South Jordan, Utah

South Jordan, Utah | |

|---|---|

South Jordan City Hall, March 2006 | |

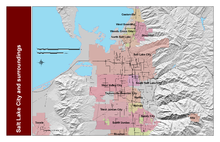

Location in Salt Lake County and the state of Utah. | |

| Coordinates: 40°33′42″N 111°57′39″W / 40.56167°N 111.96083°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Salt Lake |

| Established | 1859 |

| Incorporated | November 8, 1935[1] |

| Named for | Jordan River |

| Government | |

| • Type | council–manager |

| • Mayor | Dawn Ramsey |

| • Manager | Gary L. Whatcott |

| Area | |

• Total | 22.31 sq mi (57.77 km2) |

| • Land | 22.22 sq mi (57.54 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.23 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,439 ft (1,353 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 77,487 |

| • Density | 3,452.07/sq mi (1,332.86/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 84009, 84095 |

| Area code(s) | 385, 801 |

| FIPS code | 70850 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1432728[4] |

| Website | www |

South Jordan is a city in south central Salt Lake County, Utah, United States, 18 miles (29 km) south of Salt Lake City. Part of the Salt Lake City metropolitan area, the city lies in the Salt Lake Valley along the banks of the Jordan River between the 10,000-foot (3,000 m) Oquirrh Mountains and the 11,000-foot (3,400 m) Wasatch Mountains. The city has 3.5 miles (5.6 km) of the Jordan River Parkway that contains fishing ponds, trails, parks, and natural habitats. The Salt Lake County fair grounds and equestrian park, 67-acre (27 ha) Oquirrh Lake, and 37 public parks are located inside the city. As of 2020, there were 77,487 people in South Jordan.

Founded in 1859 by settlers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and historically an agrarian town, South Jordan has become a rapidly growing bedroom community of Salt Lake City. Kennecott Land, a land development company, has recently begun construction on the master-planned Daybreak Community for the entire western half of South Jordan, potentially doubling South Jordan's population. South Jordan was the first municipality in the world to have two temples of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Jordan River Utah Temple and Oquirrh Mountain Utah Temple), it now shares that distinction with Provo, Utah. The city has two TRAX light rail stops, as well as one commuter rail stop on the FrontRunner.

History

Pre-European

The first known inhabitants were members of the Desert Archaic Culture who were nomadic hunter-gatherers. From 400 A.D. to around 1350 A.D., the Fremont people settled into villages and farmed corn and squash.[5] Changes in climatic conditions to a cooler, drier period and the movement into the area of ancestors of the Ute, Paiute, and Shoshone, led to the disappearance of the Fremont people.[6] When European settlers arrived, there were no permanent Native American settlements in the Salt Lake Valley, but the area bordered several tribes – the territory of the Northwestern Shoshone to the north,[7] the Timpanogots band of the Utes to the south in Utah Valley,[8] and the Goshutes to the west in Tooele Valley.[9]

The only recorded trapper to lead a party through the area was Étienne Provost, a French Canadian. In October 1824, Provost's party was lured into an Indian camp somewhere along the Jordan River north of Utah Lake. The people responsible for the attack were planning revenge against Provost's party for an earlier unexplained incident involving other trappers. Provost escaped, but his men were caught off-guard and fifteen of them were killed.[10]

Early Latter-day Saint settlement

On July 22, 1847, an advanced party of the first Latter-day Saint pioneers entered the valley and immediately began to irrigate land and explore the area with a view to establishing new settlements.[11] Alexander Beckstead, a blacksmith from Ontario, Canada, moved his family to the West Jordan area in 1849, and became the first of his trade in the south Salt Lake Valley. He helped dig the first ditch to divert water from the Jordan River, powering Archibald Gardner's flour mill.[12] In 1859, Beckstead became the first settler of South Jordan by moving his family along the Jordan River where they lived in a dugout cut into the west bluffs above the river.[13] The flood plain of the Jordan was level, and could be cleared for farming if a ditch was constructed to divert river water along the base of the west bluff. Beckstead and others created the 2.5-mile (4.0 km) "Beckstead Ditch",[14] which is still in use for irrigation of city parks and Mulligan's golf course.[15]

In 1863, the South Jordan Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized as a branch of the West Jordan Ward, giving South Jordan its name.[16] The Branch consisted of just nine families. A school was built in 1864 out of adobe and also served as the Church Meetinghouse for the South Jordan Branch.[17] As South Jordan grew, a new and larger building was constructed in 1873 on the east side of the site of the present-day cemetery. It had an upper and lower entrance with a granite foundation using left-over materials brought from the granite quarry at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon. The upper story was made of oversized adobe bricks.[17] The main hall had curtains which could be pulled to section off the hall for classes. The meetinghouse also served as the "ward" school when it was held during the fall and winter months. It came to be known as the "Mud Temple", and was in use until 1908.[18]

In 1876, work was completed on the South Jordan Canal which took water out of the Jordan River in Bluffdale and brought it above the river bluffs for the first time.[13] As a result of the new canal, most of the families moved up away from the river onto the "flats" above the river which they could now irrigate. In 1881, the Utah and Salt Lake Canal was completed. It runs parallels to the west side of today's Redwood Road. With the completion of the canal system, greater acreage could be farmed, which led to the area's population increasing.[17]

Twentieth century

In the late 1890s, alfalfa hay was introduced and took the place of tougher native grasses which had been used up to that point for feed for livestock. In good years, alfalfa could produce three crops that were stored for winter. Sugar beets were introduced to South Jordan around 1910. Farmers liked sugar beets because they could be sold for cash at the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company factory in West Jordan.[19]

A big celebration was held on January 14, 1914, to commemorate the arrival of electrical power, the addition of a water tank and supply system for indoor pumping and a new park for South Jordan.[20] By the 1930s, the area needed a water tank to store water for residents living further west. The only way to get a federal grant was to incorporate and become a city.[21] Citizens voted to incorporate on November 8, 1935, and immediately issued bonds to obtain money for the water tank. The city was initially governed by a Town Board with responsibilities over parks, water and the cemetery. In 1978, the city moved to a mayor-council form of government and assumed local supervision of police, fire, road and building inspections from Salt Lake County.[22][23]

One of the worst school bus accidents in United States history occurred on December 1, 1938. A bus loaded with 38 students from South Jordan, Riverton, and Bluffdale crossed in front of an oncoming train that was obscured by fog and snow. The bus was broadsided killing the bus driver and 23 students.[24][25] The concern about bus safety from the South Jordan accident led to changes in state and eventually federal law mandating that buses stop and open the doors before proceeding into a railroad crossing.[26] The same railroad crossing was the site of many other crashes in the following years with the last deadly crash occurring on December 31, 1995, when three teens died while crossing the tracks in their car.[27] The crossing was finally closed, but not until crashes occurred in 1997[28] and 2002.[29]

In 1950, Salt Lake County had 489,000 acres (198,000 ha) devoted to farming.[30] But by 1992, due to increasing population, land devoted to farming had decreased to 108,000 acres (44,000 ha).[31] As a result of this urbanization, South Jordan's economy went from agrarian to being a bedroom community of Salt Lake City. Kennecott Land began a development in 2004 called Daybreak, which is a 4,200-acre (1,700 ha) planned community that will contain more than 20,000 homes and includes commercial and retail space.[32] In 2022, the remaining 1,300-acre (530 ha) undeveloped land was sold to Larry H. Miller Group.[33] In 1981, the Jordan River Utah Temple was completed. In 2009, the Oquirrh Mountain Utah Temple was completed and became the second temple to be built in South Jordan. South Jordan was the first city in the world to have two temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, namely the Oquirrh Mountain Utah Temple and the Jordan River Utah Temple. The second city to carry that distinction is Provo, Utah, about 30 miles to the south of South Jordan.[34] In May 2003 the Sri Ganesha Hindu Temple was completed.[35]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 22.22 square miles (58 km2), of which 0.09 square miles (0.23 km2), 0.4 percent, is water.[2]

The relative flatness of South Jordan is due to lacustrine sediments of a pleistocene lake called Lake Bonneville. Lake Bonneville existed from 75,000 to 8,000 years ago; at its peak some 30,000 years ago, the lake reached an elevation of 5,200 feet (1,600 m) above sea level and had a surface area of 19,800 square miles (51,000 km2).[36] The elevation of South Jordan ranges from approximately 4,300 feet (1,300 m) near the Jordan River in the east and rises gently to the foothills of the Oquirrh Mountains at 5,200 feet (1,600 m).[37]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 869 | — | |

| 1950 | 1,048 | 20.6% | |

| 1960 | 1,354 | 29.2% | |

| 1970 | 2,942 | 117.3% | |

| 1980 | 7,492 | 154.7% | |

| 1990 | 12,220 | 63.1% | |

| 2000 | 29,437 | 140.9% | |

| 2010 | 50,418 | 71.3% | |

| 2020 | 77,487 | 53.7% | |

| Population 2010 and 2020[3] | |||

According to estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau,[3] as of 2020, there were 77,487 people in South Jordan. The racial makeup of the city was 84.7% non-Hispanic White, 1.0% Black, 0.2% Native American, 3.8% Asian, 0.8% Pacific Islander, and 2.6% from two or more races. 7.1% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the 2010 census, there were 50,418 people residing in 14,333 households. The population density was 2,278 people per square mile (880/km2). There were 14,943 housing units at an average density of 675.3 per square mile (260.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.5% White, 0.2% African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.6% Asian, 0.9% Pacific Islander, and 2.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.0% of the population. The racial makeup of Salt Lake County was 81.2% White, 1.6% African American, 0.9% Native American, 3.1% Asian, 1.4% Pacific Islander, and 1.9% from two or more races. Hispanic of any race was 16.4%. The racial makeup of Utah was 92.9% White, 1.3% African American, 1.4% Native American, 3.3% Asian, 1.5% Pacific Islander, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanic of any race was 13%.[38][39]

There were 14,433 households, out of which 46.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 76.5% were married couples living together, 6.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 14.1% were non-families. 11.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.83 compared to 2.94 for Salt Lake County and 3.03 for Utah.[38][39]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 37.8% under the age of 20, 6.0% from 20 to 24, 25.3% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 7.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.3 males.[38]

The median income for a household in the city was $104,597,[3] Salt Lake County was $74,865 and Utah was $71,621. Males had a median income of $65,722 versus $41,171 for females. The per capita income for the city was $39,453.[3] About 1.6% of families and 2.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.7% of those under age 18 and 2.4% of those age 65 or over. In Salt Lake County, 9.0% of the population were below the poverty line and 8.9% of the population in Utah was below the poverty line. Of those people 25 years and older in the city, 97.1% were high school graduates compared to 90.8% in Salt Lake County and 87.5% in Utah. Those over 25 with a Bachelor's degree or higher weas 42.2%[3] of South Jordan's population.

There were 22,368 people employed over the age of 16 with 17,258 people working in the private sector, 2,744 in the government sector, 1,186 self-employed and 32 unpaid family workers. The mean travel time to work was 23.8 minutes. There were 4,153 people employed in educational services, health care and social assistance. There were 2,862 people employed in professional, scientific, management, administrative and waste management services. There were 2,420 people employed in finance, insurance, real estate and rental and leasing. There were 2,316 people employed in retail trade, 1,633 in construction and 2,050 in manufacturing.[40]

Crime

For the year 2019, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reported the city had 73 violent crimes reported to law enforcement, up from 27 in 2010; there were also 1,124 reports of property crimes, up from 1,050 in 2010.[41][42] The violent crime rate was 94 per 100,000 people compared to a national average of 379 and 236 for Utah. The property crime rate was 1,148 per 100,000 compared to a national rate of 2,110 and 1,682 for the State.[41][43] The FBI defines violent offenses to include forcible rape, robbery, murder, non-negligent manslaughter, and aggravated assault. Property crimes are defined to include arson, motor vehicle theft, larceny, and burglary.[44]

For the year 2020, statistics published by the Utah Department of Public Safety's Bureau of Criminal Identification showed South Jordan had a total of 60 police officers for a rate of .75 officers per 1,000 residents. City police made a total of 998 arrests, up from 910 in 2010. Total crimes reported were 3,338, up from 2,096 crimes in 2010. Total crimes contain categories that include everything from murder, rape and assault to disorderly conduct and DUI. The index crime rate per 1,000 people was 19.17, down from 21.42 in 2010.[45][46]

Parks and recreation

The city has 35 municipal parks and playgrounds that includes areas for baseball, softball, football, soccer, and lacrosse, volleyball, pickleball, tennis and skateboarding. Other recreational facilities owned by South Jordan City include the Aquatic and Fitness center, Community Center providing the senior programs, three fishing ponds stocked with rainbow trout and catfish by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, and Mulligan's two miniature golf and two nine-hole executive golf courses.[47]

Salt Lake County operates two regional parks inside the city. The 120-acre (49 ha) Equestrian Park that sits adjacent to South Jordan City Park. The park grounds contain a horse racing track, a polo and dressage field, indoor arenas and stables.[48] The Salt Lake County Fair is held every August at the park. The 65-acre (26 ha) Bingham Creek Regional Park includes multi-purpose sport fields, a destination playground, a disc golf course, and biking and other multi-use trails along the creek. A 90-acre (36 ha) addition is in the planning stages that will include areas for BMX, basketball, pickleball, tennis and volleyball.[49]

The 67-acre (27 ha) Oquirrh Lake sits inside 137 acres (55 ha) of park and wetlands located at the Daybreak Community. Recreational opportunities include fishing, sail boating, kayaking and canoeing. The lake has been stocked with trout, bigmouth bass, channel catfish, and bluegill.[50] In addition to the lake, the Daybreak community includes 22 miles (35 km) of trails, 37 parks and five swimming pools.[51] The lake, parks and pools are privately owned by Daybreak's home owners association and are for residents only.[50]

Privately owned, but open to the public, Glenmoor Golf course is inside city limits.[52] Salt Lake County-owned Mountain View Golf Course is 0.3 miles (0.48 km) north in West Jordan[53] and Sandy-owned River Oaks Golf Course borders the Jordan River.[54]

Government

South Jordan has a six-member council form of government.[55] The council, the city's legislative body, consists of five members and a mayor, each serving a four-year term. The council sets policy, and the city manager oversees day-to-day operations. As of 2022[update], the mayor is Dawn R. Ramsey. The city council meets the first and third Tuesdays of each month at 6:30 pm.[56]

Utah is one of the country's most Republican states[57] and South Jordan follows Utah's trend with only Republican state and federal elected officials. South Jordan is part of Utah's 4th congressional district of the United States House of Representatives. For the state government between 2023 and 2033, the city is part of Utah Senate's 17th district, and parts of the 39th, 44th, 45th, 46th and 48th districts in the Utah House of Representatives.[58]

Education

South Jordan lies within Jordan School District. The district has seven elementary schools (Daybreak, Eastlake, Elk Meadows, Golden Fields, Jordan Ridge, Monte Vista, and South Jordan Elementaries), three middle schools (South Jordan and Elk Ridge, and Mountain Creek) and two high schools (Bingham High School and Herriman High School) serving the students of South Jordan.[59] In addition, there is Paradigm public charter high school, Early Light Academy and Hawthorne Academy public charter elementaries and two private schools (American Heritage and Stillwater Academy).

Roseman University of Health Sciences, a private university, houses schools of pharmacy, dentistry, and nursing.[60]

Transportation

Interstate 15, a twelve-lane freeway, is located on the eastern edge of the city and provides two interchanges inside city limits at 10600 South and 11400 South. Bangerter Highway (State Route 154), a six-lane expressway, traverses the center of the city with interchanges at 9800 South, 10400 South and 11400 South. The Mountain View Corridor, an eventual ten-lane freeway, is located on the western edge of the Daybreak Community.[61]

South Jordan is served by the Utah Transit Authority (UTA) bus system and UTA's TRAX light rail Red Line.[62] The Red Line connects the TRAX line running to downtown Salt Lake City and the University of Utah. Two TRAX stations, with park and ride lots, are located inside the Daybreak Community. The South Jordan Parkway Station is located at approximately 10600 South and has 400 shared park and ride spaces. The Daybreak Parkway Station is located at 11400 South and has 600 park and ride spaces. Two other stations are located inside West Jordan at the city boundary with South Jordan, the 5600 West Old Bingham Highway Station and the 4800 West Old Bingham Highway Station.[63] The travel time between the Daybreak Parkway Station to downtown Salt Lake City is approximately 60 minutes.[64]

UTA's FrontRunner commuter rail system has a station at South Jordan's eastern edge at 10200 South. The FrontRunner extends north to Ogden and south to Provo.[65]

Infrastructure

Electric service to South Jordan residents is provided by Rocky Mountain Power. Natural gas service is provided by Questar. High-speed internet connections are provided by Comcast, Qwest and Google.

South Jordan city owns the water distribution system. Drinking water is provided by Jordan Valley Water Conservancy District. Secondary water, a non-potable water used for landscaping, is provided from the canals running through the city.[15] South Valley Sewer District operates the sewer system. South Jordan City contracts out to Ace Recycling and Disposal for curbside pickup of household garbage and recycling.[66]

University of Utah and Veterans Affairs operate large clinics in the city.

Economy

According to South Jordan's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the principal employers in the city are:[67]

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Merit Medical | 2,086 |

| 2 | Jordan School District | 1,663 |

| 3 | Ultradent | 1,502 |

| 4 | Willis Towers Watson | 1,000 |

| 5 | Walmart | 760 |

| 6 | AdvancedMD | 655 |

| 7 | City of South Jordan | 502 |

| 8 | Intermountain Healthcare | 480 |

| 9 | OOCL | 475 |

| 10 | Physician's Group of Utah (Steward Health Care System) |

453 |

Notable people

- Edward J. Fraughton - (b. 1939), is an American artist, sculptor, and inventor.

- Harvey Langi - (b. 1992), is an NFL linebacker for the Denver Broncos.

- Star Lotulelei - (b. 1989), is a Tongan NFL defensive tackle who played for the Buffalo Bills.

- Dax Milne - (b. 1999), is an NFL wide receiver and return specialist for the Washington Commanders.

- Apolo Ohno - (b. 1982) is a retired Winter Olympics short track speed skating competitor and member of the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame (inducted 2019).

- Denise Parker - (b. 1973) is an American Olympics archer who was a member of the American squad.

See also

References

- ^ "Media Relations". South Jordan City. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ a b "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: South Jordan city, Utah". US Census. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Madsen, David B. (1994), "The Fremont", in Powell, Allan Kent (ed.), Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0874804256, OCLC 30473917, archived from the original on November 1, 2013, retrieved October 31, 2013

- ^ Madsen 2002, pp. 13–14

- ^ Madsen 1985, pp. 6–7

- ^ Janetski 1991, pp. 32–33

- ^ Cuch 2000, p. 75

- ^ Alter, Cecil (1941). "Journal of W.A. Ferris 1830–1835". Utah Historical Quarterly. 9: 105–106. doi:10.2307/45057569. JSTOR 45057569.

- ^ "Mormon Settlement". Utah History to Go. Utah State Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Bateman 1998, p. 7

- ^ a b Bateman 1994, p. 513

- ^ Bateman 1998, p. 8

- ^ a b "Water Services". South Jordan City. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Jensen, Andrew, ed. (1941). "South Jordan Ward". Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing Company. p. 816. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Andrew (1889). "South Jordan Ward". The Historical Record: A Monthly Periodical, Devoted Exclusively to Historical, Biographical, Chronological and Statistical Matters. 5: 335. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ Bateman 1998, p. 153

- ^ Bateman 1998, p. 24

- ^ "Big Celebration at South Jordan". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. January 17, 1914.

- ^ "Community Profile: South Jordan". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. August 26, 1991. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "South Jordan in transition period". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. September 27, 1978. p. S7. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Riverton police chief want to keep out of politics". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. August 9, 1978. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "Casualty Toll in Bus Tragedy Mounts to 24". Pittsburgh Press. December 2, 1938. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- ^ "New Crash Death Boosts Bus-Train Fatalities To 23". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. December 2, 1938. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- ^ "Bus crash in 1938 led to train laws". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. October 20, 2009. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- ^ "New Year's Wrecks Kill Six, Including 3 in Train Collision". Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City. January 2, 2006.

- ^ "S. Jordan driver walks away from train wreck". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. July 29, 1997. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ "Man critical after truck-train crash". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. January 15, 2002. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Statistics for Counties" (PDF). 1950 Census of Agriculture. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ "County Summary Highlights: 1992" (PDF). 1992 Census of Agriculture. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ "Bench mark: Mogul of Daybreak aims to shape western Salt Lake Valley's future". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. August 22, 2009. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Larry H. Miller's real estate arm makes big move, buys booming Daybreak in South Jordan". Salt Lake Tribune. April 12, 2022. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Oquirrh Mountain Utah Temple". Temples. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- ^ [cite web | url=//www.utahganeshatemple.org/mission | completed

- ^ Brimhall, Willis H.; Merritt, Lavere B. (1981). "Geology of Utah Lake: Implications for Resource Management". Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs (5: Utah Lake Monograph): 25–27. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ "Virtual Utah". Utah State. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c "South Jordan City Demographics". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet for Salt Lake County". U.S. Census Bureau. January 24, 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "Fact Sheet for South Jordan, Economic Characteristics". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ a b "Utah Offenses Known to Law Enforcement". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Utah Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by State by City, 2010". Federal Bureau of Investigation. September 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "Crime in the United States by Region, Geographic Division, and State, 2018–2019". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Offenses Known to Law Enforcement". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "2020 Crime in Utah Report" (PDF). Bureau of Criminal Identification. pp. 56, 74, 126. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "2010 Crime in Utah Report" (PDF). Bureau of Criminal Identification. pp. 20, 69. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Parks". South Jordan City. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Salt Lake County Equestrian Park". Visit Salt Lake. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Bingham Creek Regional Park". South Jordan City. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions". Daybreak. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Parks". Daybreak. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Glenmoor Golf Course". Glenmoore Golf Course. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Mountain View Golf Course". Salt Lake County. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "River Oaks Golf Course". Sandy City. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "City Manager". South Jordan Website. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ "South Jordan City". South Jordan City Council. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "State of the States: Political Party Affiliation". Gallup. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ "Utah State Legislative District Maps". Utah State Legislature. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Boundaries, Maps & Bus Stops". Jordan School District. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "Roseman University in Utah". Roseman University. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "Mountain View Corridor". Utah Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Overview". Mid-Jordan TRAX Line. Utah Transit Authority. February 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Mid-Jordan Transit Corridor Project Information" (PDF). Utah Transit Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Overview". Utah Transit Authority. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive look at FrontRunner South rail through Jordan Narrows". ksl.com. Salt Lake City: Deseret Digital Media. March 2, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Sanitation Services - Garbage". South Jordan City. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). South Jordan City. January 19, 2021. p. 152. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

Bibliography

- Bateman, Ronald R. (1994), "South Jordan", in Powell, Allan Kent (ed.), Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0874804256, OCLC 30473917, archived from the original on January 13, 2017, retrieved October 31, 2013

- Bateman, Ronald R. (1998). Of Dugouts and Spires: The History of South Jordan, Utah. South Jordan City Corporation.

- Cuch, Forrest S., ed. (2000). A History of Utah's American Indians. Logan: Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-0-913738-48-1. Archived from the original on June 21, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- Janetski, Joel C (1991). The Ute of Utah Lake. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-343-3.

- Madsen, Brigham D. (1985). The Shoshoni Frontier and the Bear River Massacre. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-494-2.

- Madsen, David B. (2002). Exploring the Fremont. Salt Lake City: Utah Museum Natural History. ISBN 978-0-940378-35-3.

External links