain CCP committees and political commissars (Chinese: 政治委员 or 政委).[138][139] Additionally, battalion-level and company-level units respectively maintain political directors and political instructors.[140] The political workers are officially equal to commanders in status.[137] The political workers are officially responsible for the implementation of party committee decisions, instilling and maintaining party discipline, providing political education, and working with other components of the political work system.[140]

As a rule, the political worker serves as the party committee secretary while the commander serves as the deputy secretary.[140] Key decisions in the PLA are generally made in the CCP committees throughout the military.[137] Due to the CCP's absolute leadership, non-CCP political parties, groups and organizations except the Communist Youth League of China are not allowed to establish organizations or have members in the PLA. Additionally, only the CCP is allowed to appoint the leading cadres at all levels of the PLA.[139]

Grades

Grades determine the command hierarchy from the CMC to the platoon level. Entities command lower-graded entities, and coordinate with like-graded entities.[141] Since 1988, all organizations, billets, and officers in the PLA have a grade.[142]

Civil–military relations within the wider state bureaucracy is also influenced by grades. The grading systems used by the armed forces and the government are parallel, making it easier for military entities to identify the civilian entities they should coordinate with.[141]

An officer's authority, eligibility for billets, pay, and retirement age is determined by grade.[143][141] Career progression includes lateral transfers between billets of the same grade, but which are not considered promotions.[144][145] An officer retiring to the civil service has their grade translated to the civil grade system;[141] their grade continues to progress and draw retirement benefits through the civil system rather than the armed forces.[146]

Historically, an officer's grade — or position (Chinese: 职务等级; pinyin: zhiwu dengji[147]) — was more important than their rank (Chinese: 军衔; pinyin: junxian[147]).[141] Historically, time-in-grade and time-in-rank requirements[148] and promotions were not synchronized;[144] multiple ranks were present in each grade[149] with all having the same authority.[146] Rank was mainly a visual aid to roughly determine relative position when interacting with Chinese and foreign personnel.[141] PLA etiquette preferred addressing personnel by position rather than by rank.[150] Reforms to a more rank-centric system began in 2021.[147] In 2023, a revised grade structure associated one rank per grade, with some ranks spanning multiple grades.[151]

Operational control

Operational control of combat units is divided between the service headquarters and domestic geographically based theatre commands.

Theatre commands are multi-service ("joint") organizations that are broadly responsible for strategy, plans, tactics, and policy specific to their assigned area of responsibility. In wartime, they will likely have full control of subordinate units; in peacetime, units also report to their service headquarters.[153] Force-building is the responsibility of the services and the CMC.[154] The five theatre commands, in order of stated significance are:[155]

- Eastern Theater Command

- Southern Theater Command

- Western Theater Command

- Northern Theater Command

- Central Theater Command

The service headquarters retain operational control in some areas within China and outside of China. For example, army headquarters controls or is responsible for the Beijing Garrison, the Tibet Military District, the Xinjiang Military District,[156] and border and coastal defences. The counterpiracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden are controlled by navy headquarters.[157] The JSD nominally controls operations beyond China's periphery,[158] but in practice this seems to apply only to army operations.[159]

Services and theater commands have the same grade. The overlap of areas or units of responsibility may create disputes requiring CMC arbitration.[159]

As part of the 2015 reforms, military regions were replaced by theatre commands in 2016.[160] Military regions were − uinlike the theatre commands − army-centric[161] peacetime administrative organizations,[162] and joint wartime commands were created on-demand by the army-dominated General Staff Department.[162]

Organization table

State-owned enterprises

Multiple state-owned enterprises have established internal People's Armed Forces Departments run by the People's Liberation Army.[164][165][166] The internal units are expected "to work together with grassroots organizations to collect intelligence and information, dissolve and/or eliminate security concerns at the budding stage," according to the People's Liberation Army Daily.[165]

Academic Institutions

There are two academic institutions directly subordinate to the CMC, the National Defense University and the National University of Defense Technology, and they are considered the two top military education institutions in China. There are also 35 institutions affiliated to the PLA's branches and arms, and 7 institutions affiliated to the People's Armed Police.[167]

Service branches

The PLA consists of four services (Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force) and four arms (Aerospace Force, Cyberspace Force, Information Support Force, and Joint Logistics Support Force).[168]

Services

The PLA maintains four services (Chinese: 军种; pinyin: jūnzhǒng): the Ground Force, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Rocket Force. Following the 200,000 and 300,000 personnel reduction announced in 2003 and 2005 respectively, the total strength of the PLA has been reduced from 2.5 million to around 2 million.[169] The reductions came mainly from non-combat ground forces, which would allow more funds to be diverted to naval, air, and strategic missile forces. This shows China's shift from ground force prioritization to emphasizing air and naval power with high-tech equipment for offensive roles over disputed territories, particularly in the South China Sea.[170]

Ground Force

The PLA Ground Force (PLAGF) is the largest of the PLA's five services with 975,000 active duty personnel, approximately half of the PLA's total manpower of around 2 million personnel.[12]: 260 The PLAGF is organized into twelve active duty group armies sequentially numbered from the 71st Group Army to the 83rd Group Army which are distributed to each of the PRC's five theatre commands, receiving two to three group armies per command. In wartime, numerous PLAGF reserve and paramilitary units may be mobilized to augment these active group armies. The PLAGF reserve component comprises approximately 510,000 personnel divided into thirty infantry and twelve anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) divisions. The PLAGF is led by Commander Liu Zhenli and Political Commissar Qin Shutong.[171]

Navy

Until the early 1990s, the PLA Navy (PLAN) performed a subordinate role to the PLA Ground Force (PLAGF). Since then it has undergone rapid modernisation. The 300,000 strong PLAN is organized into three major fleets: the North Sea Fleet headquartered at Qingdao, the East Sea Fleet headquartered at Ningbo, and the South Sea Fleet headquartered in Zhanjiang.[172] Each fleet consists of a number of surface ship, submarine, naval air force, coastal defence, and marine units.[173][12]: 261

The navy includes a 25,000 strong Marine Corps (organised into seven brigades), a 26,000 strong Naval Aviation Force operating several hundred attack helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.[12]: 263–264 As part of its overall programme of naval modernisation, the PLAN is in the stage of developing a blue water navy.[174] In November 2012, then Party General Secretary Hu Jintao reported to the CCP's 18th National Congress his desire to "enhance our capacity for exploiting marine resource and build China into a strong maritime power".[175] According to the United States Department of Defense, the PLAN has numerically the largest navy in the world.[176] The PLAN is led by Commander Dong Jun and Political Commissar Yuan Huazhi.[177]

Air Force

The 395,000 strong People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) was organized into five Theatre Command Air Forces (TCAF) and 24 air divisions.[178]: 249–259 As of 2024[update], the system has been changed into 11 Corps Deputy-grade "Bases" controlling air brigades.[179] Divisions have been mostly converted to brigades,[179] although some (specifically the Bomber divisions, and some of the special mission units)[180] remain operational as divisions. The largest operational units within the Aviation Corps is the air division, which has 2 to 3 aviation regiments, each with 20 to 36 aircraft. An Air Brigade has from 24 to 50 aircraft.[181]

The surface-to-air missile (SAM) Corps is organized into SAM divisions and brigades. There are also three airborne divisions manned by the PLAAF. J-XX and XXJ are names applied by Western intelligence agencies to describe programs by the People's Republic of China to develop one or more fifth-generation fighter aircraft.[182][183] The PLAAF is led by Commander Chang Dingqiu and Political Commissar Guo Puxiao.[184][185]

Rocket Force

The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) is the main strategic missile force of the PLA and consists of at least 120,000 personnel.[12]: 259 It controls China's nuclear and conventional strategic missiles.[186] China's total nuclear arsenal size is estimated to be between 100 and 400 thermonuclear warheads. The PLARF is organized into bases sequentially numbered from 61 through 67, wherein the first six are operational and allocated to the nation's theatre commands while Base 67 serves as the PRC's central nuclear weapons storage facility.[187] The PLARF is led by Command Li Yuchao and Political Commissar Xu Zhongbo.[188]

Arms

The PLA maintains four arms (Chinese: 兵种): the Aerospace Force, the Cyberspace Force, the Information Support Force, and the Joint Logistics Support Force. The four-arm system was established on 19 April 2024.[168]

Personnel

Recruitment and terms of service

The PLA began as an all-volunteer force. In 1955, as part of an effort to modernize the PLA, the first Military Service Law created a system of compulsory military service.[4] Since the late 1970s, the PLA has been a hybrid force that combines conscripts and volunteers.[4][189][190] Conscripts who fulfilled their service obligation can stay in the military as volunteer soldiers for a total of 16 years.[4][190] De jure, military service with the PLA is obligatory for all Chinese citizens. However, mandatory military service has not been enacted in China since 1949.[191][192]

Women and ethnic minorities

Women participated extensively in unconventional warfare, including in combat positions, in the Chinese Red Army during the revolutionary period, Chinese Civil War (1927–1949) and the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).[193][194] After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, along with the People's Liberation Army (PLA)'s transition toward the conventional military organization, the role of women in the armed forces gradually reduced to support, medical, and logistics roles.[193] It was considered a prestigious choice for women to join the military. Serving in the military opens up opportunities for education, training, higher status, and relocation to cities after completing the service. During the Cultural Revolution, military service was regarded as a privilege and a method to avoid political campaign and coresion.[193]

In the 1980s, the PLA underwent large-scale demobilization amid the Chinese economic reform, and women were discharged back to civilian society for economic development while the exclusion of women in the military expanded.[193] In the 1990s, the PLA revived the recruitment of female personnel in regular military formations but primarily focused on non-combat roles at specialized positions.[193] Most women were trained in areas such as academic/engineering, medics, communications, intelligence, cultural work, and administrative work, as these positions conform to the traditional gender roles. Women in the PLA were more likely to be cadets and officers instead of enlisted soldiers because of their specializations.[193] The military organization still preserved some female combat units as public exemplars of social equality.[193][194]

Both enlisted and cadet women personnel underwent the same basic training as their male counterparts in the PLA, but many of them serve in predominantly female organizations. Due to ideological reasons, the regulation governing the segregation of sex in the PLA is prohibited, but a quasi-segregated arrangement for women's organizations is still applied through considerations of convenience.[193] Women were likelier to hold commanding positions in female-heavy organizations such as medical, logistic, research, and political work units, but sometimes in combat units during peacetime.[193] In PLAAF, women traditionally pilot transport aircraft or serve as crew members.[195] There had been a small number of high-ranking female officials in the PLA since 1949, but the advancement of position had remained relatively uncommon.[193][194] In the 2010s, women were increasingly serving in combat roles, in mixed-gender organizations alongside their male counterparts, and to the same physical standard.[194]

The military actively promotes opportunities for women in the military, such as celebrating International Women's Day for the members of the armed forces, publicizing the number of firsts for female officers and enlisted personnel, including deployments with peacekeeping forces or serving on PLA Navy's first aircraft carrier, announcing female military achievements in state media, and promoting female special forces through news reports or popular media.[194] PLA does not publish detailed gender composition of its armed forces, but the Jamestown Foundation estimated approximately 5% of the active military force in China is female.[196]

National unity and territorial integrity are central themes of the Chinese Communist Revolution. The Chinese Red Army and the succeeding PLA actively recruited ethnic minorities. During the Chinese Civil War, Mongol cavalry units were formed. During the Korean War, as many as 50,000 ethnic Koreans in China volunteered to join the PLA. PLA's recruitment of minorities generally correlates to state policies. During the early years, minorities were given preferential treatment, with special attention given to recruitment and training. In the 1950s, ethnic Mongols accounted for 52% of all officers in Inner Mongolia military region. During the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, armed forces emphasized "socialist culture", assimilation policies, and the construction of common identities between soldiers of different ethnicities.[197]

For ethnic minority cadets and officials, overall development follows national policies. Typically, minority officers hold officer positions in their home regions. Examples included over 34% of the battalion and regimental cadres in Yi autonomous region militia were of the Yi ethnicity, and 45% of the militia cadres in Tibetan local militia were of Tibetan ethnicity. Ethnical minorities achieved high-ranking positions in the PLA, and the percentage of appointments appears to follow the ratio of the Chinese population composition.[197] Prominent figures included ethnic Mongol general Ulanhu, who served in high-ranking roles in the Inner Mongolian region and as vice president of China, and ethnic Uyghur Saifuddin Azizi, a Lieutenant General who served in the CCP Central Committee.[197] There were a few instances of ethnic distrust within the PLA, with one prominent example being the defection of Margub Iskhakov, an ethnic Muslim Tatar PLA general, to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. However, his defection largely contributed to his disillusion with the failed Great Leap Forward policies, instead of his ethnic background.[198] In modern times, ethnic representation is most visible among junior-ranking officers. Only a few minorities reach the highest-ranking positions.[198]

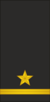

Rank structure

Officers

Other ranks

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 一级军士长 Yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

二级军士长 Èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

三级军士长 Sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

四级军士长 Sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

列兵 Lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 海军一级军士长 Hǎijūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军二级军士长 Hǎijūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军三级军士长 Hǎijūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军四级军士长 Hǎijūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军上士 Hǎijūn shàngshì |

海军中士 Hǎijūn zhōngshì |

海军下士 Hǎijūn xiàshì |

海军上等兵 Hǎijūn shàngděngbīng |

海军列兵 Hǎijūn lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 空军一级军士长 Kōngjūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军二级军士长 Kōngjūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军三级军士长 Kōngjūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军四级军士长 Kōngjūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军上士 Kōngjūn shàngshì |

空军中士 Kōngjūn zhōngshì |

空军下士 Kōngjūn xiàshì |

空军上等兵 Kōngjūn shàngděngbīng |

空军列兵 Kōngjūn lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No equivalent |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Master sergeant class one 一级军士长 yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class two 二级军士长 èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class three 三级军士长 sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class four 四级军士长 sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Sergeant first class 上士 shàngshì |

Sergeant 中士 zhōngshì |

Corporal 下士 xiàshì |

Private first class 上等兵 shàngděngbīng |

Private 列兵 lièbīng

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 一级军士长 Yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

二级军士长 Èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

三级军士长 Sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

四级军士长 Sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

列兵 Lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weapons and equipment

According to the United States Department of Defense, China is developing kinetic-energy weapons, high-powered lasers, high-powered microwave weapons, particle-beam weapons, and electromagnetic pulse weapons with its increase of military fundings.[200]

The PLA has said of reports that its modernisation is dependent on sales of advanced technology from American allies, senior leadership have stated "Some have politicized China's normal commercial cooperation with foreign countries, damaging our reputation." These contributions include advanced European diesel engines for Chinese warships, military helicopter designs from Eurocopter, French anti-submarine sonars and helicopters,[201] Australian technology for the Houbei class missile boat,[202] and Israeli supplied American missile, laser and aircraft technology.[203]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's data, China became the world's third largest exporter of major arms in 2010–14, an increase of 143 percent from the period 2005–2009.[204] SIPRI also calculated that China surpassed Russia to become the world's second largest arms exporter by 2020.[205]

China's share of global arms exports hence increased from 3 to 5 percent. China supplied major arms to 35 states in 2010–14. A significant percentage (just over 68 percent) of Chinese exports went to three countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. China also exported major arms to 18 African states. Examples of China's increasing global presence as an arms supplier in 2010–14 included deals with Venezuela for armoured vehicles and transport and trainer aircraft, with Algeria for three frigates, with Indonesia for the supply of hundreds of anti-ship missiles and with Nigeria for the supply of several unmanned combat aerial vehicles.[206]

Following rapid advances in its arms industry, China has become less dependent on arms imports, which decreased by 42 percent between 2005–09 and 2010–14. Russia accounted for 61 percent of Chinese arms imports, followed by France with 16 percent and Ukraine with 13 per cent. Helicopters formed a major part of Russian and French deliveries, with the French designs produced under licence in China.[206]

Over the years, China has struggled to design and produce effective engines for combat and transport vehicles. It continued to import large numbers of engines from Russia and Ukraine in 2010–14 for indigenously designed combat, advanced trainer and transport aircraft, and naval ships. It also produced British-, French- and German-designed engines for combat aircraft, naval ships and armoured vehicles, mostly as part of agreements that have been in place for decades.[206]

In August 2021, China tested a nuclear-capable hypersonic missile that circled the globe before speeding towards its target.[207] The Financial Times reported that "the test showed that China had made astounding progress on hypersonic weapons and was far more advanced than U.S. officials realized."[208] During the Exercise Zapad-81 in 2021 with Russian forces, most of the gear were novel Chinese arms such as the KJ-500 airborne early warning and control aircraft, J-20 and J-16 fighters, Y-20 transport planes, and surveillance and combat drones.[209] Another joint forces exercise took place in August 2023 near Alaska.[210]

On 24 September 2024, the PLARF performed its first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) test over the Pacific Ocean since the early 1980s.[211][212]

Cyberwarfare

There is a belief in the Western military doctrines that the PLA have already begun engaging countries using cyber-warfare.[213] There has been a significant increase in the number of presumed Chinese military initiated cyber events from 1999 to the present day.[214]

Cyberwarfare has gained recognition as a valuable technique because it is an asymmetric technique that is a part of information operations and information warfare. As is written by two PLAGF Colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui in the book Unrestricted Warfare, "Methods that are not characterized by the use of the force of arms, nor by the use of military power, nor even by the presence of casualties and bloodshed, are just as likely to facilitate the successful realization of the war's goals, if not more so.[215]

While China has long been suspected of cyber spying, on 24 May 2011 the PLA announced the existence of having 'cyber capabilities'.[216]

In February 2013, the media named "Comment Crew" as a hacker military faction for China's People's Liberation Army.[217] In May 2014, a Federal Grand Jury in the United States indicted five Unit 61398 officers on criminal charges related to cyber attacks on private companies based in the United States after alleged investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation who exposed their identities in collaboration with US intelligence agencies such as the CIA.[218][219]

In February 2020, the United States government indicted members of China's People's Liberation Army for the 2017 Equifax data breach, which involved hacking into Equifax and plundering sensitive data as part of a massive heist that also included stealing trade secrets, though the CCP denied these claims.[220][221]

Nuclear capabilities

The first of China's nuclear weapons tests took place in 1964, and its first hydrogen bomb test occurred in 1967 at Lop Nur. Tests continued until 1996, when the country signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), but did not ratify it.[222]

The number of nuclear warheads in China's arsenal remains a state secret.[223] There are varying estimates of the size of China's arsenal. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and Federation of American Scientists estimated in 2024 that China has a stockpile of approximately 438 nuclear warheads,[223][224] while the United States Department of Defense put the estimate at more than 500 operational nuclear warheads,[225] making it the third-largest in the world.

China's policy has traditionally been one of no first use while maintaining a deterrent retaliatory force targeted for countervalue targets.[226] According to a 2023 study by the National Defense University, China's nuclear doctrine has historically leaned toward maintaining a secure second-strike capability.[227]

Space

Having witnessed the crucial role of space to United States military success in the Gulf War, China continues to view space as a critical domain in both conflict and international strategic competition.[228][229] The PLA operates a various satellite constellations performing reconnaissance, navigation, communication, and counterspace functions.[230][231][232][233] Planners at PLA's National Defense University project China's space actions as retaliatory or preventative, following conditions like an attack on a Chinese satellite, an attack on China, or the interruption of a PLA amphibious landing.[234] According to this approach, PLA planners assume that the country must have the capacity for retaliation and second-strike capability against a powerful opponent.[234] PLA planners envision a limited space war and therefore seek to identify weak but critical nodes in other space systems.[234]

Significant components of the PLA's space-based reconnaissance include Jianbing (vanguard) satellites with cover names Yaogan (遥感; 'remote sensing') and Gaofen (高分; 'high resolution').[230][235] These satellites collect electro-optical (EO) imagery to collect a literal representation of a target, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery to penetrate the cloudy climates of southern China,[236] and electronic intelligence (ELINT) to provide targeting intelligence on adversarial ships.[237][238] The PLA also leverages a restricted, high-performance service of the country's BeiDou positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) satellites for its forces and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms.[239][240] For secure communications, the PLA uses the Zhongxing and Fenghuo series of satellites which enable secure data and voice transmission over C-band, Ku-band, and UHF.[232] PLA deployment of anti-satellite and counterspace satellites including those of the Shijian and Shiyan series have also brought significant concern from western nations.[241][233][242]

The PLA also plays a significant role in the Chinese space program.[228] To date, all the participants have been selected from members of the PLA Air Force.[228] China became the third country in the world to have sent a man into space by its own means with the flight of Yang Liwei aboard the Shenzhou 5 spacecraft on 15 October 2003,[243] the flight of Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng aboard Shenzhou 6 on 12 October 2005,[244] and Zhai Zhigang, Liu Boming, and Jing Haipeng aboard Shenzhou 7 on 25 September 2008.[245]

The PLA started the development of an anti-ballistic and anti-satellite system in the 1960s, code named Project 640, including ground-based lasers and anti-satellite missiles.[246] On 11 January 2007, China conducted a successful test of an anti-satellite missile, with an SC-19 class KKV.[247]

The PLA has tested two types of hypersonic space vehicles, the Shenglong Spaceplane and a new one built by Chengdu Aircraft Corporation. Only a few pictures have appeared since it was revealed in late 2007. Earlier, images of the High-enthalpy Shock Waves Laboratory wind tunnel of the CAS Key Laboratory of high-temperature gas dynamics (LHD) were published in the Chinese media. Tests with speeds up to Mach 20 were reached around 2001.[248][249]

Budget

| Publication date |

Value (billions of US$) |

|---|---|

| March 2000 | 14.6[citation needed] |

| March 2001 | 17.0[citation needed] |

| March 2002 | 20.0[citation needed] |

| March 2003 | 22.0[citation needed] |

| March 2004 | 24.6[citation needed] |

| March 2005 | 29.9[citation needed] |

| March 2006 | 35.0[citation needed] |

| March 2007 | 44.9[citation needed] |

| March 2008 | 58.8[250] |

| March 2009 | 70.0[citation needed] |

| March 2010 | 76.5[251] |

| March 2011 | 90.2[251] |

| March 2012 | 103.1[251] |

| March 2013 | 116.2[251] |

| March 2014 | 131.2[251] |

| March 2015 | 142.4[251] |

| March 2016 | 143.7[251] |

| March 2017 | 151.4[251] |

| March 2018 | 165.5[252] |

| March 2019 | 177.6[253] |

| May 2020 | 183.5[254] |

| March 2021 | 209.4[255] |

| March 2022 | 229.4[256] |

| March 2023 | 235.8[citation needed] |

China's official military budget for 2024 was at 1.67 trillion yuan (US$231 billion), which is an increase of 7.2% over the last year.[257] The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimated that China's military expenditure was US$296 billion in 2023, the second-largest in the world after the United States and accounting for 12 percent of the world's defence expenditures.[258]

Symbols

Anthem

The March of the Chinese People's Liberation Army was adopted as the military anthem by the Central Military Commission on 25 July 1988.[259] The lyrics of the anthem were written by composer Gong Mu (real name: Zhang Yongnian; Chinese: 张永年) and the music was composed by Korea-born Chinese composer Zheng Lücheng.[260][261]

Flag and insignia

The PLA's insignia consists of a roundel with a red star bearing the two Chinese characters "八一"(literally "eight-one"), referring to the Nanchang uprising which began on 1 August 1927 (first day of the eighth month) and symbolic as the CCP's founding of the PLA.[262] The inclusion of the two characters ("八一") is symbolic of the party's revolutionary history carrying strong emotional connotations of the political power which it shed blood to obtain. The flag of the Chinese People's Liberation Army is the war flag of the People's Liberation Army; the layout of the flag has a golden star at the top left corner and "八一" to the right of the star, placed on a red field. Each service branch also has its flags: The top 5⁄8 of the flags is the same as the PLA flag; the bottom 3⁄8 are occupied by the colors of the branches.[263]

The flag of the Ground Forces has a forest green bar at the bottom. The naval ensign has stripes of blue and white at the bottom. The Air Force uses a sky blue bar. The Rocket Force uses a yellow bar at the bottom. The forest green represents the earth, the blue and white stripes represent the seas, the sky blue represents the air and the yellow represents the flare of missile launching.[264][265]

-

PLA

See also

- Outline of the Chinese Civil War

- Outline of the military history of the People's Republic of China

- Republic of China Armed Forces

References

- ^ "【延安记忆】"中国人民解放军"称谓由此开始". 1 August 2020. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "1947年10月10日,《中国人民解放军宣言》发布". 中国军网. 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "中国共产党领导的红军改编为八路军的背景和改编情况 – 太行英雄网". Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Allen, Kenneth (14 January 2022). "The Evolution of the PLA's Enlisted Force: Conscription and Recruitment (Part One)". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

Following the setback of the Cultural Revolution, in the late 1970s, the PLA embarked on an ambitious program to modernize many aspects of the military, including education, training, and recruitment. Conscripts and volunteers were combined into a single system that allowed conscripts who fulfilled their service obligation to stay in the military as volunteer soldiers for a total of 16 years.

- ^ a b The International Institute for Strategic Studies 2022, p. 255.

- ^ a b "Trends in Military Expenditure 2023" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. April 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Xue, Maryann (4 July 2021). "China's arms trade: which countries does it buy from and sell to?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b "TIV of arms imports/exports from China, 2010–2021". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 7 February 2022. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Benton, Gregor (1999). New Fourth Army: Communist Resistance Along the Yangtze and the Huai, 1938–1941. University of California Press. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-520-21992-2. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Fravel, M. Taylor (2019). Active Defense: China's Military Strategy since 1949. Vol. 2. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv941tzj. ISBN 978-0-691-18559-0. JSTOR j.ctv941tzj. S2CID 159282413.

- ^ "Global military spending remains high at $1.7 trillion". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 2 May 2018. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e International Institute for Strategic Studies (2020). The Military Balance. London: Routledge. doi:10.1080/04597222.2020.1707967. ISBN 978-0367466398.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019, p. 148.

- ^ a b Saunders et al. 2019, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d e Saunders et al. 2019, p. 521.

- ^ "The PLA Navy's New Historic Missions: Expanding Capabilities for a Re-emergent Maritime Power" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b Garlick, Jeremy (2024). Advantage China: Agent of Change in an Era of Global Disruption. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-25231-8.

- ^ Carter, James (4 August 2021). "The Nanchang Uprising and the birth of the PLA". The China Project. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "History of the PLA's Ground Force Organisational Structure and Military Regions". Royal United Services Institute. 17 June 2004. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Bianco, Lucien (1971). Origins of the Chinese Revolution, 1915–1949. Stanford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8047-0827-2.

- ^ Zedong, Mao (2017). On Guerilla Warfare: Mao Tse-Tung On Guerilla Warfare. Martino Fine Books. ISBN 978-1-68422-164-6.

- ^ "The Chinese Revolution of 1949". United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Ken Allen, Chapter 9, "PLA Air Force Organization" Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, The PLA as Organization, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Andrew N.D. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2002), 349.

- ^ "中国人民解放军海军成立70周年多国海军活动新闻发布会在青岛举行". mod.gov.cn (in Chinese). Ministry of National Defence of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- ^ a b "China's People's Liberation Army, the world's second largest conventional..." UPI. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Loh, Dylan M.H. (2024). China's Rising Foreign Ministry: Practices and Representations of Assertive Diplomacy. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503638204.

- ^ Pamphlet number 30-51, Handbook on the Chinese Communist Army (PDF), Department of the Army, 7 December 1960, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011, retrieved 1 April 2011

- ^ a b Stewart, Richard (2015). The Korean War: The Chinese Intervention. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5192-3611-1. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Cliff, Roger; Fei, John; Hagen, Jeff; Hague, Elizabeth; Heginbotham, Eric; Stillion, John (2011), "The Evolution of Chinese Air Force Doctrine", Shaking the Heavens and Splitting the Earth, Chinese Air Force Employment Concepts in the 21st Century, RAND Corporation, pp. 33–46, ISBN 978-0-8330-4932-2, JSTOR 10.7249/mg915af.10

- ^ Hoffman, Steven A. (1990). India and the China Crisis. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 101–104. ISBN 978-0-520-30172-6. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Van Tronder, Gerry (2018). Sino-Indian War: Border Clash: October–November 1962. Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-5267-2838-8. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b Brahma Chellaney (2006). Asian Juggernaut: The Rise of China, India, and Japan. HarperCollins. p. 195. ISBN 978-8172236502.

Indeed, Beijing's acknowledgement of Indian control over Sikkim seems limited to the purpose of facilitating trade through the vertiginous Nathu-la Pass, the scene of bloody artillery duels in September 1967 when Indian troops beat back attacking Chinese forces.

- ^ Van Praagh, David (2003). Greater Game: India's Race with Destiny and China. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 301. ISBN 978-0773525887. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

(Indian) jawans trained and equipped for high-altitude combat used US provided artillery, deployed on higher ground than that of their adversaries, to decisive tactical advantage at Nathu La and Cho La near the Sikkim-Tibet border.

- ^ Hoontrakul, Ponesak (2014), "Asia's Evolving Economic Dynamism and Political Pressures", in P. Hoontrakul; C. Balding; R. Marwah (eds.), The Global Rise of Asian Transformation: Trends and Developments in Economic Growth Dynamics, Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 37, ISBN 978-1-137-41236-2, archived from the original on 25 December 2018, retrieved 6 August 2021,

Cho La incident (1967) – Victorious: India / Defeated : China

- ^ a b Li, Xiaobing (2007). A History of the Modern Chinese Army. University Press of Kentucky. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2jcq4k. ISBN 978-0-8131-2438-4. JSTOR j.ctt2jcq4k.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. "Four Modernizations Era". A Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ 人民日报 (31 January 1963). 在上海举行的科学技术工作会议上周恩来阐述科学技术现代化的重大意义 [Science and Technology in Shanghai at the conference on Zhou Enlai explained the significance of modern science and technology]. People's Daily (in Chinese). Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. p. 1. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Mason, David (1984). "China's Four Modernizations: Blueprint for Development or Prelude to Turmoil?". Asian Affairs. 11 (3): 47–70. doi:10.1080/00927678.1984.10553699. ISSN 0092-7678. JSTOR 30171968.

- ^ Vincent, Travils (9 February 2022). "Why Won't Vietnam Teach the History of the Sino-Vietnamese War?". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Fravel, M. Taylor (2007). "Power Shifts and Escalation: Explaining China's Use of Force in Territorial Disputes". International Security. 32 (3): 44–83. doi:10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.44. ISSN 0162-2889. JSTOR 30130518. S2CID 57559936.

- ^ China and Afghanistan, Gerald Segal, Asian Survey, Vol. 21, No. 11 (Nov., 1981), University of California Press

- ^ a b c Hilali, A.Z (September 2001). "China's response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan". Central Asian Survey. 20 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1080/02634930120095349. ISSN 0263-4937. S2CID 143657643.

- ^ a b Starri, S. Frederick (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 157–158. ISBN 0765613182.

- ^ Szczudlik-Tatar, Justyna (October 2014). "China's Evolving Stance on Afghanistan: Towards More Robust Diplomacy with "Chinese Characteristics"" (PDF). Strategic File. 58 (22). Polish Institute of International Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Galster, Steve (9 October 2001). "Volume II: Afghanistan: Lessons from the Last War". National Security Archive, George Washington University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Godwin, Paul H. B. (2019). The Chinese Defense Establishment: Continuity And Change In The 1980s. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-31540-0. Archived from the original on 11 February 2024. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Lin, Shuanglin (2022). China's Public Finance: Reforms, Challenges, and Options. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-09902-8.

- ^ a b c Saunders et al. 2019, p. 523.

- ^ Zissis, Carin (5 December 2006). "Modernizing the People's Liberation Army of China". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019, p. 51.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019, p. 520.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019, p. 526.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019, p. 531.

- ^ "PLA's "Absolute Loyalty" to the Party in Doubt". The Jamestown Foundation. 30 April 2009. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "Xi Jinping insists on PLA's absolute loyalty to Communist Party". The Economic Times. 20 August 2018. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Chan, Minnie (23 September 2022). "China's military told to 'resolutely do what the party asks it to do'". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b c The Political System of the People's Republic of China. Chief Editor Pu Xingzu, Shanghai, 2005, Shanghai People's Publishing House. ISBN 7-208-05566-1, Chapter 11 The State Military System.

- ^ News of the Communist Party of China, Hyperlink Archived 13 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ^ Farley, Robert (1 September 2021). "China Has Not Forgotten the Lessons of the Gulf War". National Interest. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Scobell, Andrew (2011). Chinese Lessons from Other Peoples' Wars (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. ISBN 978-1-58487-511-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Lampton, David M. (2024). Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-5381-8725-8.

- ^ Sasaki, Tomonori (23 September 2010). "China Eyes the Japanese Military: China's Threat Perception of Japan since the 1980s". The China Quarterly. 203: 560–580. doi:10.1017/S0305741010000597. ISSN 1468-2648. S2CID 153828298. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Sakaguchi, Yoshiaki; Mayama, Katsuhiko (1999). "Significance of the War in Kosovo for China and Russia" (PDF). NIDS Security Reports (3): 1–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Sun, Yun (8 April 2020). "China's Strategic Assessment of Afghanistan". War on the Rocks. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b Chase, Michael S. (19 September 2007). "China's Assessment of the War in Iraq: America's "Deepest Quagmire" and the Implications for Chinese National Security". China Brief. 7 (17). The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b Ji, You (1999). "The Revolution in Military Affairs and the Evolution of China's Strategic Thinking". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 21 (3): 344–364. doi:10.1355/CS21-3B (inactive 13 November 2024). ISSN 0129-797X. JSTOR 25798464. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Wortzel, Larry M. (2007). "The Chinese People's Liberation Army and Space Warfare". Space Policy. American Enterprise Institute. JSTOR resrep03013.

- ^ Hjortdal, Magnus (2011). "China's Use of Cyber Warfare: Espionage Meets Strategic Deterrence". Journal of Strategic Security. 4 (2): 1–24. doi:10.5038/1944-0472.4.2.1. ISSN 1944-0464. JSTOR 26463924. S2CID 145083379.

- ^ Jinghua, Lyu. "What Are China's Cyber Capabilities and Intentions?". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (2023). China's Relations with Africa: a New Era of Strategic Engagement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0.

- ^ Osborn, Kris (21 March 2022). "China Modernizes Its Russian-Built Destroyers With New Weapons". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Gao, Charlie (1 January 2021). "How China Got Their Own Russian-Made Su-27 "Flanker" Jets". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Kadam, Tanmay (26 September 2022). "2 Russian Su-30 Fighters, The Backbone Of Indian & Chinese Air Force, Knocked Out By Ukraine – Kiev Claims". The Eurasian Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Larson, Caleb (11 May 2021). "China's Deadly Kilo-Class Submarines Are From Russia With Love". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Vavasseur, Xavier (21 August 2022). "Five Type 052D Destroyers Under Construction In China". Naval News. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Wertheim, Eric (January 2020). "China's Luyang III/Type 052D Destroyer Is a Potent Adversary". United States Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Rogoway, Tyler; Helfrich, Emma (18 July 2022). "China's J-10 Fighter Spotted In New 'Big Spine' Configuration (Updated)". The Warzone. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Osborn, Kris (4 October 2022). "China Boosts J-20 Fighter Production to Counter U.S. Stealth Fighters". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Funaiole, Matthew P. (4 August 2021). "A Glimpse of Chinese Ballistic Missile Submarines". Center for Strategic & International Studies. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023.

- ^ Lendon, Brad (25 June 2022). "Never mind China's new aircraft carrier, these are the ships the US should worry about". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "Fujian aircraft carrier doesn't have radar, weapon systems yet, photos show". South China Morning Post. 19 July 2022. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Hendrix, Jerry (6 July 2022). "The Ominous Portent of China's New Carrier". National Review. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "China establishes Rocket Force and Strategic Support Force – China Military Online". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Duan, Lei (2024). "Towards a More Joint Strategy: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms and Militia Reconstruction". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.). China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment. Leiden University Press. ISBN 9789087284411. JSTOR jj.15136086.

- ^ "Exclusive: Massive parade tipped for PLA's 90th birthday". South China Morning Post. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (30 July 2017). "China Shows Off Military Might as Xi Jinping Tries to Cement Power". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Chinese military purge exposes weakness, could widen". Reuters. 31 December 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "Charting China's 'great purge' under Xi". BBC News. 22 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ Yan, Sophia (10 July 2024). "China constructing secret military base in Tajikistan to crush threat from Taliban". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 22 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Secret Signals: Decoding China's Intelligence Activities in Cuba". Center for Strategic and International Studies. 1 July 2024. Archived from the original on 2 July 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Garrison, Cassandra (31 January 2019). "China's military-run space station in Argentina is a 'black box'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Eyes on the Skies: China's Growing Space Footprint in South America". Center for Strategic and International Studies. 4 October 2022. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Cheang, Sopheng; David, Rising (8 May 2024). "Chinese warships have been docked in Cambodia for 5 months, but government says it's not permanent". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Chinese warships rotate at Cambodia's Ream naval base". Radio Free Asia. 4 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Gowan, Richard (14 September 2020). "China's pragmatic approach to UN peacekeeping". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Rowland, Daniel T. (September 2022). Chinese Security Cooperation Activities: Trends and Implications for US Policy (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ China's Role in UN Peacekeeping (PDF) (Report). Institute for Security & Development Policy. March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Daniel M. Hartnett, 2012-03-13, China's First Deployment of Combat Forces to a UN. Peacekeeping Mission—South Sudan Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission

- ^ Bernard Yudkin Geoxavier, 2012-09-18, China as Peacekeeper: An Updated Perspective on Humanitarian Intervention Archived 31 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Journal of International Affairs

- ^ "Chinese Peacekeepers to Haiti: Much Attention, More Confusion". Royal United Services Institute. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 11 February 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle (14 July 2022). "China pushes for U.N. arms embargo on Haiti criminal gangs". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Dyrenforth, Thomas (19 August 2021). "Beijing's Blue Helmets: What to Make of China's Role in UN Peacekeeping in Africa". Modern War Institute. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Lew, Christopher R.; Leung, Pak-Wah, eds. (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Civil War. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-0810878730. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Paine, S. C. M. (2012). The Wars for Asia, 1911–1949. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-139-56087-0. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Security Check Required". Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Sinkiang and Sino-Soviet Relations" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p. 32 (6 Oct); Goldstein (1997), p. 45 (7 Oct).

- ^ Ryan, Mark A.; Finkelstein, David M.; McDevitt, Michael A. (2003). Chinese warfighting: The PLA experience since 1949. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. p. 125. ISBN 0-7656-1087-6.

- ^ Rushkoff, Bennett C. (1981). "Eisenhower, Dulles and the Quemoy-Matsu Crisis, 1954–1955". Political Science Quarterly. 96 (3): 465–480. doi:10.2307/2150556. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2150556.

- ^ Zhai, Qiang (2000). China and the Vietnam wars, 1950–1975. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807825327. OCLC 41564973.

- ^ The 1958 Taiwan Straits Crisis_ A Documented History. 1975.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (2018). China's India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-909163-8. OCLC 1034558154.

- ^ "Некоторые малоизвестные эпизоды пограничного конфликта на о. Даманском". Военное оружие и армии Мира. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Carl O. Schustser. "Battle for Paracel Islands". Archived 20 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Elleman, Bruce A. (2001). Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989. Routledge. p. 297. ISBN 0415214742.

- ^ Carlyle A. Thayer, "Security Issues in Southeast Asia: The Third Indochina War", Conference on Security and Arms Control in the North Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, August 1987.

- ^ Koo, Min Gyo (2010). Island Disputes and Maritime Regime Building in East Asia. The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific. New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 154. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-89670-0. ISBN 978-0-387-89669-4.