Phoenix of Hiroshima

The Phoenix of Hiroshima (foreground) in Hong Kong Harbor, en route to North Vietnam, 1967.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Phoenix of Hiroshima |

| Builder | Mr. Yotsuda in Miyajimaguchi |

| Launched | May 5, 1954 |

| Maiden voyage | 1954 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | double-ended ketch |

| Tonnage | 30 tons |

| Length | 50 feet (15 m) |

The Phoenix of Hiroshima was a 50-foot, 30-ton yacht that circumnavigated the globe and was later involved in several famous protest voyages. Between its launch in 1954 and its sinking in 2010, the Phoenix carried a family around the world, was used to make protest voyages against nuclear weapons, was declared a Japanese national shrine, and ended up offered free on Craigslist, gutted and stripped of masts, phoenix figurehead and every identifying mark but the words "Phoenix of Hiroshima."

Construction and launch

Named for the mythological bird which rises from the ashes of its own destruction, the Phoenix was built near Hiroshima and launched May 5, 1954. It was designed by Dr. Earle L. Reynolds (1910–1998), an anthropologist who had been sent to Hiroshima by the National Academy of Sciences to research the effects of the first atomic bomb on the physical growth and development of surviving Japanese children (1951–1954).[1] In Oriental mythology the Phoenix is a bird which appears only in time of universal peace.

Dr. Reynolds patterned the 50-foot (15 m), double-ended ketch on the Colin Archer design used for sturdy Norwegian fishing vessels. The boat rose symbolically from the ashes of the city destroyed by the first atomic bomb but it also rose, over the period of a year and a half, from the small unprepossessing shipyard of Mr. Yotsuda in Miyajimaguchi, across the Inland Sea of Japan from the famous Miyajima Shrine. Until approached by Reynolds, Yotsuda had only built sampans and was struggling to recover financially from the second World War.

The boat was originally constructed entirely of native Japanese woods. (In 1956, the mainmast became infested with borer-type insects and was replaced in Auckland with one of native New Zealand kauri pine.) It was double-planked, mahogany over hinoki (cypress). The hull was hinoki above the water line, sugi (cryptomeria cedar) below. The cabins below decks consisted of mahogany, camphor, cherry, chestnut and Japanese cabinet woods.[2]

Voyage around the world, 1954–1958

When Dr. Reynolds finished the first three years of what was intended to be a longitudinal study[3] interrupted by a one-year sabbatical, he and his family (wife Barbara Leonard Reynolds, second son Ted, 16, daughter Jessica, 10, and three Hiroshima yachtsmen) sailed the Phoenix around the world. Ted navigated the 30-ton vessel, using calculations from sun shots made with a hand-held sextant. The trip extended past the one year allotted and for a number of reasons, Reynolds did not resume his job in Hiroshima.

The first leg of the circumnavigation, from Japan to Hawaii, took 48 days, most of which were rough and stormy.[4] It was followed by ideal sailing weather to and through the South Seas: Tahiti, Moorea, Raiatea, Tahaa and Bora Bora in the Society Islands; Rarotonga, American Samoa, Fiji. From there they sailed to New Zealand (Auckland and Wellington); Australia (Sydney, the Great Barrier Reef, Cairns); Indonesia (Bali, Java).

They weathered a typhoon off the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, touched in at Rodrigues and Mauritius and changed course to round the tip of South Africa (Durban, Cape Town) rather than go through the Mediterranean during the Suez crisis; Brazil (Fortaleza); the east coast of the United States from New York, then south to the West Indies. They went through the Panama Canal to the Galapagos Islands, where they traded six packages of instant powdered milk, one can of shortening and two bottles of hot pepper sauce for a Galapagos tortoise, 11x11 inches across the shell, naming him Jonathan Mushmouth. (They had a legal permit issued in Ecuador, to take "two of every kind" of animal from the islands.) Years later they gave Jonathan to the Hanshin Zoo in Osaka, Japan, the zoo's first Galapagos tortoise. The Reynolds family expected Jonathan to outlive them but he died in the 1980s.

Hijacking of the Valinda

In the Galapagos the Phoenix just missed being hijacked by escaped convicts. The Historical Chronology of the Galapagos, 1535–2000 records in February 1958 that "The Phoenix, with Earle Reynolds, his wife Barbara, their children, Jessica and Ted and a Japanese crewmember arrived at Wreck Bay." They went on to Academy Bay where they found the French yacht Cle Du Sol, and just missed a previously arranged meeting with the American yacht Valinda. Convicts living in the penal colony on Isabela Island were asked to prepare a celebration on February 12 but on the 9th they revolted with stolen weapons and took the guards prisoners. The convicts boarded two fishing boats, the Teresita and the Ecuador. At Punta Moreno they took possession of the Viking. They then went to Santiago Island where they captured the Valinda belonging to William Rhodes Hervey Jr.[5] They reached the continent on the 17th and abandoned ship at Esmeraldas but were eventually captured by the police.

The Phoenix and Valinda had scheduled a rendezvous in James Bay on San Salvador Island on February 16. The Phoenix was there and waited all day but the Valinda never showed up. Months later, Earle read in a back issue of Life Magazine[6] that the Valinda had arrived in James Bay the night before ("while we were all asleep aboard the Phoenix, five miles away around the point") but was then hijacked by the 21 escapees from the penal colony who forced the crew to sail to Ecuador.[7]

Unaware of their close call, the Reynoldses proceeded on to the Marquesas and back to Hawaii. Two of the three Japanese men flew back to Japan from Panama. First mate Niichi (Nick) Mikami remained with the Phoenix. After 645 days, 1222 ports and 54,000 nautical miles (100,000 km), the Phoenix once again sailed into Honolulu harbor.[8][9][10]

Voyage to protest nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific, 1958

Technically this completed a circumnavigation of the globe but the trip had started in Japan and the Reynolds family intended to culminate it there. A change in plans delayed their return for two years. Their route back to Japan was blocked by the Enewetak Proving Ground, a 390,000-square-mile (1,000,000 km2) area of the Pacific declared off-limits to Americans by the U.S. government, which was using the area to test nuclear weapons during Operation Hardtack I. A smaller yacht, the Golden Rule, was docked near the Phoenix at the time. Its crew of Quaker pacifists, Albert Bigelow, George Willoughby, William R. Huntington, James Peck and Orion Sherwood had attempted to sail into this forbidden zone to protest nuclear testing and had been brought back by the U.S. Coast Guard.[11] The example set by the Golden Rule and her crew was also the inspiration for all the modern environmental and peace voyages, and craft that followed in her wake.[12]

Impressed by the reasoning and character of these men, Earle and Barbara joined the Society of Friends (Quakers) and considered taking over their protest in the Phoenix. Dr. Reynolds, an expert on the dangers of radiation, was concerned about the effect of this additional radiation on the world environment. Mikami, as a citizen of Hiroshima, said in effect that his desire to be included on such a trip was a "no brainer." The family spent days in research, thought and prayer and on June 11, 1958, the Phoenix cleared from Honolulu "for the high seas." On July 1, at the edge of the invisible perimeter of the zone, Reynolds announced by radiotelephone, on the international frequency for ships at sea, "The United States yacht Phoenix is sailing today into the nuclear test zone as a protest against nuclear testing..." The Phoenix became the first vessel to enter a nuclear test zone in protest when they sailed into the test area at Bikini Atoll. (Years later, in private correspondence, Captain Bigelow wrote Earle that most people had never heard of the Phoenix and thought the Golden Rule had sailed into the area.) They were intercepted 65 miles (105 km) inside the forbidden area by an American Coast Guard vessel, the Planetree, whose armed officers boarded the yacht and put Dr. Reynolds under arrest. They ordered him to sail the Phoenix to Kwajalein, escorted by the Navy destroyer Collett and from there they flew him, with Barbara and Jessica, back to Honolulu for trial.

Barbara returned to Kwajalein to help Ted (then age 20) and Mikami sail the Phoenix back to Honolulu, a trip of 60 days (August 15 – October 14) against the wind,[13] while Earle was being tried and convicted for entering the off-limits zone.[14][15] When Earle's conviction was overturned on appeal, the family sailed back to Hiroshima and Nick Mikami became the first Japanese yachtsman to sail around the world. The Phoenix was declared a Japanese national shrine, and city buses were re-routed past its dock so bus conductors could point it out to passengers.

Voyage to protest Soviet nuclear tests, 1961

In October 1961 the Reynolds family, now living back in Japan, sailed the Phoenix on a second protest voyage, this time to Nakhodka, USSR, to protest the resumption of Soviet nuclear resting. As the Japanese government would not give Mikami a passport to travel to the Soviet Union, American citizen Tom Yoneda sailed with them.[16][17] They were stopped within the 12-mile (19 km) limit claimed by the USSR by a Soviet Coast Guard boat. The captain and several other officers jumped aboard the Phoenix. Although the Reynoldses were able to have a two-hour discussion about peace with him, Captain Ivanov would not accept the hundreds of letters from Hiroshima and Nagasaki citizens, begging for peace.

Voyages to North Vietnam and China, 1967–1968

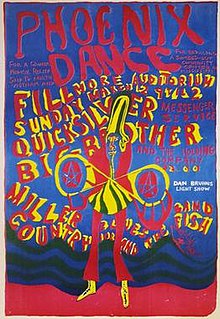

After Earle and Barbara divorced in 1964, Earle and his new wife Akie Nagami, a citizen of Hiroshima, sailed the Phoenix in 1967 through the American battle fleet to North Vietnam to deliver medical supplies to civilians injured by American bombing.[18] A fund raising concert/dance event was organized and held at the Fillmore Auditorium. The bands that played were Country Joe and the Fish, Big Brother and the Holding Company (with Janis Joplin), Steve Miller Blues Band, and Quicksilver Messenger Service. A multi-national crew delivered nearly a ton of medical aid to the Red Cross Society of North Vietnam for victims of the war. They spent eight days visiting hospitals in Hanoi and Haiphong and observing the effects of American bombing on outlying villages.[19] This journey was recorded in the documentary film Voyage of the Phoenix filmed by William Heick for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.[20]

They also attempted two goodwill missions to China "from a Japanese and an American" (at that time neither country recognized Red China) but were physically prevented from doing so, the first time (1967) by the Japanese government and the second (1968) by the Chinese Coast Guard.

Final Pacific crossing and retirement

For these attempts, the Japanese government expelled Reynolds in 1970 from the country in which he had lived for 13 years. He and Akie sailed the Phoenix to San Francisco and settled at Quaker Center in Ben Lomond, California, near Santa Cruz with the boat moored at nearby Moss Landing. During that time, after offering the Phoenix to each of his three grown children and after being turned down, Earle sold the Phoenix to another American family intending to sail around the world and gave the $20,000 from the sale to the Quaker Center in exchange for lifetime residency there.

In March 2007, mention of the Phoenix, gutted and minus both masts and its hand-carved Phoenix figurehead, showed up in an ad on Craigslist which began, "FREE: 50-foot yacht. . ." John Gardner of Lodi, California, then 31, took possession of the Phoenix and had it towed up the Sacramento River, hoping to restore it and use it to rehabilitate young people recovering from substance abuse. During the journey, the yacht collided with a dock and had to be kept afloat with the help of a battery-powered bilge pump.[21] In August 2010 the Phoenix went down off Tyler Island despite Gardner's efforts to keep it from sinking.[22] In September 2010 Dr. Naomi Reynolds, granddaughter of the original Dr. Reynolds, took possession of the yacht, resting in 25 feet of water in the Mokelumne River.[23] A diver inspected the vessel and found no serious damage.[24] Peace activists are currently restoring the Golden Rule (2013) and plan to resume peace activities in it. They hope to raise funds to raise and restore Phoenix of Hiroshima next.[25][26]

References

- ^ Reynolds, E. L. Growth and Development of Hiroshima Children Exposed to the Atomic Bomb. Three Year Study (1951–3). Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission Technical Report 20-59, 1959. Cited in Joseph L. Belsky and William J. Blot, Adult Stature in Relation to Childhood Exposure to the Atomic Bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- ^ Earle Reynolds, "We Crossed the Pacific the Hard Way," Saturday Evening Post, May 7, 14 and 21, 1955.

- ^ Sontag, Lester Warren and Reynolds, Earle L., "Ossification Sequences in Identical Triplets: A Longitudinal Study of Resemblances and Differences in the Ossification Patterns of a Set of Monozygotic Triplets." Journal of Heredity, 35 (2): 57–64. 1944.

- ^ Reynolds, 1955.

- ^ "Ecuador: Galapagos Pirates," Time Magazine, March 3, 1958.

- ^ Mildred and William Rhodes Hervey Jr., "The Yacht Valinda is taken over by 21 escaping prisoners," Life Magazine, March 10, 1958

- ^ "Hijacked by Escaping Convicts!"

- ^ Reynolds, Earle and Barbara, All in the Same Boat, New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1962

- ^ Reynolds, Jessica, Jessica's Journal, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1958. Eleven-year-old Jessica's diary account of the first year of the voyage around the world in the Phoenix.

- ^ Reynolds, Barbara Leonard, Cabin Boy and Extra Ballast, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1958. Fictional children's story of a family sailing from Japan to Hawaii., based on the Phoenix voyage.

- ^ Scott H. Bennett (2003). Radical Pacifism. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630036.

- ^ "Resurrecting the Golden Rule—Anti-Nuke Flagship," Latitude 38, March 2013, pp 100–104.

- ^ Barbara Reynolds, Upwind, unpublished.

- ^ Reynolds, Earle, The Forbidden Voyage, New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1961. Non-fiction.

- ^ Norman Cousins, "Earle Reynolds and His Phoenix," Saturday Review, 1958.

- ^ Reynolds, Jessica, To Russia with Love, Tokyo: Chas. E. Tuttle Co., (Japanese translation) 1962

- ^ Reynolds, Jessica, To Russia with Love, Wilmington, OH: Peace Resource Center, Wilmington College, due out in 2010.

- ^ "Quaker-sponsored American pacifists sail from Japan in yacht Phoenix of Hiroshima to bring medical supplies to North Vietnam," video clip.

- ^ Boardman, Elizabeth Jelinek, The Phoenix Trip: Notes on a Quaker Mission to Haiphong, Burnsville, N.C.: Celo Press, 1901 Hannah Branch Road, Burnsville, NC 28714 1985

- ^ Voyage of the Phoenix. Produced by Richard Faun; directed by William Heick for the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. Videocassette (56 min., 41 sec.); 1/2" VHS. UCSC McHenry Library Media Center, VT3693; UCSC Special Collections, VT3693 Santa Cruz.

- ^ "Lodi man working to turn historic ship into a vessel for second chances," March 24, 2007.

- ^ Michael Fitzgerald, "Pacifists' dream to recover Phoenix may be sunk," The Record, August 18, 2010.

- ^ "Phoenix of Hiroshima: Back in the Family," Aug 22, 2010.

- ^ Naomi Reynolds, "Open Letter to Friends of the Phoenix," Posted 4 September, 2010.

- ^ Salvage Efforts for the Phoenix

- ^ Peace Monuments Related to Boats or Ships

Bibliography

- Reynolds, Earle L., "We Crossed the Pacific the Hard Way," The Saturday Evening Post, May 7, 14 and 21, 1955.

- Reynolds, Jessica. Jessica's Journal. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1958.

- Reynolds, Ted. "Voyage of Protest." Scribble, Winter, 1959

- Bigelow, Albert. The Voyage of the Golden Rule: An Experiment with Truth. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company., Inc., 1959.

- Reynolds, Jessica. To Russia with Love (Japanese translation), Tokyo: Chas. E. Tuttle Co., 1962.

- Reynolds, Earle and Barbara. All in the Same Boat. New York: David McKay Co., Inc., 1962

- Reynolds, Earle. Forbidden Voyage. New York: David McKay Co., Inc., 1961

- Shaver, Jessica. "Seafaring memories of the South Seas," (Long Beach, CA) Press-Telegram, Feb. 2/3, 1983.

- Boardman, Elizabeth Jelinek (1985). The Phoenix Trip: Notes on a Quaker Mission to Haiphong. Burnsville, N.S.: Celo Press. ISBN 978-0-914064-22-0.

- Shaver, Jessica. "I Learned About Boating From This." Burgee, Feb., 1989.

- Shaver, Jessica Reynolds. "An Education I Wouldn't Trade," Home Education Magazine, May–June, 1991.

- Shaver, Jessica. "First Sail Brings First Sale," Byline, Feb., 1995.

- Reynolds, Jessica. To Russia with Love (English original). Wilmington, OH: Wilmington College, due out 2010.

External links

- Salvage efforts for the Phoenix

- Information on the Phoenix from Jessica Reynolds Shaver Renshaw

- Peace Monuments Related to Boats or Ships

- Wittner, Lawrence S., "The Long Voyage: The Golden Rule and Resistance to Nuclear Testing in Asia and the Pacific," The Asia-Pacific Journal, 8-3-10, February 22, 2010.

- Wittner, Lawrence S., PhD, "Preserving the Golden Rule as a Piece of Anti-Nuclear History," February 14, 2010, article about the Golden Rule and the Phoenix.

- 30-second newsreel footage on the voyage of the Phoenix to Haiphong in 1967.

- The Earle and Akie Reynolds Collection at the University of California at Santa Cruz has extensive writings by, photographs of and information about Dr. Earle Reynolds and his second wife.

- Peace Resource Center (Wilmington College, Wilmington, OH), founded by activist, author and peace educator Barbara Reynolds in August 1975 to house the largest collection (outside Japan) on materials related to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and to teach peace skills to new generations.

- College Peace Collection: Committee for Non-Violent Action Records, 1958–1968

- The Australian Broadcasting Corporation: Radio National's, Radio Eye, "Earle Reynolds and 'The Phoenix'"

- [1]

- Vietnam's Holy Week Ends on a Bloody Note: "A Tass dispatch from Hanoi said Dr. Earle L. Reynolds' ketch Phoenix carrying $10,000 worth of American Quaker medical supplies to North Vietnam, sailed around Red China's Hainan Island and entered the Gulf of Tonkin.

- "The Reynoldses," Sports Illustrated Vault, April 23, 1956.

- Effects of radiation from tests in the Marshall Islands which Dr. Reynolds protested and on the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon from American nuclear testing in 1954. One crew member of the ship died from the exposure.