Sweden Finns

ruotsinsuomalaiset

sverigefinnar | |

|---|---|

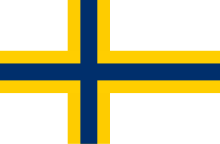

Flag of the Sweden Finns | |

| Total population | |

| estimated c. 426,000–712,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Stockholm | 46,927[1] |

| Gothenburg | 20,372 |

| Eskilstuna | 12,072 |

| Västerås | 11,592 |

| Södertälje | 10,722 |

| Borås | 9,821 |

| Uppsala | 8,838 |

| Botkyrka Municipality | 8,408 |

| Huddinge Municipality | 7,729 |

| Haninge Municipality | 7,015 |

| Languages | |

| Finnish (Sweden Finnish) and Swedish | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Finns | |

Sweden Finns (Finnish: ruotsinsuomalaiset; Swedish: sverigefinnar) are a Finnish-speaking national minority in Sweden.[2]

People with Finnish heritage comprise a relatively large share of the population of Sweden. In addition to a smaller part of Sweden Finns historically residing in Sweden, there were about 426,000 people in Sweden (4.46% of the total population in 2012) who were either born in Finland or had at least one parent who was born in Finland.[3] In 2017 that number was 720,000.[4] Like the Swedish language, the Finnish language has been spoken on both sides of the Gulf of Bothnia since the late Middle Ages. Following military campaigns in Finland by Sweden in the 13th century, Finland gradually came under Swedish rule and Finns in Finland and Sweden became subjugates of Sweden. Already in the 1400s, a sizeable population of Stockholm spoke Finnish, and around 4% in the 1700s.[5] Finland remained a part of Sweden until 1809 when the peace after the Finnish War handed Finland to the Russian Empire, leaving Finnish populations on the Swedish side of the Torne river.

In the 1940s, 70,000 young Finnish children were evacuated from Finland. Most of them came to Sweden during the Winter War and the Continuation War, and around 20% remained after the war. Helped by the Nordic Passport Union, Finnish immigration to Sweden was considerable during the 1950s and 1960s. In 2015, 156 045 people in Sweden (or 1.58% of the Swedish population) were Finnish immigrants.[6] Not all of them, however, were Finnish speakers.

The national minority of Sweden Finns usually does not include immigrated Swedish-speaking Finns, and the national minority of Sweden Finns is protected by Swedish laws that grant specific rights to speakers of the Finnish language. English somewhat lacks the distinction between Finns in Sweden (Swedish: sverigefinländare), which emphases nationality rather than linguistic or ethnic belonging and thereby includes all Finnish heritage regardless of language, and Sweden Finns (Swedish: sverigefinnar) which emphases linguistic and ethnic belonging rather than nationality and usually excludes Swedish-speaking Finns. Such distinctions are, however, blurred by the dynamics of migration, bilingualism, and national identities in the two countries. Speakers of Meänkieli are singled out as a separate linguistic minority by Swedish authorities.[7]

History

Communities of Finns in Sweden can be traced back to the Reformation when the Finnish Church in Stockholm was founded in 1533, although earlier migration, and migration to other cities in present-day Sweden, remain undisputed. (Strictly speaking this was not a case of emigration/immigration but of "internal migration" within pre-1809 Sweden.)

In the 16th and the 17th century large groups of Savonians moved from Finland to Dalecarlia, Bergslagen and other provinces where their slash and burn cultivation was suitable. This was part of an effort of the Swedish king Gustav Vasa, and his successors, to expand agriculture to these uninhabited parts of the country which were later on known as finnskogar ("Forests of the Finns").

In the 1600s, there were plans to set up a new region Järle län that would have contained most of the Forest Finns. In Sweden at this time, all legislation and official journals were also published in Finnish.[citation needed] Bank-notes were issued in Swedish and Finnish etc. After 1809, and the loss of the eastern part of Sweden (Finland) to Russia, the Swedish church planned a Finnish-speaking bishopric with Filipstad as seat. However, after the mid-1800s cultural imperialism and nationalism led to new policies of assimilation and Swedification of the Finnish-speaking population. These efforts peaked from the end of the 1800s and until the 1950s. Finnish speakers remain only along the border with Finland in the far North, and as domestic migrants due to unemployment in the North. Depending on definition they are reported to number to 30,000–90,000 — that is up to 1% of Sweden's population, but the proportion of active Finnish-speakers among them has declined drastically in the last generations, and Finnish is hardly spoken among the youngsters today. Since the 1970s largely unsuccessful efforts have been made to reverse some of the effects of Swedification, notably education and public broadcasts in Finnish, to raise the status of Finnish. As a result, a written standard of the local dialect Meänkieli has been established and taught, which has given reason to critical remarks from Finland, along the line that standard Finnish would be of more use for the students.

Distribution of Sweden Finns

The city of Eskilstuna, Södermanland, is one of the most heavily populated Sweden Finnish cities of Sweden, due to migration from Finland, during the 1950s until the 1970s, due to Eskilstuna's large number of industries. In Eskilstuna, the Finnish-speaking minority have both a private school (the only one in the city of Eskilstuna, there is no public school or teachers in Finnish at the public schools. Only the lower level is in Finnish, upper level is in Swedish) and only one magazine in Finnish. Some of the municipal administration is also available in Finnish.

In the Finnish mindset, the term "Sweden Finns" (ruotsinsuomalaiset) is first and foremost directed at these immigrants and their offspring, who at the end of the 20th century numbered almost 200,000 first-generation immigrants, and about 250,000 second-generation immigrants. Of these some 200,000–250,000 are estimated to be able to speak Finnish,[8] and 100,000 remain citizens of Finland. This usage is not quite embraced in Sweden. According to the latest research by SR's Finnish language channel Sveriges Radio Finska (formerly known as Sisuradio), there are almost 470,000 people who speak or understand Finnish or Meänkieli,[9] which was about 4.5% of the population of Sweden in 2019.

In the Swedish mindset, the term "Sweden Finns" historically denominated primarily the (previously) un-assimilated indigenous minority of ethnic Finns who ended up on the Swedish side of the border when Sweden was partitioned in 1809, after the Finnish War, and the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland was created. These Finnish-speakers are chiefly categorized as either Tornedalians originating at the Finnish–Swedish border in the far north, or Forest Finns (skogsfinnar) along the Norwegian–Swedish border in Central Sweden.

Today

Today Finnish is an official minority language of Sweden. The benefits of being a "minority language" are however limited to Finnish-speakers being able to use Finnish for some communication with local and regional authorities in a small number of communities (Borås, Borlänge, Botkyrka, Degerfors, Enköping, Eskilstuna, Fagersta, Finspång, Gällivare, Gävle, Göteborg, Gislaved, Hällefors, Håbo, Hallstahammar, Haninge, Haparanda, Hofors, Huddinge, Järfälla, Köping, Kalix, Karlskoga, Kiruna, Lindesberg, Ludvika, Luleå, Malmö, Mariestad, Motala, Norrköping, Nykvarn, Olofström, Oxelösund, Pajala, Söderhamn, Södertälje, Sandviken, Sigtuna, Skövde, Skellefteå, Skinnskatteberg, Smedjebacken, Solna, Stockholm, Sundbyberg, Sundsvall, Surahammar, Tierp, Trelleborg, Trollhättan, Trosa, Uddevalla, Umeå, Upplands-Väsby, Uppsala, Västerås, Norrtälje, Upplands-Bro, Älvkarleby, Örebro, Örnsköldsvik, Österåker, Östhammar, Övertorneå) where Finnish immigrants make up a considerable share of the population, but not in the rest of Sweden.[10][11]

Notable Sweden Finns

- Sebastian Aho, hockey player

- Anneli Alhanko, actress

- Hasse Aro, television host

- Miriam Bryant, singer

- Mikael Damberg, politician

- Markus Fagervall, singer and winner of Swedish Idol 2006

- Mika Hannula, former ice hockey player

- Elsa Hosk, professional model

- Peter Hultqvist, politician

- Jan Huokko, former ice hockey player

- Richard Jomshof, politician

- Johanna Jussinniemi, adult model

- Markus Krunegård, singer

- Marko Lehtosalo, singer and comedian

- Markus Mustonen, musician

- Mikael Niemi, author

- Martin Ponsiluoma, biathlete

- Sebastian Rajalakso, football player

- Mattias Ritola, ice hockey player

- Hanna Ryd, singer

- Timo Räisänen, musician

- Max Salminen, sailor

- Rami Shaaban, former football player

- Sami Sirviö, musician

- Daniel Ståhl, athlete

- Hans Tikkanen, chess player

- Ola Toivonen, football player

- Fredrik Virtanen, journalist

- Mika Zibanejad, ice hockey player

See also

- Sweden Finns' Day

- Languages of Sweden

- Sami

- Karelians

- Tornedalians

- Ingrians

- Forest Finns

- Finland-Swedes

- Kvens

References

- ^ "Ruotsinsuomalaiset". Archived from the original on 19 December 2007.

- ^ "Ds 2001:10 Mänskliga rättigheter i Sverige". The Government of Sweden. p. 20. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Fler med finsk bakgrund i Sverige". Sveriges Radio. Sverige Radio. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Vuonokari, Kaisa; Laitinen, Merja; Karlsson, Veronica (24 February 2017). "Ruotsissa on nyt 719 000 suomalaistaustaista". Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023 – via sverigesradio.se.

- ^ "SOU 2005:40 Rätten till mitt språk (del 2)" (in Swedish). SOU 2005:40. pp. 217–218. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Finland och Irak de två vanligaste födelsälnderna". Statistics Sweden. 2005. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Nationella minoriteter". The Government of Sweden. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Finska språket i Sverige". minoritet.se. Sámi Parliament of Sweden. 10 March 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Kuuntelijat – Lyssnarna Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish and Swedish) Sveriges Radio

- ^ Lag (2009:724) om nationella minoriteter och minoritetsspråk Archived 10 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Swedish law on national minorities and minority languages (in Swedish). Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Förvaltningsområdet för finska Archived 10 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. List of municipalities in the administrative area for the Finnish language, including municipalities added subsequently. Retrieved 31 May 2018.